Chapter 8. The Economy since 1920

8.5 The Great Depression

The 1930s Depression is profoundly and deeply associated, in the popular mind, with the prairie Dust Bowl, one of the greatest environmental catastrophes in Canadian history. It was, in fact, something like a ticking time-bomb.

The British sent an expedition across the Prairies in the 1850s, led by John Palliser (1817-1887). Thereafter, his name was given to a tract of arid land along the 49th parallel. Palliser’s Triangle was identified as the northern tip of the Great American Desert, a region identified in the 1820s as stretching like a wall north from Texas and west from the 100th meridian to the Rocky Mountains. In 1874 a corps of 275 North-West Mounted Police, led by Commissioner George Arthur French (1841-1921), were dismayed to find Palliser’s Triangle so inhospitable. Sent to the West to begin the process of the Canadian occupation of Indigenous lands, French’s troops struggled to find drinkable water and, when they met up with Sioux soldiers, French “impressed upon them the fact that we did not want their land.”[1] He wasn’t lying. There was nothing about the region to suggest any farming potential to French and the Mounties. Thereafter, the plains and prairies entered into a wet period, the landscape turned a more promising shade of green, and its agricultural limitations were brushed aside by a Canadian government eager to populate the region with producers of food and consumers of manufactured goods.

Elsewhere on the prairies, and deep into the American plains as well, the prevalent form of agriculture in these years was dry land farming, which involves breaking the soil (with iron or steel ploughs) to a significant depth to release the moisture captured below ground. Once that moisture is used by the crops or evaporates, there is little to hold together the topsoil other than broken plant roots. After a generation or so under the plough, that part of the soil’s integrity vanishes as well. A drought — even a single year with little or no rain — could cause significant and widespread damage.

The “southern route” taken by the CPR ensured that Palliser’s Triangle was quickly surveyed and homesteaded. Improved grain prices in the 1920s led to more aggressive and widespread sod-busting across the prairies. When drought began in 1930 — an unfortunate coincidence with the Wall Street Crash — the reach of modern agriculture across the centre of North America had reached a new peak. Everything came to a head in the 1930s due to bad choices in the distribution of land, the heavy and sudden resettlement of the West, an over-aggressive and industrial approach to soil use, the elimination of trees as windbreaks (instead, trees were used as fuel and building material for homesteads), a booming economy in the 1920s, and the depletion of aquifers.

The Dirty Thirties

Palliser had recognized — more than 70 years earlier — that the southern Prairies were subject to drought conditions and these, as it turned out, were cyclical. The conditions in the early 1930s were ideal for dust storms. Prairie topsoil was picked up by the wind and blown from the southwest as far as Hudson’s Bay. Dust storms became increasingly common (and larger) as the Depression wore on. In 1935, one pan-continental storm turned the skies black for days and reduced visibility to a matter of feet. Dunes of dust obliterated whole farms, leaving the landscape unrecognizable. The influential 1941 Canadian novel As For Me and My House by Sinclair Ross describes “dust clouds lapping at the sky” and the constant intrusion of dust under the windowsills and doorsills, and into clothes, food, and the pores of exposed skin.[2] If this wasn’t enough, the West faced two other plagues: grasshoppers and hailstorms. More than a few contemporary writers have referred to these hardships as of biblical proportions.

A quarter million Canadian farmers — the greatest number from Saskatchewan — fled this catastrophe between 1931 and 1941 by heading for British Columbia (mostly) and Ontario. Those who remained behind received some support from a relief effort mustered by private citizens and government. The Dust Bowl changed the farming landscape of the prairies, and it would have a long-term impact on farming practices. It also created a new diaspora out of first- and second-generation Westerners who had left behind other homelands to become homesteaders and were now environmental refugees. As well, the Dust Bowl contributed significantly to the growth of distinctive political ideologies and attitudes that propelled reform movements on the right and left.

When the Wall Street stock market crashed in October 1929, a dogmatic position of non-interference in the economy was orthodoxy. It was embraced by Canada’s federal Liberal and Conservative parties alike. Given that the core electorate in these years was still decisively in Ontario and Quebec (where economic diversification dampened some of the worst impacts of the crisis) and the Maritimes (which, already in poor shape, didn’t experience the 1930s as a disaster of quite the same magnitude), the instinctive caution of federal politicians should have come as no surprise.

A Perfect Storm

Even by 1928, more than a year before the stock market disaster, there were signs of trouble. Commodity prices were wobbling and new house construction was slowing. Population growth was another issue. The inter-war years (1919-1938) began with substantial out-migration from war-torn Europe, which decreased almost as quickly. Immigration from China was effectively stopped by the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923. Growth in the population of Canada was coming from natural increase (births over deaths) more than immigration for the first time since the 1870s, despite the fact that the number of men of marriageable-age was reduced by the mortalities of 1914-1919.

