Chapter 16. Gender and Sexuality

Some Foundational Issues

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 42 minutes

Dr J’s Story: My Sex Education Training and How that Changed Me as a Teacher

When I was in my third year of undergraduate psychology studies, I began volunteering at Planned Parenthood. My role primarily involved teaching youth and young adults about various contraception methods, including ways to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Professional nurses trained me to educate clients on using condoms, diaphragms, IUDs (intrauterine devices), hormonal implants, and birth control pills, and to discuss menstruation, pregnancy, and abortion. My mentors stressed the importance of creating a compassionate and welcoming learning environment. They guided me in delivering detailed, accurate information about reproductive anatomy, sexual activity, and the mechanics and biochemistry of each contraception method. I was taught to discuss sex with individuals and small groups without embarrassment and with good humour. I learned the correct scientific terms for sexual anatomy and different sexual behaviours. I learned to welcome and celebrate people of all gender identities and sexual orientations and to speak joyfully and freely about sexual pleasure and health.

My mentors taught me another crucial skill: how to set aside my personal values and focus on highlighting the clients’ values. Honestly, sometimes my choices and values differed from those of the clients visiting the clinic. My values, however, were meant to guide me, not the clients. I learned that validating and working with the clients’ values was the most important thing I could do to empower them and increase their likelihood of adopting healthy sexual behaviours. In this chapter, I will be inviting you to reflect on your values and compare those with the values of another person. Will you find it challenging or easy to acknowledge your values and, at the same time, focus on and work within the ethics of the other person’s values?

I was fortunate to be mentored by the renowned Meg Hickling, an extraordinary person who taught sex education classes in many elementary and high schools across British Columbia for decades. I observed Meg teaching at the clinic, in Grade 3 classes, and at school assemblies. She was kind, compassionate, fun, and always smiled and joked during her lessons. I was so inspired by Meg that I modelled my university lecture teaching style after her straightforward, joyous, heartfelt approach (see Supplement GS.1 to watch Meg speak). Her consistent message was that people, especially young children, need to understand the science of how their bodies work to make informed choices.

My volunteer work at Planned Parenthood was the perfect outlet for sharing my passion for biology and my desire to be of service to others. Surprisingly, I loved teaching about sexual health, reproduction, and contraception so much that I volunteered for weekly shifts and stayed for five years, and later, after earning my Ph.D., continued teaching the Psychology of Gender for 20 more years.

What made teaching at this clinic so special? The clients were seeking a safe place to learn evidence-based information in plain language, free from judgement or shame. Initially, some clients were shy or embarrassed. But soon, they relaxed and felt comfortable asking very private questions about sexual anatomy, sexual activity, and how to choose the most suitable contraceptive method for them.

Here are my takeaways from those sex education days. Everyone I met in those settings:

- Had a human body with human needs and vulnerabilities.

- Had a right to know all about their bodies, including how to experience sensual/sexual pleasure and how to stay safe and healthy.

- Had questions they were too shy to ask about and often showed relief, and sometimes even laughter, when they received the much-needed information.

- Felt empowered by the sex education and health information, and sometimes even taught what they learned to others.

- Sought validation, respect, close physical contact — and love.

Writing this chapter about gender and sexuality has revived many fond memories of my time at Planned Parenthood. For this chapter, I have drawn upon those same essential skills I learned in my sex education training.

During my time at Planned Parenthood, I learned the importance of accurate information and consent in sexual health education. It’s crucial to both provide correct information and respect each person’s right to make informed decisions about their body and relationships. This highlights two key principles in discussions about gender and sexuality: being informed and understanding consent.

Informed

Staying informed about gender and sexuality is not simple. These topics are constantly evolving with new research and changing societal perspectives. In this chapter, we explore gender and sexuality in order to provide a foundational understanding of these complex subjects. The science and social realities surrounding gender and sexuality change rapidly, necessitating frequent updates. Each year, outdated language needs to be replaced with new terminology to remain relevant and respectful to all. Of all the topics I have taught in my career, the subjects of gender and sexuality require the most reading, research, and fact-checking to stay current. For example, while other psychology courses might need updating every 3-5 years, the content on gender and sexuality requires significant updates every year. This chapter, therefore, is designed to equip you with the knowledge to understand the current evidence-based science and psychological theories about gender and sexuality, and to encourage you to continue updating your knowledge going forward.

