Chapter 16. Gender and Sexuality

Sexual Response and Romantic Love

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 21 minutes

Sexual Response

If you recall the ‘Circles of Sexuality’ or revisit them, you’ll notice the significant role of sensuality in our sexual experiences. Sensuality is intricately linked with intimacy, sexual identity, sexual health and reproduction, and sexualization. To understand sensuality’s role in sexuality, we’ll examine physiological responses while also considering the broader context. This approach helps us understand how various interconnected factors influence individuals’ interpretations of their physical and bodily experiences.

The changes to brain chemistry, the hormones that rush through the bloodstream, the sensory neurons behind that electric and tingling feeling of intimate touch, the role of erogenous zones in enhancing pleasure, and the pheromones that we broadcast that are picked up without conscious awareness by others all play a role in our sexual responses. Society, culture, and personal perspectives also shape our psychological interpretation of the physical changes during arousal and orgasm, influencing how we understand these experiences.

Sexual response is influenced by both biological factors, such as hormonal levels and neurological responses (Kruger, Giraldi, & Tenbergen, 2020; Rowland, 2006), and socialisation factors, including cultural norms and personal experiences (Hoyer & Velten, 2017; Alimohammadi, Zarei, & Mirghafourvand, 2017). Each individual person has a natural degree to which they become aroused in response to sexual stimuli, similar to how some people react more intensely to loud sounds or have a low to high pain tolerance (Basson, 2015).

Sexuality Response Cycle Explained

Sensuality begins with the enjoyment and pursuit of physical pleasure, involving the use of the senses to experience connection and gratification. In a sexual context, this involves touch, sight, smell, taste, and sound, each contributing to the overall sense of pleasure and connection.

Arousal marks the first phase of the sexual response. During this phase, there is an increase in sexual interest and excitement. Physiologically, changes include increased heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension. Individuals may experience various physiological reactions such as genital lubrication and swelling, erection of erectile tissues, and heightened sensitivity in erogenous zones. This phase also involves psychological arousal, characterized by heightened desire and anticipation.

Skin hunger plays a significant role in the Arousal phase. It refers to the deep emotional and physical longing for human touch. This craving for physical contact and connection can heighten the sensations experienced during arousal, making touch and physical closeness even more pleasurable and significant. Physical touch releases hormones such as oxytocin, which promote feelings of bonding and reduce stress, thereby enhancing the overall sexual experience.

As the individual transitions into the Plateau phase, sexual tension continues to build. The physiological changes initiated during arousal intensify. There is an increase in breathing rate, pulse, and blood pressure. The genital areas, including the clitoris, vaginal walls, and penis experience increased blood flow and sensitivity. Muscle contractions may begin rhythmically in the pelvic region, enhancing the sensation of sexual pleasure and preparing the body for orgasm.

The Orgasm phase is the climax of the sexual response cycle, characterized by peak pleasure and the release of sexual tension. During orgasm, individuals experience rapid contractions of the pelvic muscles. These contractions may lead to ejaculation in individuals with penises, while those with vaginas may experience contractions of the vaginal walls. The sensation of orgasm is often described as intense and euphoric, involving a complete release of built-up sexual tension.

Following orgasm, the body enters the Resolution phase, gradually returning to its normal state. Muscle tension, blood pressure, and heart rate decrease. Individuals may experience varying refractory periods; some may be able to achieve subsequent orgasms shortly after, while others may need more time. This phase brings a sense of relaxation and well-being as the body recovers from the heightened sexual state.

Throughout the entire sexual response cycle, stimulation of Erogenous Zones—areas of the body that are particularly sensitive to touch—plays a significant role. These zones vary widely among individuals and can include both genital and non-genital areas such as the neck, ears, inner thighs, and nipples. The stimulation of these zones can enhance arousal and contribute to the overall sexual experience.

While our biology sets the stage for sexual response, our personal and cultural experiences add another layer of complexity. Life experiences, including early sexual education, cultural background, and personal relationships, continually shape and modify our sexual responses over time (Bhugra & de Silva, 1993; Heinemann, Atallah, & Rosenbaum, 2016). Individual differences, such as varying levels of libido or sexual preferences, significantly impact how one perceives and desires to engage in different sexual behaviours (Baumeister, 2000). Social factors, such as the stigma or shame associated with certain sexual behaviours in different cultures, can profoundly affect how individuals perceive and experience touch and sexual contact (Polak et al., 2019).

