Chapter 5. Immigration and the Immigrant Experience

5.8 Race, Ethnicity, and Immigration

Canada’s immigration boom was made possible and made necessary, simultaneously, by the spread of the industrial economy and mechanized transportation. The late 19th century delivered the wherewithal to move large numbers of people faster, further, and in far greater safety than ever before; there was also a rising demand for grain to feed factory towns and coal to feed industry’s furnaces. These economic and technological developments happened to come along at the very moment that racism became a much more powerful way of looking at the world. To say that the Canadian experience included elements of racism is a little like saying that the Canadian Pacific Railway involved a little steel.

Racism is not merely a suite of regrettable or embarrassing attitudes expressed by a reliably odious share of the population at large. Racism constitutes a force in the modern world, a near- or crypto-ideological position that was broadly accepted in mainstream society as commonsensical. If one believed — as a great many did — that different races were inherently and unchangeably different from one another in terms of intelligence, morality, work ethic, personality, and health (among other qualities), and if one also believed that the mixing of races in a society or in a marriage would inevitably have the effect of diluting the strength of superior races and weakening the community overall, then policies to control for these factors were a logical consequence. The belief that race was more than a social construct obliged 19th and 20th century policy makers to erect barriers to the arrival and/or successful establishment of people belonging to “inferior” races. Racial stereotyping advanced from caricatures of 19th century Irish and Chinese immigrants to enclose Japanese and Indian arrivals, Eastern and Mediterranean Europeans, Arabs, Jews, and African-Americans. Indigenous peoples were subject to similar discrimination and that is considered in Section 11.1. Racist policies also evolved.

Cultural Demography

Through to 1914 the ethnic shape of the older parts of the country was, with a few pockets of exceptions, much as it had been 50 years earlier. White Anglo-Celtic Protestants dominated Ontario and the Eastern Townships of Quebec; while they were the clear majority, a significant Franco-Catholic population and concentrations of African-Canadians lived in the Maritimes. Quebec, of course, was overwhelmingly French and Catholic, and Quebec City especially so.

Montreal, however, was a major port of entry, and many who stepped off the ships did not proceed much further inland. Italian, Jewish, and Polish immigrants could be found in significant numbers and concentrated in specific neighbourhoods in Montreal, which was principally an English-speaking city with a large French minority. Halifax was another entry point, and it acquired diversity in much the same way. The same immigrant groups had significant impacts on the largest industrial towns of Ontario (specifically Toronto and Hamilton) not least because those cities were magnets of employment and opportunity.

The pattern from the Maritimes through Central Canada is, however, uneven. Some smaller centres — Sydney, NS, Sault Ste. Marie, and Fort William (aka: Thunder Bay) for example — attracted and retained ethnic communities while much larger cities contained remarkably little diversity. Sydney became a hub of ethnic variety for the same reason some small towns in the West — like Cumberland, Powell River, and Trail in BC and Drumheller in AB — were diverse. That is, they were all part of the emergent industrial world that globalized a particular kind of labour market. People who could work in foundries, mines, mills, and on roads and rails were circulating around the planet through increasingly sophisticated systems of recruitment, transportation, settlement, and resettlement.[1]

The West as a whole was a mosaic of immigrants from Eastern and Northern Europe. Before the War, this was instantly visible in the city, town, and Prairie skylines as onion-shaped domes and Eastern Orthodox crosses topped centres of worship from the Ontario-Manitoba border to the Rockies. While cities like Winnipeg, Regina, Calgary, and Edmonton announced their British loyalty as loudly as any other centre, they were also sites of acculturation and assimilation of non-British newcomers and the newcomers’ parallel struggle to retain pre-emigration cultural elements.

Further west, in British Columbia, diversity was visible in communities that mixed Euro-Canadians with immigrants from both Europe and Asia. The British Columbian population before the Great War was increasingly Canadian-born (even BC-born) and the share of Chinese residents was actually falling — from one-in-five to one-in-twenty between 1881-1921. Immigrants from Japan and the Punjab lifted the Asian numbers a little prior to the War. Each of these Asian communities employed different economic and social strategies in the face of systematized discrimination. Unlike virtually all other immigrant groups, Asians were repeatedly described as unassimilable; barriers to their integration thus created a self-fulfilling prophecy of Asian separateness.