Consent

Before we learn the science and theories about gender or sexuality, let’s begin with a discussion about consent, as it is the foundation of all respectful and healthy interactions. In short, discussing consent first establishes a responsible and respectful context for the rest of the chapter.

Understanding consent is a fundamental aspect of not only psychology, but all relationships and interactions. Consent is an agreement to participate in an activity. It’s about saying a clear, enthusiastic ‘yes’ to being involved in something, especially in intimate contexts. Remember, consent isn’t just a one-time question; it’s an ongoing conversation, flexible and subject to change at any point. It is vital to recognize situations where consent cannot be given. This includes when a person is underage, uncommunicative (cannot speak or is not capable of understanding the question), unconscious, or under the influence of substances.

Consent: more than just “no” means “no”

Consent goes beyond a simple “yes” or “no.” It is about the dynamics of human behaviour and communication. When consent is obtained through pressure or coercion, it’s not considered genuine. We need to remember that power dynamics within relationships play a large role in our ability to obtain consent. The concept of agency, referring to each person’s ability to make independent choices about their body and actions, is also intertwined with consent. Agency is an individual’s legal and practical capacity to make independent decisions free from coercion. Consent is more than a legal requirement; it is an everyday practice rooted in respect and empathy.

Consent needs time and patience

Understanding consent also involves recognising that our responses to sexual advances may not always be immediately knowable. Sometimes, it takes a moment to truly understand what we want. This is where the concept of interoception comes into play. Interoception is our ability to sense and interpret the signals our body is sending us. It’s about tuning into our inner feelings to determine whether we’re feeling a definite “yes”, an uncertain “maybe”, or a clear “no”. You may recall that interoception relies on sending messages about internal organs through unmyelinated nerves. These nerves, without myelin wrapping, are deeply interconnected with other nerves. Signals from unmyelinated nerves take a slower pathway, requiring more time to reach consciousness than signals from myelin-wrapped nerves. This process requires time and space to connect with our own physical and emotional responses, therefore it’s essential to allow adequate time for consent. Consent must also be seen as reversible; if upon deeper reflection we realise that we feel a “no” after an initial “yes”, this change of heart must be respected. More than that, in the context of enjoyable and loving sex, consent should be a continuous negotiation. We must stay aware of our body’s moment-to-moment messages, allowing space in our relationships to request changes or stop sexual activity as desired. Consent is not just a momentary agreement but an ongoing, responsive physical and emotional conversation with ourselves and others.

The psychology of consent

How do we decide if we should say “yes” or “no” to something someone offers us? There are several skills involved with the psychology of consent, that you should know and practice before you make your decision:

- Knowing yourself — What you’re okay with, what you’re not, and what matters to you.

- Being informed — Do you have science-based or other reliable information you need to make your decision?

- Feeling no pressure — Are you feeling pressured to make this decision?

- Making an educated guess about your reaction — What is your best prediction of how you will respond or react?

- Knowing the extent to which you can back out — Can you change your mind if you start to have a negative experience?

Table GS.1 (below) can help us practice applying these skills. Let’s start by imagining two different hypothetical examples:

- Example #1 Peanut Butter – Someone offers you a spoonful of peanut butter to taste, which carries a small risk of an allergic reaction. You can stop tasting it at any time.

- Example #2 Hellevator ride – Someone invites you to ride the “Hellevator”, a scream-worthy, sheer drop amusement park ride in Vancouver. It has no known allergy risks. Some people find it terrifying, and some, thrilling. The ride cannot be stopped once it starts (except in case of emergency).

Note: for these two hypothetical examples let’s pretend that you have never tried peanut butter or ridden the Hellevator ride, so you cannot rely on any past experiences to inform your decisions in these examples.

