Chapter 14. Personality

Traits, Temperaments, and Heritability

Amelia Liangzi Shi

Approximate reading time: 25 minutes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Contrast Big Five, 16 Personality Factors, and the Eysenck’s extroversion-stability model.

- Acknowledge the power of biological inheritance on personality

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood with a set of basic traits. Personality traits reflect people’s characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Personality traits imply consistency and stability; for example, someone who scores high on extraversion is expected to be sociable in different situations and over time. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? Moody or even-tempered? These personality traits reflect basic dimensions on which people differ. According to trait psychologists, there are a limited number of these dimensions — dimensions like extraversion, conscientiousness, or agreeableness — and each individual falls somewhere on each dimension, meaning that they could be low, medium, or high on any specific trait.

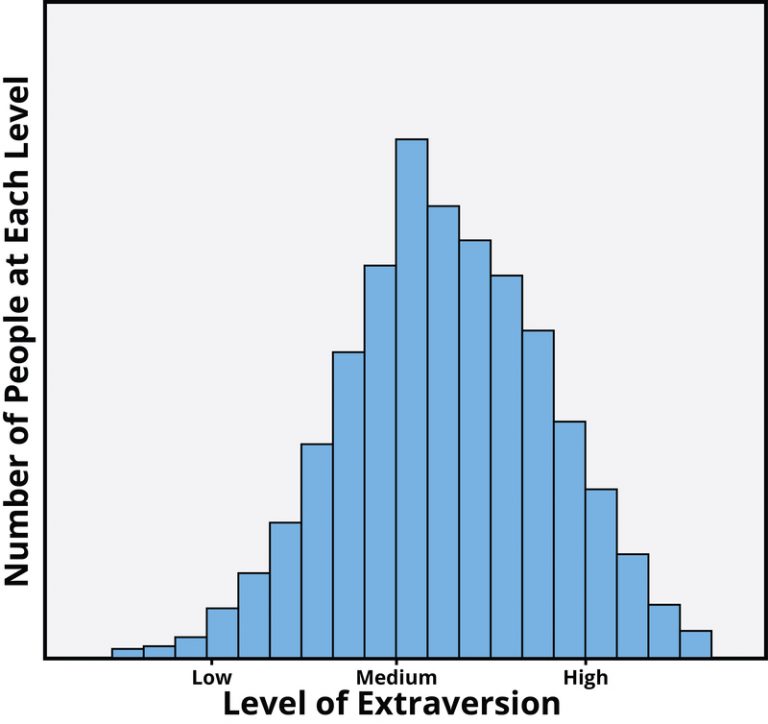

An important feature of personality traits is that they reflect continuous distributions rather than distinct personality types. This means that when personality psychologists talk about introverts and extraverts, they are not really talking about two distinct types of people who are completely and qualitatively different from one another. Instead, they are talking about people who score relatively low or relatively high along a continuous distribution (i.e., a continuum). In fact, when personality psychologists measure traits like extraversion, they typically find that most people score somewhere in the middle, with smaller numbers showing more extreme levels. From a survey of thousands of people, the distribution of extraversion scores indicates that most people report being moderately, but not extremely, extraverted, with fewer people reporting very high or very low scores.

Early trait theorists tried to describe all human personality traits. For example, one trait theorist, Gordon Allport (Allport & Odbert, 1936), found 4,500 words in the English language that could describe people. He organised these personality traits into three categories: cardinal traits, central traits, and secondary traits. A cardinal trait is one that dominates your entire personality, and hence your life, such as Mother Theresa’s altruism and Ebenezer Scrooge’s greed. Cardinal traits are not very common: few people have personalities dominated by a single trait. Instead, our personalities typically are composed of multiple central traits. Central traits are those that make up our personalities, such as loyal, kind, agreeable, friendly, sneaky, wild, and grouchy. Secondary traits are those that are not quite as obvious or as consistent as central traits. They are present under specific circumstances and include preferences and attitudes. For example, one person gets angry when people try to tickle them; another can only sleep on the left side of the bed; and yet another always orders their salad dressing on the side. And you — although not normally an anxious person — feel nervous before making a speech in front of your English class.

