Main Body

Chapter 7. Travel Services

Heather Knowles and Morgan Westcott

Learning Objectives

- Describe the key characteristics of the travel services sector

- Define key travel services terminology

- Differentiate between types of reservation systems and booking channels

- Discuss the impacts of online travel agents on consumers and the sector

- Identify key travel services and organizations in Canada and British Columbia

- Explain the importance of additional tourism services not covered under NAICS

- Describe key trends and issues in travel services worldwide

Overview

The travel services sector is made up of a complex web of relationships between a variety of suppliers, tourism products, destination marketing organizations, tour operators, and travel agents, among many others. Under the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), travel services comprises businesses and functions that assist with planning and reserving components of the visitor experience (Government of Canada, 2014).

Before we move on, let’s explore the term travel services a little more. As detailed in Chapter 1, Canada, the United States, and Mexico all use NAICS guidelines, which define the tourism industry as consisting of transportation, accommodation, food and beverage, recreation and entertainment, and travel services.

For many years, however, the tourism industry was classified into eight sectors: accommodations, adventure and recreation, attractions, events and conferences, food and beverage, tourism services, transportation, and travel trade (Yukon Department of Tourism and Culture, 2013). As you can see, most of these — from accommodations to food and beverage — remain virtually the same under NAICS and have been covered thus far in this textbook.

Tourism services support industry development and the delivery of guest experiences, and some of these are missing from the NAICS classification. To ensure you have a complete picture of the tourism industry in BC, this chapter will cover both the NAICS travel services activities and some additional tourism services.

First, we’ll review the components of travel services as identified under NAICS, exploring the function of each area and ways they interact:

- Travel agencies

- Online travel agencies (OTAs)

- Tour operators

- Destination marketing organizations (DMOs)

- Other organizations

Following these definitions and descriptions, we’ll take a look at some other support functions that fall under tourism services. These include sector organizations, tourism and hospitality human resources organizations, training providers, educational institutions, government branches and ministries, economic development and city planning offices, and consultants.

Finally, we’ll look at issues and trends in travel services, both at home, and abroad.

Components of Travel Services

While the application of travel services functions are structured somewhat differently around the world, there are a few core types of travel services in every destination. Essentially, travel services are those processes used by guests to book components of their trip. Let’s explore these services in more detail.

Travel Agencies

A travel agency is a business that operates as the intermediary between the travel industry (supplier) and the traveller (purchaser). Part of the role of the travel agency is to market prepackaged travel tours and holidays to potential travellers. The agency can further function as a broker between the traveller and hotels, car rentals, and tour companies (Goeldner & Ritchie, 2003). Travel agencies can be small and privately owned or part of a larger entity.

A travel agent is the direct point of contact for a traveller who is researching and intending to purchase packages and experiences through an agency. Travel agents can specialize in certain types of travel including specific destinations; outdoor adventures; and backpacking, rail, cruise, cycling, or culinary tours, to name a few. These specializations can help travellers when they require advice about their trips. Some travel agents operate at a fixed address and others offer services both online and at a bricks-and-mortar location. Travellers are then able to have face-to-face conversations with their agents and also reach them by phone or by email. Travel agents usually have a specialized diploma or certificate in travel agent/travel services (go2HR, 2014).

Today, travellers have the option of researching and booking everything they need online without the help of a travel agent. As technology and the internet are increasingly being used to market destinations, people can now choose to book tours with a particular agency or agent, or they can be fully independent travellers (FITs), creating their own itineraries.

Online Travel Agents (OTAs)

Increasing numbers of FITs are turning to online travel agents (OTAs), companies that aggregate accommodations and transportation options and allow users to choose one or many components of their trip based on price or other incentives. Examples of OTAs include Booking.com, Expedia.ca, Hotwire.com, and Kayak.com. OTAs are gaining popularity with the travelling public; in 2012, they reported online sales of almost $100 billion (Carey, Kang, & Zea, 2012) and almost triple that figure, upward of $278 billion, in 2013 (The Economist, 2014).

In early 2015 Expedia purchased Travelocity for $280 million, merging two of the world’s largest travel websites. Expedia became the owner of Hotels.com, Hotwire, Egencia, and Travelocity brands, facing its major competition from Priceline (Alba, 2015).

Although OTAs can provide lower-cost travel options to travellers and the freedom to plan and reserve when they choose, they have posed challenges for the tourism industry and travel services infrastructure. As evidenced by the merger of Expedia and Travelocity, the majority of popular OTA sites are owned by just a few companies, causing some concern over lack of competition between brands. Additionally, many OTAs charge accommodation providers and operators a commission to be listed in their inventory system. Commission-based services, as applied by Kayak, Expedia, Hotwire, Hotels.com, and others, can have an impact on smaller operators who cannot afford to pay commissions for multiple online inventories (Carey, Kang & Zea, 2012). Being excluded from listings can decrease the marketing reach of the product to potential travellers, which is a challenge when many service providers in the tourism industry are small or medium-sized businesses with budgets to match.

