Chapter 14. Personality

Psychodynamic and Humanistic Views of Personality

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 25 minutes

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Recognise the key concepts in Freudian, Adlerian, Jungian, Horney’s, Fromm’s, Erikson’s, and Rogers’s theory

- Critique the Freudian theories

- Respect the accomplishments of the neo-Freudians and Rogers

One of the most important psychological approaches to understanding personality is based on the theory of the Austrian physician and psychologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). His approach, known as psychodynamics, focuses on the role of unconscious thoughts, feelings, and memories. Freud is probably the best known of all psychologists, in part because of his impressive observation and analysis of personality. Freud built his theory of personality by studying patients, mostly women, who were experiencing a condition called hysteria. Hysteria, a historical term, was a mix of emotional and physical symptoms like chronic pain, fainting, seizures, and paralysis. Some hysterical patients, when under hypnosis, revealed they had gone through traumatic sexual experiences as children. During these sessions, patients often experienced strong emotions, known as catharsis, and their symptoms improved afterward. Freud believed that these issues were more related to a person’s mind than their body. Like many theories, some of Freud’s clever ideas have been shown to be partly wrong, but some parts of his theories still have an impact on psychology today.

In terms of free will, Freud did not believe that we were able to control our own behaviours. Rather, he believed that all behaviours are predetermined by motivations that lie outside our awareness, in the unconscious. These forces show themselves in our dreams, in neurotic symptoms such as obsessions, while we are under hypnosis, and in Freudian “slips of the tongue” in which people reveal their unconscious desires in language. Freud argued that we rarely understand why we do what we do. For Freud, the mind was like an iceberg. In this analogy, the unconscious is much larger, but also out of sight, in comparison to the conscious of which we are aware.

Id, Ego, and Superego

Freud proposed that the mind is divided into three components — id, ego, and superego — and that the interactions and conflicts among the components create personality (Freud, 1923/1949). According to Freudian theory, the id is the component of personality that forms the basis of our most primitive impulses. The id is entirely unconscious, and it drives our most important motivations, including the sexual drive (i.e., libido) and the aggressive drive. According to Freud, the id is driven by the pleasure principle, which is the desire for immediate gratification of our sexual and aggressive urges. The id is why we smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, view pornography, tell mean jokes about people, and engage in other fun or harmful behaviours.

In contrast to the id, the function of the ego is based on the reality principle, which is the idea that we must delay gratification of our basic motivations until the appropriate time with the appropriate outlet. The ego is the largely conscious controller. We may wish to scream, yell, or hit, and yet our ego normally tells us to wait, reflect, and choose a more appropriate response.

The superego represents our sense of right and wrong. The superego tells us all the things that we shouldn’t do, based on our interpretation of the duties and obligations of society. The superego strives for perfection, and when we fail to live up to its demands, we feel guilty.

Freud believed that psychological disorders, and particularly the experience of anxiety, occur when there is conflict or imbalance among the id, ego, and superego. When the ego finds that the id is pressing too hard for immediate pleasure, it attempts to correct for this problem, often through the use of defence mechanisms, which are unconscious psychological strategies used to cope with anxiety and maintain a positive self-image.

Freud believed that the defence mechanisms were essential for effective coping with everyday life, but that any of them could be overused. For example, let’s say Joe is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be rejected by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay will result in social rejection) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe may find himself making gay jokes or picking on a school peer who is gay.

There are several different types of defence mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. As an analogy, let’s say your car is making a strange noise, but because you do not have the money to get it fixed, you just turn up the radio so that you no longer hear the strange noise. Eventually you forget about it. Similarly, in the human mind, if a memory is too overwhelming to deal with, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness (Freud, 1920). The table below identifies the major Freudian defence mechanisms.

| Defence Mechanism | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Repression | Pushing anxiety-arousing thoughts into the unconscious | A person who witnesses the death of a loved one is later unable to remember anything about the event. |

| Displacement | Diverting threatening impulses away from the source of the anxiety and toward a more acceptable source | A student who is angry at her professor for a low grade lashes out at her roommate, who is a safer target of her anger. |

| Projection | Disguising threatening impulses by attributing them to others | A man with powerful unconscious sexual desires for women claims that women use him as a sex object. |

| Rationalisation | Justifying one’s own negative behaviour in an irrational way | A drama student convinces herself that getting the part in the play wasn’t that important after all. |

| Reaction formation | Making unacceptable motivations appear as their exact opposite | Jane is sexually attracted to Jake, but she claims in public that she intensely dislikes him. |

| Regression | Retreating to an earlier, more childlike, and safer stage of development | A university student who is worried about an important test begins to bite his nails. |

| Sublimation | Channeling unacceptable sexual or aggressive desires into acceptable activities | A person creates music or art to express sexual drives. |