The 16 Personality Factors

In an effort to make the list of traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell (1957) identified 16 factors or dimensions of personality:

- warmth,

- reasoning,

- emotional stability,

- dominance,

- liveliness,

- rule-consciousness,

- social boldness,

- sensitivity,

- vigilance,

- abstractedness,

- privateness,

- apprehension,

- openness to change,

- self-reliance,

- perfectionism, and

- tension.

He developed a personality assessment based on these 16 factors, called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting. Take this assessment based on Cattell’s 16PF, to see which traits may dominate your personality.

Temperament: Extroversion-Stability Model

Psychologists Hans and Sybil Eysenck focused on temperament, the inborn, genetically-based personality differences. The Eysencks (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1963) viewed people as having two specific personality dimensions: extroversion/introversion and neuroticism/stability. They believed personality is largely governed by biology.

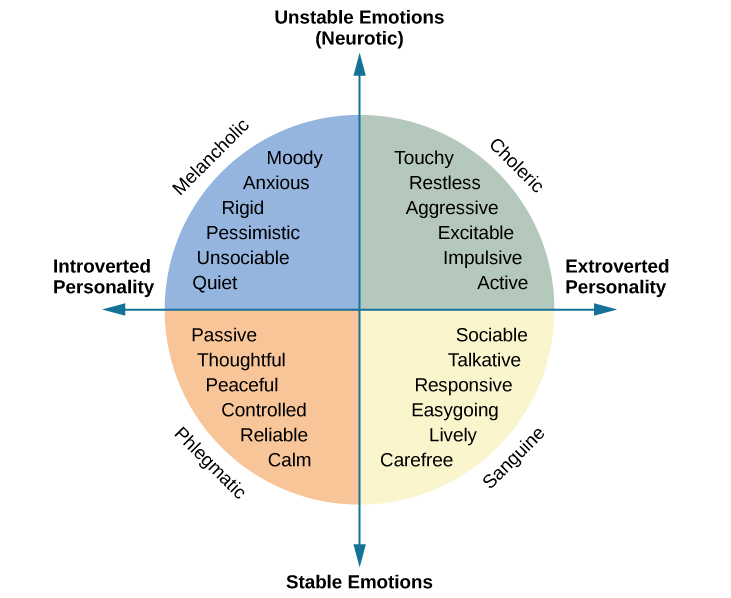

According to their theory, people high on the trait of extroversion are sociable and outgoing, and readily connect with others. By contrast, people high on introversion experienced too much sensory stimulation and arousal, which made them want to seek out quiet settings, engage in solitary behaviours, and limit their interactions with others. In the neuroticism/stability dimension, people high on neuroticism tend to be anxious; they tend to have an overactive sympathetic nervous system and, even with low stress, their bodies and emotional state tend to go into a flight-or-fight reaction. In contrast, people high on stability tend to need more stimulation to activate their flight-or-fight reaction and are considered more emotionally stable.

More recently, Jeffrey Gray suggested that these two broad traits are related to fundamental reward and avoidance systems in the brain. Extraverts might be motivated to seek reward, and thus exhibit assertive, reward-seeking behaviour, whereas people high in neuroticism might be motivated to avoid punishment, and thus may experience anxiety as a result of their heightened awareness of the threats in the world around them (Gray, 1981). This model has since been updated (Gray & McNaughton, 2000).

Based on these two dimensions, the Eysencks’ theory divides people into four quadrants. These quadrants are sometimes compared with the four temperaments described by the Greeks: melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic, and sanguine.

Later, the Eysencks added a third dimension: psychoticism versus superego control. In this dimension, people who are high on psychoticism tend to be independent thinkers, cold, nonconformists, impulsive, antisocial, and hostile, whereas people who are high on superego control tend to have high impulse control — they are more altruistic, empathetic, cooperative, and conventional (Eysenck et al., 1985).

The Big Five

While Cattell’s 16 factors may be too broad, the Eysencks’ two-factor system has been criticized for being too narrow. Another personality theory, called the Big Five, effectively hits a middle ground, with its five factors referred to as the Big Five personality factors. It is the most popular theory in personality psychology today and the most accurate approximation of the basic personality dimensions (Funder, 2001). The five factors are: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. A helpful way to remember the factors is by using the mnemonic CANOE.