Finally, governments are stepping in as they see OTAs as a barrier to collecting full tax revenues on accommodations and transportations sold in their jurisdictions. OTAs frequently charge taxes on the retail price of the component; however, they purchase these products at a discount, remitting only the portion collected on the lesser amount to the government. In other words, the OTA pockets the difference between taxes collected and taxes remitted (Associated Press, 2014).

Some believe this practice shortchanges the destination that is ultimately responsible for delivering the tourism experience. These communities rely on tax revenue to pay for infrastructure related to the visitor experience. Recent lawsuits, including one by the state of Montana against a group of OTAs, have highlighted this challenge. To date, the courts have sided with OTAs, sending the message that these companies are not responsible for collecting tax on behalf of government (Associated Press, 2014).

While the industry and communities struggle to keep up with the changing dynamics of travel sales, travellers are adapting to this new world order. One of these adaptations is the ever-increasing use of mobile devices for travel booking. The Expedia Future of Travel Report found that 49% of travellers from the millennial generation (which includes those born between 1980 and 1999) use mobile devices to book travel (Expedia Inc., 2014), and these numbers are expected to continue to increase. Travel agencies are reacting by developing personalized features for digital travellers and mobile user platforms (ETC Digital, 2014). With the number of smartphones users expected to reach 1.75 billion in 2014 (CWT Travel Management Institute, 2014) these agencies must adapt as demand dictates.

A key feature of travel agencies’ mobile services (and to a growing extent transportation carriers) includes the ability to have up-to-date itinerary changes and information sent directly to their phone (Amadeus, 2014). By using mobile platforms that can develop customized, up-to-date travel itineraries for clients, agencies and operators are able to provide a personal touch, ideally increasing customer satisfaction rates.

Take a Closer Look: Expedia – The Future of Travel Report

Expedia is the largest online travel agency in the world. Formed in 1996, Expedia Inc. now oversees a variety of online travel booking companies. Together they provide travellers with the option to book flights, hotels, tours, and transportation through mobile or desktop online functions. For more on Expedia’s thoughts on the future of travel, read its report at Expedia’s report on the Future of Travel: http://expediablog.co.uk/The-Future-of-Travel/

Despite the growth and demand for OTAs, travel agencies are still in demand by leisure travellers (Hotel Marketing, 2013). The same is true for business travellers, especially in markets such as China and Latin America. Business clients in these emerging markets place a premium on “high-touch” services, such as paper tickets delivered by hand, and in-person reservations services (BTN Group, 2014).

Tour Operators

A tour operator packages all or most of the components of an offered trip and then sells them to the traveller. These packages can also be sold through retail outlets or travel agencies (CATO, 2014; Goeldner & Ritchie, 2003). Tour operators work closely with hotels, transportation providers, and attractions in order to purchase large volumes of each component and package these at a better rate than the traveller could if purchasing individually. Tour operators generally sell to the leisure market.

Inbound, Outbound, and Receptive Tour Operators

Tour operators may be inbound, outbound, or receptive:

- Inbound tour operators bring travellers into a country as a group or through individual tour packages (e.g., a package from China to visit Canada).

- Outbound tour operators work within a country to take travellers to other countries (e.g., a package from Canada to the United Kingdom).

- Receptive tour operators (RTOs) are not travel agents, and they do not operate the tours. They represent the various products of tourism suppliers to tour operators in other markets in a business-to-business (B2B) relationship. Receptive tour operators are key to selling packages to overseas markets (Destination BC, 2014) and creating awareness around possible product.

Destination Marketing Organizations

Destination marketing organizations (DMOs) include national tourism boards, state/provincial tourism offices, and community convention and visitor bureaus around the world. DMOs promote “the long-term development and marketing of a destination, focusing on convention sales, tourism marketing and service” (DMAI, 2014).

Spotlight On: Destination Marketing Association International

Destination Marketing Association International (DMAI) is the global trade association for official DMOs. It is made up of over 600 official DMOs in 15 countries around the world. DMAI provides its members with information, resources, research, networking opportunities, professional development, and certification programs. For more information, visit the Destination Marketing Association International website: www.destinationmarketing.org

With the proliferation of other planning and booking channels, including OTAs, today’s DMOs are shifting away from travel services functions and placing a higher priority on destination management components.

Working Together

One way tour operators, DMOs, and travel agents work together is by participating in familiarization tours (FAMs for short). These are usually hosted by the local DMO and include visits to different tour operators within a region. FAM attendees can be media, travel agents, RTO representatives, and tour operator representatives. FAMs are frequently low to no cost for the guests as the purpose is to orient them to the tour product or experience so they can promote or sell it to potential guests.