| Aspect of Consent | Explanation | General Examples | Peanut Butter Example | Hellevator Ride Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self Knowledge | Understanding your own values, preferences, boundaries, health status, cultural or religious beliefs, and family history. | Deciding not to participate in an activity that conflicts with your personal values, health conditions, etc. | Considering whether trying peanut butter aligns with your dietary preferences or restrictions.(e.g., have you ever tried and liked other nut butters?) | Reflecting on your personal limits and excitement for thrill-seeking activities before deciding to board the Hellevator. |

| Facts and Side Effects | Being informed about what is being offered to you, including any known side effects and the source’s safety. | Choosing a prescribed medication over a street drug because the street drug may have unknown or dangerous additives. | Researching peanut allergies and potential reactions before deciding to try (remember in this hypothetical example you have never tried peanut butter before). | Investigating the Hellevator’s safety record and design to assess risks before you decide to take the plunge. |

| No Pressure | Feeling free from external pressures to consent. | Declining a drink at a party despite peer pressure, prioritising your personal comfort and safety. | Choosing to try or not try peanut butter based on your personal interest, not because of others’ encouragement. | Deciding independently, without succumbing to peer pressure, whether to face the Hellevator. |

| Your Best Guess | Anticipating and predicting how you might respond to an experience, including potential biological, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual reactions. | Predicting that trying a new sport might be challenging but ultimately rewarding, based on your past experiences and your personal resilience. | Speculating on whether peanut butter will last will be good or bad, or if you might have an allergic reaction. | Estimating your emotional readiness and excitement versus fear for the Hellevator. |

| Backing Out | Knowing what the options are for you to stop the activity to withdraw consent if the experience is not as expected or is negative. | Stopping participation in a study or trial if it becomes uncomfortable or distressing. | Knowing you can start by taking a small taste of peanut butter and if you don’t like it you can stop. If you have a rare allergic reaction you can get medical help. | Knowing that you can exit the Hellevator queue anytime before the ride starts but once it starts you cannot back out. |

Planned Parenthood has created the helpful mnemonic “FRIES” to summarise the steps involved in consent.

Consent “FRIES”

Consent is a crucial concept in all our interactions, ensuring that everyone feels safe, respected, and understood. Another way to make understanding consent easier, we can use the acronym “FRIES” (Planned Parenthood, 2022). This simple yet powerful guide breaks down the essential elements of consent into five key points: Freely Given, Reversible, Informed, Enthusiastic, and Specific. Each aspect highlights a different part of what it means to truly agree to something. By keeping these principles in mind, we can all contribute to healthier, more respectful relationships and interactions.

- Freely Given: Consent must be given without any pressure, force, or manipulation. It means everyone involved agrees by their own choice.

- Reversible: Anyone can change their mind at any time. Just because someone agreed before doesn’t mean they have to keep agreeing.

- Informed: Everyone must fully understand what they are agreeing to. This means having all the necessary information before making a decision.

- Enthusiastic: Consent should be given with excitement and eagerness. It’s not just the absence of a “no” but the presence of a clear “yes”.

- Specific: Consent is for a specific action at a specific time. Agreeing to one thing doesn’t mean agreeing to others.

Understanding these points helps to ensure that all interactions are respectful and comfortable for everyone involved.

In the following videos, we further explore the concept of consent in a way that is clear, straightforward, and relevant to real-world situations. In the first video, “Let’s Talk About Consent”, we look at consent in different contexts. How do we recognise when consent is not given, especially in situations where coercion or pressure might come into play? We explore the dynamics of saying “yes” or “no”, understanding that consent is not just about the words spoken, but also about the freedom and capacity to make those choices. In the second video, we will look at the “consent is like tea” analogy, which provides an accessible introduction to the idea that consent must be freely given and can be withdrawn at any time.

Watch this video: Let’s Talk About Consent (4 minutes)

“Let’s Talk About Consent” video by hashtagNYU is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Watch this video: Tea Consent (Clean) (3 minutes)

“Tea Consent (Clean)” video by Blue Seat Studios is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Through these discussions, we aim to empower you with a finely detailed understanding of consent. This knowledge equips you to navigate relationships with respect, empathy and awareness. Consent is about more than just avoiding harm; it’s about fostering healthy, positive interactions based on mutual respect and understanding.

Now, before we can explore gender and sexuality in more detail, we need to address the error of thinking about these concepts in terms of strict binaries or continuums.

Important Maths Lesson: Learning about Binary, Continuum, and Sliding Scale Models: The Juice Bar Survey

Before we can talk more about gender and sexuality, I need to explain some math concepts to you. Don’t worry though, because I will make this math lesson simple and fun. Our lesson begins with a hypothetical, popular juice bar. I will explain these math concepts using the examples of customers’ taste preferences at a juice bar.

(Note: we need to agree at the beginning that, when we move from discussing this juice bar example to gender and sexuality, we will be careful not to infer that these important aspects of our humanity are a matter of preference. In this chapter, we will discover that, far from being a matter of preference, what determines our gender and sexuality is complex, different for each individual, and still not yet fully understood by psychologists and medical professionals.)

