Chapter 8. Learning

Operant Conditioning

Dinesh Ramoo

Approximate reading time: 45 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define operant conditioning

- Explain the difference between reinforcement and punishment

- Distinguish between reinforcement schedules

- Define insight and latent learning

The previous section of this chapter focused on the type of associative learning known as classical conditioning. Remember that in classical conditioning, something in the environment triggers a reflex automatically, and researchers train the organism to react to a different stimulus. Now we turn to the second type of associative learning, operant conditioning. In operant conditioning, organisms learn to associate a behaviour and its consequence (Table LE.1). A pleasant consequence makes that behaviour more likely to be repeated in the future. For example, Spirit, a dolphin at the National Aquarium in Baltimore, does a flip in the air when Spirit’s trainer blows a whistle. The consequence is that Spirit gets a fish.

| Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning | |

|---|---|---|

| Conditioning approach | An unconditioned stimulus (such as food) is paired with a neutral stimulus (such as a bell). The neutral stimulus eventually becomes the conditioned stimulus, which brings about the conditioned response (salivation). | The target behaviour is followed by reinforcement or punishment to either strengthen or weaken it, so that the learner is more likely to exhibit the desired behaviour in the future. |

| Stimulus timing | The stimulus occurs immediately before the response. | The stimulus (either reinforcement or punishment) occurs soon after the response. |

Psychologist B. F. Skinner saw that classical conditioning is limited to existing behaviours that are reflexively elicited, and it doesn’t account for new behaviours such as riding a bike. He proposed a theory about how such behaviours come about. Skinner believed that behaviour is motivated by the consequences we receive for the behaviour: the reinforcements and punishments. His idea that learning is the result of consequences is based on the law of effect, which was first proposed by psychologist Edward Thorndike. He worked with puzzle boxes within which he put street cats. The cats were incentivised to escape the boxes with food incentives. However, in order to escape the boxes, the cats had to do a series of moves like pulling a level and touching a button. Thorndike found that behaviours that led to escape increased with time but the cats did not get an insight that led to repeating the behaviours without errors (the number of errors just went down with each repetition). Thorndike called this the Law of Effect. According to the law of effect, behaviours that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviours that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated (Thorndike, 1911). Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about a desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again. An example of the law of effect is in employment. One of the reasons (and often the main reason) we show up for work is because we get paid to do so. If we stop getting paid, we will likely stop showing up—even if we love our job.

