Chapter 6. States of Consciousness

What is Consciousness

Jessica Motherwell McFarlane

Approximate reading time: 37 minutes

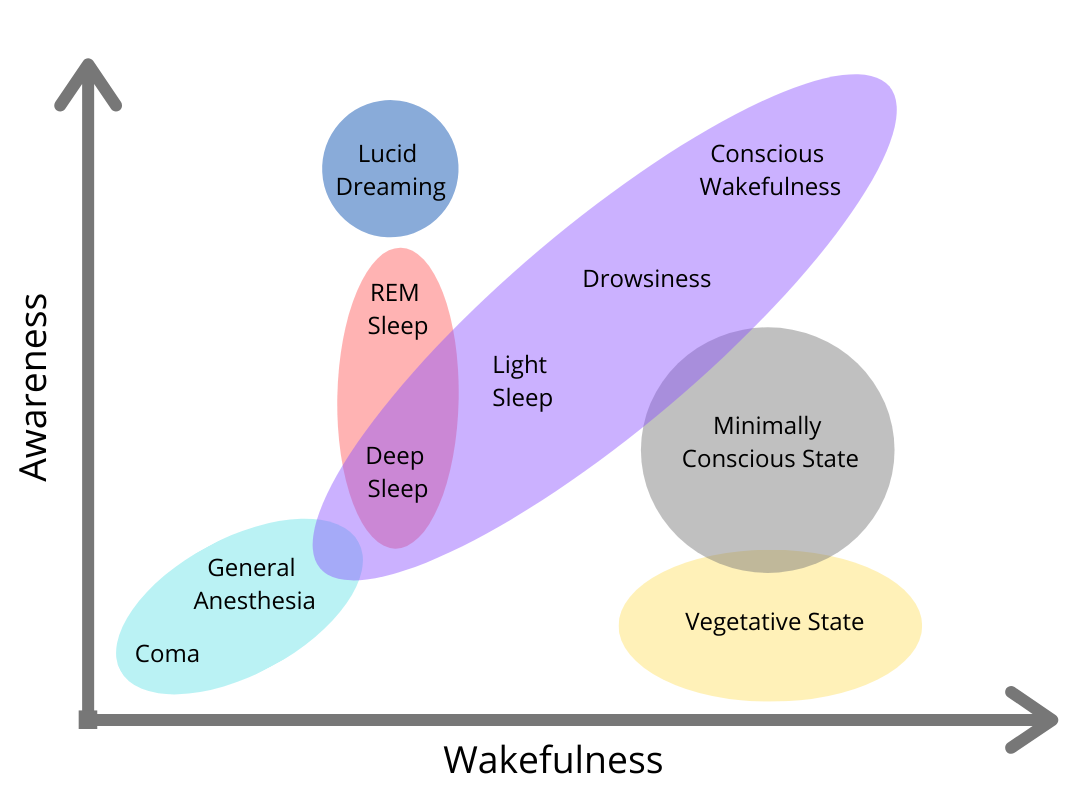

We experience different states of consciousness and different levels of awareness on a regular basis. We might even describe consciousness as a continuum that ranges from full awareness to deep sleep. Sleep is a state marked by relatively low levels of physical activity and reduced sensory awareness that is distinct from periods of rest that occur during wakefulness. Wakefulness is characterised by high levels of sensory awareness, thought, and behaviour.

Beyond being awake or asleep, people experience many other states of consciousness. These include daydreaming, intoxication, and unconsciousness due to anaesthesia. Often, we are not completely aware of our surroundings, even when we are fully awake.

For instance, have you ever found yourself lost in thought while walking to class or back to your room? You navigate the campus, avoid obstacles, and maybe even greet friends, all without actively thinking about these actions. You’re able to perform all these complex tasks while your mind is elsewhere. This is an example of how many of our processes, much like a lot of psychological behaviours, are deeply rooted in our biology.

Anaesthesia is a medical treatment that helps prevent or reduce pain during surgery or other medical procedures. It can make you partially or completely unconscious, so you don’t feel pain or discomfort.