Imagine that there is a local juice bar in your neighbourhood so popular that there are line-ups going out the door on weekends as people wait to buy this award-winning juice. The juice bar chef’s secret is a perfect blend of fresh pressed apple mixed with freshly-squeezed orange juice. This secret juice recipe is the base for all the wonderful fruit and veggie juice blends on the menu. The customers all agree that the flavours of the apple and orange juice bring out the best in each other — the blended juice is neither too tart nor too plain. No matter how many other fruits are added, the customers know that all the juice smoothies on the menu will be a success if they are based on the fresh apple and orange juice blend.

Now imagine the juice bar chef is thinking of expanding the menu. A psychologist has been hired to conduct a survey of the customers’ fruit preferences. Her job is to survey all the regular customers in the line-up and ask them to rate their preferences for fruit. Our job will be to judge the effectiveness of each of the survey designs. We need to see which survey best captures the complete story of the fruit preferences for these thirsty customers. Are you ready? Let’s begin.

The first survey the psychologist designs is simple. There are two checkboxes. Each customer will check one of the boxes.

Forced Choice/ Binary Model

Which fruit do you prefer? (You must check ONE)

[ ] apples

[ ] oranges

In psychology, we might call this kind of question a forced choice or a binary decision. How well do you think this “apple or orange” survey will measure the customers’ fruit preferences? This straightforward survey is met with discontent from the line of customers because many found it challenging to choose between apples and oranges, since they enjoyed both flavours equally. This dilemma among the patrons revealed a significant limitation in the survey’s design, failing to account for those who favoured the blend of both fruits in their juice.

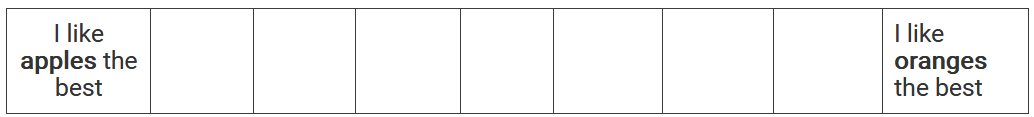

After listening carefully to the feedback about the survey design, the psychologist designs a new survey based on a continuum. This time she writes the question: “Please place a mark on this continuum that best describes your fruit preference. On one end of the scale is ‘I really like apples the best’ and on the other end of the scale is ‘I really like oranges the best.”

Continuum Model

By allowing customers to show their preference for a blend of apple and orange juices, this continuum improves upon her previous, more limited forced-choice/binary survey. While you observe customers filling out this new continuum-style survey, you notice they struggle because they really like both apples and oranges. Unfortunately, the psychologist’s apple/orange continuum forces them to choose whether they like apple juice more than orange juice or orange juice more than apple juice. In addition, the middle of the apple to orange continuum is a neutral zone — neither apple nor orange. These customers have no way to rate their passion for both apple and orange juices — indicating they like both equally or to say they dislike both apples and oranges. As a result, you ask the psychologist to rewrite the survey.

Responding to earlier concerns, the psychologist’s new continuum-based survey initially seemed more accommodating, allowing customers to express a more specific preference for apple or orange juice. However, as they interacted with this model, a new issue emerged. While the continuum allowed for a more graduated expression of preference, it still compelled customers to lean towards one fruit over the other. This constraint was particularly problematic for those who cherished the unique blend of both apple and orange flavors equally.