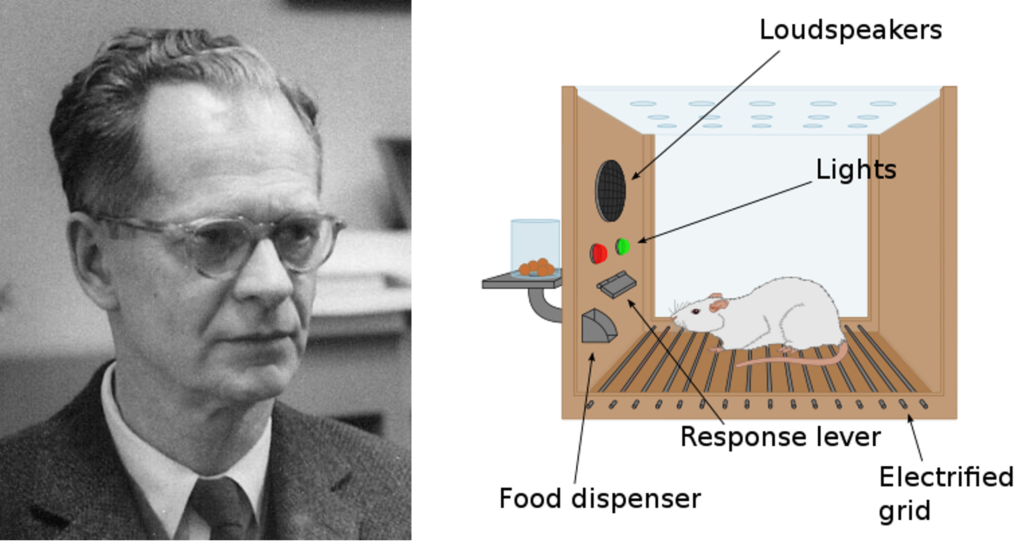

Working with Thorndike’s law of effect as his foundation, Skinner began conducting scientific experiments on animals (mainly rats and pigeons) to determine how organisms learn through operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938). He placed these animals inside an operant conditioning chamber, which has come to be known as a “Skinner box” (Figure LE.10). A Skinner box contains a lever (for rats) or disk (for pigeons) that the animal can press or peck for a food reward via the dispenser. Speakers and lights can be associated with certain behaviours. A recorder counts the number of responses made by the animal.

In discussing operant conditioning, we use several everyday words—positive, negative, reinforcement, and punishment—in a specialised manner. In operant conditioning, positive and negative do not mean good and bad. Instead, positive means you are adding something, and negative means you are taking something away. Reinforcement means you are increasing a behaviour, and punishment means you are decreasing a behaviour. Reinforcement can be positive or negative, and punishment can also be positive or negative. All reinforcers (positive or negative) increase the likelihood of a behavioural response. All punishers (positive or negative) decrease the likelihood of a behavioural response. Now let’s combine these four terms: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment (Table LE.2).

| Reinforcement | Punishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Something is added to increase the likelihood of a behaviour. | Something is added to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour. |

| Negative | Something is removed to increase the likelihood of a behaviour. | Something is removed to decrease the likelihood of a behaviour. |

Reinforcement

The most effective way to teach a person or animal a new behaviour is with positive reinforcement. In positive reinforcement, a desirable stimulus is added to increase a behaviour.

For example, you tell your five-year-old child, Karson, that if they clean their room, they will get a toy. Karson quickly cleans their room because they want a new art set. Let’s pause for a moment. Some people might say, “Why should I reward my child for doing what is expected?” But in fact we are constantly and consistently rewarded in our lives. Our pay cheques are rewards, as are high grades and acceptance into our preferred school. Being praised for doing a good job and for passing a driver’s test is also a reward. Positive reinforcement as a learning tool is extremely effective. It has been found that one of the most effective ways to increase achievement in school districts with below-average reading scores was to pay the children to read. Specifically, second-grade students in Dallas were paid $2 each time they read a book and passed a short quiz about the book. The result was a significant increase in reading comprehension (Fryer, 2010). What do you think about this program? If Skinner were alive today, he would probably think this was a great idea. He was a strong proponent of using operant conditioning principles to influence students’ behaviour at school. In fact, in addition to the Skinner box, he also invented what he called a teaching machine that was designed to reward small steps in learning (Skinner, 1961)—an early forerunner of computer-assisted learning. His teaching machine tested students’ knowledge as they worked through various school subjects. If students answered questions correctly, they received immediate positive reinforcement and could continue; if they answered incorrectly, they did not receive any reinforcement. The idea was that students would spend additional time studying the material to increase their chance of being reinforced the next time (Skinner, 1961).

In negative reinforcement, an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behaviour. For example, car manufacturers use the principles of negative reinforcement in their seatbelt systems, which go “beep, beep, beep” until you fasten your seatbelt. The annoying sound stops when you exhibit the desired behaviour, increasing the likelihood that you will buckle up in the future. Negative reinforcement is also used frequently in horse training. Riders apply pressure—by pulling the reins or squeezing their legs—and then remove the pressure when the horse performs the desired behaviour, such as turning or speeding up. The pressure is the negative stimulus that the horse wants to remove.

Punishment

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms. Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behaviour. In contrast, punishment always decreases a behaviour. In positive punishment, you add an undesirable stimulus to decrease a behaviour. An example of positive punishment is scolding a student to get the student to stop texting in class. In this case, a stimulus (the reprimand) is added in order to decrease the behaviour (texting in class). In negative punishment, you remove a pleasant stimulus to decrease behaviour. For example, when a child misbehaves, a parent can take away a favourite toy. In this case, a stimulus (the toy) is removed in order to decrease the behaviour.