Consciousness States Defined

- Awareness: The state or ability to perceive, feel, or be conscious of events, objects, or sensory patterns. In this context, it refers to the level of consciousness and cognitive function.

- Coma: A state of deep unconsciousness in which a person fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle, and does not initiate voluntary actions. (See footnote below on medically-induced coma)

- Conscious Wakefulness: A state of being awake and aware of one’s surroundings, thoughts, and feelings.

- Deep Sleep: A stage of sleep characterised by slow brain waves and a lack of eye movement and muscle activity. It is a period of heavy sleep from which it is difficult to wake up.

- Drowsiness: A state of feeling sleepy or being on the verge of sleep.

- General Anaesthesia: A medically induced coma with loss of protective reflexes, resulting from the administration of one or more general anaesthetic agents.

- Light Sleep: A stage of sleep where the person is in a lighter state of sleep and can be awakened easily.

- Lucid Dreaming: A type of dreaming where the dreamer is aware that they are dreaming and may have some control over their dreams.

- Minimally Conscious State: A condition of severely altered consciousness but with some signs of self-awareness or awareness of one’s environment.

- REM Sleep (Rapid Eye Movement Sleep): A unique phase of sleep characterised by random rapid movement of the eyes, low muscle tone throughout the body, and the propensity of the sleeper to dream vividly.

- Vegetative State: A condition where a person is awake but showing no signs of awareness.

- Wakefulness: The state or quality of being awake. In the context of the graph, it refers to the degree of alertness or the ability to respond to stimuli.

Watch this video: Consciousness: Crash Course Psychology (9.5 minutes)

“Consciousness: Crash Course Psychology #8” video by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Coma

A coma is a deep state of unconsciousness where an individual does not respond to external stimuli like light or sound (Young, 2009). It differs from sleep because the person cannot be woken. Comas are caused by an injury to the brain, which can be due to various reasons such as severe head injury, stroke, brain tumour, drug or alcohol intoxication, or an underlying illness like diabetes or an infection (Stevens, Cadena, & Pineda, 2015).

In a coma, the patient shows minimal to no voluntary activities and does not respond to pain, light, or sound in a normal way. They also might not have normal reflex responses and may not be able to breathe without assistance (Rappaport, Dougherty, & Kelting, 1992). Coma durations can vary widely, presenting a range from very brief periods to extended lengths of time. The shortest recorded comas, often resulting from mild traumatic brain injuries, can last less than 15 minutes (Gennarelli et al., 1982).

On the other end of the spectrum, the longest comas, typically associated with severe traumatic and hypoxic brain injuries, have been documented to last for over two years (Klimash and Zhanaidarov (2017). Recovery depends on the severity of the brain injury and the cause of the coma; some patients may regain full function, while others may sustain permanent brain damage or never regain consciousness (Dalmau & Graus, 2018).

Watch this video: Tricky Topics: Measuring Consciousness (11.5 minutes)

“Tricky Topics: Measuring Consciousness” video by FirstYearPsych Dalhousie is licensed under the Standard YouTube licence.

Attention and Vigilance

Attention and vigilance are key concepts in psychology that help us understand how we interact with the world. Attention is about how we focus on certain things around us. Attention shapes our experiences and who we are. It comes in different forms, like being able to focus on one thing for a long time or manage several things at once. Vigilance is about keeping this focus for longer periods, especially when it’s important to notice rare or unexpected events (Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008). Together, these two processes help us process information, whether it’s for a short moment or over a longer time.

Attention

“Attention is the beginning of devotion.” Mary Oliver (2016).

“Your life, who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love — is the sum of what you focus on.” Winifred Gallagher (2009).

“Millions of items of the outward order are present to my senses which never properly enter into my experience. Why? Because they have no interest for me. My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind. Without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.” William James (1890, pp. 403-404).

The above authors teach us that there is a conscious aspect of our attention. While our awareness is often controlled by us, sometimes outside events grab our attention. These authors remind us that our ability to process information is limited. We can only focus on a relatively small amount of information at any time.

