Chapter 4. Politics and Conflict in Victorian and Edwardian Canada

4.4 The Sunny Ways of Sir Wilfrid Laurier

The years between Confederation and the Great War were dominated by two national politicians: Macdonald and Laurier. Between the two of them, they headed governments for 34 out of 47 years. Macdonald was prime minister for a longer amount of time, but Laurier won more consecutive elections. Both were devoted in very different ways to nation-building. Laurier’s contribution to Canadian political history is every bit as profound as Macdonald’s, as is his reinterpretation of the national culture.

Laurier in Quebec

As described previously, the Liberal Party distinguished itself from the Conservatives on the issue of the tariff. The 1850s Reciprocity Treaty was regarded by many as the key to prosperity. It gave Canadian farmers access to growing American urban markets and made the less expensive American manufactured products available in Canada; although the Liberal Party was strong in the cities, its anti-tariff position ensured that it would be more popular in the country’s farming districts. This explains some of the Party’s strength in Quebec, where rural cultural values were especially strong and important.

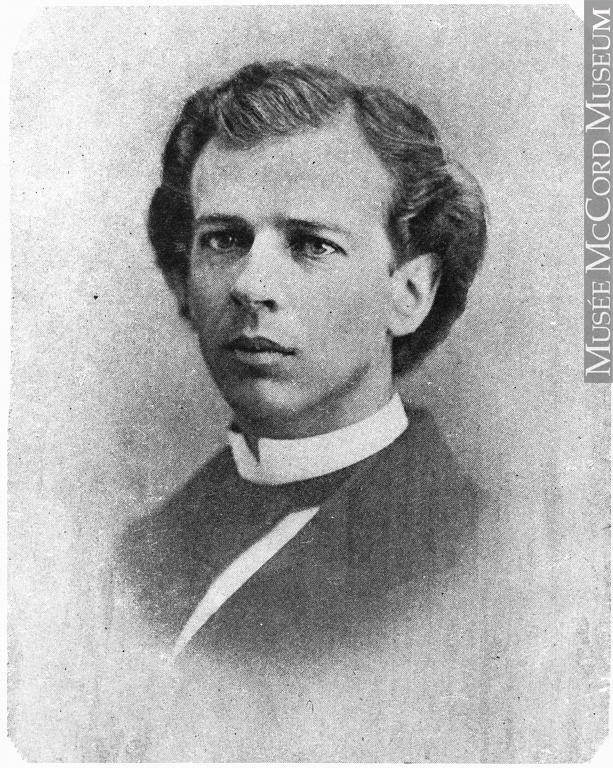

Laurier’s own background was not in farming. His father was a teacher and mayor in a small town north of Montreal. The young Laurier spent much of his childhood and youth studying in New Glasgow, where he was immersed in the culture and language of recent British immigrants to Quebec. He then trained in law at McGill, an uncommon accomplishment for a francophone at the time. His professional years were marked by struggle and intermittent poor health. Politically, he was a Rouge, and in 1866-67 he was entirely opposed to the concept of Confederation which, he wrote, constituted “the second stage on the road to ‘anglification’ mapped out by Lord Durham.”[1] He entered provincial politics first in 1871 at the age of 30, and quickly switched to federal affairs (and, at about the same time, had an extra-marital affair as well). A young French-Canadian lawyer with excellent ability in English, Laurier was too good to pass up when it came time for Mackenzie to form a cabinet in 1874: Laurier was appointed the Minister of Inland Revenue (which is roughly comparable to the current Canadian Revenue Agency).

Laurier’s relationship with the Catholic Church exemplifies some of the challenges of politics in late Victorian Quebec. Laurier was anticlerical, an advocate for the separation of church and state. This did not make him popular with the clergy, even though he saw himself as a champion for Catholics in Canada. He was, however, a powerful orator and, in 1877, was able to convince Bishop George Conroy (1832-1878) and an audience of 2,000 that the Liberal Party posed no threat to the rights of the Church — providing the Church did not use intimidation to chase votes toward the Conservative Party.