Punishment, especially when it is immediate, is one way to decrease undesirable behaviour. For example, imagine that your four-year-old, Sasha, hit another child. You have Sasha write 100 times “I will not hit other children” (positive punishment). Chances are Sasha won’t repeat this behaviour. While strategies like this are common today, in the past children were often subject to physical punishment, such as spanking. It’s important to be aware of some of the drawbacks in using physical punishment on children. First, punishment may teach fear. Sasha may become fearful of the street, but Sasha also may become fearful of the person who delivered the punishment—you, the parent. Similarly, children who are punished by teachers may come to fear the teacher and try to avoid school (Gershoff et al., 2010). Consequently, most schools in the United States have banned corporal punishment. Second, punishment may cause children to become more aggressive and prone to antisocial behaviour and delinquency (Gershoff, 2002). They see their parents resort to spanking when they become angry and frustrated, so, in turn, they may act out this same behaviour when they become angry and frustrated. For example, because you spank Sasha when you are angry with them for misbehaving, Sasha might start hitting their friends when they won’t share their toys.

While positive punishment can be effective in some cases, Skinner suggested that the use of punishment should be weighed against the possible negative effects. Today’s psychologists and parenting experts favour reinforcement over punishment—they recommend that you catch your child doing something good and reward them for it.

Shaping

In his operant conditioning experiments, Skinner often used an approach called shaping. Instead of rewarding only the target behaviour, in shaping, we reward successive approximations of a target behaviour. Why is shaping needed? Remember that in order for reinforcement to work, the organism must first display the behaviour. Shaping is needed because it is extremely unlikely that an organism will display anything but the simplest of behaviours spontaneously. In shaping, behaviours are broken down into many small, achievable steps. The specific steps used in the process are the following:

- Reinforce any response that resembles the desired behaviour.

- Then reinforce the response that more closely resembles the desired behaviour. You will no longer reinforce the previously reinforced response.

- Next, begin to reinforce the response that even more closely resembles the desired behaviour.

- Continue to reinforce closer and closer approximations of the desired behaviour.

- Finally, only reinforce the desired behaviour.

Shaping is often used in teaching a complex behaviour or chain of behaviours. Skinner used shaping to teach pigeons not only such relatively simple behaviours as pecking a disk in a Skinner box, but also many unusual and entertaining behaviours, such as turning in circles, walking in figure eights, and even playing ping pong; the technique is commonly used by animal trainers today. An important part of shaping is stimulus discrimination. Recall Pavlov’s dogs; he trained them to respond to the tone of a bell, and not to similar tones or sounds. This discrimination is also important in operant conditioning and in shaping behaviour. Watch this video of Skinner’s pigeons playing ping pong to learn more.

Watch this video: BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip (1 minute)

“BF Skinner Foundation – Pigeon Ping Pong Clip” video by bfskinnerfoundation is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

It’s easy to see how shaping is effective in teaching behaviours to animals, but how does shaping work with humans? Let’s consider a parent whose goal is to have their child learn to clean their room. The parent uses shaping to help the child master steps toward the goal. Instead of performing the entire task, they set up these steps and reinforce each step. First, the child cleans up one toy. Second, the child cleans up five toys. Third, the child chooses whether to pick up ten toys or put their books and clothes away. Fourth, the child cleans up everything except two toys. Finally, the child cleans their entire room.

Primary and Secondary Reinforcers

Rewards such as stickers, praise, money, toys, and more can be used to reinforce learning. Let’s go back to Skinner’s rats again. How did the rats learn to press the lever in the Skinner box? They were rewarded with food each time they pressed the lever. For animals, food would be an obvious reinforcer.

