Chapter 2. Confederation in Conflict

2.14 Summary

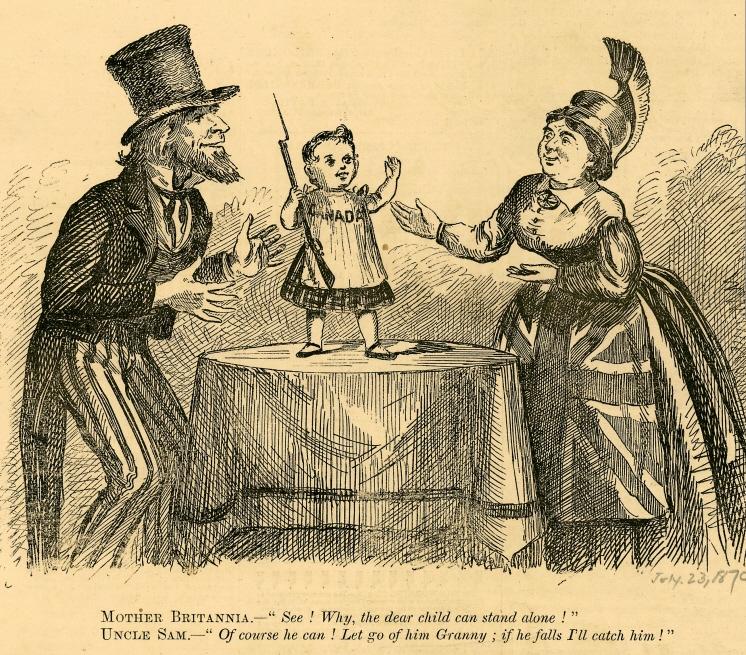

UNCLE SAM.—”Of course he can! Let go of him Granny; if he falls I’ll catch him!” In 1870, Canada annexed the West (almost at bayonet point), but was it strong enough to stand on its own or would it collapse in its infancy?

The first decades after Confederation were not easy. While it is true that the federation expanded quickly to cover almost the whole of the northern half of the continent, it did so in a way that provoked conflict and division. The record of additions is straightforward. In 1870 Manitoba signed on and British Columbia followed in 1871. Prince Edward Island returned to the table and settled its issues with Ottawa in 1873. Elements of the North were added on quietly as Britain shuffled further and further away from being an imperial presence in the Western hemisphere. Against these achievements, one has to recall that from 1867-1869 Nova Scotia wriggled on the hook of Confederation; from 1869 through most of 1870 the fate of the Northwest was uncertain. The Canadian presence at Red River was led by men unafraid of violence and they were met by force as well. Blood was shed and an antipathy grew between Ontarians and Manitobans (especially the Métis). The 1873 Pacific Scandal created serious doubt on the likelihood of an all-Canadian route for a railway to the West — let alone to British Columbia. BC’s demands for the Terms might have seemed to Ottawa like petulance, but it threw further into doubt the prospect of the Confederation lasting even one generation. The 1880s witnessed the return of Louis Riel and armed conflict across the Prairies. The government would exploit its ability to deliver troops into the thick of the second Northwest uprising to vindicate the railway project, but the mishandling of Métis complaints and the treaties looked bad. The hanging of Riel did nothing, of course, to reassure Quebec that Canada was anything more than an Anglo-Ontarian and Orange project in which punitive raids were conducted against francophone Catholics. The 1880s also saw the return of the Nova Scotia Repeal Movement. The Bluenose anti-Confederates were tamed but their campaigns brought to the fore compelling evidence that the Maritimes were not at all better off for having become a province of Canada. It is difficult to know whether events further west informed their discontent, but it is equally challenging to imagine that they would have been reassured by separatist talk in BC and expensive wars on the Prairies.

Even Ontario — arguably the most committed to, and the chief beneficiary of, Confederation — bridled under Ottawa’s maneuvers. The Provincial Rights movement established the principle that the provinces were partners in Confederation, that they had entered into the agreement under their own free will and could, therefore, leave if need be. The “pact” or “compact” model of Confederation supplanted the “act” interpretation and, in doing so, set a path for federal-provincial relations for the next century.

The rise of Quebec nationalism in the years immediately after Confederation was to have important ramifications in the early 20th century. The abandonment of dualism as a way to build a country based on the credibility and integrity of two European cultures was a significant blow to unity. The treatment of the Métis and the vociferous tone of Orange politicians sent a powerful message to Quebec. The Orange Order’s loyalist and royalist creed sought more British-ness, not less. Quebec sought more Canadian-ness instead. This division would vex Macdonald and his successors in the decades before the Great War in 1914.

Key Terms

Beothuk: Indigenous people of Newfoundland; believed to have disappeared — due to exotic diseases, loss of territory, and armed conflict with European colonists — by the second quarter of the 19th century.

Cariboo Wagon Road: A pair of routes to the gold-bearing regions on the Interior Plateau of British Columbia, initiated in 1860. One begins in Fort Douglas, the other at Yale.

Confederation League: Founded by Amor de Cosmos and John Robson in 1868, promoting the idea of union with Canada through newspapers and direct lobbying of administrations in Victoria, Ottawa, and London. Their goals included responsible government in the colony, reciprocity with the United States, and austerity measures to address colonial debt.

disallowance: An effective veto held by Ottawa that could be used to overturn provincial legislation.

Dominion Lands Act: 1872; the legal mechanism that made possible the distribution of western lands.

Escheat Movement: An organized movement in 19th century Prince Edward Island with the objective of ending absent landlordism and the distribution of lands to tenant farmers.

Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway: 1871; the E&N was built to connect the coalfields of the central island with the British Columbia capital, Victoria.

graving dock: Also called a dry dock; repair facility for shipping.

Harbour Grace Affray: 1883 Newfoundland dispute in which Orange Lodge Protestants and Catholic neighbours came to blows; led to five deaths and a dozen casualties.

Indian Agent: An agent of the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs (or, later, DIAND) with responsibility for managing and/or supervising one or more Indigenous communities.

Kanakans: Hawaiians or Pacific Island workers; this term may have been used disparagingly or in a derogatory fashion, however, the word means “human being” in the Hawaiian language.

Medicine Line: The 49th parallel north, so named by the First Nations of the Plains because it worked as an invisible barrier to stop attacks northward by United States soldiers.

Moravian Brethren: An early Protestant sect from central Europe; established missions in Labrador, with the first permanent site established at Nain in 1771.

Nativist millenarians: Movements among mostly Indigenous peoples under imperialism that attempt to throw off their occupiers and return to an idealized past way of living; sometimes imbued with a mystical element that could involve divine intervention.

Pacific Scandal: 1873; Macdonald’s Conservative Party was given significant funds from the Canadian Pacific Railway, which caused the CPR to lose the opportunity to complete the Intercolonial Railway, cost Macdonald his administration, and brought the Mackenzie Liberals into office.

Peace, order, and good government (POGG): From Section 91 of the BNA Act as regards “residual” or “residuary powers” (granted to the Queen, the Senate, and House of Commons to make laws), and which could cover anything and everything that was either not itemized or as yet not imagined in the constitutional division of authority.

Pig War: Colloquial name for a dispute between the United States and the British Empire over the San Juan Islands, from 1859-1873.

populist: In politics, an appeal to the interests and concerns of the community by political leaders (populists) usually against established elites or minority — or scapegoat — groups. The rhetoric of populists is often characterized as vitriolic, bombastic, and fear-mongering.

scrip: A system introduced by Canada for extinguishing Métis land title, beginning in 1870. Scrip documents indicated individual entitlement to land, although not necessarily to land on which one was already settled. While the numbered treaties dealt with whole First Nations communities collectively, scrip was negotiated on an individual and household basis.

section and quarter-section (block system): The system used by land surveyors to divide land and property. One section is meant to be 1 mile square.

seigneurial system: Used in New France; based on a feudal system in which land was granted under a royalty system, and the tenant was responsible for farming the land to meet their physical needs (food, heat, and shelter). This system was abolished in 1854.

Treaty of Paris: Ended the Seven Years’ War. France ceded all of its territory east of the Mississippi to Britain (including all of Canada, Acadia, and Île Royale) and granted Louisiana and lands west of the Mississippi to its ally Spain. Britain returned to France the sugar islands of Guadeloupe. France retained St. Pierre and Miquelon along with fishing rights on the Grand Banks.

ultramontanist: Elements in Catholicism that emphasize papal authority over secular authority and, after 1870, papal infallibility. Seeks a large, extensive role for the church in daily life and objects to the main features of modernity, especially the growth of the secular state. Although ultramontanism faded in Europe after 1870, it remained a powerful force in Canada to the 1960s.

White Dominions: Former British colonies dominated by a European population or elite; includes Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Newfoundland to ca. 1934-1949.

Yale Convention: Meeting between British Columbian delegates to determine the colony’s demands as regards joining Confederation.

Short Answer Exercises

- Why did some politicians in Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and New Brunswick toy with the idea of pulling out of Confederation in the first two decades after 1867?

- In what ways was British Columbia distinct from the rest of Canada?

- What forces brought PEI to the table in 1873?

- Was the establishment of the Red River Provisional Government an act of rebellion?

- What flaws in Confederation were highlighted by the Provincial Rights movement?

- What strategies did Canada adopt in annexing the West?

- Why were First Nations prepared to sign treaties with Canada?

- What conditions led to the events of 1885 in the Northwest?

- Why was the question of Riel’s sanity so problematic?

- How did the CPR figure into Canadian expansionism?

- In what ways were the lives of Northerners changing in the period between 1867-1930?

- What were the distinguishing features of life, economy, and politics in Newfoundland before the Great War?

Suggested Readings

Keough, Willeen. “Contested Terrains: Ethnic and Gendered Spaces in the Harbour Grace Affray,” Canadian Historical Review, 90, no. 1 (March 2009): 29-70.

McCoy, Ted. “Legal Ideology in the Aftermath of Rebellion: The Convicted First Nations Participants, 1885,” Histoire Sociale/Social History, 42, no. 83 (Mai-May 2009): 175-201.

Miller, J.R. “Owen Glendower, Hotspur, and Canadian Indian Policy,” Ethnohistory, 37:4 (Fall 1990): 386-415.

Milloy, John. “’Our Country’: The Significance of the Buffalo Resource for a Plains Cree Sense of Territory,” in Kerry Abel and Jean Friesen, eds., Aboriginal Resource Use in Canada: Historical and Legal Aspects (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1991): 51-70.

Read, Geoff, and Todd Webb. ‘The Catholic Mahdi of the North West’: Louis Riel and the Metis Resistance in Transatlantic and Imperial Context,” Canadian Historical Review, 93, no. 2 (June 2012): 171-95.

Waite, P.B. “Canada in 1874: An Overview,” in Arduous Destiny: Canada 1874-1896 (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 1971): 1-12.

Media Attributions

- Canada, Britannia, and Uncle Sam © McCord Museum (M993X.5.1039) is licensed under a Public Domain license