Despite a promising start, Laurier almost lost his way in the mid-1880s. He was influential in Quebec Liberal circles, but was not viewed so much as a leader anymore. Then Riel happened. Genuinely offended by the death sentence handed down to the Métis leader, Laurier also recognized an opportunity to forge links between Canadien nationalists of all stripes in Quebec. Riel was the wedge that could be driven between the Conservative Party on the one hand, and the Québecois electorate and the Catholic clergy on the other. Rising in the House of Commons, Laurier pointed a finger at Macdonald, accusing him of stirring up events in the West and persecuting a branch of the francophone and Catholic family. In one of his famous statements, while speaking before 50,000 people at the Champ-de-Mars rally days after Riel’s execution, Laurier suggested that had he been in Saskatchewan at the time, he would have taken up arms against the Ottawa government.

The Great Conciliator

An opponent of Confederation as a young man, Laurier appears to have returned to that position in his mid-40s. However, his kind of nationalism was one that accepted the federal system as an environment in which Quebec could, with the right guardians, thrive. This was a precisely dualist vision of the country: A vision in which both French and English coexist respectfully, and compromise is sought at all costs. When the Liberal Party failed once more at the polls in 1887, its leader Edward Blake (1833-1912) handpicked Laurier as his successor. (There were no leadership conventions at this time, just the discretion of the party leader.) It was a potentially disastrous choice, but possibly the shrewdest move in Blake’s otherwise unimpressive run.

Laurier failed to win government for the Liberals in 1891. Macdonald used the Liberals’ promise of “Universal Reciprocity” to whip up fear of an American takeover of Canada. In Quebec the Tories were able to mobilize an ultramontane fear of Laurier’s Rouge background to drive voters away from the Liberals. (The old saying in Quebec, alleged to have been coined by priests offering advice at election time, was “le ciel est bleu, l’enfer est rouge.” You can’t get much clearer direction than that!) It was a bitter reward for Laurier’s support of Macdonald during a dispute over a piece of Quebec legislation, The Jesuit Estates Act, 1888. In that instance both leaders called for tolerance of Papal intervention in a Quebec dispute over property claimed by several religious orders, a move that outraged Orange anti-Catholic feeling in Ontario. On the cultural and economic front, then, Laurier was measured and found wanting.

Five years later, the situation would be much changed. Macdonald was gone, the Conservative Party was careening from one endangered leader to the next, and — most importantly — the Liberals had come to terms with the tariff. The economy in the mid-1890s was desperately poor and the American response involved erecting a tariff wall of their own. Protectionism was the order of the day. What Laurier could promise, in good conscience, was no free trade for now but later, when the time became right. In embracing Macdonald’s National Policy, however gingerly, Laurier became electable. Once he abandoned the tariff (and he would do so in 1911), he would again become exposed.

One irony of Laurier’s rise to power is the role played by the Provincial Rights Movement (see Section 2.11). Oliver Mowat (1820-1903), the Premier of Ontario and the most effective and unrelenting advocate of decentralized confederation, was joined by Nova Scotian Premier William Fielding in an endorsement of Laurier. The ongoing acrimony between the provinces and Ottawa over federal powers had the effect of boosting the cause of the Liberals provincially: Both Mowat and Fielding were Liberals and thus motivated to see a change in Ottawa. What this meant, of course, is that Laurier wanted federal power but not so much of it that he would alienate his own base of support. He promised to build consensus rather than punish his foes: This was the crux of his commitment to “sunny ways.” History tends to view Laurier as a master of compromise, the Great Conciliator, and this (honouring provincial rights and holding federal power) was possibly his neatest trick. In 1896 he became prime minister.

Culture Wars

The first Laurier government faced several issues immediately. The foremost of these was the Manitoba Schools Act, 1870. Separate, publicly-funded schools for Catholics was an issue in all provinces. Prior to Confederation there was a consensus across British North America that religion and education could not only co-exist in the schools, but they were both essential parts of the moral and intellectual development of children. Where a church and community established a school, public funding generally followed. Confederation gave to the provinces exclusive authority over education so that a majority of MPs in Ottawa could not impose their denominational biases on the nation’s schools. Read simply, it was intended to stop Orangemen (from English Canada) attacking Catholic schools in Quebec. Although, the expectation was that Catholic and French language education elsewhere would be preserved and nurtured as well. The BNA Act, 1867, also guaranteed the continued funding of existing denominational schools in each of the provinces.

