Chapter 14. Personality

Personality Introduction

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 10 minutes

Twins Separated at Birth

Paula Bernstein and Elyse Schein were identical twins who were adopted into separate families immediately after their births in 1968. It was only at the age of 35 that the twins were reunited and discovered how similar they were to each other.

Paula Bernstein grew up in a happy home in suburban New York. She loved her adopted parents and older brother and even wrote an article titled “Why I Don’t Want to Find My Birth Mother.” Elyse’s childhood, also a happy one, was followed by university and then film school abroad.

In 2003, 35 years after she was adopted, Elyse, acting on a whim, inquired about her biological family at the adoption agency. The response came back: “You were born on October 9, 1968, at 12:51 p.m., the younger of twin girls. You’ve got a twin sister named Paula, and she’s looking for you.”

“Oh, my God. I’m a twin! Can you believe this? Is this really happening?” Elyse cried.

Elyse dialed Paula’s phone number: “It’s almost like I’m hearing my own voice in a recorder back at me,” she said.

“It’s funny because I feel like in a way I was talking to an old, close friend I never knew I had. We had an immediate intimacy, and yet, we didn’t know each other at all,” Paula said.

The two women met for the first time at a café for lunch and talked until the late evening. “We had 35 years to catch up on,” said Paula. “How do you start asking somebody, ‘What have you been up to since we shared a womb together?’ Where do you start?” With each new detail revealed, the twins learned about their remarkable similarities. They’d both gone to graduate school in film. They both loved to write, and they had both edited their high school yearbooks. They have similar taste in music.

“I think, you know, when we met it was undeniable that we were twins. Looking at this person, you are able to gaze into your own eyes and see yourself from the outside. This identical individual has the exact same DNA and is essentially your clone. We don’t have to imagine,” Paula said.

Now they finally feel like sisters. “But it’s perhaps even closer than sisters,” Elyse said, “because we’re also twins.”

The following YouTube video provides further details about the experiences of Paula Bernstein and Elyse Schein.

Watch this video: Identical Twins Separated at Birth (9 minutes)

“Identical Twins Separated at Birth” video by Strombo is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Introduction to Personality

In this chapter, we will consider the wide variety of personality traits found in human beings. We’ll consider how and when personality influences our behaviour and how well we perceive the personalities of others. We will also consider how psychologists measure personality and the extent to which personality is caused by nature versus nurture. The fundamental goal of personality psychologists is to understand what makes people different from each other by studying individual differences, but also what makes them similar, as is the case with people who share genes, such as Paula Bernstein and Elyse Schein.

Personality is defined as an individual’s consistent patterns of feeling, thinking, and behaving (John et al., 2008). The word personality comes from the Latin word persona. In the ancient world, a persona was a mask worn by an actor. When we say that Bill is fun, that Marian is shy, or that Frank is helpful, we mean that we believe that these people have stable individual characteristics — their personalities.

Understanding personality is part of our human nature, and helps us in life. It can help us understand why people do the things they do. Knowing a person’s personality may also enable us to predict how they might act in the future and in different situations.

The concept of personality has been studied for at least 2,000 years, beginning with Hippocrates (460–370 BC). Hippocrates theorised that personality traits and human behaviours are based on four separate temperaments associated with four fluids (“humours”) of the body: choleric (yellow bile from the liver), melancholic (black bile from the kidneys), sanguine (red blood from the heart), and phlegmatic (white phlegm from the lungs). Based on Hippocrates’s theory, another ancient Greek physician, surgeon, and philosopher, Galen (c. AD 129–200), suggested that personality differences could be explained by imbalances in the humours and that each person exhibits one of the four temperaments. For example, the choleric person is passionate, ambitious, and bold; the melancholic person is reserved, anxious, and unhappy; the sanguine person is joyful, eager, and optimistic; and the phlegmatic person is calm, reliable, and thoughtful. Galen’s theory was prevalent for over 1,000 years and continued to be popular through the Middle Ages.