The most controversial part of Freudian theory is its explanations of personality development. Freud argued that personality is developed through a series of psychosexual stages, each focusing on pleasure from a different part of the body. The table below provides details on stages of psychosexual development. Freud believed that sexuality started when you were a baby, and how you dealt with each stage affected how your personality developed as you grew up.

| Stage | Age range | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | Birth to 18 months | Pleasure comes from the mouth in the form of sucking, biting, and chewing |

| Anal | 18 months to 3 years | Pleasure comes from bowel and bladder elimination, and conflict is with the constraints of toilet training. |

| Phallic | 3 to 5 years | Pleasure comes from the genitals, and the conflict is with sexual desires for the opposite-sex parent. |

| Latency | 5 years to puberty | Sexual feelings are less important. |

| Genital | Puberty and older | If prior stages have been properly reached, mature sexual orientation develops. |

During the oral stage (from birth to 18 months), the infant obtains sexual pleasure by sucking and drinking. If a baby doesn’t get enough or gets too much oral gratification, they might get stuck or fixated in this stage. Even as adults, when they feel stressed, they might act like they did when they were babies. According to Freud, a child who was underfed or neglected will become orally dependent as an adult and be likely to manipulate others to fulfill their needs rather than becoming independent. On the other hand, the child who was overfed or overly gratified will resist growing up and try to return to the prior state of dependency by acting helpless, demanding satisfaction from others, and acting in a needy way.

During the anal stage (from about 18 months to 3 years old), children desire to experience pleasure through bowel movements, but they are also being toilet trained to delay this gratification. Freud believed that if this toilet training was either too harsh or too lenient, children would become fixated in the anal stage and become likely to regress to this stage under stress as adults. If the child received too little anal gratification (i.e., if the parents had been very harsh about toilet training), the adult personality will be anal retentive, showing a tendency to be stingy and a compulsive seeking of order and tidiness. On the other hand, if the parents had been too lenient, the anal expulsive personality results, characterised by a lack of self-control and a tendency toward messiness and carelessness.

During the phallic stage (from 3 to about 5 years old), the genitals (i.e., the penis and the clitoris) become the main source of sexual pleasure. According to Freud, at this time children develop an unconscious attraction for the opposite-sex parent and a desire to replace the same-sex parent. Freud based his theory of sexual development on boys. He called this powerful desire the Oedipus complex, based on the Greek mythological character Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother before gouging his own eyes out when he learned what he had done. Freud argued that boys would normally abandon their love of the mother, eventually, and instead identify with the father, taking on the father’s personality characteristics. However, boys who do not successfully resolve the Oedipus complex will experience psychological problems later in life. Freud believed that a girl would also develop a sexual desire for her father and a sense of competition with her mother for his attention. Unlike boys, girls would experience penis envy, or a feeling of deprivation. Freud suggested that this feeling could affect girls’ thoughts and attitudes, particularly in their relationships with boys and men.

The latency stage is a period of relative calm that lasts from about 5 to 12 years old. Freud believed that sexual impulses were repressed at this time.

The genital stage begins at about 12 years of age. According to Freud, sexual impulses return at this time. If everything has been going well in a person’s development until now, they should be able to start forming mature romantic relationships. However, if there were problems that weren’t fixed earlier in their growing up, it might be hard for them to make close, loving connections with others.

Strengths and Limitations of Freudian Theories

Freud has probably had a greater impact on the public’s understanding of personality than any other thinker, and he has also in large part defined the early field of psychology. Although Freudian psychologists no longer talk about oral, anal, or genital fixations, they do continue to believe that our childhood experiences shape our personalities and our attachments with others, and they still make use of psychodynamic concepts when they conduct psychological therapy.