It was this second protection that was first to erode. As early as 1871 New Brunswick legislators were keen to move from denominational to secular education with a single, uniform curriculum, and with provincial government (rather than church) oversight. Welcomed by the Protestant denominations, this move was resisted strenuously by the Catholic (mostly Acadian) communities. The official Catholic position was that education was a matter for the clergy, and the state could not and should not interfere. Fredericton’s response was consistent with the anticlericalism that marked Victorian liberalism and modernism: The separation of church and state in civic life was necessary for the well-being of a successful democratic society. The Common Schools Act, 1871 became a flashpoint as Protestant legislators argued that there had been no pre-1867 formal arrangement with the denominational schools — so the Catholics had no rights to lose. The Catholic church, including Quebec’s Bishop Ignace Bourget (who would later be a nemesis of Laurier), encouraged their adherents to withhold school taxes and persuaded at least two Catholic members of the New Brunswick government to resign. Clergymen were arrested and property was seized in lieu of taxes. This increasingly rancorous disagreement culminated in tragedy in the Acadian community of Caraquet in 1875; a confrontation between a volunteer Protestant constabulary and Catholic opponents of the Common Schools Act came to blows, gunfire was exchanged, and both sides claimed one dead.

The New Brunswick case began under Macdonald’s watch and ended under Mackenzie’s. Neither federal administration was inclined to interfere, and each successive administration feared a replay in a different province. New Brunswickers found a route to compromise, but they’d paid a terrible price to get there. This was not a pattern anyone wished to reproduce, although the conflicting pressures — a modernist need for secular and consistent education versus a conservative clerical desire to control curriculum on faith and language — were not dissipating.

In the early 1890s this issue was coming to a head in Manitoba, and it became the most prominent matter during the 1896 federal election. One of the promises made in negotiations with the Red River Métis (in 1870) covered the provision of publicly-funded separate schools in which the Catholic faith and French language could be part of the curriculum. Declining numbers of Métis in Manitoba (and an increase of anti-Métis feeling after the 1885 Northwest Rebellion) constructed an argument for dispensing with separate schools. Premier Thomas Greenway (1838-1908), a notable advocate of provincial rights as early as 1883 and a Liberal by necessity as much as by inclination, saw in educational reform a chance to forge a common, pragmatic front among Liberals and Conservatives in Manitoba. His government put an end to the bilingual production of legislation and government records (a move that was overturned by the courts nearly a century later), effectively ended French as an official language in the province, and removed public funding from confessional schools. Parents who wished to send their children to a Catholic school could still do so, but they would have to pay the full costs directly and, in addition to that, they were expected to pay school taxes to support the secular, provincially-run system. There was widespread hope among federal politicians that this thorny issue might be resolved by the courts, but the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council responded that it was up to Ottawa. The Conservatives in Ottawa threatened to disallow the legislation but failed to do so before losing the 1896 election — in part, rather bizarrely, because Laurier blocked the passage of their disallowance bill. The Manitoba Schools Question now fell to Laurier to resolve.

The new Prime Minister’s response was one that would characterize his strategy of seeking compromise, one that he would follow for a generation. Laurier — through his delegate, Oliver Mowat — convinced Greenway to provide some very small degree of funding and support for French-language instruction and Catholic schools, although the official language issue stayed off the table. The compromise was based on numbers: 10 francophone pupils in rural areas or 25 in urban areas could trigger after-class instruction. The deal had the enormous political benefit of getting the issue off the federal agenda, which was a great relief to Laurier. Historians have pointed to the outcome as the inevitable result of a changing demographic and, in that context, Laurier is seen to have secured some reasonable if small concessions. Others have argued that this was a critical moment in Canadian history when Laurier sacrificed the principle of minority rights — and the federal government’s constitutional obligation to protect them — in order to entrench Anglo-Protestantism as the norm across the West. The consensus is that this example of compromise brought peace and that it was staged expertly, but that the concessions made by Manitoba were pitifully small and ungenerous.

The issue of education thereafter moved entirely to the provincial level. When Laurier’s ally, Premier Félix Marchand (1832-1900), attempted in 1890 to reform the education system in Quebec with an eye to taking it away from the clergy and into the hands of the state, he was defeated by an alliance of Anglican and Catholic elements in the province’s Legislative Council.[2] Laurier did not intervene.

