Chapter 18. Psychological Disorders

Perspectives on Psychological Disorders

Leanne Stevens; Jennifer Stamp; Kevin LeBlanc (editors - original chapter); and Jessica Motherwell McFarlane (editor - adapted chapter)

Approximate reading time: 13 minutes

Scientists, mental health professionals, and cultural healers may adopt different perspectives in attempting to understand or explain the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the development of a psychological disorder. The specific perspective used in explaining a psychological disorder is extremely important. Each perspective explains psychological disorders, their causes or etiology, and effective treatments from a different viewpoint. Different perspectives provide alternate ways for how to think about the nature of psychopathology.

Supernatural Perspectives of Psychological Disorders

For centuries, psychological disorders were viewed from a supernatural perspective: attributed to a force beyond scientific understanding. Those afflicted were thought to be practitioners of black magic or possessed by spirits (Figure PD.7) (Maher & Maher, 1985). For example, convents throughout Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries reported hundreds of nuns falling into a state of frenzy in which the afflicted foamed at the mouth, screamed and convulsed, sexually propositioned priests, and confessed to having carnal relations with devils or Christ. Although today these cases would suggest serious mental illness, at the time, these events were routinely explained as possession by devilish forces (Waller, 2009a). Such beliefs in supernatural causes of mental illness are still held in some societies today; for example, beliefs that supernatural forces cause mental illness are common in some cultures in modern-day Nigeria (Aghukwa, 2012).

Dancing Mania

Between the 11th and 17th centuries, a curious epidemic swept across Western Europe. Groups of people would suddenly begin to dance with wild abandon. This compulsion to dance, referred to as dancing mania, sometimes gripped thousands of people at a time (Figure PD.8). Historical accounts indicate that those afflicted would sometimes dance with bruised and bloody feet for days or weeks, screaming of terrible visions and begging priests and monks to save their souls (Waller, 2009b). What caused dancing mania is not known, but several explanations have been proposed, including spider venom and ergot poisoning (“Dancing Mania,” 2011).

Historian John Waller (2009a, 2009b) has provided a comprehensive and convincing explanation of dancing mania that suggests the phenomenon was attributable to a combination of three factors: (1) psychological distress, (2) social contagion, and (3) belief in supernatural forces. Waller argued that various disasters of the time (such as famine, plagues, and floods) produced high levels of psychological distress that could increase the likelihood of succumbing to an involuntary trance state. Waller indicated that anthropological studies and accounts of possession rituals show that people are more likely to enter a trance state if they expect it to happen, and that entranced individuals behave in a ritualistic manner, their thoughts and behaviour shaped by the spiritual beliefs of their culture. Thus, during periods of extreme physical and mental distress, all it took were a few people who believed themselves to have been afflicted with a dancing curse to slip into a spontaneous trance and then act out the part of one who is cursed by dancing for days on end.

Biological Perspectives of Psychological Disorders

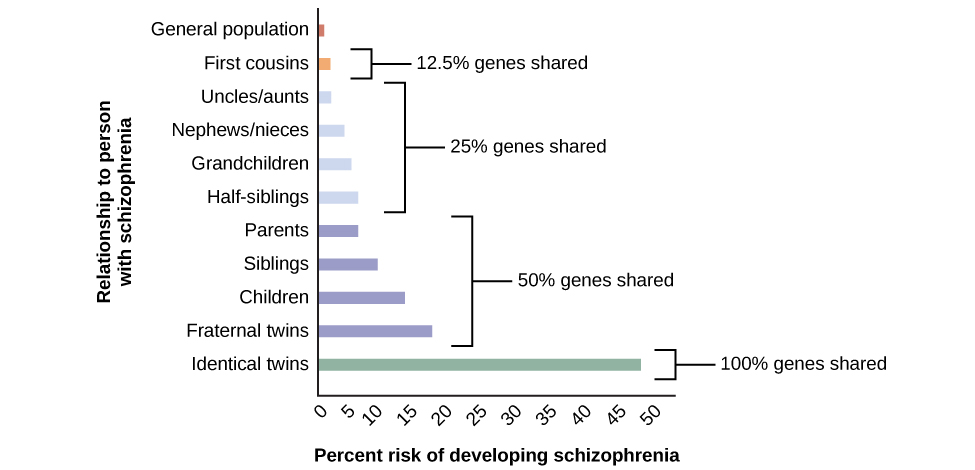

The biological perspective views psychological disorders as linked to biological phenomena, such as genetic factors, chemical imbalances, and brain abnormalities; it has gained considerable attention and acceptance in recent decades (Wyatt & Midkiff, 2006). Evidence from many sources indicates that most psychological disorders have a genetic component; in fact, there is little dispute that some disorders are largely due to genetic factors. The graph in Figure PD.9 shows heritability estimates for schizophrenia.

Findings such as these have led many of today’s researchers to search for specific genes and genetic mutations that contribute to mental disorders. Also, sophisticated neural imaging technology in recent decades has revealed how abnormalities in brain structure and function might be directly involved in many disorders, and advances in our understanding of neurotransmitters and hormones have yielded insights into their possible connections. The biological perspective is currently thriving in the study of psychological disorders.

The Diathesis-Stress Model of Psychological Disorders

Despite advances in understanding the biological basis of psychological disorders, the psychosocial perspective is still very important. This perspective emphasises the importance of learning, stress, faulty and self-defeating thinking patterns, and environmental factors. Perhaps the best way to think about psychological disorders, then, is to view them as originating from a combination of biological and psychological processes. Many develop not from a single cause, but from a delicate fusion between partly biological and partly psychosocial factors.

Study hint: Diathesis and Stress

Diathesis: This term comes from a Greek word meaning “disposition” or “predisposition.” It refers to an underlying vulnerability or tendency that a person has, which makes them more susceptible to developing a disorder. This predisposition can be biological (such as a genetic tendency toward depression) or psychological (like a habitual way of thinking negatively about oneself and the world).

Stress: This refers to challenging or adverse events in a person’s life. These can include experiences like childhood abuse, traumatic events, or significant negative life changes. Stressful events can trigger the onset of a disorder in someone who has a diathesis.

The diathesis-stress model (Zuckerman, 1999) integrates biological and psychosocial factors to predict the likelihood of a disorder. This diathesis-stress model suggests that people with an underlying predisposition for a disorder (i.e., a diathesis) are more likely than others to develop a disorder when faced with adverse environmental or psychological events (i.e., stress), such as childhood maltreatment, negative life events, trauma, and so on. A diathesis is not always a biological vulnerability to an illness; some diatheses may be psychological (e.g., a tendency to think about life events in a pessimistic, self-defeating way).

The key assumption of the diathesis-stress model is that both factors, diathesis and stress, are necessary in the development of a disorder. Different models explore the relationship between the two factors: the level of stress needed to produce the disorder is inversely proportional to the level of diathesis. Read Emma’s Case Study for an application of the Diathesis-Stress Model.

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Diathesis Stress (5 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Diathesis Stress” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Here is the Tricky Topics: Diathesis Stress transcript.

Image Attributions

Figure PD.7. Portion of a Public Domain Image.

Figure PD.8. Public Domain Image.

Figure PD.9. Figure 15.8 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).