Chapter 2. Confederation in Conflict

2.3 British Columbia and the Terms of Union

Nowhere was the ambition of the new Dominion more evident than in the recruitment and securing of British Columbia as the sixth province in 1871. Canada had not yet subdued and annexed Manitoba when it turned its attention to the Pacific Slope. As the crow flies, the nearest settlement of any size would have been Kamloops — 2,000 km west of Winnipeg with no road in place. By sea, in the days before the Panama Canal, it would involve a voyage of more than 13,000 nautical miles from Halifax to Victoria via Cape Horn. Annexing islands in the West Indies would make more sense logistically, as would making British Honduras (now called Belize) a province (an idea that was touted from time to time). Canadian interest in the farthest west carried forward themes that can be found in all the other annexations, but it reflects unique interests as well. Why British Columbians decided to join a remote and essentially alien federal state is perhaps less obvious.

A Big Country

British Columbia’s boundaries in 1867 were a little uncertain, especially concerning Alaska and the Peace River valley. Nevertheless, even the most constricted view of its geography at the time would make it the largest of the British North American colonies and also the most sparsely populated. This points to one of the paradoxes of BC: It is a big area with few people, but the population is more tightly concentrated than is the case elsewhere in North America.

Topography and resources tell the tale. Narrow mountain valleys, canyons, deep coastal fjords, and one range of towering peaks after the next meant that options for settlement sites (before and after contact) were limited, and the colony’s geology was exposed and invited exploitation. It created conflicts as well, given that the Indigenous population was large in the 1860s (especially before the smallpox epidemic of 1862-1863) and the European tide demanded access to cleared and arable land.

There was a long list of gold rushes in the 1850s-1860s in the mainland colony, and these did much to shape the character of the colonial administration. Gold found in the Queen Charlotte Islands (aka: Haida Gwaii) led to very limited intrusion, but the mainland was far more penetrable. The first discoveries near Kamloops were followed up by the more famous and lucrative placer opportunities along the Fraser and the Thompson rivers in 1858. At around the same time, smaller pockets of activity appeared along the Similkameen River, near what is now Allenby (near Princeton), at Rock Creek (east of Osoyoos), and in the Peace River district. The largest strike was made in the heart of the Cariboo in 1861, centred on Barkerville. There were other, less noteworthy gold rushes along the Stikine River in the same year and in the Shuswap district shortly thereafter. In 1864-1865, mining operations appeared at Leechtown (west of Victoria), Cherryville (east of Vernon), at Fisherville (near Fort Steele), and on the Big Bend of the Columbia River. The Omineca Gold Rush launched in 1869, and there was a small rush into the Burnt Basin near the Kettle Valley. In short, the colonial map was dotted with gold finds and compact and energetic mining centres. In addition, service communities sprang up to feed and fleece the miners, including everything from cattle ranches to dance halls.

The distribution of these new towns presented administrative challenges for the colonial regimes. Civil suits at the local level constituted an important part of a decentralized system of government. Itinerant jurists and local county courts were important features of life in a colony with a very high homicide rate, a sobering track record of public hangings, and predictable conflict over competing claims to mining leases and other property.[1] Until 1866, the mainland was governed from New Westminster; thereafter, the colonies of British Columbia (the mainland) and Vancouver Island were united and governed from Victoria. The distance between the capital and Barkerville is 900 km — a longer and rougher road than that between Fredericton and Montreal. The Big Bend, Cherryville, Fisherville, and the Similkameen were all more easily accessed from the Washington Territory (later Washington State). Indeed, Rupert’s Land was easier to reach from the Kootenays than the Kootenays were from the coast. The existing transportation infrastructure was limited. There was a wagon road system between the Fraser Canyon and the Cariboo; paddlewheelers worked the Shuswap and the coastline, but the inland systems were susceptible to freeze-up and to violent seasonal fluctuations in water levels, and the coastal network was exposed to storms. The ability to assert colonial authority under these circumstances was limited, although symbolic efforts were repeatedly made.

A Vulnerable Colony

Building the Cariboo Wagon Road had effectively bankrupted the united colony of British Columbia. It was the first of what would be many government subsidies to private enterprise, the hope being that royalties and license revenues would offset the heavy capital investment in infrastructure. Another was the graving dock at Esquimalt that made the Vancouver Island port, in the calculations of the Royal Navy, even more critical.

The heavy capital investment at Esquimalt had the added benefit of increasing interest in the coal mines at and around Nanaimo. Industrial production in the Victoria area was on the increase as demand grew for chains, saw blades, and nails. Logging was well underway in several locations, including the Burrard Inlet nodes of Port Moody, Moodyville, and Stamp’s Mill, that harvested what were reckoned to be some of the largest trees on earth. This steam-powered economy further stimulated the collieries and reinforced connections with markets in California, Hawaii, China, Mexico, and Chile. Virtually nothing, at this time, was exported to Canada. Given the prevailing winds of the Atlantic, Liverpool was regarded as closer to British Columbia than Quebec City; therefore, that’s where the sea traffic gravitated.

