Chapter 11. First Nations from Indian Act to Idle No More

11.2 Environment and Colonialism

One of the more subtle features of colonialism is the way in which it creates environments that favour newcomers over natives. NASA defines terraforming — a staple of many science-fiction movies — as “the process of transforming a hostile environment into one suitable for human life.”[1] But what kind of “human life”? If it’s European human life, extensive grazing lands will be required for their dairy animals and meat herds, and even larger territories will be required for grain production and a variety of edible and non-edible crops that include tobacco and cotton, among others.

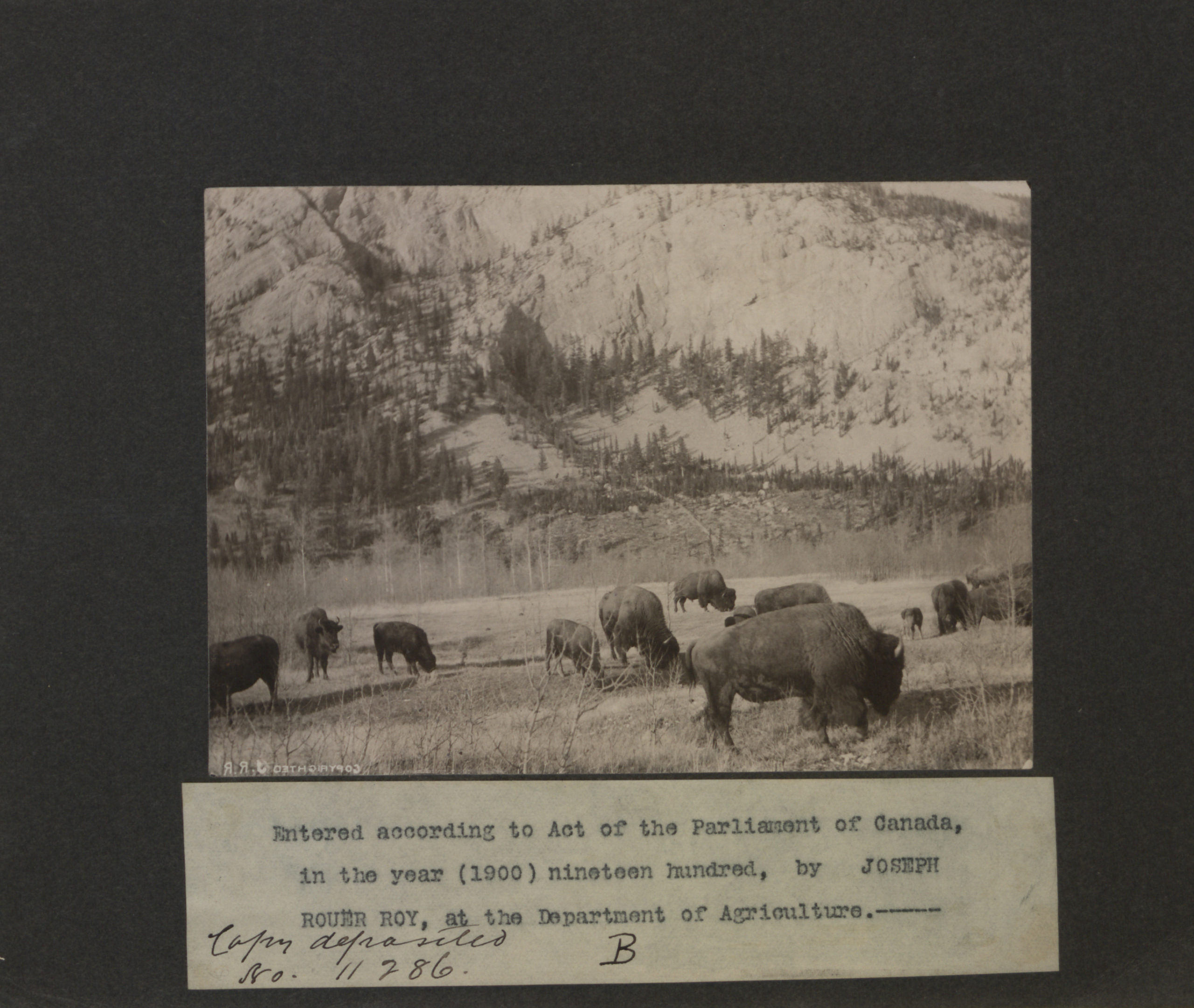

European societies effectively terraformed North America to make it more amenable to their familiar and preferred food sources. By doing so, the kinds of animals and plants on which innumerable generations of Indigenous peoples survived were reduced, removed, or eliminated. Bison herds, salal berries, camas roots, and many other resources were chased off, burned away, or ploughed under to make way for beef cattle, strawberries, and potatoes. This occurred in small plots across New France and British North America before 1867, and in the post-Confederation years, the wholesale transformation of the Prairie West under the plough is one of the most rapid and enormous examples of environmental colonialism in history. Accomplishing this required a reorganization of the land itself (into lots), the addition of modern-era infrastructure (roads, rails, airports), and the development of energy sources to keep this new economic order moving. From the mid-century to the present, hydroelectricity projects have had the greatest impact on indigenous populations. The Columbia and Peace River projects in British Columbia, Churchill Falls in Labrador, and the James Bay dams in northern Quebec have flooded more than a million hectares of land. There have been cases (BC’s Columbia Valley system, for example) where Euro-Canadians have been displaced, but these are the exceptions that prove the rule. Mostly “native land” has been terraformed so as to be unusable for anything other than the production of electricity.

Sometimes these changes have been less immediate but no less disastrous for Indigenous economies and communities. The commercial salmon fishery in Georgia Strait (aka: the Salish Sea) in the early part of the 20th century plundered the sockeye and spring runs so aggressively that fewer and fewer spawning fish made it into the Interior along the Fraser and Thompson River systems. Communities that relied on these resources, and which had fewer fallback alternatives, suffered from an industrialized fishery hundreds of miles away. However, the situation could be worse: it is thought that the Sacramento River in California was the largest salmon spawning ground on the west coast of North America in the 19th century, but today, the native fish are as good as extinct.

The loss of resources like salmon or bison is often used as a reason to relocate native communities. Having terraformed Canada to suit the needs of the Euro-Canadian food and economic cultures, Canadian administrators were tasked with finding spaces where alienated native people could be huddled together with alternative resources or services delivered from “the south.” Thus, relocations and their consequent economic marginalization became common themes in Indigenous history in the 20th century.

Environmental historian Sean Kheraj (York University) describes how one mammal species bounced back in a Europeanized environment.

Key Points

- Indigenous people experienced the arrival Euro-Canadian agriculture and other industries as a process that alienated land and food resources, as well as traditional spaces with more complex meanings.

- European food cultures have been historically incompatible with Indigenous food resources.

- The mega-projects of the 20th century displaced permanently large numbers of Indigenous peoples by utterly destroying their landscapes.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.3 long description: Herd of buffalo at the foot of a mountain. The photo is of a photo beside a slip of paper. The paper, written on a typewriter, says “Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year (1900) nineteen hundred, by Joseph Rouer Roy, at the Department of Agriculture.” [Return to Figure 11.3]

Media Attributions

- Bush Camp © Paul Kane is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Mars Team Online, accessed February 1, 2016, http://quest.nasa.gov/mars/background/terra.html. ↵