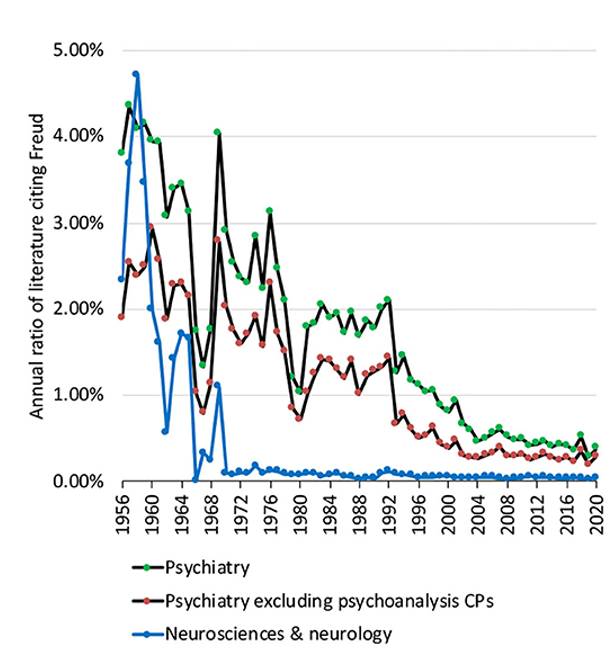

Nevertheless, Freud’s theories are less influential now than they have been in the past (Crews, 1998; Yeung, 2021). The problems are, first, testing Freudian theory is difficult because its predictions, especially about defense mechanisms, are often vague and unfalsifiable, and second, the aspects of the theory that can be tested often have not received much empirical support.

For example, although Freud claimed that children exposed to overly harsh toilet training would become fixated in the anal stage and thus be prone to excessive neatness, stinginess, and stubbornness in adulthood, research has found few reliable associations between toilet training practices and adult personality (Fisher & Greenberg, 1996).

There is also little scientific support for some of the Freudian defence mechanisms. For example, studies have failed to yield evidence for the existence of repression. People who are exposed to traumatic experiences in war have been found to remember their traumas only too well (Kihlstrom, 1997). Although we may attempt to push information that is anxiety-arousing into our unconscious, this often has the ironic effect of making us think about the information even more strongly than if we hadn’t tried to repress it (Newman et al., 1997). While children remember little of their childhood experiences, this is true of both negative and positive experiences, and probably is better explained in terms of the brain’s inability to form long-term memories than in terms of repression. On the other hand, Freud’s important idea that expressing or talking through one’s difficulties can be psychologically helpful has been supported in current research (Baddeley & Pennebaker, 2009) and has become a mainstay of psychological therapy.

A particular problem for testing Freudian theories is that almost anything that conflicts with a prediction based in Freudian theory can be explained away in terms of the use of a defence mechanism. A man who expresses a lot of anger toward his father may be seen via Freudian theory to be experiencing the Oedipus complex, which includes conflict with the father, but a man who expresses no anger at all toward the father also may be seen as experiencing the Oedipus complex by repressing the anger. Because Freud hypothesized that either was possible but did not specify when repression would or would not occur, the theory is difficult to falsify.

In terms of the important role of the unconscious, Freud seems to have been at least in part correct. Research demonstrates that a large part of everyday behaviour is driven by processes that are outside our conscious awareness (Kihlstrom, 2008). Although our unconscious motivations influence every aspect of our learning and behaviour, Freud probably overestimated the extent to which these unconscious motivations are primarily sexual and aggressive.

Taken together, it is fair to say that Freudian theory is largely unfalsifiable; the id, ego, and superego, for example, are concepts that are difficult to define, observe, and measure. Freud’s ideas about the unconscious and its effects on human functioning are impossible to solidify into a set of rules for interpretation. Much of his theory has not been well supported by research; however, the fundamental ideas about personality that Freud proposed are nevertheless still major influences in popular culture, philosophy, art, film, and so on. Additionally, clinical psychologists frequently apply psychodynamic assumptions about the existence of an unconscious and the importance of early childhood in therapy. It is for these reasons that we still discuss Freudian approaches in the context of personality.

The Neo-Freudians

Freudian theory was so popular that it led to a number of followers, including many of Freud’s own students, who developed, modified, and expanded his theories. Taken together, these approaches are known as neo-Freudian theories. The neo-Freudians still think that early experiences are important in shaping who we are, but they’re more positive about the chances for adults to develop and change their personalities.