That is not to say that Canada did not exercise any influence on the colony. It did so in a variety of ways. First, like the rest of British North America, British Columbia had a fraught relationship with the United States. The boundary with the American territories to the south was established in 1846, but the fear remained that American gold-seekers were probing for weaknesses and opportunities to see the BC mainland annexed to the American republic. Likewise, the dispute over the San Juan Islands (known colloquially as the Pig War) percolated along from 1859-1873. The American purchase of Alaska in 1867 was an additional reminder to the local colonial regime that the United States was not merely talking about a manifest destiny, it was acting on it. In this light, British Columbians saw the welcoming arms of Canada as a refuge from American imperialism, although they preferred the idea of continuing with the Royal Navy and British power.

Canadians in British Columbia

The gold rushes brought to the West Coast a complex mix of peoples. The multitude of Indigenous peoples and nations were invaded by thousands of Americans (Euro- and Afro-), Chinese, Europeans (including British, of course), as well as Mexicans, South Americans, Hawaiians (aka: Kanakans), and fortune-hunters from even further afield. They also attracted Canadians, Nova Scotians, New Brunswickers, and a few Prince Edward Islanders. Two of these — Amor de Cosmos (a Nova Scotian) and John Robson (a migrant from Canada West) — brought their journalistic careers to the Far West. They also undertook political careers that echoed the language of eastern BNA. Together they were founders of the Confederation League in 1868, using their newspapers to promote the idea of union with Canada while directly lobbying administrations in Victoria, Ottawa, and London. Meeting at the Yale Convention that year, they set out their goals: responsible government in the colony, reciprocity with the United States, and austerity measures to address colonial debt. The British-appointed Governor, Frederick Seymour (1820-69), was cool to these ideas; his successor, Anthony Musgrave (1828-88), less so. Musgrave had served as Governor of Newfoundland when its assembly failed to endorse union with the rest of British North America. He had made mistakes and wasn’t about to repeat them on the West Coast.

The Canadians’ position was further helped by fears that a Fenian invasion was pending. Beginning in 1866, it was believed that Fenians were mustering in San Francisco with the goal of completing the American coastline from California to Alaska. Pro-annexationist voices in the colony were muted, however, until an Annexationist Petition was sent to Washington, DC in 1869 by a group of Victorian merchants. Their audacity in this regard served to increase support for the Confederation League.

By this time, it was clear to British Columbians that Britain could not be trusted not to abandon the colony. “I do not know why,” wrote one British emigration officer in London to his superior,

…we should go out of our way to lead settlers to make an erroneous choice…. I by no means agree that it is good general policy to try to swell the English population in B. Columbia [sic]. The fewer Englishmen that are committed to the place, the better it may prove to be in no distant times. As to hoping that we can by Emigrants round Cape Horn outnumber the natural flow of Emigrants from California and the United States, one might as well make the old experiment of keeping out the Ocean with a mop.[2]

Britain’s commitment to the Pacific Coast continued to shrink. Pressure grew to consider the Canadian option.

The Terms of Union

Governor Musgrave selected a delegation to send to Ottawa, consisting of: Dr. R. W. Carrall, a physician from Goderich, Ontario, who had practiced in Nanaimo before moving to Barkerville in the late 1860s; Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works, Joseph Trutch, an Englishman with a familial connection to Musgrave; and Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, a Londoner, another physician, and a holdover from the days of the HBC. The party had significant interests in the outcome of the talks with the Canadians. Helmcken, for his part, played the role of delegation skeptic. He said that British Columbia “had no love for Canada; the bargain for love could not be,” and was more inclined to continuing with the status quo.[3] Carrall was an enthusiastic supporter of Confederation and the whole concept of the Dominion. As a Cariboo resident, he had a keen sense of the necessity for improved infrastructure and of its cost. Trutch, for his part, was a career administrator who was concerned that Ottawa would oblige Victoria to make concessions to the Indigenous people — for whom he had a very low regard, even by contemporary standards. Unlike the Confederation League, these men were never enthusiastic supporters of responsible government.[4]

The deal they struck with Ottawa included elimination of the colony’s debt, funding for the graving dock at Esquimalt, and the building of a railway from Canada to the West Coast, the construction of which was to be complete within ten years (see Section 2.9 for more details). The Canadians accepted an inflated population figure for the colony (on which financial and electoral issues would be based), but not as inflated as the delegation proposed. Ottawa was careful, as well, not to wade into the murky local debate over responsible government and colonial handling of Indigenous affairs, and so left both to the British Columbian administration to resolve in its own time. On the last point, the language of the British Columbia Terms of Union, 1871 (the Terms) suggests that Trutch very effectively misrepresented his approach to reserve lands:

[Article] 13. The charge of the Indians, and the trusteeship and management of the lands reserved for their use and benefit, shall be assumed by the Dominion Government and a policy as liberal as that hitherto pursued by the British Columbia Government shall be continued by the Dominion Government after the Union.[5]

Ottawa’s hands were now tied; successive administrations in Victoria would monitor Indigenous policies to ensure that they were “as liberal” as Trutch’s, but not more so.