The Welcome Mat

Canadians often did little to smooth the path of newcomers. Organized labour and even native farm labourers regarded most immigrants as part of a plot to reduce workers’ living standards by creating a split labour market. Anglo-Canadian homesteaders, too, demonstrated their own biases in the hiring of seasonal workers and tended to favour Canadian, British, American, and even German labour over Eastern Europeans. Some Prairie newcomers were thus frustrated in their efforts to earn enough money to meet the costs of setting up a homestead. Many turned, instead, to public works like road building and railway construction. Some — and this was true particularly of Slavic and Scandinavian immigrants — acquired a poor reputation with the railway companies precisely because they had achieved some success in farming. They made their farms a priority and framed their wage labour around the rhythms of planting and harvesting. [2] This is worth underlining: A great many rural immigrants were, nonetheless, industrial immigrants.

Nowhere was this more visible than in the mining towns of the West. In Alberta, coal mining workforces typically ran to more than 14% and as high as 25.5% Italian. Slavics (an all-purpose category that captures Russians and immigrants from the Baltic and Balkan nations) were even more numerous, constituting as much as 36% of the mining workforce in some districts. The same was true in British Columbia, where British miners were a significant factor, as were Finns, Chinese, Italians, and Americans. Employers were happy to have minority immigrants, who would work for less than the Anglo-Canadian and British miners, sometimes for a fraction of their pay. The Western Federation of Miners complained in the Sandon Paystreak newspaper that they were being pushed to the brink in the Kootenays by employers who were,

…importing cheap foreigners from the Minnesota iron ranges to displace union miners… [some employers] have it figured out that if they can run in Dagoes [Italians] at the rate of about two a day they will soon have the union locoed … if [they] can get enuf [sic] of them in, wages can be cut to a whisper and Rossland mapped as a colony of Italy. Already about 35% of the Rossland pay-roll is [Italian]….[3]

The Paystreak’s screed is not exceptional. The principal instrument for transmitting ideas of racially-inherent physical, character, and moral flaws was the newspaper press. Reporting on a devastating local fire in 1908, the Fernie Free Press assigned to the diverse community that was battling the blaze the usual (and purportedly immutable) stereotypes: measured against “the serene indifference to danger of the Anglo-Saxons” there was the Italian, “with his excitable nature and glib tongue, the Oriental, with his inherent dread of danger, and his equally great regard for personal safety, [and] the stoic Slavonian [sic]….”[4] The pulpit also played a role in this as was seen very clearly in the rise of eugenics (see Section 7.8). There were, too, nativist responses from immigrants (largely British or American) and the grown children of immigrants (providing they were White) that worked to (a) denigrate the outsider, and (b) advance the claims of the nativist to inclusion in the mainstream. This can be seen in the hostility shown toward African-Americans on the Prairies in the 1920s and 1930s by Central Europeans, whose families had themselves arrived hardly a generation earlier.

Racism thus became a bar over which some populations would attempt — with mixed results — to hurdle. Others, usually by dint of skin colour or religion, could not.

African-Americans

There are many immigrant populations in Canada who faced on arrival a dense thicket of racist attitudes. The experience of African-Americans is illuminating in this respect. Their numbers were not significant until about 1907, at which time conditions in the southern and central states deteriorated and word of opportunities on the Canadian prairies reached African-Americans struggling under Jim Crow Laws. Thirteen hundred reached Saskatchewan and Alberta in the years that followed. The government’s response was necessarily crafty because Ottawa feared stirring up diplomatic anger in Washington. As one study describes the tactics deployed,

Agents were sent into the South to discourage black migrants; medical, character, and financial examinations were rigorously applied at border points, with rewards for officials who disqualified blacks; American railways were influenced to deny blacks passage to Canada.[5]

Liberals and Conservatives alike pursued these strategies to stem the flow of African-American immigration. It was largely successful.

Chinese Communities

The post-Confederation Chinese — unlike their Cariboo gold rush predecessors — were largely drafted in to build the CPR between tidewater and the Rocky Mountains. Thereafter, some found work in the Vancouver Island coal mines but principally they settled in the cities and towns, especially along the CPR mainline. These enclaves varied tremendously in size but they hosted a familiar variety of services and institutions. Populated overwhelmingly by males (single or, if married, living there without their wives who were still in China), Chinatowns provided immigrants with employment in restaurants, laundries, and grocery outlets that served both the Chinese and the non-Chinese populations. Buddhist temples and clan halls (or tongs) provided cultural anchors while the Chinese Benevolent Association provided some degree of political coordination in what was a largely hostile, anti-Chinese environment. Chinese emigration — like most Asian out-migration in these years — was stimulated by agricultural crises at home (connected, in China, to drought) and political instability. Those pushes were paired with the prospect of making enough money in British Columbia (aka: Gum Shan) to rescue or advance family-owned farming operations in, mainly, Guangdong. A strong entrepreneurial culture was thus emblematic of the community and instruments for making capital available to members of the Chinese enclave — including the hui — were well developed.[6] Living conditions, however, were often very poor: The elements that defined the Chinese experience across Canada and distinguished it from that of European settlers included wages that were a fraction of what was earned by adult White males, overcrowded living conditions in Chinatowns, and the almost total absence of family comforts. Although Chinese market farms in suburban areas became an early and important source of food in West Coast Canadian cities, few Chinese were able to become farmers nor were they able to escape the urban neighbourhoods into which they were cast. In large urban areas and even in smaller resource-extraction towns, Chinese immigrants could be found working in the homes of others as cooks and houseboys.

