Chapter 12. Emotion

What are Emotions?

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 10 minutes

What are the Basic and Secondary Emotions?

The most basic emotions in the scientific literature are anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. These basic emotions help us make rapid judgments about stimuli and to quickly guide appropriate behaviour (LeDoux, 2000). The basic emotions are determined in large part by one of the oldest parts of our brain, the limbic system, including the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the thalamus. (Note: We will explore the biology of emotions in greater depth later on in this chapter.) Basic emotions are experienced and displayed in much the same way across cultures (Ekman, 1992; Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Fridland, Ekman, & Oster, 1987), and people, on average, are quite accurate at judging the facial expressions of people from different cultures.

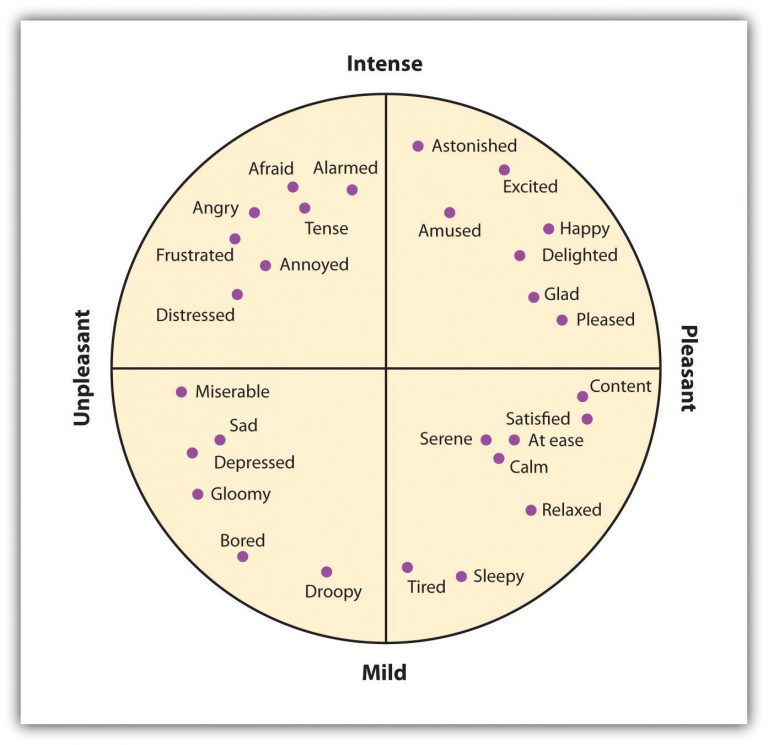

Not all of our emotions come from the old parts of our brain; we also interpret our experiences to create a more complex array of emotional experiences. For instance, the amygdala may sense fear when it senses that the body is falling, but that fear may be interpreted completely differently, perhaps even as excitement, when we are falling on a roller-coaster ride than when we are falling from the sky in an airplane that has lost power. The cognitive interpretations that accompany emotions — known as cognitive appraisal — allow us to experience a much larger and more complex set of secondary emotions (Figure EM.3). Although they are in large part cognitive, our experiences of the secondary emotions are determined in part by arousal, as seen on the vertical axis of Figure EM.3, and in part by whether they are pleasant or unpleasant feelings — termed valence — as seen on the horizontal axis of Figure EM.3.

The study of disgust, pioneered by researchers like Paul Rozin, reveals its complex nature and societal implications. Rozin’s experiments demonstrate how disgust can be triggered by simple association, regardless of any real threat of contamination. For instance, most people would refuse to eat chocolate fudge shaped like dog poop, even knowing it was delicious chocolate, illustrating Rozin’s Law of Similarity: “If it looks like an X, it’s an X” (Aarøe, Petersen, & Arceneaux, 2017).

Disney’s Pixar Studio brilliantly plays with our sense of disgust in “Ratatouille,” a movie about an unlikely talented chef, a rat named Remy, who befriends and mentors a novice human cook at a prestigious Parisian restaurant. Initially, this movie prompts us to recoil at the thought of a rat in the kitchen, “Eeew!” However, the movie then challenges us to confront our ingrained disgust towards rats. As we watch Remy cook, our initial revulsion turns into admiration for his skill and passion. The film demonstrates that our feelings of disgust can be unlearned or changed through new experiences and understanding, aligning with the notion that disgust, while a natural defense mechanism, is also deeply influenced by social and cultural factors (Bhikram, Abi-Jaoude, & Sandor, 2017).

Emotions play a vital role in our everyday experiences and decision-making processes. They help us react to events quickly and understand our deeper feelings about situations. For instance, when something good happens, we might feel joy and satisfaction, while negative events can bring about feelings like anger or sadness. Understanding how our brains process these emotions can give us insight into why we react the way we do. This section explores the difference between primary and secondary emotions and how our brain’s pathways contribute to these emotional experiences.

Primary emotions, such as fear, anger, happiness, and sadness, are our initial, instinctive responses to stimuli and are typically quick and automatic. These emotions are fundamental and are often shared across different cultures. Secondary emotions, on the other hand, are more complex and arise from our interpretations and evaluations of situations. They are influenced by our thoughts, experiences, and social contexts, leading to feelings like pride, guilt, jealousy, and embarrassment. Understanding the distinction between these two types of emotions can help us better manage our reactions and interactions with others.

For example, when you succeed in reaching an important goal, you might spend some time enjoying your secondary emotions, perhaps the experience of joy, satisfaction, and contentment. But when your close friend wins a prize that you thought you deserved, you might also experience a variety of secondary emotions like anger, sadness, resentment or shame. You might even think about the event for weeks or even months, experiencing these negative emotions each time you think about it (Martin & Tesser, 2006).