Other Organizations

The majority of examples in this chapter so far have pertained to leisure travellers. There are, however, specialty organizations that deal specifically with business trips.

Spotlight On: Global Business Travel Association Canada

Internationally, the Global Business Travel Association (GBTA) represents over 7,000 business travel agents and corporate travel and meeting managers who collectively manage over $340 billion in business travel and meetings each year (GBTA, 2014). The Canadian chapter, headquartered in Ontario, holds annual events and shares resources on its website. For more information, visit the Global Business Travel Association: www.gbta.org/Canada/

Business Travel Planning and Reservations

Unlike leisure trips, which are generally planned and booked by end consumers using their choice of tools, business travel often involves a travel management company, or its online tools. Travel managers negotiate with suppliers and ensure that all the trip components are cost effective and comply with the policies of the organization.

Many business travel planners rely on global distribution systems (GDS) to price and plan components. GDS combine information from a group of suppliers, such as airlines. In the past, this has created a chain of information from the supplier to GDS to the travel management company. Today, however, there is a push from airlines (through the International Air Transport Association’s Resolution 787) to dissolve the GDS model and forge direct relationships with buyers (BTN Group, 2014).

Destination Management Companies

According to the Association of Destination Management Executives (ADME), a destination management company (DMC) specializes in designing and implementing corporate programs, including “events, activities, tours, transportation and program logistics” (ADME, 2014). The packages produced by DMCs are extraordinary experiences rather than general business trips. These are typically used as employee incentives, corporate retreats, product launches, and loyalty programs. DMCs are the one point of contact for the client corporation, arranging for airfare, airport transfers, ground transportation, meals, special activities, and special touches such as branded signage, gifts, and decor (ADME, 2014). The end user is simply given (or awarded) the package and then liaises with the DMC to ensure particular arrangements meet his or her needs and schedule.

As you can see, travel services range from online to personal, and from leisure to business applications. Now that you have a general sense of the components of travel services, let’s look at some examples in Canada and BC.

Travel Services in Canada and BC

Travel Agencies

In British Columbia and elsewhere in Canada, many agencies are members of the Association of Canadian Travel Agencies (ACTA). ACTA is an industry-led, membership-based organization that aims to ensure customers have professional and meaningful counselling. Membership is optional, but it does offer the benefit of ensuring customers receive the required services and that the travel agencies have a membership board for reference and industry resources (ACTA, 2014).

Spotlight On: Travel CUTS Travel Agency

Travel CUTS is 100% Canadian owned and operated. As a student, you may have seen its locations on or around campus. With a primary audience of postsecondary students, professors, and alumni, Travel CUTS specializes in backpack-style travel to a variety of destinations. It is a full-service travel agency that can help find flights for travel, book tours with a variety of companies including GAdventures or Intrepid Travel, assist in booking hostels or hotels, and even help with the SWAP overseas VISA program. For more information, visit Travel CUTS: www.travelcuts.com

Although travel agencies may be located in a specific community, the agencies and their representatives may operate internationally, within Canada, within BC, or across regions. In Vancouver alone there are over 500 travel agencies available to the searching traveller (Travel Agents in BC, 2014). Examples of some of the more recognized larger travel agencies and agents operating in BC include the British Columbia Automobile Association (BCAA), Marlin Travel, and Flight Centre.

Tour Operators

Many different types of tour operators work across BC and Canada. Tour operators can specialize in any sector or a combination of sectors. A company may focus on ski experiences, as is the case with Destination Snow, or perhaps wine tours in the Okanagan, which is the specialty of Distinctly Kelowna Tours. These operators specialize in one area but there are others that work with many different service providers.

Spotlight On: Canadian Association of Tour Operators

The Canadian Association of Tour Operators (CATO) is a membership-based organization that serves as the voice of the tour operator segment and engages in professional development and networking in the sector. For more information, visit the Canadian Association of Tour Operators: www.cato.ca

Tour operators can vary in size, niche market, and operation capacity (time of year). An example of a niche BC tour operator is Prince of Whales Whale Watching in Victoria. Prince of Whales offers specialty whale-watching tours year-round in a variety of boat sizes, working with the local DMO and other local booking agents to sell tours as part of packages or as a stand-alone service to travellers. It also works to sell its product directly to the potential traveller through its website, reservation number, and in-person sales agents (Prince of Whales, 2014).

Examples of large RTOs representing Canada internationally include Jonview or CanTours. Operators of all kinds frequently work closely with a number of destination marketing organizations, as evidenced during Canada’s West Marketplace, which is a trade marketplace hosted by Destination BC and Travel Alberta. Each year the location of the marketplace alternates between Alberta and BC (past locations have included Kelowna and Canmore). This event provides an opportunity for Alberta and BC sellers (tour operators, local accommodation, activities, and DMOs) to sell their products to international RTOs who in turn work with international tour operators and travel agents to repackage the travel products. In a span of 10-minute sessions, sellers market and promote their products in hopes of having an RTO pick up the package for future years.