Anti-Chinese Policies

Probably no immigrant group has been as heavily managed as the Chinese. Sought out as cheap contract labour, they were recruited to meet finite economic and infrastructural goals. While some Chinese arrivals saw themselves as sojourners — temporary immigrants who would return to their country of origin once they’d amassed some money — many more were in for the long haul. This was not part of Ottawa’s plan and so steps were taken to limit immigration and thus encourage return migration.

The Head Tax was the main instrument used by Ottawa to regulate Chinese arrivals down to 1923. Some 81,000 people found the wherewithal to pay this fee before it was abolished, even though it rose from $50 in 1885 to $500 in 1903. In this respect, the Head Tax initiative was a failed attempt to stop Chinese immigration. It was, however, a money-maker: It is reckoned that the Head Tax pulled in $22 million for Ottawa, which equates to more than $300 million in 2015 dollars. Not everyone in the Euro-Canadian community supported the Head Tax, though for reasons that we might now consider discomfiting. A group of Euro-Canadian women argued that reducing the Head Tax would attract more immigrants, some of whom could be employed as houseboys and cooks. The Lib-Lab Member of the BC legislature, Ralph Smith, supported this idea and one local newspaper chided him that he was worried that “his gallant wife should have to roast her comely face over the kitchen fire every day because the Chinese Head Tax makes it impossible for him to get a Chinese cook.”[7] The rate of Chinese immigration varied because of the tax and global events and, like much human movement during World War I, numbers fell. After the war, immigration resumed. By this time, however, there was growing fear among the White community of the opium trade and allegations that young Euro-Canadian women were being lured into the sex trade, what was called at the time “White slavery.” Emily Murphy — a leading figure in first wave feminism, the suffrage movement, and counted among the Famous Five — wrote a series of highly popular pieces on the drug trade and its connections with Chinatown. The Black Candle (as it appeared in book form) was one of several diatribes against the Chinese community, one that catalyzed a revision of immigration legislation.

The 1923 Chinese Immigration Act terminated legal Chinese immigration and remained on the books until 1947. This complete ban on arrivals from a specified country was uniquely and exclusively applied to the Chinese. Prejudice might stand in the way of other groups but no others were treated this way in law. What immigration occurred between 1923-1947 was illegal and much of it involved reuniting spouses and family members. The 1923 Act, introduced on the 1st of July and thus coinciding with Dominion Day, was commemorated in the Chinese community as Humiliation Day in the years that followed. (For more on this topic, see Section 5.12.)

Limits on immigration is one thing; limits on immigrants is another. Chinese populations were contained (sometimes by choice but usually by civic regulations) to small urban areas — Chinatowns. They were forbidden, in Vancouver, from purchasing homes and opening stores outside of a few blocks of the city core. Like members of some other ethnic/racial/visible groups, they were also forbidden for years from attending post-secondary institutions and specifically from pursuing degrees through the University of British Columbia School of Pharmacy, a restriction that echoed Sinophobic associations between the Chinese community and drug trafficking. Many of these constraints would survive into the 1970s and early 1980s.

Anti-Semitism

Parallels can be drawn with the Jewish community. By 1914 there were reckoned to be 100,000 Jewish-Canadians, roughly 75,000 of whom could be found in Montreal and Toronto. Not all Jewish immigrants went to cities and towns, and there were Jewish farm colonies to be found in Saskatchewan. Enclaves — ghettos without walls — could be found in Montreal and Winnipeg’s North End in particular, although they were less visible in the other major cities. Vancouver’s second mayor, David Oppenheimer, was Jewish and instrumental in founding the city’s first synagogue in the heart of the East End. The population that gravitated to that neighbourhood dispersed, however, as newer and poorer immigrants intruded and as the Jewish community became more prosperous. A new spiritual and educational hub appeared on the south side, but it was never an enclave in the truest sense. In those cities where the Jewish population was more concentrated, there was inevitably a higher degree of visibility. In largely Catholic Montreal this drew anti-Semitic attacks, especially in the 1930s with the rise internationally of rabidly anti-Semitic political movements.