What would be a good reinforcer for humans? For your child Karson, it was the promise of a toy when they cleaned their room. How about Sydney, the soccer player? If you gave Sydney a piece of candy every time Sydney scored a goal, you would be using a primary reinforcer. Primary reinforcers are reinforcers that have innate reinforcing qualities. These kinds of reinforcers are not learned. Water, food, sleep, shelter, sex, and touch, among others, are primary reinforcers. Pleasure is also a primary reinforcer. Organisms do not lose their drive for these things. For most people, jumping in a cool lake on a very hot day would be reinforcing and the cool lake would be innately reinforcing; the water would cool the person off (a physical need), as well as provide pleasure.

A secondary reinforcer has no inherent value and only has reinforcing qualities when linked with a primary reinforcer. Praise, linked to affection, is one example of a secondary reinforcer, as when you called out “Great shot!” every time Sydney made a goal. Another example, money, is only worth something when you can use it to buy other things—either things that satisfy basic needs (food, water, shelter—all primary reinforcers) or other secondary reinforcers. If you were on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and you had stacks of money, the money would not be useful if you could not spend it. What about the stickers on the behaviour chart? They also are secondary reinforcers.

Sometimes, instead of stickers on a sticker chart, a token is used. Tokens, which are also secondary reinforcers, can then be traded in for rewards and prizes. Entire behaviour management systems, known as token economies, are built around the use of these kinds of token reinforcers. Token economies have been found to be very effective at modifying behaviour in a variety of settings such as schools, prisons, and mental hospitals. For example, a study by Cangi and Daly (2013) found that use of a token economy increased appropriate social behaviours and reduced inappropriate behaviours in a group of autistic school children. Autistic children tend to exhibit disruptive behaviours such as pinching and hitting. When the children in the study exhibited appropriate behaviour (not hitting or pinching), they received a “quiet hands” token. When they hit or pinched, they lost a token. The children could then exchange specified amounts of tokens for minutes of playtime.

Everyday Connection: Behaviour Modification in Children

Parents and teachers often use behaviour modification to change a child’s behaviour. Behaviour modification uses the principles of operant conditioning to accomplish behaviour change so that undesirable behaviours are switched for more socially acceptable ones. Some teachers and parents create a sticker chart, in which several behaviours are listed (Figure L.11). Sticker charts are a form of token economies, as described in the text. Each time children perform the behaviour, they get a sticker, and after a certain number of stickers, they get a prize, or reinforcer. The goal is to increase acceptable behaviours and decrease misbehaviour.

Remember, it is best to reinforce desired behaviours, rather than to use punishment. In the classroom, the teacher can reinforce a wide range of behaviours, from students raising their hands, to walking quietly in the hall, to turning in their homework. At home, parents might create a behaviour chart that rewards children for things such as putting away toys, brushing their teeth, and helping with dinner. In order for behaviour modification to be effective, the reinforcement needs to be connected with the behaviour; the reinforcement must matter to the child and be done consistently.

Time-out is another popular technique used in behaviour modification with children. It operates on the principle of negative punishment. When a child demonstrates an undesirable behaviour, she is removed from the desirable activity at hand (Figure LE.12). For example, say that Paton and their sibling Bennet are playing with building blocks. Paton throws some blocks at Bennet, so you give Paton a warning that they will go to time-out if they do it again. A few minutes later, Paton throws more blocks at Bennet. You remove Paton from the room for a few minutes. When Paton comes back, they don’t throw blocks.

There are several important points that you should know if you plan to implement time-out as a behaviour modification technique. First, make sure the child is being removed from a desirable activity and placed in a less desirable location. If the activity is something undesirable for the child, this technique will backfire because it is more enjoyable for the child to be removed from the activity. Second, the length of the time-out is important. The general rule of thumb is one minute for each year of the child’s age. Sophia is five; therefore, she sits in a time-out for five minutes. Setting a timer helps children know how long they have to sit in time-out. Finally, as a caregiver, keep several guidelines in mind over the course of a time-out: remain calm when directing your child to time-out; ignore your child during time- out (because caregiver attention may reinforce misbehaviour); and give the child a hug or a kind word when time-out is over.