Key Points

- Wilfrid Laurier was intermittently an opponent of Confederation.

- The execution of Riel was a turning point in Quebec politics and in Laurier’s career.

- The Liberal Party’s victory in 1896 was helped by Laurier’s willingness to mute the party’s commitment to free trade.

- Laurier was first tested as prime minister on the issue of separate schools. His compromising approach hints at what would become his modus operandi in successive crises.

Media Attributions

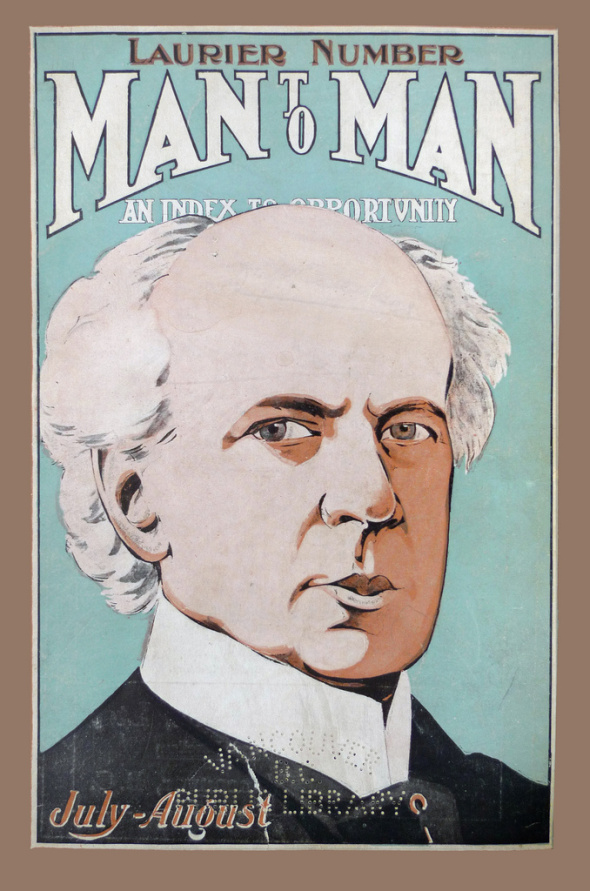

- Wilfrid Laurier on Man-to-Man Magazine © Man-to-Man Magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Wilfrid Laurier, 1874 © McCord Museum (MP-0000.1093.8) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Réal Bélanger, “LAURIER, Sir WILFRID”, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed 25 August 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laurier_wilfrid_14E.html. ↵

- Nova Scotia and Quebec retained their Legislative Councils into the 20th century. The Council in Halifax was dissolved in 1928, but the Quebec Council endured until 1968. The Legislative Councils acted as appointed provincial-level senates. Ontario never wrote one into its provincial constitution, BC never implemented plans to have one, and Manitoba, PEI, and New Brunswick were quick to dispose of theirs. The term used to describe a legislature with two tiers (in the Canadian case, typically called an Assembly and a Council) is “bicameral.” ↵

Also Parti rouge. Political party and tradition in Quebec; established in the 1840s, it became increasing more pro-secular, anticlerical, and opposed to hereditary privilege; opposed to Confederation, embraced provincial rights; after 1867, merged with the Clear Grits to form the Liberal Party.

Someone who believes that the separation of church and state in civic life is essential for the well-being of a successful democratic society.

Refers to the Orange Order, its members, and its values; a Protestant fraternal association with roots in Ireland; marked by a strong antipathy for Catholics and Catholicism, as well as a fierce loyalty to the Crown. Supported Protestant immigrants and made use of violence and political networks to achieve its ends.

Someone who believes that the separation of church and state in civic life is essential for the well-being of a successful democratic society.

In politics, the focus on existing conditions rather than ideological considerations or objectives. Also called realpolitik.

Religious schools run by Catholic or Protestant denominations.

In 1890 the provincial government turned its back on commitments in the Manitoba Act (1870) to provide a dual — French and English — system of education, a move that was stimulated by declining French and Catholic populations. The Privy Council determined (twice) that the federal government had the power to reverse this decision. In opposition, Wilfrid Laurier blocked Ottawa’s attempt at disallowance; in government he negotiated a compromise with Manitoba.