The Jewish diaspora had more experience of minority status than any other immigrant group in Canada. Centuries of ghettoization in Europe along with religious and legislative oppression had strengthened the community’s instinct to erect institutions of mutual support, social welfare, and education. In Canada this meant that a designated burial ground was the first objective, followed by a synagogue, and related institutions for women, men, and children. The Zionist movement also spilled out of Europe and into Canadian enclaves. In 1919 the pro-Zion Canadian Jewish Congress was established and acted as a voice for the community as a whole. This did nothing, however, to dampen Ottawa’s hostility toward Jewish immigration in the 1930s. Fearful of anti-Semitic violence in Germany, Austria, and, indeed, throughout Central and Western Europe, many Jewish families hoped to find sanctuary in Canada. Ottawa responded by holding the door firmly shut. Through to 1939 Canada accepted fewer Jewish refugees as a proportion of total population than any other nation in the West. [8]

Early Japanese Immigration

The Japanese community began arriving in Canada in the 1890s. Like the Chinese, they participated in the coal mining frontier on Vancouver Island and were drawn to the cities. In Vancouver, Chinatown and the Japanese enclave were only two city blocks apart. One important distinction, however, was the important role that Japanese immigrants played in the fishing industry, principally as owners and operators of fishing vessels. While Chinese men and Indigenous women laboured in the late 19th and early 20th century canneries, much of the fishing fleet depended on Japanese captains and crews.

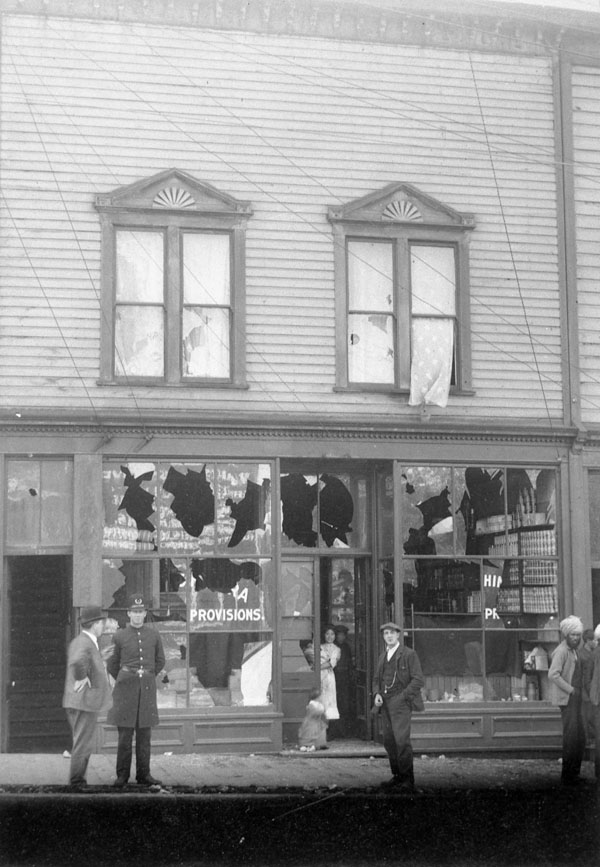

Like the Chinese, Japanese immigrants faced discrimination when it came to immigrant recruitment and host community hospitality. Public opinion among the non-Asian population was against them, as was demonstrated in a 1907 window-smashing and head-bashing riot led by the Asiatic Exclusion League (in which organized labour played a key role) that swept through the Chinese and Japanese quarters. This followed on the arrival of more than 8,000 Japanese newcomers earlier in the same year and the prospect of an Indian/Sikh migration north from Washington State. Heightened pressure from the non-Asian community caused the Canadian government to negotiate with Japan a Gentlemen’s Agreement (aka: the Lemieux-Hayashi Agreement) in 1908. This pact restricted the number of people leaving Japan for Canada. It capped the number of men who could travel to Canada, but it left open the possibility of female migration across the Pacific by not restricting the emigration of wives. The phenomenon of “picture brides” developed from there and in the decades that followed, significant numbers of women relocated from Meiji Japan to Canada where they met, for the first time, their husbands. The picture brides endured lives with men who were hitherto strangers, many of them living in small fishing or other resource-extraction communities on the northwest coast; despite powerful Meiji traditions of female submissiveness, some women sought their own path and abandoned prescribed gender roles.[9] As for the host community, Euro-Canadians were mostly hostile to the prospect of Japanese-Canadian family formation and the likelihood of growth from natural increase. What is more, Japanese success in the fisheries was so remarkable that new anti-Japanese restrictions on commercial fishing licenses were introduced in the 1920s. The 1923 Immigration Act extended new constraints to human movement between Japan and Canada to such an extent that Japanese migration was effectively as limited as that of the Chinese. The wartime and post-War experience of the Japanese-Canadian community is explored in Sections 5.11 and 6.17.