The following YouTube link shows Gabriela Cintron’s student-made video, which cleverly describes common behavioural characteristics of the Big Five personality traits through song:

Watch this video: 5 Factors of Personality (OCEAN Song) (3 minutes)

“5 Factors of Personality (OCEAN Song)” video by Vy Nguyen is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

In the Big Five, each person has each factor, but they occur along a continuum.

- Openness to experience is characterised by imagination, feelings, actions, and ideas. People who score high on this factor tend to be curious and have a wide range of interests.

- Conscientiousness is characterised by competence, self-discipline, thoughtfulness, and achievement-striving (goal- directed behaviour). People who score high on this factor are hardworking and dependable. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between conscientiousness and academic success (Akomolafe, 2013; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008; Conrad & Patry, 2012; Noftle & Robins, 2007; Wagerman & Funder, 2007).

- Extroversion is characterised by sociability, assertiveness, excitement-seeking, and emotional expression. People who score high on this factor are usually described as outgoing and warm. Not surprisingly, people who score high on both extroversion and openness are more likely to participate in adventure and risky sports due to their curious and excitement-seeking nature (Tok, 2011).

- Agreeableness refers to the tendency to be pleasant, cooperative, trustworthy, and good-natured. People who score low on agreeableness tend to be described as rude and uncooperative, yet one recent study reported that men who scored low on this factor actually earned more money than men who were considered more agreeable. This negative correlation between agreeableness and income was not supported in women (Judge et al., 2012).

- Neuroticism refers to the tendency to experience negative emotions. People high on neuroticism tend to experience emotional instability and are characterised as angry, impulsive, and hostile. People reporting high levels of neuroticism often report feeling anxious and unhappy (Watson & Clark,1984). In contrast, people who score low in neuroticism tend to be calm and even-tempered.

The Big Five personality factors each represent a range between two extremes. In reality, most of us tend to lie somewhere midway along the continuum of each factor, rather than at polar ends. It’s important to note that the Big Five factors are relatively stable over our lifespan, with some tendency for the factors to increase or decrease slightly. Researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008). Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years (Terracciano et al., 2005). Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008; Terracciano et al., 2005). Additionally, the Big Five factors have been shown to exist across ethnicities, cultures, and ages, and may have substantial biological and genetic components (Jang et al., 1996, 2006; McCrae & Costa, 1997; Schmitt et al., 2007).

Below is a short scale to assess the five-factor model of personality (Donnellan et al., 2006). You can take this test to see where you stand in terms of your Big Five scores.

The Mini-IPIP Scale

Below are phrases describing people’s behaviours. Use the rating scale below to describe how accurately each statement describes you. Describe yourself as you generally are now, not as you wish to be in the future. Describe yourself as you honestly see yourself, in relation to other people you know of the same sex and roughly your same age. Read each statement carefully, and put a number from 1 to 5 next to it to describe how accurately the statement describes you.

Scale

1 = Very inaccurate

2 = Moderately inaccurate

3 = Neither inaccurate nor accurate

4 = Moderately accurate

5 = Very accurate

Questions

- Am the life of the party (E)

- Sympathize with others’ feelings (A)

- Get chores done right away (C)

- Have frequent mood swings (N)

- Have a vivid imagination (O)

- Don’t talk a lot (E)

- Am not interested in other people’s problems (A)

- Often forget to put things back in their proper place (C)

- Am relaxed most of the time (N)

- Am not interested in abstract ideas (O)

- Talk to a lot of different people at parties (E)

- Feel others’ emotions (A)

- Like order (C)

- Get upset easily (N)

- Have difficulty understanding abstract ideas (O)

- Keep in the background (E)

- Am not really interested in others (A)

- Make a mess of things (C)

- Seldom feel blue (N)

- Do not have a good imagination (O)

How to Analyze Results

To analyse the results, first reverse the score for items 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20 by subtracting the number you gave yourself from 6. For instance, your score of 4 will become a 2 (6 – 4 = 2). Replace your original score (4) with the new number (2). ().

Next, add up the scores for each of the five CANOE scales, as indicated by the letter following each item: C, A, N, O or E. Each letter score will be the sum of four items. Place the sum next to each scale below.