On a national scale, Rendez-vous Canada is a tourism marketplace presented by the Canadian Tourism Commission that brings together more than 1,500 tourism professionals from around the world for a series of 12- minute sessions where they can learn more about Canadian tours and related services (Canadian Tourism Commission, 2015).

Let’s now look a little closer at the role of BC destination marketing organizations (DMOs) in providing travel services.

Destination Marketing Organizations

At the national level, the Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC) is responsible for strategic marketing of the country. It works with industry and government while providing resources for small and medium-sized businesses in the form of toolkits. In BC, there a variety of travel service providers available to help with the planning process including Destination BC/HelloBC, regional destination marketing organizations (RDMOs), and local DMOs.

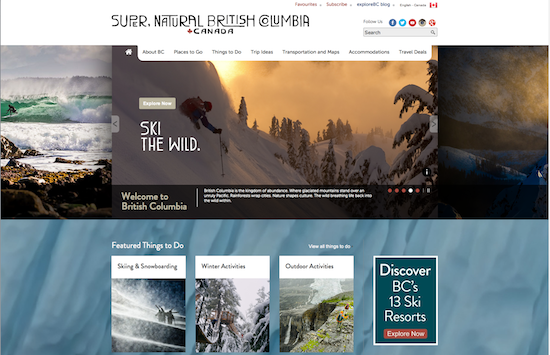

Destination BC/HelloBC

HelloBC is the official travel service platform of Destination BC, British Columbia’s provincial DMO. HelloBC.com offers access to festival activities, accommodation, transportation options, and trip ideas. This website is complemented by a social media presence through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (HelloBC, 2014a). Although the online resources are highly detailed, visitors also have the option of ordering a paper copy of the BC Travel Guide.

To assist with trip planning, HelloBC features a booking agent system, offering discounts and special deals created in partnership with operators. Although the site can process these value-added components, it does not handle accommodation bookings, instead directing the interested party to the reservation system of a chosen provider.

In addition to operating HelloBC, Destination BC also oversees a network of 136 Visitor Centres that can be identified by the blue and yellow logo. These are a source of itinerary information for the FIT and a purchase point for travellers wishing to book trip components (HelloBC, 2014b).

Regional Destination Marketing Organizations

BC is divided into five regional destination marketing organizations, or RDMOs: Vancouver Island, Thompson Okanagan, Northern British Columbia, Cariboo Chilcotin Coast and the Kootenay Rockies (HelloBC, 2014c). Along with Destination BC, these RDMOs work to market their particular region.

Housed within the HelloBC online platform, each RDMO has an online presence and travel guide specific to the region as well as a regional social media presence. These guides are important as they allow regional operators to participate in the guide and consumer website in order to encourage visitation to the area and build their tourism operations.

Take a Closer Look: BC’s Regional DMOs

For more information on each RMDO, visit the following consumer and industry sites:

Vancouver Island

Consumer: Vancouver Island: www.hellobc.com/vancouver-island.aspx

Industry: Vancouver Island: www.tourismvi.ca

Thompson Okanagan

Consumer: Okanagan: www.hellobc.com/thompson-okanagan.aspx

Industry: Okanagan: www.totabc.org/corporateSite/

Northern British Columbia

Consumer: Northern BC: www.hellobc.com/northern-british-columbia.aspx

Industry: Northern BC: www.travelnbc.com/

Cariboo Chilcotin Coast

Consumer: Cariboo Chilcotin Coast: www.hellobc.com/cariboo-chilcotin-coast.aspx

Industry: Cariboo Chilcotin Coast: www.landwithoutlimits.com/

Kootenay Rockies

Consumer: Kootenay Rockies: www.hellobc.com/kootenay-rockies.aspx

Industry: Kootenay Rockies: www.krtourism.ca/

Community Destination Marketing Organizations

Community destination marketing organizations (CDMOs) are responsible for marketing a specific destination or area, such as Whistler or Kimberley. Travel services typically offered include hotel search engines, specific destination packages and offers, discounts, events and festival listings, and other information of interest to potential visitors. In the absence of a CDMO, sometimes these services are provided by the local chamber of commerce or economic development office.