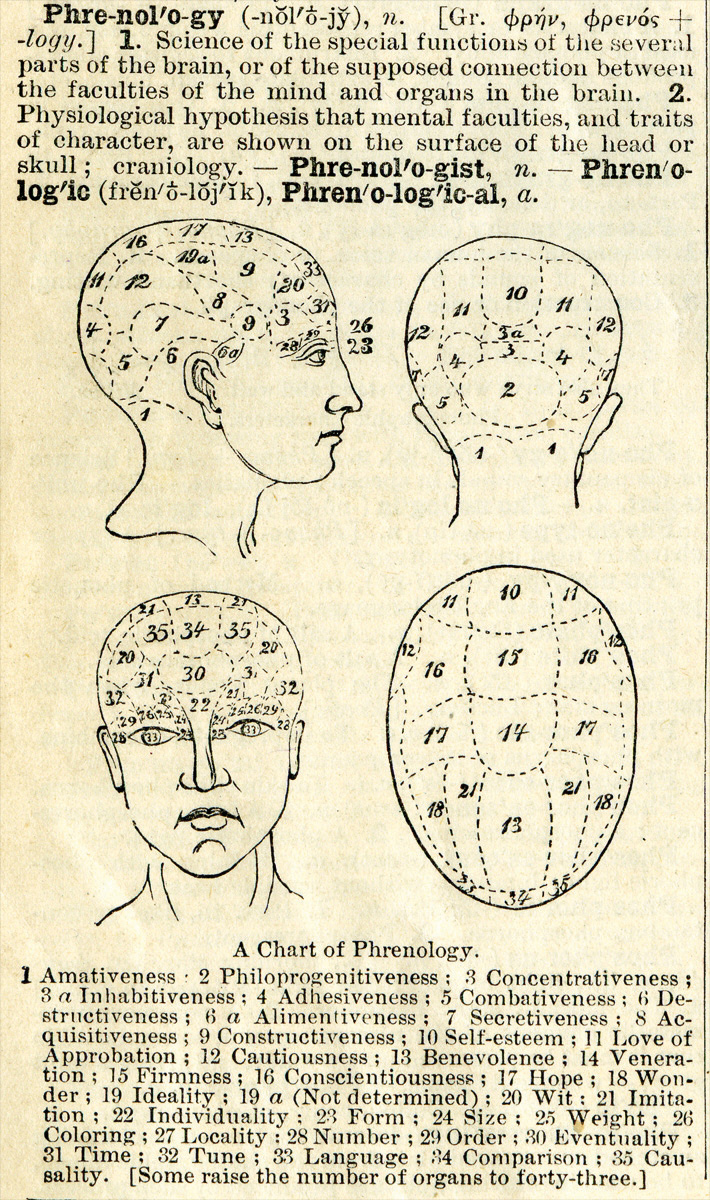

In 1780, Franz Gall, a German physician, proposed that the distances between bumps on the skull informed us whether a person was friendly, prideful, murderous, kind, good with languages, and so on. Gall’s approach, known as phrenology, was very popular; however, because careful scientific research did not validate the predictions of the theory, phrenology has now been discredited in contemporary psychology.