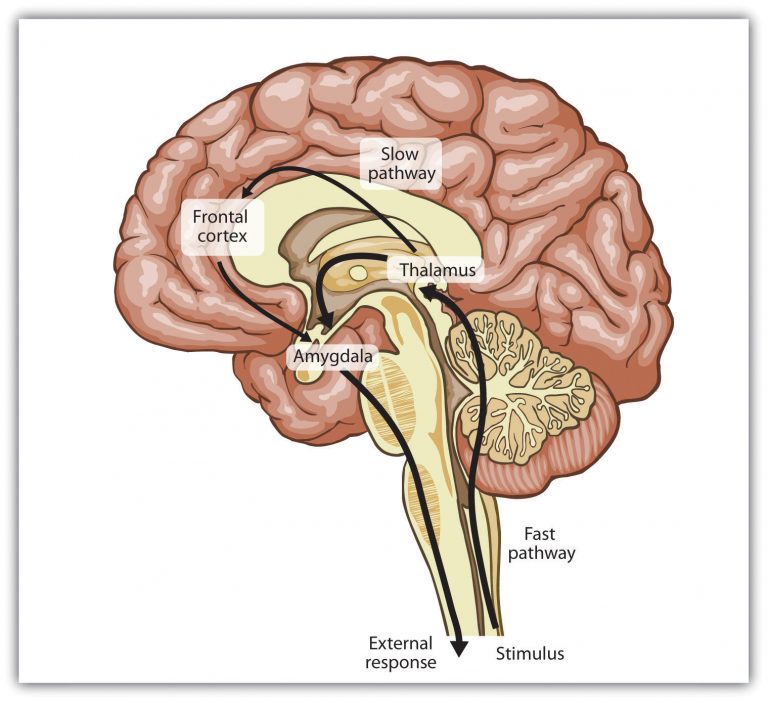

The difference between the primary and the secondary emotions has a parallel in the neuroanatomy of two brain pathways: a fast pathway and a slow pathway (Damasio, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002). The thalamus acts as the major gatekeeper in this process (Figure EM.4), meaning that it decides what sensory information gets passed on to the brain. Our response to the basic emotion of fear, for instance, is primarily determined by the fast pathway through the limbic system. When a car pulls out in front of us quickly on the highway, the thalamus activates and sends an immediate message to the amygdala. We quickly move our foot to the brake pedal.

Secondary emotions are determined more by the slow pathway through the frontal lobes in the cortex. When we are jealous of someone our partner has a crush on, or remember our win playing a video game, the process is more complex. Information moves from the thalamus to the frontal lobes for cognitive analysis and integration, and then from there to the amygdala. We experience the arousal of emotion, but it is accompanied by a more complex cognitive appraisal, producing more refined emotions and behavioural responses.

Both emotions and cognitions can help us make effective decisions. In some cases, we take action after rationally processing the costs and benefits of different choices, but in other cases, we rely on our emotions. Emotions become particularly important in guiding decisions when the alternatives between many complex and conflicting alternatives present us with a high degree of uncertainty and ambiguity, making a complete cognitive analysis difficult. In these cases, we often rely on our emotions to make decisions, and these decisions may in many cases be more accurate than those produced by cognitive processing (Damasio, 1994; Dijksterhuis, Bos, Nordgren, & van Baaren, 2006; Nordgren & Dijksterhuis, 2009; Wilson & Schooler, 1991).

Summary: Scientific Language of Emotions/ Basic and Secondary Emotions

This section delves into the intricate world of emotions, distinguishing between emotions, feelings, moods, and meta-moods, and introduces the concept of emodiversity. It defines emotions as complex reactions to significant life events, feelings as the personal experience of these emotions, moods as longer-lasting emotional states not directly linked to a specific cause, and meta-moods as our awareness and contemplation of our own emotional states. Emodiversity is highlighted as the variety and richness of emotions an individual can experience, which is crucial for psychological resilience and overall well-being.

Furthermore, the section outlines the basic and secondary emotions, providing insight into the broad spectrum of human emotional experiences. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for understanding how emotions play a critical role in our lives, influencing our behaviour, decision-making, and interpersonal relationships.

Now that we have explained the general overview of emotion-related terminology, in the next sections, we will go on to explore several scientific theories of emotion in detail.

Image Descriptions

Figure EM.3. Secondary Emotions image description: A graph that places emotions on two axes. The Y axis is from Mild to Intense and the X axis is from Unpleasant to Pleasant.

Intense and unpleasant: (Generally listed from most unpleasant and most mild to most pleasant and most intense)

- Distressed

- Frustrated

- Annoyed

- Angry

- Tense

- Afraid

- Alarmed

Intense and pleasant: (Generally listed from most unpleasant and most intense to most pleasant and most mild)

- Astonished

- Excited

- Amused

- Happy

- Delighted

- Glad

- Pleased

Mild and unpleasant: (Generally listed from most unpleasant and most intense to most pleasant and most mild)

- Miserable

- Depressed

- Sad

- Gloomy

- Bored

- Droopy

Mild and pleasant: (Generally listed from most unpleasant and most mild to most pleasant and most intense)

- Tired

- Sleepy

- Relaxed

- Serene

- Calm

- At ease

- Satisfied

- Content

Image Attributions

Figure EM.3. Figure 11.2 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

Figure EM.4. Figure 11.3 as found in Psychology – 1st Canadian Edition is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA License.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).