Reinforcement Schedules

Remember, the best way to teach a person or animal a behaviour is to use positive reinforcement. For example, Skinner used positive reinforcement to teach rats to press a lever in a Skinner box. At first, the rat might randomly hit the lever while exploring the box, and out would come a pellet of food. After eating the pellet, what do you think the hungry rat did next? It hit the lever again, and received another pellet of food. Each time the rat hit the lever, a pellet of food came out. When an organism receives a reinforcer each time it displays a behaviour, it is called continuous reinforcement. This reinforcement schedule is the quickest way to teach someone a behaviour, and it is especially effective in training a new behaviour. Let’s look back at the dog that was learning to sit earlier in the chapter. Now, each time the dog sits, you give the dog a treat. Timing is important here: you will be most successful if you present the reinforcer immediately after the dog sits, so that the dog can make an association between the target behaviour (sitting) and the consequence (getting a treat).

Watch this video clip of veterinarian Dr. Sophia Yin shaping a dog’s behaviour using the steps outlined above, to learn more.

Watch this video: Free Shaping with an Australian Cattledog (3 minutes)

“Free Shaping with an Australian CattleDog | drsophiayin.com” video by CattleDog Publishing® is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

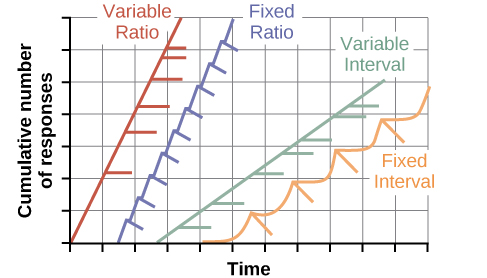

Once a behaviour is trained, researchers and trainers often turn to another type of reinforcement schedule—partial reinforcement. In partial reinforcement, also referred to as intermittent reinforcement, the person or animal does not get reinforced every time they perform the desired behaviour. There are several different types of partial reinforcement schedules (Table LE.3). These schedules are described as either fixed or variable, and as either interval or ratio. Fixed refers to the number of responses between reinforcements, or the amount of time between reinforcements, which is set and unchanging. Variable refers to the number of responses or amount of time between reinforcements, which varies or changes. Interval means the schedule is based on the time between reinforcements, and ratio means the schedule is based on the number of responses between reinforcements.

| Reinforcement Schedule | Description | Result | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Interval | Reinforcement is delivered at predictable time intervals (e.g., after 5, 10, 15, and 20 minutes). | Moderate response rate with significant pauses after reinforcement | Hospital patient uses patient-controlled, doctor-timed pain relief |

| Variable Interval | Reinforcement is delivered at unpredictable time intervals (e.g., after 5, 7, 10, and 20 minutes). | Moderate yet steady response rate | Checking Instagram for notifications |

| Fixed Ratio | Reinforcement is delivered after a predictable number of responses (e.g., after 2, 4, 6, and 8 responses). | High response rate with pauses after reinforcement | Piecework—factory worker getting paid for every x number of items manufactured |

| Variable Ratio | Reinforcement is delivered after an unpredictable number of responses (e.g., after 1, 4, 5, and 9 responses). | High and steady response rate | Gambling |

Now let’s combine these four terms:

- A fixed interval reinforcement schedule is when behaviour is rewarded after a set amount of time. For example, June undergoes major surgery in a hospital. During recovery, June is expected to experience pain and will require prescription medications for pain relief. June is given an IV drip with a patient-controlled painkiller. June’s doctor sets a limit: one dose per hour. June pushes a button when pain becomes difficult, and they receive a dose of medication. Since the reward (pain relief) only occurs on a fixed interval, there is no point in exhibiting the behaviour when it will not be rewarded.

- With a variable interval reinforcement schedule, the person or animal gets the reinforcement based on varying amounts of time, which are unpredictable. Say that Tate is the manager at a fast-food restaurant. Every once in a while someone from the quality control division comes to Tate’s restaurant. If the restaurant is clean and the service is fast, everyone on that shift earns a $20 bonus. Tate never knows when the quality control person will show up, so they always try to keep the restaurant clean and ensure that their employees provide prompt and courteous service. Tate’s productivity regarding prompt service and keeping a clean restaurant are steady because Tate wants their crew to earn the bonus.