Spotlight On: Tourism Tofino

Tourism Tofino is the local DMO for the Tofino area, located on the west side of Vancouver Island. Tofino is a destination region that attracts travellers to Pacific Rim National Park, surfing opportunities, storm watching, and the Pacific Ocean. As part of its marketing tactics, Tourism Tofino offers visitors key planning tools on the landing site. To encourage shoulder season visitation, storm-watching deals are highlighted, which also allows visitors to inquire directly with the accommodation provider and/or tour operator. For more information, visit Tourism Tofino: www.tourismtofino.com

Complementing BC’s Visitor Centre network mentioned earlier, local visitor centres are managed by individual communities. Visitor centres may be housed in gateway buildings at strategic locations, in historic or cultural buildings, or at an office located in town. They are designed to provide general information to travellers and may include other services such as booking hotels, free Wi-Fi, and help from a visitor information counsellor (SGSEP, 2012).

Other Systems and Organizations

A number of customized and targeted reservation systems are used by BC DMOs and other organizations. One example is the BC campground reservation online booking systems. BC Parks, Parks Canada, and private campground operators all use different proprietary reservation systems. Both BC Parks and Parks Canada reservation systems open on a specific date in the spring for bookings later in the year. These systems let visitors review what a site looks like through photos or video and pick which site they would like to book in the campground. Many campgrounds also offer a first-come-first-served system, as well as overflow sites, to accommodate visitors who may not have reserved a site.

In the business market, there are several companies in BC and Canada that facilitate planning and booking. Concur is an example of a travel management company widely used in British Columbia and Canada by organizations including CIBC, Kellogg’s, and Pentax. It provides services including trip planning software for use by employees, expense and invoicing software for use by managers, and a mobile application that ensures clients can take the technology on the go. Its services have contributed to client savings, such as reducing the travel expenses for one client by almost one-fifth in their first year of use in Ontario (Concur, 2014).

BC is home to several DMCs including Cantrav, Pacific Destination Services, and Rare Indigo (Tourism Vancouver, 2014). All offer event services as well as turnkey operations (where all logistics are handled by the DMC and invoiced to the corporation).

So far we’ve looked at travel services as defined by NAICS. Next let’s have a closer look at additional services generally considered to be part of the tourism economy.

Tourism Services

Many organizations can have a hand in tourism development. These include:

- Sector-specific associations

- Tourism and hospitality human resources organizations

- Training providers

- Educational institutions

- Government branches and ministries in land use, planning, development, environmental, transportation, and other related fields

- Economic development and city planning offices

- Consultants

The rest of this section describes Canadian and BC-based examples of these.

Sector-Specific Associations

Numerous not-for-profit and arm’s-length organizations drive the growth of specific segments of our industry. Examples of these associations can be found throughout this textbook in the Spotlight On features, and include groups like:

- BC Hotel Association

- Sea Kayak Guides Alliance of BC

- Restaurants Canada

These can serve as regulatory bodies, advocacy agencies, certification providers, and information sources.

Tourism and Hospitality Human Resource Support

The Canadian Tourism Human Resource Council (CTHRC) is a national sector council responsible for best practice research, training, and other professional development support on behalf of the 174,000 tourism businesses and the 1.75 million people employed in tourism-related occupations across the country. In BC, an organization called go2HR serves to educate employers on attracting, training, and retaining employees, as well as hosts a tourism job board to match prospective employees with job options in tourism around the province.

Training Providers

Throughout this textbook, you’ll see examples of not-for-profit industry associations that provide training and certification for industry professionals. For example, the Association of Canadian Travel Agents offers a full-time and distance program to train for the occupation of certified travel counsellor. Closer to home, an organization called WorldHost, a division of Destination BC, offers world-class customer service training.

You’ll learn more about training providers and tourism human resources development in Chapter 9: Customer Service.

Educational Institutions

British Columbia is also home to a number of high-quality public and private colleges and universities that offer tourism-related educational options. Training options at these colleges and universities include certificates, diplomas, degrees and masters-level programs in adventure tourism, outdoor recreation, hospitality management, and tourism management. Whether students are learning how to manage a restaurant at Camosun College, gaining mountain adventure skills at College of the Rockies, or exploring the world of outdoor recreation and tourism management at the University of Northern BC, tomorrow’s workforce is being prepared by skilled instructors with solid industry experience.

Spotlight On: LinkBC

LinkBC is a membership-based organization that receives funding from Destination BC to support students and instructors at postsecondary institutions in connecting with the tourism industry. It hosts an annual Student Case Competition, a networking event called Student-Industry Rendezvous, and provides students with information about education options at its study tourism in BC website. For more information, visit the LinkBC website: http://linkbc.ca or Study Tourism in BC: www.studytourisminbc.ca

Government Departments

At the time this chapter was written, there were at least eight distinct provincial government ministries that had influence on tourism and hospitality development in British Columbia. These are:

- Community, Sport and Cultural Development

- Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training

- Advanced Education

- Transportation and Infrastructure

- Environment

- Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations

- International Trade

- Small Business and Economic Development

Ministry names and responsibilities may change over time, but the functions performed by provincial ministries are critical to tourism operators and communities, as are the functions of similar departments at the federal level.

