Chapter 2. Confederation in Conflict

2.7 Rebellion 1885

After the Canadians arrived in Red River, much of the local Métis population departed. Canadian failure to respect the scrip they issued to the Métis for land was one factor, as was the virulent hostility of Orangemen outraged at the “martyrdom” of Thomas Scott. The Métis had options and there were many other communities on the Prairies to which they might turn. The most promising of these were arranged along the Saskatchewan River, particularly the South Branch.

Métis Discontent

By 1875, Canadians had pretty much over-run the old Red River colony and Winnipeg was, for all intents and purposes, a Canadian city. More Métis, disenchanted with the ways in which the Canadian regime neglected to address the issue of land entitlement, drifted toward the Saskatchewan Valleys. There were just enough bison left on the plains in the mid-1870s to create hope among the Métis that at least one aspect of their old livelihood might continue. They established new farms – made up of long and narrow strips that were a legacy of the seigneurial system in New France – and erected churches and other elements of established communities. The most important settlements were Qu’Appelle, Duck Lake, and Batoche. It wasn’t long before Canadian surveyors arrived in the region and began redrawing local maps along the square section plan that had, in 1869, caused unrest to erupt in and around Red River.

In 1884, the dissatisfied and worried Métis of the South Saskatchewan sought out Louis Riel.

Riel after 1870

The life and times of Louis Riel are dominated by his two confrontations with the power of Ottawa and the ambitions of Canada. It is easy to lose sight of the fact that he was very young in 1869, and a persecuted and confused man entering middle age in 1885.[1]

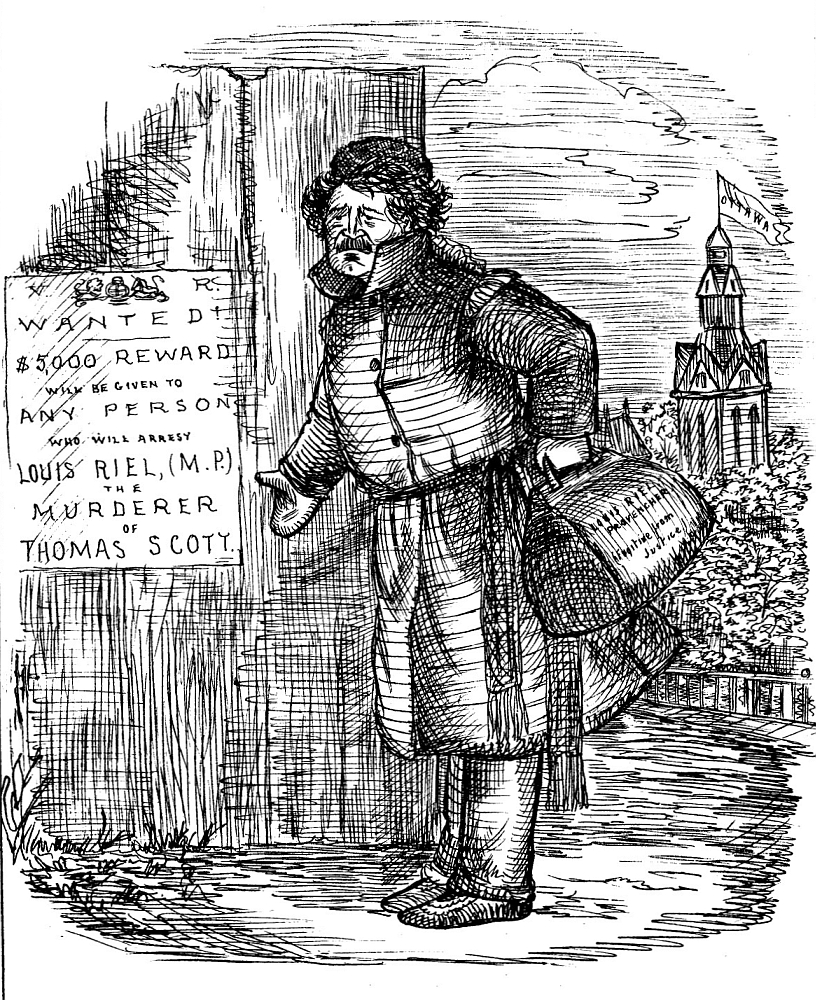

Soon after negotiations with Canada were concluded in 1870, Riel decided to flee to the United States. He was only a few steps ahead of the Ontarian Orangemen who had volunteered for regiments that staggered toward Manitoba with a vendetta — for Riel’s execution — in mind. On three occasions he was elected by voters in the West to represent them in the House of Commons in Ottawa; fearing for his life, he never took his seat.