Immigration from the Indian Subcontinent

The third group to arrive from Asia came mainly from the Punjab. The Sikh migration is another in which males vastly outnumbered females. In each of these cases — China, Japan, India — Britain’s relationship with the source country is important. Of the three, only India was a British colony and that factored into the treatment meted out to potential and eventual immigrants. It also informed the Indian community’s strategies and tactics when it came time to fight for rights or survival.

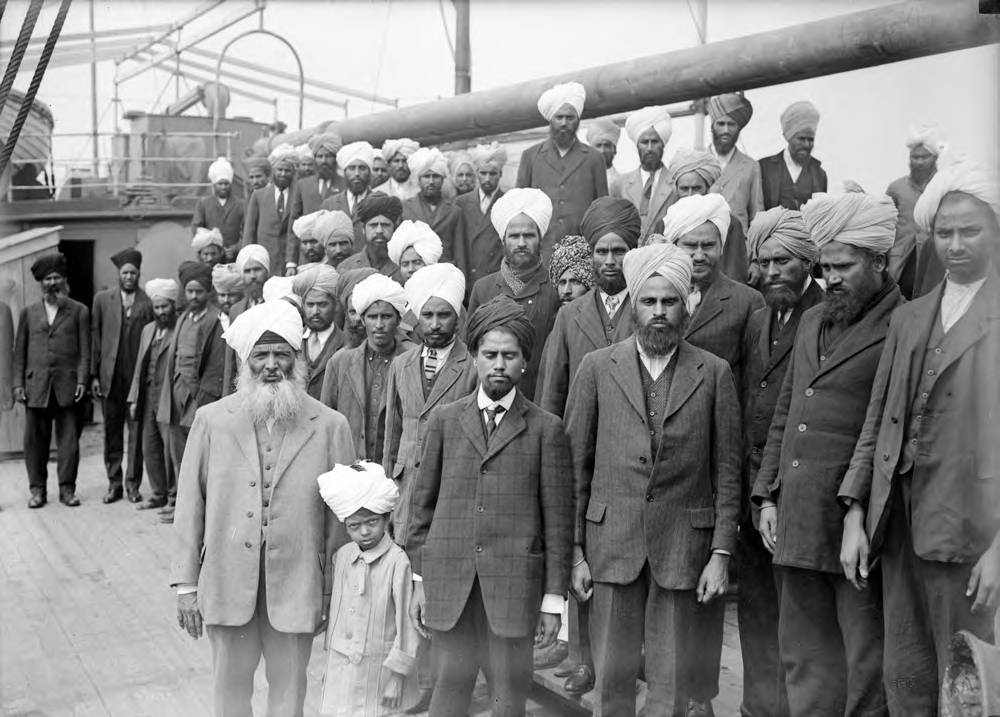

Neither a Head Tax nor a Gentlemen’s Agreement were possible in the case of India, so the method used to block migration was the continuous voyage requirement of the amended Immigration Act of 1908. Immigrants would be allowed from India (or Japan) into Canada if they could demonstrate that their vessel had travelled directly to a Canadian port without putting into another foreign harbour along the way. Given the distances involved and the ships of the time, this was effectively a barrier to Indian immigration. Sikh nationalists like Gurdit Singh (a merchant based in Singapore) accepted this challenge, chartered a vessel — the Japanese Komagata Maru — and, in 1914, attempted to bring nearly 400 potential immigrants to Vancouver. The ship was kept in harbour for two months. The passengers seized control of the ship from its Japanese crew and waited as lawyers for the Crown argued that the immigrants had departed from Hong Kong, not India, and so were in breach of the continuous voyage requirement.

The Komagata Maru incident is complex in that it draws together many different threads. Some of the parties involved were anti-British and sought Indian independence; the British, for their part, were anxious about divisive Indian politics just as tensions with Germany were becoming greater; Singh — in concert with Indo-Canadians — wanted to challenge the continuous voyage requirement just as much as he wanted the immigrants to succeed in reaching Canada; the British were as interested in putting down anti-colonial upstarts as they were in blocking immigration to Canada. Euro-Canadians, for their part, demonstrated little sympathy for the passenger/migrants and seemingly held fast to their desire for a “White Canada Forever.”[10] The Komagata Maru was driven from Vancouver harbour by the courts. Its passengers returned to India only to face jail and death at the hands of the British authorities.