At the community level, tourism functions are often performed by planning officers, economic development officers, and chambers of commerce.

Consultants

A final, hidden layer to the travel services sector is that of independent consultants and consulting firms. These people and companies offer services to the industry in a business-to-business format, and they vary from individuals to small-scale firms to international companies. In BC, tourism-based consulting firms include:

- IntraVISTAS: specializing in aviation and transportation logistics advising

- Chemistry Consulting: specializing in human relations and labour market development

- Tartan: a public-relations and reputation management firm

For many people trained in specific industry fields, consulting offers the opportunity to give back to the industry while maintaining workload flexibility.

Trends and Issues

Now that we have an understanding of the travel and tourism services providers in BC, let’s review some of the current trends and issues in the sector.

Budgets

In the travel services sector, providers such as OTAs and business travel managers must constantly be aware of price sensitivity. Many tourism services organizations are not-for-profit entities that rely on membership dues, donations, grants, and government funding to survive. As the economic climate becomes strained and budgets are tightened, all groups are increasingly forced to demonstrate return on investment to stakeholders. As some of the benefits of travel services are difficult to define, groups must innovate or face extinction.

The challenge of budget constraints came to life in late 2014 when Destination BC announced it was shutting down its Visitor Centres at Vancouver International Airport and reviewing five other gateway locations including Peace Arch and Golden. While the airport locations welcomed over 180,000 visitors per year, analysis performed by Destination BC showed guests were asking non-tourism questions, and the centres’ value was questioned. Closing the centres at the airport, it was determined, would save $500,000 per year — but some in the industry were left wondering why they weren’t consulted prior to the announcement (Smyth, 2014).

Technology

As discussed earlier, online travel agencies have revolutionized the sector in a short span of time. Online travel bookings and marketing accounts for roughly one-third of all global e-commerce, and according to many these continue to rattle the sector.

Take a Closer Look: The Trouble with Travel Distribution

This report, by McKinsey & Company, addresses the widespread impact of technological innovations on the travel services sector. To view the report online, visit The Trouble with Travel Distribution: www.mckinsey.com/insights/travel_transportation/the_trouble_with_travel_distribution

That said, OTAs and other technology providers can benefit operators and the travel services sector as a whole. Keeping in mind that travel services pertain to the planning and reserving of trip components, recent beneficial technologic improvements include the following (Orfutt, 2013):

- Real-time and automated inventory management, ensuring operators and travellers alike are working with accurate information when planning and booking

- A pollution and weather detection chip that would help tour operators, transportation providers, and visitors anticipate, and plan for changes in conditions

- Personalized information presented to visitors to help them narrow their choices in the trip planning process, ensuring users are not overwhelmed with information, and making the most of limited screen size on mobile devices and tablets

- Social technologies and on-the-go information sharing, allowing users to plan at the last minute as they travel

- Virtual assistant holograms and tablets carrying information that can replace humans during the travel experience (for instance, at airport arrivals and visitor centres)

These innovations will likely increase as more advances are made. They also have significant implications for the marketing of travel products and experiences, which is explored more in Chapter 8.

Conclusion

In a time when financial resources are limited and competition for tourist dollars is strong, the travel services sector is being forced to innovate at a startling rate. With the emergence of OTAs and the rapid pace of change, it’s likely the travel services landscape will be radically different by the time you read this.

Just 20 years ago, the travel agent was paramount for booking both leisure and business travel, while today’s traveller can book a trip using a phone in a matter of minutes. This is one sector with challenging and exciting times ahead.

To this point we have learned about the five sectors of tourism: transportation, accommodation, food and beverage, recreation and entertainment, and travel services. With this foundation in place, let’s delve deeper into the industry by learning more about how these sectors are promoted to customers in Chapter 8 on services marketing.

Key Terms

- Association of Canadian Travel Agencies (ACTA): a trade organization established in 1977 to ensure high standards of customer service, engage in advocacy for the trade, conduct research, and facilitate travel agent training

- Canada’s West Marketplace: a partnership between Destination BC and Travel Alberta, showcasing BC travel products in a business-to-business sales environment

- Canadian Association of Tour Operators (CATO): a membership-based organization that serves as the voice of the tour operator segment and engages in professional development and networking in the sector

- Community destination marketing organization (CDMO): a DMO that represents a city or town

- Destination management company (DMC): a company that creates and executes corporate travel and event packages designed for employee rewards or special retreats

- Destination marketing organizations (DMOs): also known as destination management organizations; includes national tourism boards, state/provincial tourism offices, and community convention and visitor bureaus

- Familiarization tours (FAMs): tours provided to overseas travel agents, travel agencies, RTOs, and others to provide information about a certain product at no or minimal cost to participants — the short form is pronounced like the start of the word family (not as each individual letter)