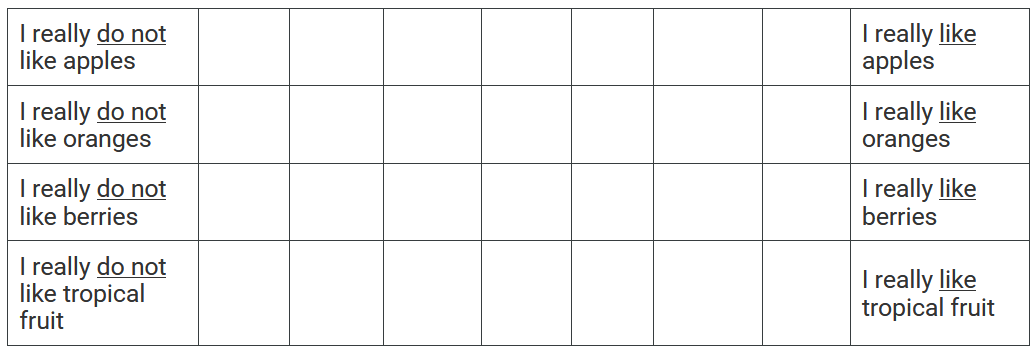

Several Sliding Scales Model

Taking your feedback, the psychologist comes back with a new survey form. This time she has created sliding scales, one for each kind of fruit offered at the juice bar. Customers in the line-up can now rate their preferences from not eh one end of the scale “I really do not like this fruit” to the other end of the scale: “I really like this fruit”. There is a sliding scale for apples and another for oranges, and she has even added two extra sliding scales for berries and tropical fruits. How easy or hard will it be for the sliding scales to capture the customers’ true fruit preferences?

Customers found this method more reflective of their actual preferences, as they were no longer constrained to choose between apples and oranges, but could instead rate their affection for each fruit separately. This was particularly beneficial for those who had previously struggled with the forced choice and continuum models, as they could now acknowledge their equal appreciation for both apple and orange juices, as well as other fruits.

After carefully considering the feedback on the previous surveys, the psychologist evolved her approach to better capture the precise preferences of the juice bar’s customers. Moving away from the restrictive binary and continuum models, she introduced a new survey form featuring several sliding scales — one for each fruit. This innovative method allowed customers to express their individual preferences for apples, oranges, berries and tropical fruits without compromising or restricting their response.

The metaphor of the fruit juice bar and its various survey methods offers us a way to understand the limitations of binary and continuum models in capturing complex other human values and attitudes such as those related to gender identity and sexual orientation. Let’s extend this maths metaphor to understand these concepts better.

Binary Model (Forced-Choice)

In the binary model, like the first survey with only two options (apple or orange), individuals are forced to choose between two distinct categories. This is akin to traditional views on gender (female OR male) and sexual orientation (queer (homosexual) OR straight (heterosexual). However, this binary model fails to represent those who identify with aspects of both categories or neither. Just as some juice bar customers might like a blend of apple and orange, many individuals find that a simple binary choice doesn’t fully represent their complex experience of gender and sexuality. When was the last time you were torn because you had to make a choice but neither option fully suited you?

Continuum Model

The continuum model, represented by the second survey, offers a scale (like apple to orange), suggesting a fluid range between two alternatives. In the case of gender a range from female to male. In the case of sexual orientation a range from queer (homosexual) to straight (heterosexual). More inclusive than the binary model, this approach acknowledges that people can experience a mix of these identities. However, it still implies a linear progression from one identity to another and centres on a neutral midpoint, which might not accurately reflect the intensity of an individual’s identification with multiple aspects and both ends of the scale simultaneously. In gender and sexuality terms, this model suggests a single line, step-by-step progression from, say, female to male or homosexual to heterosexual, which oversimplifies the diversity of gender identity and sexual orientation experiences. Think of a subject that you are interested in. Now imagine writing one continuum scale where you could rate your liking for your favourite subject, say football on one end and hockey on the other end of the scale. Do you think a single line is enough to capture all the aspects of what you like about these two subjects? Why or why not?

The Kinsey Scale compared to Vrangalova and Savin-Williams (2012)

Some key work on sexuality was conducted in the 1940s and 1950s by the biologist Alfred Kinsey. Alfred Kinsey pioneered research in human sexuality through thousands of interviews and the development of “The Kinsey Scale” of human sexual preferences. The Kinsey Scale is a 7-point metric that categorises individuals from 0 (exclusively heterosexual) to 6 (exclusively homosexual), and includes the midpoint 3 (equally homosexual and heterosexual). What do you think about Kinsey’s scale?

Vrangalova and Savin-Williams (2012) found evidence for five different categories of sexual orientation which they described on the following continuum:

Heteosexual – Mostly Heterosexual – Bisexual – Mostly Gay/Lesbian – Gay/Lesbian

Does this continuum seem like an improvement over the Kinsey Scale? Why or why not? What would not fit on these two continuum scales?