Anxieties about the Indian population before the war were rooted in the White community’s racist and xenophobic perspective on the world. Even so, it is in some respects a challenge to understand. There were, in 1911, fewer than 3,000 Indians in Canada and that number was roughly half of what it had been only five years earlier. Rather than posing a demographic threat, the community was in something like free fall. It was a fear of being overrun and outnumbered that motivated many racists at the time. H. H. Stevens, the Conservative Member of Parliament who played a key role in the Komagata Maru affair, for example, was terrified that Asian populations had a much higher fertility rate and an almost endless stockpile of potential emigrants on which to draw. Stevens would prove to be a lifelong opponent of any kind of Asian immigration. He and his peers saw Canada as “a White man’s country,” and regarded any arrival by visible minorities to be the thin edge of the wedge and a disaster in the making.

Racism, Health, Deviance

As historian Esyllt Jones observes, the state and medical officials gave physical health an ethnic face. Crowded housing and poor water and sewage — widely recognized as causal factors when it came to infectious diseases — were disregarded when dealing with the immigrant, working poor, and non-White races. It was race and ethnicity (and social class) that Canadian authorities believed made newcomers sickly and, as well, a fertile ground for epidemics.[11] Local police authorities extended this way of thinking to social behaviour. Prostitution became associated with ethnic and visible minorities, particularly Chinese, Slavic, and Italian communities. Bootlegging — the production and sale of alcohol — is an example of an ancient rural practice that became criminalized in the early 20th century and used as an excuse to police the ethnic “other”. Organized gambling was another thread of moral corruption that was traced back to ethnic enclaves. Finally, the import and/or production and sale of restricted drugs — from opium to heroin — was transformed from a criminal practice into an ethnic and racial crisis. Described as morally, physically, and socially “diseased,” Canada’s ethnic and racial “others” were wrapped in a language that took on scientific and epidemiological tones. Once these notions were affixed to immigrant groups, the logic of barring them from medical schools and positions of responsibility became all but unassailable.

While it is true that official anti-Asian sentiment began to decline around 1947, prejudices remained. Anti-Semitic positions proved especially resilient, as did xenophobia regarding Muslims, Sikhs, Hindus, and members of other minority, non-Christian faiths. Twenty years ago, the distinguished Canadian historian Desmond Morton, wrote that pre-WWII Canada was “a poor country, full of people who were generous to those they knew, mean-spirited to those they didn’t, and harsh about the distinctions.”[12] This tension between a country that needed and wanted immigration but didn’t necessarily want immigrants took new forms in the years after the Great War.

Key Points

- Racism constituted a set of beliefs about racial hierarchies and policy alternatives.

- Some regions acquired greater diversity than others, including the largest cities and the Prairie West.

- These were the areas where acts of racial and ethnic discrimination were most widespread.

- Anti-African and anti-Asian racism was expressed in policies and practices aimed to reduce or at least limit the size of the communities in question.

- The only European community that faced comparable discrimination was the Jewish diaspora.

- Immigrant communities developed their own respective strategies to secure survival at least and prosperity at best.