- With a fixed ratio reinforcement schedule, there are a set number of responses that must occur before the behaviour is rewarded. Reed sells glasses at an eyeglass store, and earns a commission every time they sell a pair of glasses. Reed always tries to sell people more pairs of glasses, including prescription sunglasses or a backup pair, so they can increase their commission. Reed does not care if the person really needs the prescription sunglasses, they just want the bonus. The quality of what Reed sells does not matter because Reed’s commission is not based on quality; it’s only based on the number of pairs sold. This distinction in the quality of performance can help determine which reinforcement method is most appropriate for a particular situation. Fixed ratios are better suited to optimize the quantity of output, whereas a fixed interval, in which the reward is not quantity based, can lead to a higher quality of output.

- In a variable ratio reinforcement schedule, the number of responses needed for a reward varies. This is the most powerful partial reinforcement schedule. An example of the variable ratio reinforcement schedule is gambling. Imagine that Quinn—generally a smart, thrifty person—visits Las Vegas for the first time. Quinn is not a gambler, but out of curiosity they put a quarter into the slot machine, and then another, and another. Nothing happens. Two dollars in quarters later, Quinn’s curiosity is fading, and they are just about to quit. But then, the machine lights up, bells go off, and Quinn gets 50 quarters back. That’s more like it! Quinn gets back to inserting quarters with renewed interest, and a few minutes later they have used up all the gains and are $10 in the hole. Now might be a sensible time to quit. And yet, Quinn keeps putting money into the slot machine because they never know when the next reinforcement is coming. Quinn keeps thinking that with the next quarter they could win $50, or $100, or even more. Because the reinforcement schedule in most types of gambling has a variable ratio schedule, people keep trying and hoping that the next time they will win big. This is one of the reasons that gambling is so addictive—and so resistant to extinction.

In operant conditioning, extinction of a reinforced behaviour occurs at some point after reinforcement stops, and the speed at which this happens depends on the reinforcement schedule. In a variable ratio schedule, the point of extinction comes very slowly, as described above. But in the other reinforcement schedules, extinction may come quickly. For example, if June presses the button for the pain relief medication before the allotted time their doctor has approved, no medication is administered. June is on a fixed interval reinforcement schedule (dosed hourly), so extinction occurs quickly when reinforcement doesn’t come at the expected time. Among the reinforcement schedules, variable ratio is the most productive and the most resistant to extinction. Fixed interval is the least productive and the easiest to extinguish (Figure L.13).

Dig Deeper: Gambling and the Brain

Skinner (1953) stated, “If the gambling establishment cannot persuade a patron to turn over money with no return, it may achieve the same effect by returning part of the patron’s money on a variable- ratio schedule” (p. 397).

Skinner uses gambling as an example of the power of the variable-ratio reinforcement schedule for maintaining behaviour even during long periods without any reinforcement. In fact, Skinner was so confident in his knowledge of gambling addiction that he even claimed he could turn a pigeon into a pathological gambler (“Skinner’s Utopia,” 1971). It is indeed true that variable-ratio schedules keep behaviour quite persistent—just imagine the frequency of a child’s tantrums if a parent gives in even once to the behaviour. The occasional reward makes it almost impossible to stop the behaviour.

Recent research in rats has failed to support Skinner’s idea that training on variable-ratio schedules alone causes pathological gambling (Laskowski et al., 2019). However, other research suggests that gambling does seem to work on the brain in the same way as most addictive drugs, and so there may be some combination of brain chemistry and reinforcement schedule that could lead to problem gambling (Figure L.14). Specifically, modern research shows the connection between gambling and the activation of the reward centres of the brain that use the neurotransmitter (brain chemical) dopamine (Murch & Clark, 2016).