- Fully independent traveller (FIT): a traveller who makes his or her own arrangements for accommodations, transportation, and tour components; is independent of a group

- HelloBC: online travel services platform of Destination BC providing information to the visitor and potential visitor for trip planning purposes

- Inbound tour operator: an operator who packages products together to bring visitors from external markets to a destination

- Online travel agent (OTA): a service that allows the traveller to research, plan, and purchase travel without the assistance of a person, using the internet on sites such as Expedia.ca or Hotels.com

- Outbound tour operator: an operator who packages and sells travel products to people within a destination who want to travel abroad

- Receptive tour operator (RTO): someone who represents the products of tourism suppliers to tour operators in other markets in a business-to-business (B2B) relationship

- Regional destination marketing organization (RDMO): in BC, one of the five DMOs that represent a specific tourism region

- Tour operator: an operator who packages suppliers together (hotel + activity) or specializes in one type of activity or product

- Tourism services: other services that work to support the development of tourism and the delivery of guest experiences

- Travel agency: a business that provides a physical location for travel planning requirements

- Travel agent: an individual who helps the potential traveller with trip planning and booking services, often specializing in specific types of travel

- Travel services: under NAICS, businesses and functions that assist with the planning and reserving components of the visitor experience

- Visitor centre: a building within a community usually placed at the gateway to an area, providing information regarding the region, travel planning tools, and other services including washrooms and Wi-Fi

Exercises

- Explain, either in words or with a diagram, the relationship between an RTO, tour operator, and travel agent.

- What type of services does HelloBC provide to the traveller? List regional services from your area that are currently offered.

- Who operates the provincial network of Visitor Centres? Where are these centres located?

- List the RDMOs operating within BC. How do each of these work to provide information to the traveller?

- List two positives and two negatives of OTAs within the travel services industry.

- With an increase growth in mobile technology, how are travel services adapting to suit the needs and/or demands of the traveller?

- Choose an association that is representative of the sector you might like to work in (e.g., accommodations, food and beverage, travel services). Explore the association’s website and note three key issues it has identified and how it is responding to them.

- Choose a local tourism or hospitality business and find out which associations it belongs to. List the associations and their membership benefits to answer the question, Why belong to this group?

Case Study: Online Travel Agents Sue Skiplagger.com

Hidden city tickets work when the cost to travel from point A to point B to point C is less expensive than a trip from point A to point B. Passengers book the entire flight but get off at the stopover. This practice is generally forbidden by airlines because of safety concerns and challenges to logistics as it renders passenger counts inaccurate, causing potential delays and fuel miscalculations. If discovered, it can result in a passenger having his or her ticket voided.

The lawsuit against Skiplagged founder Aktarer Zaman stated that the site “intentionally and maliciously … [promoted] prohibited forms of travel” (Harris and Sasso, 2014, ¶ 4). Orbitz (an OTA) and United Airlines claimed that Zaman’s website unfairly competed with their business, while making it appear these companies were partners and endorsing the activity by linking to their websites.

Based on this case summary, answer the following questions:

- What are the dangers and inconveniences of having passengers deplane partway through a voyage? In addition to those listed here, come up with two more.

- Could this lawsuit and the ensuing publicity result in unintended negative consequences for United and Orbitz? What might these be?

- On the other hand, could the suit have unintended positive results for Skiplagged.com? Try to name at least three.

- Should Zaman be held responsible for facilitating this type of travel already in practice? Or should passengers bear the responsibility? Why or why not?

- Imagine your flight is delayed because a passenger count is inaccurate and fuel must be recalculated. What action would you take, if any?

- Look up the case to see what updates are available (United Airlines Inc. v. Zaman, 14-cv-9214, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Illinois (Chicago). Was the outcome what you predicted? Why or why not?

References

ACTA. (2014). About us. Retrieved from www.acta.ca/about-us

ADME. (2014). What is a DMC? Retrieved from www.adme.org/dmc/what-is-a-dmc.asp

Alba, Davey. (2015, January 23). Expedia buys Travelocity, merging two of the web’s biggest travel sites. WIRED. Retrieved from www.wired.com/2015/01/expedia-buys-travelocity-merging-two-webs-biggest-travel-sites/

Amadeus. (2014). Trending with NextGen travelers [PDF]. Retrieved from https://extranets.us.amadeus.com/whitepaper/nextgen/next_gen_travel_trends.pdf

Associated Press. (2014, March 17). Helena judge rejects state’s lawsuit against online travel companies. The Missoulian. Retrieved from http://missoulian.com/business/local/helena-judge-rejects-state-s-lawsuit-against-online-travel-companies/article_61b115d2-adfe-11e3-9b8d-0019bb2963f4.html