Attention is a set of processes that guide psychological and neural processing to identify and select relevant events against competing distractions (Nobre, 2015). In simpler terms, attention is like a mental spotlight that our brain uses to focus on specific things while filtering out others. It helps us concentrate on what is important at a given moment, whether it’s a conversation, a task, or something we’re observing, by tuning out irrelevant or less important information and distractions around us.

There are different kinds of attention. Sustained attention is about staying focused on one task for a long time. Divided attention is about how well we can focus on many things at once. Spatial attention is about how we focus on one part of our environment and then shift our focus to other parts. All these types involve selective attention, where we focus on some information and ignore other information (Cherry, 1953; Moray, 1959).

Selective attention means choosing specific things in our environment to focus on, while ignoring others. To understand how attention works, think about being at a party. There are many people, colours, sounds, and smells. Many conversations are happening. How do we focus on just one? We might be listening to gossip while pretending not to. Once we’re in a conversation, we can’t focus on others at the same time. We might not notice how tight our shoes are or the smell of cookies baking in the oven nearby. But if someone mentions our name, we usually notice and might start listening to that conversation. This shows that we can focus on one thing even with many distractions. But we can’t focus on everything at once. This highlights how our brain picks and chooses what to focus on, using our attention to filter out less important details and concentrate on what matters most.

Using the context of a person winning a video game can be a great way to explain the different types of attention. Here’s a mnemonic that aligns with this theme:

Study Hint: “Stick-to-it, Divide, Scan, Select”

Photo by Alena Darmel is licensed under the Pexels license.

- Stick-to-it (Sustained Attention): Like a gamer staying focused on a long strategy game, sustained attention is about maintaining concentration on a single task for an extended period without getting distracted.

- Divide (Divided Attention): Imagine a player simultaneously handling multiple challenges in a fast-paced game. This is divided attention, where one manages to focus on several tasks at once.

- Scan (Spatial Attention): Like a player scanning a game map to keep track of enemies and objectives, spatial attention involves shifting focus across different areas within the environment.

- Select (Selective Attention): Similar to a gamer selecting the most crucial information on the screen during a chaotic battle, selective attention is about filtering out less important stimuli to focus on what’s most important in the current context.

The party situation is a classic example of selective attention. Early researchers tried to mimic this party phenomenon in labs to understand attention’s role in perception (Cherry, 1953; Moray, 1959). They used dichotic listening and shadowing tasks. Dichotic listening means listening to two different messages at the same time, one in each ear. In shadowing, a person repeats one of those messages as they hear it.

Example

Dichotic Listening. Imagine Nahanee, wearing the same special headphones, hears a favourite podcast in her left ear and an interesting story in her right ear. Instead of being asked to repeat the story in one ear, Nahanee is asked to listen to both simultaneously and then report what she heard from both the podcast and the story afterward.”

In this scenario, Nahanee would have to split her attention between both ears, trying to process both the podcast and the story at the same time. This tests her ability to perceive and recall information from both audio streams, which is characteristic of dichotic listening experiments.

Shadowing. Imagine Nahanee, wearing special headphones, hears a favourite podcast in her left ear and an interesting story in her right ear. Nahanee is asked to repeat the story that she hears in her right ear. Can Nahanee complete this without letting her favourite podcast (in her left ear) distract her?

People can get good at the above shadowing task. They can remember the message they focused on. But what about the message they ignored? Usually, they can only describe the voice’s pitch but not its content. In Nahanee’s situation that would mean she will have to re-listen to her podcasts because she will not have been able to pay close enough attention to understand the podcast.

These studies highlight the highly selective nature of our attention. Often, we may not notice significant changes in our environment, such as failing to realise when a speaker’s voice changes in the background. Classic research by Cherry (1953) and Moray (1959) demonstrated that people frequently overlook a change in the language of a message they are not focusing on, or even if the same word is repeated multiple times in an unattended message. This indicates that while we can concentrate on certain details, we might miss others.

In sum, attention allows us to gather the information we need to understand our world. Next we will explore how vigilance takes attention a step further by requiring us to maintain this focus over longer periods, often in situations where the stakes are high, and the cost of errors is significant.