Alfred Adler

Alfred Adler (1870–1937) was a follower of Freud but he developed his own theory of personality. Adler proposed that the primary motivation in human personality was not sex or aggression but rather the striving for success and superiority. According to Adler, we create our unique lifestyle to achieve our life goals. For example, we may attempt to satisfy our need for success through our school or professional accomplishments. Adler believed that psychological disorders began in early childhood. He argued that children who were either overly nurtured or overly neglected by their parents were later likely to develop an inferiority complex, which is a psychological state in which people feel that they are not living up to expectations, leading them to have low self-esteem, with a tendency to try to overcompensate for the negative feelings. People with an inferiority complex often attempt to demonstrate their superiority to others at all costs. According to Adler, most psychological disorders result from misguided attempts to compensate for the inferiority complex in order to meet the goal of superiority. For Adler, the underlying motivation that guides successful personality is social interest. He said, “The happiness of mankind lies in working together, in living as if each individual had set himself the task of contributing to the common welfare” (Adler, 1964, p. 255).

Carl Jung

Carl Jung (1875–1961) was another student of Freud’s. Jung agreed with Freud about the power of the unconscious but felt that Freud overemphasised the importance of sexuality. Jung argued that in addition to the personal unconscious, there was also a collective unconscious, or a collection of shared ancestral memories. Jung believed that the collective unconscious contains a variety of archetypes, or cross-culturally universal symbols that explain the similarities among people in their emotional reactions to many stimuli (Jung, 1928). Important archetypes include the mother, the goddess, the hero, and the mandala or circle, which Jung believed symbolised a desire for wholeness or unity. For Jung, the underlying motivation that guides successful personality is self-realisation, which is learning about and developing the self to the fullest possible extent.

Karen Horney

Karen Horney (1855–1952) was a German physician who applied Freudian theories to create a personality theory that she thought was more balanced between men and women. Horney believed that parts of Freudian theory (e.g., penis envy) were biased against women. Horney argued that women’s sense of inferiority was not due to their lack of a penis but rather to their dependency on men, an approach that the culture made it difficult for them to break from (Horney, 1923/1967). For Horney, the underlying motivation that guides personality development is the desire for security — the ability to develop appropriate and supportive relationships with others.

Erich Fromm

Another important neo-Freudian was Erich Fromm (1900–1980). Fromm’s focus was on the negative impact of technology. According to Fromm, technology brings us independence, freedom, and power, but the use of technology makes us feel increasingly isolated from others. As we desire to become closer to others, we also create the need to escape from freedom that is brought by technology.

Erik Erikson

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) agreed with Freud about the psychosexual stages, but focused on the parent-child relationship and gave more importance to the role of the ego rather than the id. As you learned when you studied lifespan development, Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan, different from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life. In his theory, Erikson emphasised the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on sex. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which represents a conflict or developmental task (see Table PE.3). The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depend on the successful completion of each task.

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0-1 | Trust versus mistrust | Learns to trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 2-3 | Autonomy versus shame/doubt | Develops a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3-5 | Initiative versus guilt

|

Takes initiative on some activities; may develop guilt when success not met or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 6-11 | Industry versus inferiority

|

Develops self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12-18 | Identity versus confusion

|

Experiments with and develops identity and roles |

| 6 | 19-29 | Intimacy versus isolation

|

Establishes intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30-64 | Generativity versus stagnation

|

Contributes to society and becomes part of a family |

| 8 | 65- | Integrity versus despair

|

Assesses and makes sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Carl Rogers and the Self

Carl Rogers (1902–1987) was a humanistic psychologist. Like other humanistic psychologists, he emphasised the potential for good that exists within all people. One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self-concept, which refers to our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Parents can help their children achieve this by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. According to Rogers (1980), “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116). Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment. Rogers believed that people made their free choices, and he did think personality is “determined” by biology.

It’s important to note that psychodynamic and humanistic approaches share a common ground. While they prove valuable in psychotherapy, some of their ideas are hard to test and prove wrong. This lack of falsifiability can make it challenging to scientifically measure and confirm their assumptions. Now, shifting our focus to the next section, let’s delve into cognitive-behaviourist theories. Unlike the previous approaches, cognitive-behaviourism stands out for its emphasis on testable ideas and measurable concepts.

Image Attributions

Figure PE.4. Figure 14.14 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure PE.5. Figure 2 as found in Is the Influence of Freud Declining in Psychology and Psychiatry? A Bibliometric Analysis by Andy Wai Kan Yeung is licensed under a CC BY License.

Figure PE.6. Mother archetype by Rachel Lu is is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).