Macdonald, eager to avoid a rupture in Canada, sent Riel money to remain in the United States. He was granted amnesty, provided he stayed out of Canada for five years. But Riel suffered a mental health collapse and travelled to Quebec where he was a patient in two asylums. In one, according to historian Dan Francis, Riel’s treatment was brutal:

He was routinely trussed up in a straitjacket because of his violent behaviour. He was allowed to exercise only under guard in the yard behind the main building and, he complained in a letter, ‘I spend the night with chains around my feet and hands.’ [2]

He thereafter joined a Métis community in Montana — the American Northwest and Pacific Northwest was peppered with such enclaves, some of which dated to the 18th century. He married a Métis woman (Marguerite Monet, née Bellehumeur) and they had three offspring, none of whom survived childhood. Riel’s mental health issues may not have been fully resolved, as he announced that he was receiving visions of a sovereign Métis state in the Prairie West. He wrote prolifically, taught at a Montana school, joined the Republican Party and took out American citizenship. In June 1884, Gabriel Dumont (1837-1906) arrived with a delegation of Métis, anglophone country borns, and Canadian settlers. They persuaded Riel to return to Canada (that is, to the Northwest), and initiate a new round of negotiations with Ottawa. Riel agreed, with conditions. It would dawn on Dumont and the rest of the delegation only later that Riel was not the man he had been in 1870.

From Protest to Rising

At the start, Riel demonstrated good organizational skills and made use of key personnel. He set about building a coalition of disaffected peoples on the Prairies. Under Riel’s leadership and by the hand of Canadian settler William Henry Jackson, the communities of the area around Prince Albert produced a petition calling for: relief to the Indigenous peoples, land disbursements to the Métis, easier access to additional lands for homesteaders, free elections, and the establishment of new provinces with rights at least as great as those of Manitoba. Riel and his allies would dress this up in the language of “loyal British subjects” so as to douse the idea that this was a document produced by people who rejected Ottawa’s rule.[3]

In March 1885, after three months and with no reply from Ottawa, the coalition took its next step. As was the case 15 years earlier at Red River, they established a Provisional Government. Within a week Dumont’s troops engaged a body of 53 NWMP, along with more than 40 volunteers in the Prince Albert militia, on a snowy road between Fort Walsh and Duck Lake. The skirmish lasted barely 30 minutes and the NWMP/Volunteer casualties were severe: a dozen dead and another eleven injured. The Métis lost five, including Dumont’s brother, Isadore, and the Cree leader Assiwiyin. The small battle set off a panic among the NWMP, who withdrew from the Saskatchewan River Valley in haste. Even if their strategy was badly underdeveloped, at this stage the Métis had established a considerable advantage over Canada. Duck Lake was enough to instigate a Canadian military response but it was soon eclipsed by events at Battleford and Frog Lake.

Indigenous unrest finally spilled over. A farming instructor was murdered on the Mosquito Reserve and the northern Cree leader, Pitikwahanapiwiyin (aka: Poundmaker, 1842-1885), marched his followers and some Nakoda (aka: Stoney) Sioux into Battleford on 30 March. The town was abandoned by alarmed settlers and the Indian Agent was unwilling or unable to offer the Cree-Nakoda protest group any food or resources. Looting of empty homes followed. At Frog Lake on 2 April, Mistahimaskwa’s Cree broke with their moderate leader and attacked and killed nine settlers, including the Indian Agent. Two weeks later Fort Pitt was captured, although this time without bloodshed.

The tide was about to turn violently against the Métis and First Nations forces. Only one day after the battle of Duck Lake, news of the incident reached Ottawa via the new telegraph technology that paralleled the Canadian Pacific Railway line. This was one feature of a technological revolution that had taken place on the Plains since the Red River resistance. Macdonald had barely to request volunteers for militia duty: local newspapers across Canada, from Fort William to Sydney, were calling for and sponsoring local regiments. The troops who showed up to head west were proof of how a “Canadian” sentiment was growing across the former separate (and sometimes rival) colonies; they were also proof of a badly underdeveloped Canadian military. Each regiment wore colours associated in some way with their home communities rather than with a national regiment, let alone an army. Two weeks after call-up, about 8,000 soldiers (almost all of them inexperienced) were boarding trains and speeding west. The ability to do so had not been there in 1870; Riel’s failure to cut the rail line or telegraph line suggests that he did not appreciate the extent to which the world had changed since Red River.

Major-General Frederick Middleton and Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter led a two-pronged attack on the Cree-Nakoda forces and the Métis Provisional Government headquarters at Batoche. Over three days, from the 9th through the 12th of May, Middleton’s Winnipeg Militia pounded away at the Métis position. Vastly outgunned, the Métis nevertheless held out until their ammunition was exhausted. In a battle that was reminiscent of the Métis-Sioux clash at Grand Couteau in 1851 and foreshadows the Belgian theatre of war in 1916-17, the Métis sharpshooters picked off their enemies from a series of trenches dug in preparation for the assault. As the Métis resistance failed, many of their troops and leaders fled. Three days after the battle, Riel surrendered to Middleton. He would be tried, convicted, and hanged in Regina.