With the Terms in hand, the British Columbians were inclined to watch their Canadian suitors closely. The delegation had hoped for a wagon road; they were promised a railway. The Canadians were clearly motivated by both their own faith in modern infrastructure and the economic opportunities it presented, on the one hand, and on the demonstrable advantage a railway to the West Coast would lend them in terms of territorial conquest. No one, however, had given sufficient thought to the business of crossing the Rockies and reaching the coast. They had given themselves a decade to get it done and the clock was ticking loudly in British Columbia from the very start.

Nothing but the Terms

Resistance to the whole idea of Confederation was perhaps strongest among the old British elite in Victoria and New Westminster. These were people with strong HBC ties and few connections to Canada. They were also staunchly opposed to responsible government. Individuals like the province’s Senators, Clement Cornwall (the owner of Ashcroft Manor) and W. J. Macdonald, allied with Edgar Dewdney (MP and colonial road-builder) to warn John A. Macdonald of the problems brewing in BC politics. Even the province’s limited male suffrage drew their criticisms and accusations that it had produced a populist assembly.

The present Legislative Assembly is perhaps taken together as inferior a body of the sort as could well be imagined; and if the Province is to be unmistakably [sic] given up to their tender mercies without the interposition of experienced guidance and some extent repression from Ottawa, no thoughtful mind can view the picture without the gravest apprehension.[6]

However appalled the senators and the MP may have been, the Assembly looked far more British than Canadian. British North America-born politicians remained a minority in the Legislature until the 20th century. According to mid-20th century historian, Walter Sage, Canadians were regarded contemptuously as tight-fisted spendthrifts who were more likely to send money home to families in the East than leave it in the local stores.[7] Confederation delegate Dr. Helmcken shared some of this anti-Canadian sentiment. He recognized that British Columbia’s loyalty to Canada would come only with material benefits and, perhaps, with time. “Love for Canada,” he wrote in 1870, “has to be acquired by the prosperity of the country, and from our children.”[8]

Prosperity and advantage were key to retaining British Columbia’s involvement in the Canadian project; the stage was set for wrangling over the progress of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Key Points

- British Columbia was a sparsely populated, geographically huge colony with concentrated settlements that were mostly devoted to mining.

- Size and the expense of building roads, as well as fear of American expansionism, turned the colony toward the Canadians.

- British Columbia’s willingness to join the Dominion depended on the construction of a trans-continental railway, Ottawa’s absorption of colonial debt, and funding for a dry dock on Vancouver Island.

Media Attributions

- View of Nanaimo Harbour showing the bastion and shipping © Howard King, British Library is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Stó:lō woman with a cedar basket © Royal British Columbia Museum (PN996) is licensed under a Public Domain license