Several Sliding Scales Model

The several sliding scales model, like the juice bar psychologist’s third survey with separate scales for different fruits, allows for a more individualised expression of preferences. In the context of our juice bar, the several sliding scales model is like giving customers the freedom to fully express their preference for each fruit individually. Just as they can rate their enjoyment of apples, oranges, berries and tropical fruits separately, this model allows individuals to recognise and express the diverse aspects of their gender identity (e.g., female, intersex, male, gender-non binary, neutrois, gender fluid — see Table GS.2. Gender Identification: Several sliding scales model) and sexual orientation (same-gender sexual attraction, different-gender sexual attraction, or no sexual attraction, etc. — see Table GS.3. Sexual Identification and Behaviours: Several sliding scales model) without being confined to a single choice or a continuum. If you were to create a set of sliding scales for your own interests and personality traits, what would some of those scales represent? How does this idea help you to understand the benefits of the several sliding scales model in capturing the diversity of human identity?

Now that we have examined the measurement issues involved in designing the juice bar surveys, let’s reflect on how our assumptions are revealed in the questions we ask and the survey design choices we make.

Assumptions at the Juice Bar

Our hard-working psychologist is well-prepared with clipboards and surveys, ready to uncover the juice bar customers’ fruit preferences. Did you notice that there are assumptions in each of the psychologist’s survey designs? At first, when our psychologist asks customers to use the forced-choice survey, it is as though she was saying, “You must choose to be a team apple or team orange fan, with no middle ground.” This kind of questioning — apples or oranges — reveals that the psychologist may have the assumption that folks can’t possibly like both apples and oranges equally. In terms of gender this would be like assuming everyone must fit neatly into “female” or “male” boxes, with no room for a blend of both or a rejection of both. Or it is like assuming that everyone must fit neatly into queer or “straight” boxes in sexual orientation, with no room for a blend of both.

The assumption in the continuum survey, gently hints that if you’re starting to prefer apples, you must be starting to dislike oranges. Extending this assumption to gender, it is as if the more you identify with masculinity, the less you must feel feminine, or vice versa. In terms of sexual orientation, the more you identify as homosexual, the less you must identify as heterosexual, or vice versa. The continuum model does not allow that a person to like one aspect without starting to downgrade their liking for the other aspect on the continuum.

Finally, our psychologist has an “aha” moment and rolls out the many sliding scales survey. This approach celebrates the idea that loving apples doesn’t dim your passion for oranges, berries or even those exotic tropical fruits. Each preference is independent and equally valid. This mirrors the understanding that someone’s gender identity or sexual orientation isn’t a trade-off between fixed categories. Instead, it’s a spectrum of diverse and independent experiences, where you can embrace multiple identities simultaneously, just like savouring a fruit salad with all your favourite flavours! 🍎🍊🍓🥭

Conclusion

The many sliding scales model, therefore, offers a more inclusive and accurate representation of the complex and intertwined nature of gender identity and sexual orientation. This model recognises that these aspects of identity are not mutually exclusive (continuum) or fixed (forced choice/binary) but can be experienced in varying degrees and combinations. This approach respects the individuality of each person’s experience, much like acknowledging each customer’s unique fruit juice preferences at the juice bar. By moving beyond binary and continuum models, we can embrace a more holistic understanding of human identity, one that celebrates diversity and complexity.

Our important maths lesson about the binary, continuum, and sliding scale survey models from our juice bar example have highlighted the diverse and complex nature of individual preferences and choices. We also learned about the importance of knowing the psychology of concept of consent. It is a crucial practice in our discussions about sexuality and gender. It emphasises the need to recognise and respect each person’s unique choices and personal boundaries. The juice bar surveys served as a metaphor for the variety of preferences people have.

As a final reminder, it’s important that we remember that gender and sexuality are essential, complex, foundational parts of our identity. Unlike choosing between apples and oranges in our juice bar example, gender and sexuality are not about what we prefer. This chapter will show us that the factors influencing our gender and sexuality are complex, formative, change over the lifespan, vary from person to person and are not yet completely understood by psychologists and medical experts.

Let’s set the tone of this chapter on gender and sexuality in a powerful and brave way, by listening to transgender poet and activist, Alok Vaid-Menon.

“… I heard a story once

about people who had

the audacity to

love even in the face of

profound grief and

despair.

I think I think those people

were called humans.”

Watch this video: “I think those people are called humans…” (1 minute)

Image Attributions

Figure GS.1. Photo by Polina Tankilevitch is licensed under the Pexels license.

Figure GS.2. Photo by cottonbro studio is licensed under the Pexels license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).