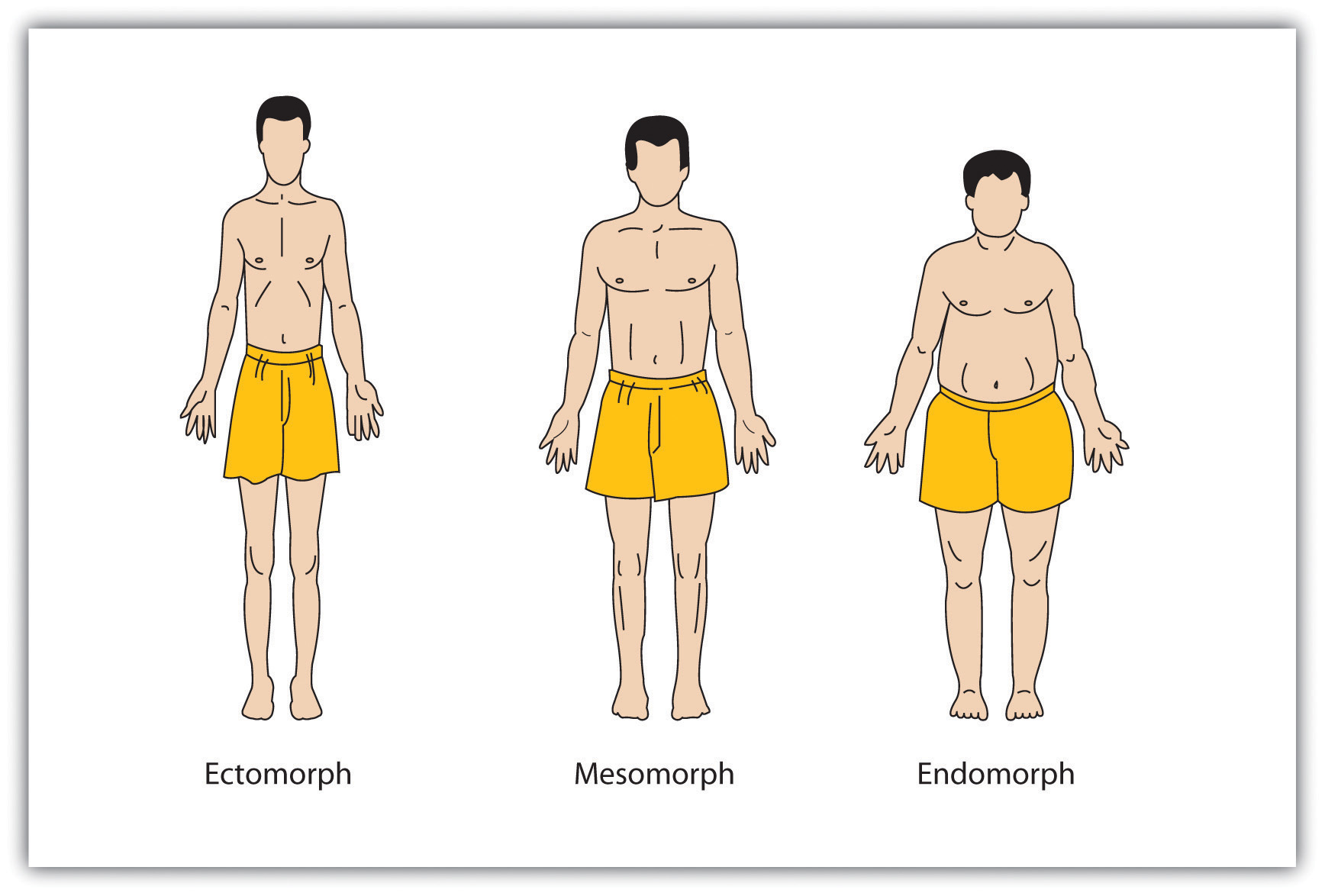

Another approach, known as somatology, championed by the psychologist William H. Sheldon (1898–1977), was based on the idea that we could determine personality from people’s body types. Sheldon (1940) argued that people with more body fat and a rounder physique (i.e., endomorphs) were more likely to be assertive and bold, whereas thinner people (i.e., ectomorphs) were more likely to be introverted and intellectual. As with phrenology, scientific research did not validate the predictions of the theory, and somatology has now too been discredited in contemporary psychology.

Image Attributions

Figure PE.1. Figure 11.2 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License

Figure PE.2. 1895-Dictionary-Phrenolog by unknown author is in the public domain.

Figure PE.3. Figure 14.2 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).