Chapter 11. First Nations from Indian Act to Idle No More

11.1 Introduction

The experiences of Indigenous people since 1867 have appeared intermittently in the chapters of this history. As what Laurier called “Canada’s century” took shape, Canada became more urban and soon more modern; however, most Indigenous people did not travel this path. Overwhelmingly rural (insofar as the majority lived outside of city limits), confined to reserves in many cases, excluded from the modern industrial and technological economy by real and implicit barriers, mostly denied the fundamental rights of citizenship (including the vote), institutionalized and subjected to assimilationist policies while exposed to the worst expressions of racism, Indigenous people in Canada may be excused if they do not see themselves in the broad outlines of this country’s historic narrative.

Writing Indigenous history presents many challenges. Most of the documentation that has been easily available has come from sources whose job was to mainly manage or change or control First Nations. For structural and systemic reasons, Indigenous accounts have been fewer and further between. The effect of this limited Indigenous perspective has been the positioning of Indigenous people as a community on which history has acted, rather than as actors.

Opportunities to redress this stark imbalance have opened in the last 30 years. Indigenous historians, traditional oral accounts, and a succession of inquiries, royal commissions, court cases, and public hearings have given us the privilege of access to Indigenous voices from across the country. The effect has been to reposition Indigenous Canadians in the Canadian story, and to see that story, simultaneously, as a First Nations tale in which Canada is a mostly external but consistently imposing participant. So, the challenge is to put First Nations, Métis, and Inuit at the centre of the story and Canada at the edge.

This chapter begins with a consideration of the First Nations population over 150 years. No group in what became the provinces and territories of Canada has experienced such dramatic and confounding demographics. Subsequent sections explore aspects of the colonial relationship, attempting throughout to give priority to what Indigenous peoples thought they were pursuing. This approach involves a survey of the treaty process, efforts to assimilate Indigenous people into the economically and politically dominant non-Indigenous society, and growing expressions of frustration on the part of First Nations.

In the previous chapter, we explored aspects of modernity. The confidence that industrial urban society was the emergent pinnacle of civilization and the preferred model of human relations drove Canadians to disregard and attack alternative (alter-Native?) visions. As the modern gave way to the postmodern and as colonialism was confronted by post-colonialism, awareness grew among Indigenous peoples of the pathways that could restore and nurture back to health traditional relations and beliefs while also sharpening modernist beliefs about human rights into a weapon against the colonialists.

Indigenous histories in the northern half of North America are complex. They include tales of resilience and strength, but are sometimes so heavily laced with tragedy as to be unbearable. Due to the complex of jurisdictions and the enormous differences between, for example, the Nuu-chah-nulth, Niitsitapi, and Nippising, one cannot speak of one single history, although commonalities emerge. At the very least, one can say that Indigenous histories are the most effective way to understand Canada as a whole insofar as they hold up a mirror to both the dominant society and the very idea of Canada in a way that no other histories can.

Learning Objectives

- Assess the transformations of Indigenous peoples resource bases since 1867.

- Survey the main demographic changes in Indigenous societies in the 20th century.

- Describe the main contours of Indigenous-settler relations since 1867.

- Identify the main features of the Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples, and the issues they have created.

- Account for attempts to change Indigenous economies through schools and farming.

- Outline Indigenous peoples’ response to Canadian colonialism since WWII, and assess its effects.

- Describe and explain the changed political relationship between Indigenous people and the Canadian state since the 1990s.

Media Attributions

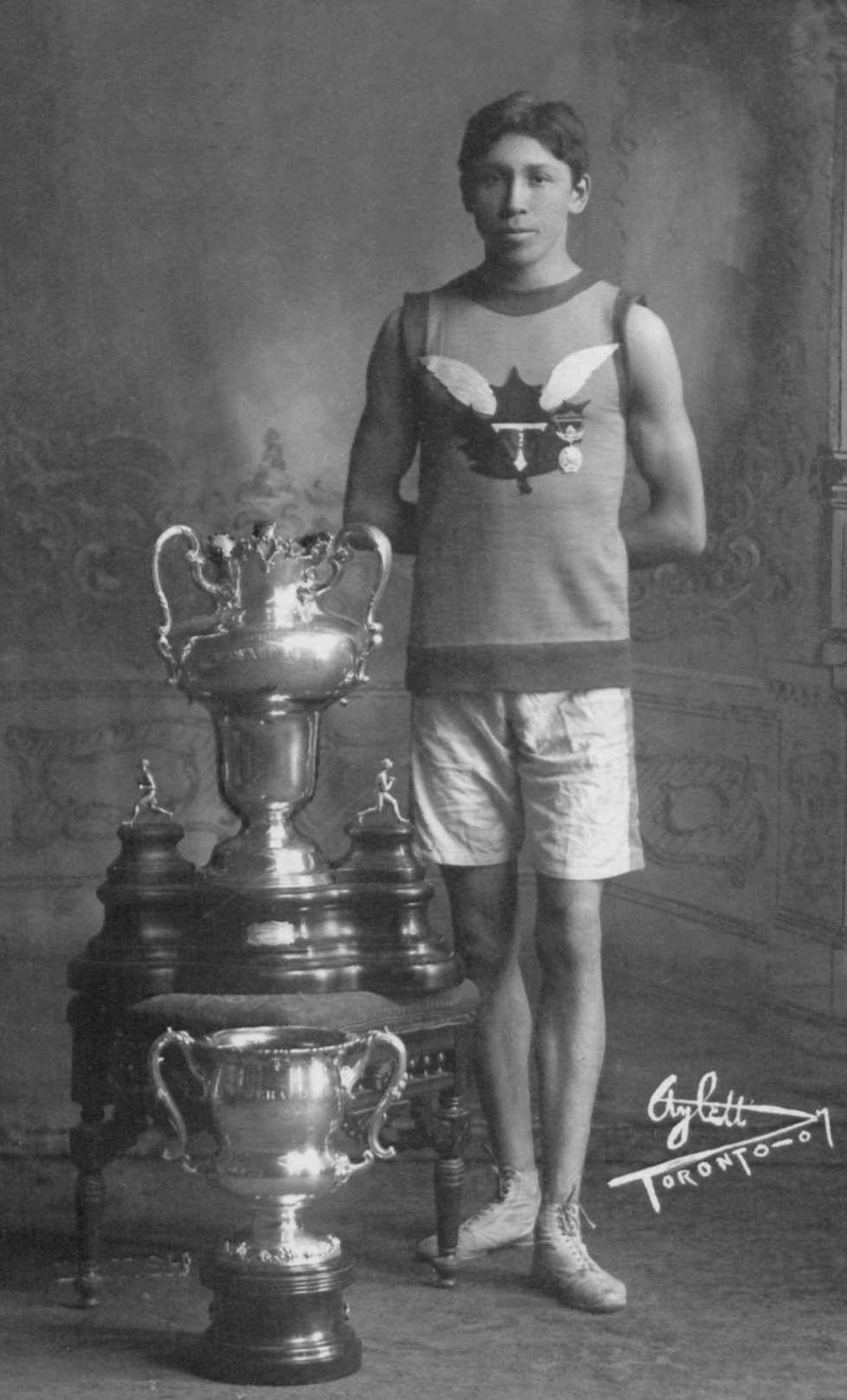

- Tom Longboat, the Canadian runner, 1907 © Charles Aylett is licensed under a Public Domain license

The range of experiences and perspectives that look beyond the paradigm of colonial society and colonialism; associated with the late 20th century.