- Conscientiousness: Add items 3, 8, 13, 18

- Agreeableness: Add items 2, 7, 12, 17

- Neuroticism: Add items 4, 9,14, 19

- Openness: Add items 5, 10, 15, 20

- Extraversion: Add items 1, 6, 11, 16

Compare your scores to the norms below to see where you stand on each scale. If you are low on a trait, it means you are the opposite of the trait label. For example, low on extraversion is introversion, low on openness is conventional, and low on agreeableness is assertive.

19–20 Extremely High, 17–18 Very High, 14–16 High, 11–13 Neither high nor low, 8–10 Low, 6–7 Very low, 4–5 Extremely low

(Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, 2006)

Trait theorists agree that personality traits are important in understanding behaviour, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important. For example, Michael Ashton and Kibeom Lee (2005) argued that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Big Five model. Their HEXACO model adds honesty-humility as a sixth dimension of personality. People high in honesty-humility are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in this trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centred. You may go to the HEXACO website to learn more about the HEXACO model and download the scales in different languages.

Adaptive Traits

Like trait theorists, evolutionary psychologists look at personality traits that are universal. In this view, adaptive differences have evolved and then provide a survival and reproductive advantage. David Buss (1991) has identified five adaptive traits:

- Surgency indicates a person’s preference in a hierarchy. A surgent person tends to dominate and lead others.

- Agreeableness marks a person’s willingness to cooperate; however, it is not always maladaptive to be selfish and hostile toward others.

- Conscientiousness signals to others whom we can trust and whom we can depend on; however, being less conscientious and dependent on others is not maladaptive.

- Emotional stability indicates one’s ability to handle stress. Although hypersensitivity to stress may disrupt everyday functioning and thus is less favoured, vigilance and anxiety may be adaptive and necessary to avoid harm and threat.

- In ancestral times, openness (or intellect) might be expressed in one’s willingness to explore new territories for food and shelter and one’s creativity in solving problems.

Heritability of Traits and Temperament

Most contemporary psychologists believe temperament has a biological basis due to its appearance very early in our lives (Rothbart, 2011). Thomas and Chess (1977) found that babies could be categorised into one of three temperaments: easy, difficult, or slow to warm up. Mary Rothbart and colleagues proposed two temperaments in adulthood — reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart et al., 2000). Reactivity refers to how we respond to new or challenging environmental stimuli; self-regulation refers to our ability to control that response (Rothbart et al., 2011). For example, one person may immediately respond to new stimuli with a high level of anxiety, while another barely notices it.

In the field of behavioural genetics, the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart — a well-known study of the genetic basis for personality — conducted research with twins from 1979 to 1999. In studying 350 pairs of twins, including pairs of identical and fraternal twins reared together and apart, researchers found that identical twins, whether raised together or apart, have very similar personalities (Bouchard, 1994; Bouchard et al.,1990; Segal, 2012). These findings suggest the heritability of some personality traits. Heritability refers to the proportion of difference among people that is attributable to genetics. Some of the traits that the study reported as having more than a 0.50 heritability ratio include leadership, obedience to authority, a sense of well-being, alienation, resistance to stress, and fearfulness. The implication is that some aspects of our personalities are largely controlled by genetics; however, it’s important to point out that traits are not determined by a single gene, but by the complex relationship among the various genes, as well as a variety of random factors. Genetic factors work with environmental factors to create personality. Having a given pattern of genes does not necessarily mean that a particular trait will develop because some traits might occur only in some environments. For example, a person may have a genetic variant that is known to increase their risk for developing emphysema from smoking, but if that person never smokes, then emphysema most likely will not develop.

One question that is exceedingly important for the study of personality concerns the extent to which it is the result of nature or nurture. If nature is more important, then our personalities will form early in our lives and may be difficult to change later. If nurture is more important, then our experiences are likely to be particularly important, and our personalities may change in response to experiences over time. While identical twins Paula Bernstein and Elyse Schein turned out to be very similar even though they had been raised separately, those traits that they share are likely to be the result of genes, but environments, particularly those that are unique to individuals, are important in shaping personality as well. In the next section, we will see how personality can be influenced by environments.

Image Attributions

Figure PE.9. Figure 14.8 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure PE.10. Hans and Sybil Eysenck by Sirswindon is licensed under a CC BY 3.0 license.

Figure PE.11. Figure 11.13 as found in Psychology 2e by OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure PE.12. Algerian Desert by Gruban is licensed under a CC BY-SA 2.0 Generic license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).