BTN Group. (2014). Global travel trends 2014. Business Travel News. [PDF] Retrieved from www.businesstravelnews.com/uploadedFiles/White_Papers/BTN_110113_Radius_1206_FINAL.pdf

Canadian Tourism Commission. (2015). Rendez-vous Canada 2015 – Welcome. Retrieved from http://rendezvouscanada.travel/

Carey, R., Kang, K., & Zea, M. (2012). The trouble with travel distribution. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com/insights/travel_transportation/the_trouble_with_travel_distribution

CATO. (2014). About the travel industry. Retrieved from www.cato.ca/industry.php

Concur. (2014). Concur case studies – Concur Canada. Retrieved from www.concur.ca/casestudy

CWT Travel Management Institute. (2014). Who’s equipped for mobile services. www.cwtinsights.com/demand/whos-equipped-for-mobile-services.shtml

DMAI. (2014). The value of DMOs. Retrieved from www.destinationmarketing.org/value-dmos

Economist, The. (2014, June 21). Sun, sea and surfing. Retrieved from www.economist.com/news/business/21604598-market-booking-travel-online-rapidly-consolidating-sun-sea-and-surfing

ETC Digital. (2014). Mobile smartphones – North America. Retrieved from http://etc-digital.org/digital-trends/mobile-devices/mobile-smartphones/regional-overview/north-america/

Expedia, Inc. (2014). The future of travel report. [PDF] Retrieved from http://expediablog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Future-of-Travel-Report1.pdf

GBTA. (2014). About GBTA Canada. Retrieved from www.gbta.org/Canada/about/Pages/Default.aspx

Goeldner, C. & Ritchie, B. (2003). Tourism: principles, practices, philosophies, 9th edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Government of Canada. (2014). NAICS 2007 – 5615 travel arrangement and reservation services. Retrieved from http://stds.statcan.gc.ca/naics-scian/2007/cs-rc-eng.asp?criteria=5615

go2HR. (2014). Training and education. Retrieved from www.go2hr.ca/training/training-directory?keys=travel+agent&location=§or=All®ion=All

Harris, A. & Sasso, M. (2014). United, Orbitz sue travel site over ‘hidden city’ tickets. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-11-18/united-orbitz-sue-travel-site-over-hidden-city-ticketing-1-

HelloBC. (2014a). About us. Retrieved from www.hellobc.com/british-columbia.aspx

HelloBC. (2014b). Visitor information network. Retrieved from www.hellobc.com/british-columbia/about-bc/visitor-centres.aspx

HelloBC. (2014c). Regions. Retrieved from www.hellobc.com/british-columbia.aspx

Hotel Marketing. (2013). Travel agency demand. Retrieved from http://www.hotelmarketing.com/index.php/content/article/travel_agencies_versus_the_internet_global_booking_trends/

Offutt, B. (2013). PhoCusWright’s travel innovations & technology trends: 2013 and beyond. [PDF] Retrieved from www.wtmlondon.com/files/pcwi_traveltechtrends2013_worldtravel.pdf

Prince of Whales. (2014). About us. Retrieved from http://princeofwhales.com

SGSEP. (2012). Trends in visitor information centres. [PDF] Urbecon, 1. Retrieved from www.sgsep.com.au/assets/Urbecon-Vol-1-2012-web.pdf

Smyth, M. (2014, November 20). Why is the BC government shutting down popular tourist info without consulting industry? The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from www.theprovince.com/life/Smyth+government+shutting+down+popular+tourist+info+centres+without+consulting+industry/10396500/story.html#__federated=1

Tourism Vancouver. (2014). Destination management companies. Retrieved from www.tourismvancouver.com/meetings/service-your-meeting/suppliers/destination-management-companies/

Travel Agents in BC. (2014). Travel agents. Retrieved from www.yellowpages.ca/search/si/1/Travel+Agencies/Vancouver+BC

Yukon Department of Tourism and Culture. (2013). Tourism sectors. Retrieved from www.tc.gov.yk.ca/isu_sectors.html

Attributions

Figure 7.1 HelloBC Homepage by LinkBC is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 7.2 Travels Agent, Huddersfield by Dave Collier is used under a CC-BY-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 7.3 my AT&T PC 6300 circa 1996 by Blake Patterson is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 7.4 Up on the glacier by Paul Gorbould is used under a CC BY NC ND 2.0 license.

Figure 7.5 Whales off Victoria, BC by Brian Estabrooks is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 7.6 Visitor Information by Heather Harvey is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 7.7 Floe Lake, Kootenay National Park 037 by Adam Kahtava is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 7.8 Tourism Vancouver’s Rick Antonson addresses the audience at Rendezvous by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 7.9 5 Top Rated Tablet PCs by Siddartha Thota is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.