Vigilance

Vigilance in psychology is defined as the capacity to maintain attention and alertness over extended periods, particularly when tasked with detecting infrequent or unpredictable events or changes in an environment (Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008). This concept is crucial in scenarios where the occurrence of these events is rare, but the consequences of missing them are significant. Contrary to the belief that prolonged vigilance deteriorates performance, it’s actually interruptions by pop-up tasks that can lead to mind wandering and missed monitoring opportunities (Casner & Schooler, 2015).

Example

Imagine training a support dog for blind people to maintain the dog’s focus on their person’s needs while walking in a busy park. The main task for the dog is to watch for and act on specific cues from the trainer. When a squirrel dashes past, however, the dog’s attention instantly shifts from the task to the squirrel. The tempting distraction of a squirrel temporarily breaks the dog’s concentration and hinders the dog’s training progress.

This example highlights how even a single unexpected distraction can be a threat to maintaining vigilance. Remember, in your studies, think of distractions as the’ squirrels’ that you need to manage to keep your focus sharp!

There are several important types of vigilance.

Types of vigilance

- Sustained Attention requires prolonged focus, differing from tasks that require short-term, intense concentration (Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008).

- Signal Detection involves identifying specific, often rare stimuli among a background of non-significant stimuli, requiring heightened perceptual sensitivity (Discussed in the Sensation and Perception chapter; See, 2014).

- Mental Endurance is the repetitive and monotonous nature of vigilance tasks that demands considerable mental stamina to remain attentive (Hancock & Warm, 1989).

- Error Sensitivity is the potential for significant consequences from errors, such as missed signals or false alarms, a critical aspect of vigilance tasks (Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008). This sensitivity to errors is a critical aspect of vigilance tasks, where the cost of errors can be significant. Error sensitivity refers to the potential impact or consequences of errors made during a task. It’s about how critical an error can be and the severity of its consequences.

What impacts vigilance?

- Vigilance decrement happens when, over time, the ability to maintain vigilance tends to decrease. It is characterised by reduced signal detection (Warm, Parasuraman, & Matthews, 2008; Claypoole et al., 2017).

- Psychophysiological factors: Cognitive and physiological factors like fatigue, boredom, or stress can impact vigilance, with individual differences affecting performance (Hancock & Warm, 1989).

- Environmental and task influences: Task design and environmental factors, including task complexity, can significantly affect vigilance (See, 2014).

Some of these types of vigilance is further explained in Supplement SC.1.

Summary

In summary, attention and vigilance are closely linked but different parts of how we think and process information. Attention is the first step — it helps us choose and think about the information we take in from everything around us. It prepares us for more complex tasks, like focusing, dividing our attention, and picking out important details. Vigilance builds on this by emphasising the need to keep this focus for a long time, especially when it’s crucial to notice rare things. These processes are important in many situations, from social gatherings to critical jobs like air traffic control. They shape our experiences and help us stay safe and effective in both everyday life and in more demanding tasks.

This section introduces the intricate nature of consciousness, focusing on its various states and how they impact our daily lives and understanding of the self. It outlines the fundamental aspects of consciousness, including the conditions that alter or affect it, such as comas, and delves into the cognitive processes of attention and vigilance. These topics are explored to shed light on how individuals process and respond to their environment, emphasising the importance of sustained attention in both routine tasks and critical ones, like air traffic control. The narrative aims to provide a comprehensive overview of consciousness, from its definition to the practical implications of its different states on human behaviour and mental processes.

Image Attributions

Figure SC.3. Figure SC.2 as found in Introduction to Psychology & Neuroscience (2nd Edition) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License.

Figure SC.4. Photo by Alena Darmel is licensed under the Pexels license.

To calculate this time, we used a reading speed of 150 words per minute and then added extra time to account for images and videos. This is just to give you a rough idea of the length of the chapter section. How long it will take you to engage with this chapter will vary greatly depending on all sorts of things (the complexity of the content, your ability to focus, etc).