Long Descriptions

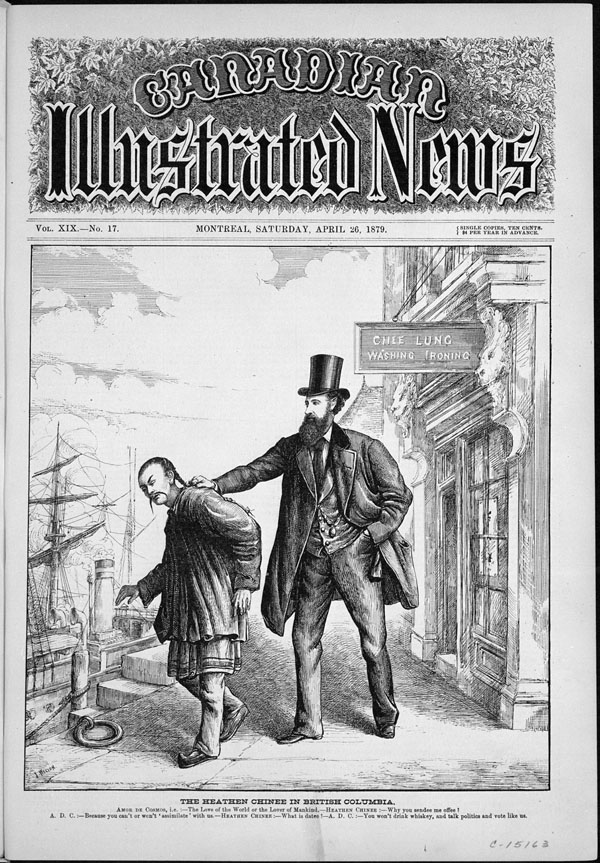

Figure 5.13 long description: Cover of the Canadian Illustrated News, Vol. XIX, No. 17. Published in Montreal on Saturday, April 26, 1879. The cover has a sketch of B.C. Premier Amor de Cosmos wearing an overcoat and top hat, one hand casually in his pocket, the other pushing a Chinese immigrant down the street. The Chinese man has his hair in a braid, a Fu Manchu moustache, and is wearing a tunic of sorts. The two men stand outside of a shop with the sign “Chee Lung Washing Ironing.” The shop appears to be on the waterfront, with ship masts in the background.

The caption says “The Heathen Chinee in British Columbia.” Amor De Cosmos says, “The Love of the World or the Lover of Mankind.” The “Heathen Chinee” says, “Why you sendee me offee?” A.D.C. says, “Because you can’t or won’t ‘assimilate’ with us.” The Heathen Chinee says “What is [that]?” A.D.C. says, “You won’t drink whiskey, and talk politics and vote like us.” [Return to Figure 5.13]

Media Attributions

- Powell River, British Columbia, 1944 © Harry Rowed, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3197254) is licensed under a Public Domain license

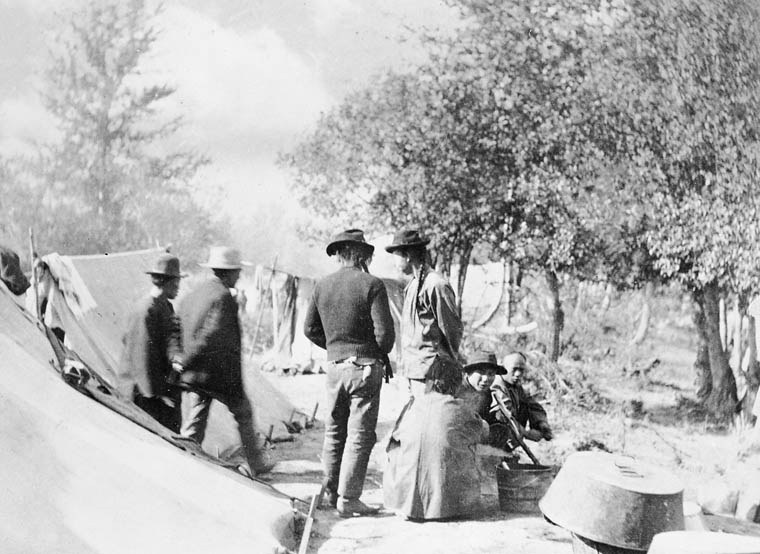

- Chinese camp (Canadian Pacific Railway), Kamloops, British Columbia, 1886 © Edouard Deville, Library and Archives Canada (C-021990) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- The Heathen Chinese In British Columbia, 1879 © J. Weston, Canadian Illustrated News, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 2914880) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Damage to property of Japanese residents, 1907 © William Lyon Mackenzie King, Library and Archives Canada (C-014118) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sikhs aboard Komagata Maru, 1914 © Leonard Juda Frank is licensed under a Public Domain license

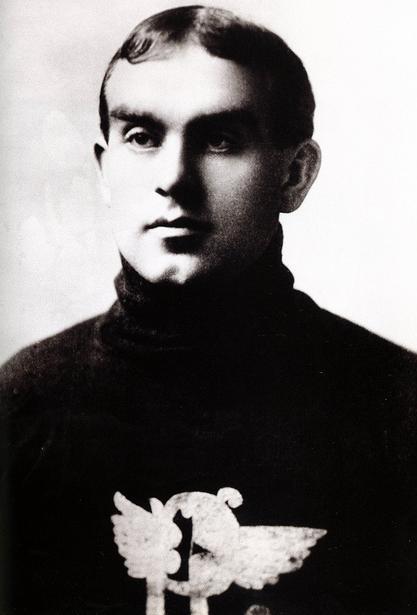

- Fred “Cyclone” Taylor, ca. 1906 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- John Zucchi, A History of Ethnic Enclaves in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 2007), 4-5. ↵