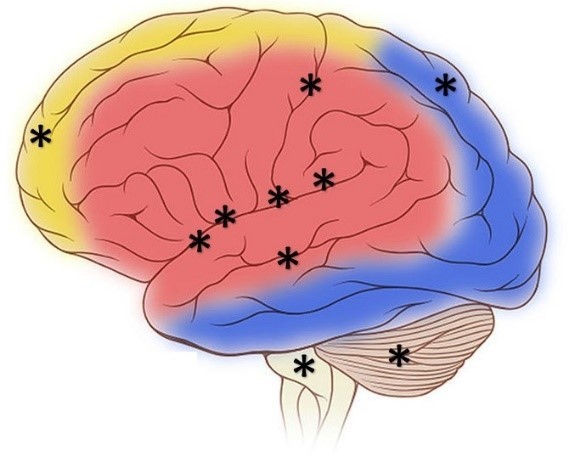

When we think about what parts of our body give us pleasure, we often think of the clitoris and penis first. But actually, our brain and nervous system play a much bigger role in feeling pleasure. Many parts of the brain are involved when we feel good. These include areas like the insula, temporal cortex, limbic system, nucleus accumbens, basal ganglia, superior parietal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum (Ortigue et al., 2007).

Studies using brain imaging have shown that these brain areas are active not just when the skin is touched, but also during orgasms that happen without any touch (Fadul et al., 2005) and when people touch their own erogenous zones (Komisaruk et al., 2011). Erogenous zones are parts of the skin that are especially sensitive to touch and are connected to the somatosensory cortex in the brain (described next section), which is the part that processes touch.

Love and Heartbreak: Biochemistry

Love is deeply biological. Have you ever considered why we feel such intense happiness when we’re in love? Love is a complex emotion influenced by our brain’s biology. It involves feelings of trust, belief, pleasure and reward, and is affected by brain chemicals like oxytocin, vasopressin, dopamine and serotonin (Esch & Stefano, 2005). Recent scientific research has begun to provide a physiological explanation for love. Romantic love activates the brain’s limbic structures, which are also involved in managing fear, anxiety and other neurotransmitter changes (Marazziti, Palermo, & Mucci, 2021). The brain “in love” is flooded with sensations, often transmitted by the vagus nerve, and creating much of what we experience as emotion. The modern cortex struggles to interpret love’s messages, and weaves a story (narrative) around incoming skin and body (visceral) experiences, potentially reacting to that story rather than to the physical reality.

Love touches every part of our lives and has inspired many pieces of art. It also deeply affects how we think and feel, both in our minds and bodies (Marazziti, Palermo, & Mucci, 2021). Have you ever wondered why a breakup feels physically painful? Consider a friend who has just gone through a tough breakup. What might be happening in their brain to cause such deep emotional and physical pain? A “broken heart” or a failed relationship can have disastrous effects; bereavement disrupts human physiology and may even lead to death (Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). Without loving relationships, humans fail to flourish, even if all of their other basic needs are met (Friedman, 1993). As such, love is clearly not “just” an emotion; it is a biological process that is both dynamic and vital on several dimensions (Esch & Stefano, 2005). Social interactions between individuals, for example, trigger cognitive and physiological processes that influence emotional and mental states. In turn, these changes influence future social interactions. Similarly, the maintenance of loving relationships requires constant feedback through sensory and cognitive systems; the body seeks love and responds constantly to interactions with loved ones or to the absence of such interactions. Now, let’s examine how oxytocin, a key love hormone, influences our relationships (Campbell, 2008).

Oxytocin’s Influence in Human Relationships

Why do you think a simple hug can make us feel better? Oxytocin, often referred to as the “love hormone” plays a significant role in social bonding and trust in both romantic and platonic relationships. The hormone oxytocin is produced in the hypothalamus. Oxytocin fosters trust and affection, essential in both romantic and platonic relationships (Ramalheira & Conde Moreno, 2022). In romantic contexts, higher oxytocin levels are linked to stronger feelings of love and a greater appreciation of a partner’s supportive actions (Algoe, Kurtz, & Grewen, 2017). Interestingly, oxytocin’s role extends beyond human interactions, as it also strengthens the bond between humans and animals, like dogs (MacLean & Hare, 2015). Think about a time when you felt a strong bond with a pet. How might oxytocin have played a role in forming this connection?

Watch this video: The science of falling in love – Shannon Odell (6.5 minutes)

“The science of falling in love – Shannon Odell” video by TED-Ed is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

It’s clear that our sexual experiences are shaped by both our biology and our social environment. Just like we all react differently to things like loud noises or pain, we also have our own unique ways of experiencing sexual feelings. These experiences are influenced by our life’s journey and can change over time.