The Cree vs. Canada

The resistance to Canadian ambitions in the West was not over. Otter’s troops performed less well against the Cree: at Cut Knife Hill and Eagle Hills, and at Frenchman’s Butte and Loon Lake, the Cree scored significant victories. However, the Canadians were wearing them down. The leadership status of Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa was compromised when they surrendered on 26 May and 2 July respectively.

In the 1885 trials that followed in Battleford, the outcomes for the Indigenous leadership were particularly bad. Eight men — among them Kapapamahchakwew (aka: Wandering Spirit), and the two Nakoda leaders, Itka and Man Without Blood – were tried in October and condemned to hang. Some traditional Plains cultures believe that the soul is located in the neck and so the idea of hanging was especially horrific. One of the condemned men unsuccessfully requested death by firing squad instead. A gallows large enough to hang eight men at once was built and the mass execution took place on 27 November. The fate of Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa (considered in Section 2.8) was only slightly better.

In the aftermath of the executions, many Cree and Nakoda fled to the United States. While the story of Sitting Bull and the Dakota Sioux’s flight into Canada is relatively well known, the fact that a couple of hundred Indigenous people from the Canadian Plains thought themselves safer south of the Medicine Line is not.[4]

Key Points

- Canadian disregard for the Métis, country-born, and Indigenous peoples in the West led to diplomatic and then armed conflict in 1885.

- Louis Riel was recruited by a delegation from Saskatchewan to lead a second protest against Ottawa.

- In March 1885 violence erupted involving several different and not unified groups.

- The Canadians now had the ability to transmit information via telegraphs and to expeditiously move troops to the West, and were thus able to suppress the rebellions.

- The leadership of the Cree and Nakoda Sioux were punished severely for their role in these events, effectively crushing the likelihood of further Indigenous resistance in the region.

Long Descriptions

Figure 2.10 long description: Louis Riel, lounging on the ground, looking solemn: “Gabriel, God has revealed to me that the church’s teachings regarding hell are false.” Gabriel, shooting at the enemy using a blind, one of several men in trenches, shooting: “Is that so?” Sound effects like BLAM and “pk pk” represent explosions and shooting. [Return to Figure 2.10]

Figure 2.11 long description: Louis Riel in Ottawa, reading a poster that says “Wanted! $5,000 reward will be given to any person who will arrest Louis Riel, (M.P.) the murderer of Thomas Scott.” Riel is carrying a carpet bag that says “Louis Riel, Provencher, Fugitive from Justice” while holding a mittened hand out in askance, looking rather put out. [Return to Figure 2.11]

Media Attributions

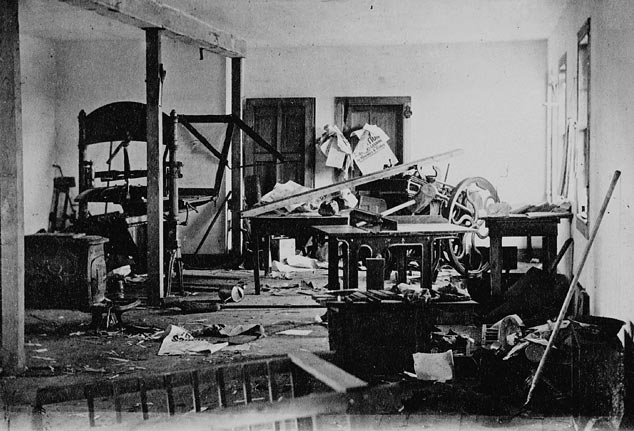

- The press room in The Manitoban printing office after the riot during the election © James Penrose, Library and Archives Canada (PA-165779) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Louis Riel © Chester Brown is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- The Science of Cheek, No. 45 © J.W. Bengough is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Men of the Halifax Provisional Battalion crossing a stream © Library and Archives Canada (C-005826) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- A very good survey of the many historical representations of Louis Riel is Douglas Owram, “The Myth of Louis Riel,” Louis Riel: Selected Readings, ed. Hartwell Bowsfield (Mississauga: Copp Clark Pitman, 1988): 11-29. ↵

- Daniel Francis, “Sane or Insane? The Case of Rose Lynam”, Reading the National Narrative, http://www.danielfrancis.ca/content/sane-or-insane-case-rose-lynam, accessed 15 May 2015. ↵

- Jennifer Reid, Louis Riel and the Creation of Modern Canada: Mythic Discourse and the Postcolonial State (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 18. ↵

- Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser, Loyal till Death: Indians and the North-West Rebellion (Calgary: Fifth House Publishers, 1997), 222-5. ↵

A system introduced by Canada for extinguishing Métis land title, beginning in 1870. Scrip documents indicated individual entitlement to land, although not necessarily to land on which one was already settled. While the numbered treaties dealt with whole First Nations communities collectively, scrip was negotiated on an individual and household basis.

An agent of the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs (or, later, DIAND) with responsibility for managing and/or supervising one or more Aboriginal communities.