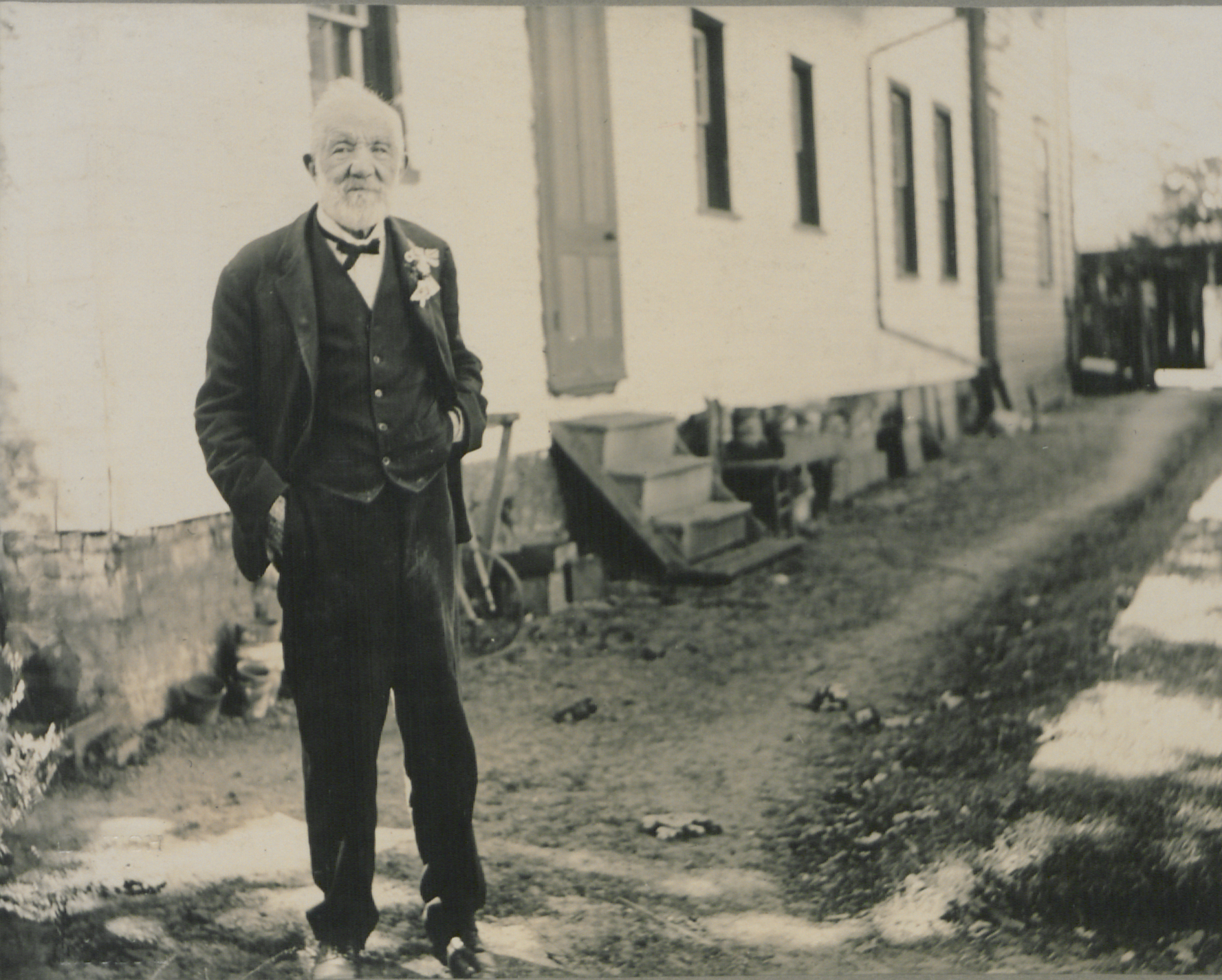

- Hon. John Sebastian Helmcken, 1917 © Walter W. Daer is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tina Loo, Making Law, Order and Authority in British Columbia, 1821-1871, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994). ↵

- Letter from T.W. Murdoch to F.F. Elliot, 26 April 1867, (marginal notes), Public Records Office, Colonial Office 60 (30), Kew, UK. ↵

- Quoted in Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto:University of Toronto Press), 346. ↵

- Jack Little, “Foundations of Government,” The Pacific Province: A History of British Columbia, gen. ed. Hugh J.M. Johnston (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1996), 88-91. ↵

- Senate of Canada, Article 13 of Schedule: Address of the Senate of Canada to the Queen, in British Columbia Terms of Union (UK: Court at Windsor, 16 May 1871), accessed 13 May 2016, https://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/bctu.html. ↵

- Draft of a Memorandum from Cornwall, Macdonald, and Dewdney to Sir John A. Macdonald, sent 7 May 1879, quoted in Hamar Foster, “The Struggle for the Supreme Court: Law and Politics in British Columbia, 1871-1885,” Louis A. Knafla, ed., Law and Justice in a New Land: Essays in Western Canadian Legal History (Calgary: Carswell Legal Publications, 1986), 168. Emphasis in original. ↵

- Walter N. Sage, “British Columbia becomes Canadian, 1871-1901,” Historical Essays on British Columbia, Jean Friesen and Keith Ralston, eds. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976): 58. ↵

- Quoted in ibid.: 57. ↵

A pair of routes to the gold-bearing regions on the Interior Plateau of British Columbia, initiated in 1860. One begins in Fort Douglas, the other at Yale.

Also called a dry dock; repair facility for shipping.

Colloquial name for a dispute between the United States and the British Empire over the San Juan Islands, from 1859-1873.

Hawaiians or Pacific Island workers; this term may have been used disparagingly or in a derogatory fashion, however, the word means “human being” in the Hawaiian language.

Founded by Amor de Cosmos and John Robson in 1868, promoting the idea of union with Canada through newspapers and direct lobbying of administrations in Victoria, Ottawa, and London. Their goals included responsible government in the colony, reciprocity with the United States, and austerity measures to address colonial debt.

Meeting between British Columbian delegates to determine the colony’s demands as regards joining Confederation.

In politics, an appeal to the interests and concerns of the community by political leaders (populists) usually against established elites or minority — or scapegoat — groups. The rhetoric of populists is often characterized as vitriolic, bombastic, and fear-mongering.