Interestingly, gamblers don’t even have to win to experience the “rush” of dopamine in the brain. “Near misses,” or almost winning but not actually winning, also have been shown to increase activity in the ventral striatum and other brain reward centres that use dopamine (Chase & Clark, 2010). These brain effects are almost identical to those produced by addictive drugs like cocaine and heroin (Murch & Clark, 2016). Based on the neuroscientific evidence showing these similarities, the DSM-5 now considers gambling an addiction, while earlier versions of the DSM classified gambling as an impulse control disorder.

In addition to dopamine, gambling also appears to involve other neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine and serotonin (Potenza, 2013).

Norepinephrine is secreted when a person feels stress, arousal, or thrill. It may be that pathological gamblers use gambling to increase their levels of this neurotransmitter. Deficiencies in serotonin might also contribute to compulsive behaviour, including a gambling addiction (Potenza, 2013).

It may be that pathological gamblers’ brains are different than those of other people, and perhaps this difference may somehow have led to their gambling addiction, as these studies seem to suggest. However, it is very difficult to ascertain the cause because it is impossible to conduct a true experiment (it would be unethical to try to turn randomly assigned participants into problem gamblers). Therefore, it may be that causation actually moves in the opposite direction—perhaps the act of gambling somehow changes neurotransmitter levels in some gamblers’ brains. It also is possible that some overlooked factor, or confounding variable, played a role in both the gambling addiction and the differences in brain chemistry.

Other Types of Learning

John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner were behaviourists who believed that all learning could be explained by the processes of conditioning—that is, that associations, and associations alone, influence learning. But some kinds of learning are very difficult to explain using only conditioning. Thus, although classical and operant conditioning play a key role in learning, they constitute only a part of the total picture. One type of learning that is not determined only by conditioning occurs when we suddenly find the solution to a problem, as if the idea just popped into our head. This type of learning is known as insight, the sudden understanding of a solution to a problem. The German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1957-1925) carefully observed what happened when he presented chimpanzees with a problem that was not easy for them to solve, such as placing food in an area that was too high in the cage to be reached. He found that the chimps first engaged in trial-and-error attempts at solving the problem, but when these failed they seemed to stop and contemplate for a while. Then, after this period of contemplation, they would suddenly seem to know how to solve the problem, for instance, by using a stick to knock the food down or by standing on a chair to reach it. Köhler argued that it was this flash of insight, not the prior trial-and-error approaches that were so important for conditioning theories, that allowed the animals to solve the problem.

Strict behaviourists like Watson and Skinner focused exclusively on studying behaviour rather than cognition (such as thoughts and expectations). In fact, Skinner was such a staunch believer that cognition didn’t matter that his ideas were considered radical behaviourism. Skinner considered the mind a “black box”—something completely unknowable—and, therefore, something not to be studied. However, another behaviourist, Edward C. Tolman, had a different opinion. Tolman’s experiments with rats demonstrated that organisms can learn even if they do not receive immediate reinforcement (Tolman & Honzik, 1930; Tolman, Ritchie, & Kalish, 1946). This finding was in conflict with the prevailing idea at the time that reinforcement must be immediate in order for learning to occur, thus suggesting a cognitive aspect to learning.