- Donald H. Avery, Reluctant Hosts: Canada’s Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896-1994 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995), 29-30. ↵

- Quoted in Jeremy Mouat, Roaring Days: Rossland’s Mines and the History of British Columbia (Vancouver: University of British C0lumbia Press, 1995), 96-7. ↵

- Quoted in Leslie A. Robertson, Imagining Difference: Legend, Curse, and Spectacle in a Canadian Mining Town (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005), 57. ↵

- James W. St. G. Walker, Racial Discrimination In Canada: The Black Experience (Ottawa: The Canadian Historical Association, Historical Booklet No. 41, 1985), 14-15. ↵

- Paul Yee, “Business Devices from Two Worlds: The Chinese in Early Vancouver,” BC Studies, 62 (Summer 1984): 44-67. ↵

- Quoted in Lisa Pasolli, Working Mothers and the Child Care Dilemma: A History of British Columbia's Social Policy (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2015), 30. ↵

- Still the definitive work on this question is Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 (Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1983). ↵

- Midge Ayukawa, "Good Wives and Wise Mothers: Japanese Picture Brides in Early Twentieth Century British Columbia," BC Studies, nos.105-106 (Spring/Summer 1995): 103-118. ↵

- See W. Peter Ward, White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Toward Orientals in British Columbia, 3rd ed. (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002) and Hugh J. M. Johnston, The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada's Colour Bar, revised ed. (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014). ↵

- Esyllt W. Jones, “Disease as Embodied Praxis: Epidemics, Public Health, and Working-Class Resistance in Winnipeg, 1906-19,” The West and Beyond: New Perspectives on an Imagined Region, eds. Alvin Finkel, Sarah Carter, Peter Fortna (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2010): 207-9. ↵

- Desmond Morton, 1945 - When Canada Won the War, Historical Booklet No. 54 (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1995), 3. ↵

A set of beliefs and practices that involve the creation of largely arbitrary categories of human peoples and assigning to them behaviours, traits, and tendencies that are essentialized — that is, thought to be an inherent and immutable part of who they are. For example, laziness, alcoholism, unbridled libido, personal restraint and self discipline, deceitfulness, superior or inferior intelligence, greed, corruptibility, cowardice, and courage have, at various times, been regarded as unchangeable qualities of one race or another. As an ideology, argues that the assumed existence of these differences justifies — and necessitates — the development of social policies that reduce the impact that might be had by the less desirable races.

A labour market in which employers have the option of hiring cheaper labour that is differentiated by race, ethnicity or, possibly, creed. Doing so improves profits and it will embitter relations between the two labour supplies. Used as a theory (split labour market theory) to explain racial divisions between workers.

A movement or individual committed to preserving privileges to established members of a community over newcomers; often translates into anti-immigration attitudes; many nativists are themselves merely earlier immigrants; has nothing to do with Native peoples.

In the United States, post-Civil War racial segregation laws that discriminated against African-Americans; most formal elements dissolved in the 1950s and ’60s in the Civil Rights Movement; was one cause of African-Americans emigrating to Canada in the Laurier and Borden eras.

Colloquial term for enclaves of Chinese immigrants. In Canada and primarily in British Columbia, these appeared from 1858 on, with the greatest increase occurring during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Created by external forces (Euro-Canadian civic authority limiting Chinese property ownership and business licenses to a small area) and internal needs (the concentration of Chinese financial and social institutions).

An organization that coordinated the interests and politics of the various community organizations in Chinatowns, and provided different levels of social support for its members.

Immigrants whose intent is to work for a period of time, accumulate savings, and return to their home country (or province). Historically associated mostly with Chinese labourers who were brought to Canada under contract to the Canadian Pacific Railway, for example.

A fee levied by the British Columbian and then the federal government on Chinese immigrants, beginning in 1885 and continuing to 1923.

Fear of China or Chinese.

1908; also known as the Lemieux-Hayashi Agreement; the Japanese government agreed to restrict the number of people leaving Japan for Canada. A loophole allowing wives to join their husbands led to significant use of the "picture bride" system thereafter.

Regulation passed by the federal government in 1908 to restrict immigration from India and Japan; required immigrants to reach Canada by means of a single, continuous, unbroken voyage. Would affect long journeys that necessitated a stop in either Japan or Hawaii. Tightened in 1914, leading to the challenge posed by the Komagata Maru.

Unlicensed, typically illegal production of alcohol. Also, in some instances, the sale of the same or of other illicit goods.