We’ve learned that sexual response isn’t just about our bodies reacting; it’s also about how we think and feel about these reactions. Our brains play a huge role in this. They process the sensations from our skin and can make us feel pleasure. We’ve seen that areas like the lips have a big part of the brain, the somatosensory cortex, dedicated to them. This means they can give us strong feelings of pleasure.

Remember, the way we understand and interpret these feelings can be affected by our society and culture. What we think is normal or acceptable can change how we feel about our own sexual responses. It’s important to keep an open mind and understand that everyone’s experience is unique.

Sexual response, at its core, is our body’s celebration of pleasure, joy, excitement and fun. It’s a dance of sensations and emotions that can elevate our experiences to new heights of happiness and fulfilment. This kind of ecstatic enjoyment is deeply rooted in mutual, respectful and consensual relationships. It thrives in an environment where vulnerability is embraced, intimacy is shared, and communication is open and honest. In such a setting, sexual response becomes more than just a physical reaction; it can facilitate connection to self (during masturbation) or another during sexual activity. This joyous exploration of sexuality in relationships founded in trust and respect, not only enhances our physical pleasure but also strengthens our emotional bonds, enriching our lives with a deeper sense of satisfaction and happiness.

Summary for Introduction to Sexuality

Introduction to Sexuality, explores human sexuality, starting with the “Circles of Sexuality”. This model breaks down sexuality into six distinct areas: Sensuality, Intimacy, Sexual Identity, Sexual Health and Reproduction, Sexualization, and Values. Each circle represents a crucial aspect of sexuality, from the personal acceptance and enjoyment of one’s body (Sensuality) to the beliefs and moral standards that shape our attitudes towards sexuality (Values). This comprehensive framework encourages a holistic understanding of sexuality, emphasising the importance of awareness, acceptance and ethical considerations in sexual behaviours and attitudes.

The section on Sexual Orientation expands the discussion by exploring various identities, including queer (homosexual), straight (heterosexual), bisexual, pansexual, polyamorous and asexual. It explains the wide diversity in the sexuality galaxy and highlights the diversity within sexual orientation and the significance of understanding and respecting this diversity.

“Our Sexual Development” explores sexual development across different life stages, from infancy to adolescence.The role of puberty-delaying hormone blockers for transgender individuals is also discussed. This part provides a scientific and compassionate overview of sexual development, emphasising the diversity of experiences and the importance of understanding and supporting individuals through their developmental journeys.

Anatomical Sex Differentiation examines the biological and genetic factors that contribute to sex development, including intersex anatomy. It provides a scientific basis for understanding the commonalities and differences between female and male reproductive anatomy, supported by videos that offer further insights into sex determination and differentiation.

We explore the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual response and the importance of touch, or “skin hunger”, in our emotional and physical well-being. It discusses how sensuality, arousal, orgasm and resolution are integral parts of the sexual experience, influenced by both biological factors and social contexts. The role of erogenous zones and the brain in sexual pleasure is examined, highlighting how our sexual responses are deeply interconnected with our perceptions and societal influences.

Finally, we discuss how love is a complex emotion deeply rooted in our biology, influenced by brain chemicals like oxytocin, vasopressin, dopamine, and serotonin. Romantic love activates the brain’s limbic structures, creating intense emotional experiences. This biological process explains why love brings happiness and why a breakup can cause deep emotional and physical pain, sometimes described as a “broken heart.” Oxytocin, known as the “love hormone,” plays a significant role in social bonding and trust, enhancing feelings of love and connection in both romantic and platonic relationships. It also strengthens bonds between humans and animals. Understanding the biochemistry of love underscores its profound impact on our mental and physical health, highlighting its vital role in human relationships.

As we conclude this section, it’s clear that the study of sexuality is not just an academic pursuit but a deeply personal journey that touches on every aspect of our being at every age. The knowledge gained here serves as a foundation for further exploration, understanding and acceptance of the diverse expressions of human sexuality. In what ways might exploring your own sexual identity and preferences contribute to your personal growth and well-being? How can you support and advocate for the rights and well-being of individuals with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities in your community? For those eager to delve deeper into these topics, the journey doesn’t end here. The field of sexuality is ever-evolving, with new research, perspectives, and narratives emerging that continue to enrich our understanding and appreciation of this fundamental aspect of human life.

Image Attributions

Figure GS.6. This image was adapted by UPEI Introduction to Psychology 1 by adding identifying marks to an image by Frank Gaillard which is licensed under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).