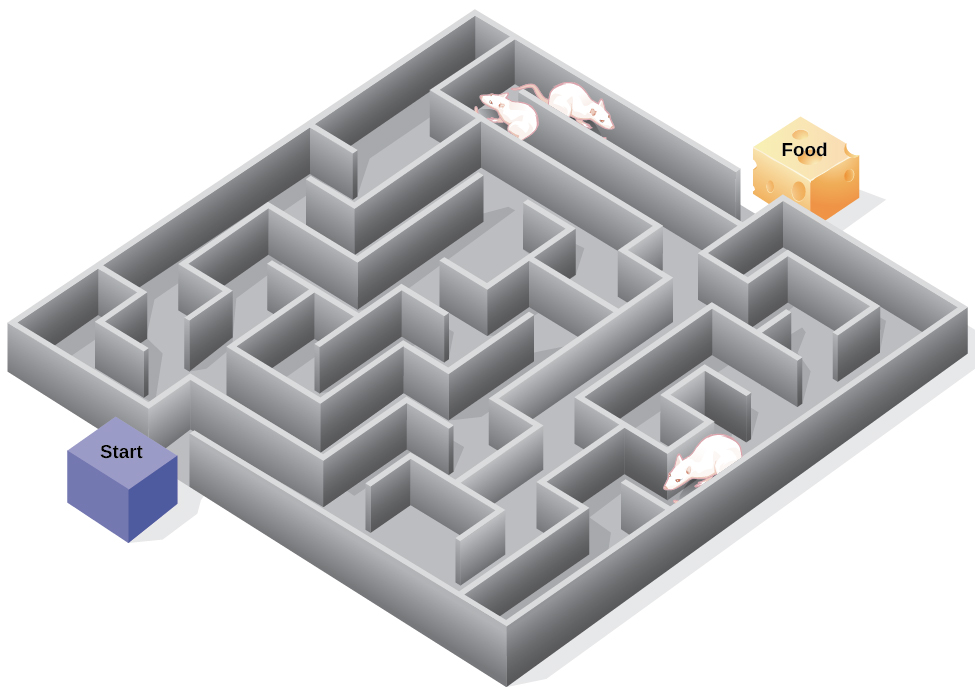

Edward Tolman studied the behaviour of three groups of rats that were learning to navigate through mazes (Tolman & Honzik, 1930). The first group always received a reward of food at the end of the maze but the second group never received any reward. The third group did not receive any reward for the first 10 days and then began receiving rewards on the 11th day of the experimental period. As you might expect when considering the principles of conditioning, the rats in the first group quickly learned to negotiate the maze, while the rats of the second group seemed to wander aimlessly through it. The rats in the third group, however, although they wandered aimlessly for the first 10 days, quickly learned to navigate to the end of the maze as soon as they received food on day 11. By the next day, the rats in the third group had caught up in their learning to the rats that had been rewarded from the beginning. Tolman argued that this was because as the unreinforced rats explored the maze, they developed a cognitive map: a mental picture of the layout of the maze (Figure LE.15). As soon as the rats became aware of the food (beginning on the 11th day), they were able to find their way through the maze quickly, just as quickly as the comparison group, which had been rewarded with food all along. This is known as latent learning: learning that occurs but is not observable in behaviour until there is a reason to demonstrate it.

Latent learning also occurs in humans. Children may learn by watching the actions of their parents but only demonstrate it at a later date, when the learned material is needed. For example, suppose that Zan’s parent drives Zan to school every day. In this way, Zan learns the route from their house to their school, but Zan’s never driven there themselves, so they have not had a chance to demonstrate that they’ve learned the way. One morning Zan’s parent has to leave early for a meeting, so they can’t drive Zan to school. Instead, Zan follows the same route on their bike that Zan’s parent would have taken in the car. This demonstrates latent learning. Zan had learned the route to school, but had no need to demonstrate this knowledge earlier.

Image Attributions

Figure LE.10. Figure 6.10 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License and contains modifications of the following works: B.F. Skinner at Harvard circa 1950 (cropped) by Silly rabbit is licensed under a CC BY 30 Unported license and Skinner box scheme 01 by AndreasJS is licensed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.

Figure LE.11. “Sticker chart” by Abigail Batchelder is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

Figure LE.12. (a) “Kids on test climb rock” by Rachel is licensed under an Unsplash licence, (b) “boy sitting on concrete bench” by Kelly Sikkema is licensed under an Unsplash licence.

Figure LE.13. “Schedule of reinforcement” is in the public domain.

Figure LE.14. “Playing cards on brown wooden table” by Aidan Howe is licensed under an Unsplash licence.

Figure LE.15. Figure 6.15 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License and contains modifications of the following works: “Maze Puzzle (Blender)” by FutUndBeidl is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).