Indebtedness was another factor leading to a fall. The arrival of new combine harvester technology in the 1920s meant that farm families borrowed to mechanize their output. As well, families were graduating from the sod-huts and simple wood frame cabins of homesteaders into larger and more expensive homes. In addition, automobiles were becoming more common, many of which were bought on credit.

There were external factors to consider as well. International currencies were in trouble, most spectacularly in the Weimar Republic (Germany). The system of mutual dependence produced by Germany’s obligation to pay reparations after the Great War meant that all countries had a significant stake in what was occurring in Weimar. In addition, most North Atlantic economies had returned to the gold standard (a commonly-pegged way of insuring the value of a nation’s currency), but at the pre-WWI rate, which significantly disadvantaged several currencies.

Another factor often overlooked is the inexperience of new stock markets. Until 1914, the City of London was the unquestioned financial capital of the world. As the interwar years began, there was growing competition for this title from financial hubs and stock exchanges in Paris, Tokyo, and New York, among other places. Decentralized control over the global investment economy pulled capital in different directions, increasing risks (and exposure to inexperienced brokers) while adding little to the building of a global fiscal safety net.

Thus, the stage was being set for a massive economic collapse by inflated currencies, the popularizing of gambling on the stock exchange, over-extension of household and industrial credit, heavy capital investment in machinery and buildings, a teetering international monetary and capital network, and a bubble in the commodities exchanges. When trade on the New York Stock Exchange crashed on Black Tuesday, 24 October 1929, the die was cast.

Living with Depression

In late 1929, no one could know for certain how long it would be before prosperity returned; few would have guessed that a whole decade of economic pain would pass before the economy could be urged back to life. The axiom that “generals are always ready to fight the last war” was, in fact, coined in the 1930s to describe the economic strategies that were wheeled out to deal with the crisis. Ill-equipped to tackle either the fiscal complexities of the Depression or the social catastrophe that it produced, governments in Canada (for the most part) shied away from interfering and hoped for the best.

The collapse of the international commodities market dramatically impacted the Canadian and Newfoundland economies. What, after all, was the commodities market but another term for the staple economy? Both Dominions had been producing unprocessed goods for trade abroad since the 16th century and, despite some progress in central Canadian manufacturing, they were doing much the same in the 20th century. Grain dominated, closely followed by wood products (lumber and paper) and minerals. These were precisely the commodities that bottomed out. The monoculture of Prairie farming was effectively vapourized by the Crash and the Dust Bowl. In British Columbia, the company towns and logging camps that relied on transient labour (much of it comprised of single males) were likewise hit hard. Migrant workers from the prairies and BC’s own seasonal workers followed a cycle of working across the West and then back to Vancouver to ride out the winters. The city’s oldest neighbourhood was carpeted with hotels, “flophouses,” brothels, vaudeville theatres, and saloons to take advantage of this traffic. The financial crisis occurred as the annual migration to the west coast hotels was underway, and when the 1930 work season arrived, vastly fewer jobs were available. As a “mecca to the unemployed,” Vancouver continued to attract large numbers of unemployed through the course of the Depression, with explosive results on several occasions.

Similar conditions prevailed on the East Coast. Unemployment and a stagnant economy was nothing new to the Atlantic region, but the old strategy of out-migration and seeking greener pastures was no longer available. The United States closed the door to Maritime immigrants, the Prairie West was wholly unattractive, and Canada established restrictions on immigration from Newfoundland. While seasonal work — as a way of making a living — survived in some regions, the appearance of full-time and continuous work in industry and in the office sector complicated matters. It was no longer just a matter of surviving until the next season of work came around; unemployment in the 1930s meant, for many people, the loss of full-time work. As unemployment climbed to 20% across the Atlantic region, in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, relief costs propelled one county after the next to consider bankruptcy.

The mechanization of farming across the Prairies had made possible massive increases in productivity while reducing the year-round value of family labour. Farm boys and farm girls were increasingly surplus to the family farm and, as they got older, they looked increasingly to urban or other rural pursuits. Some found work with threshing crews — teams of men and women who moved from farm to farm (at harvest time) along with the newest machinery for processing the wheat crop. These crews depended heavily on temporary workers who were hired and dismissed seasonally. Labour mobility was a critical part of the farm economy, and the cash income of threshing crew workers was important for the household economy as well. With the collapse in grain prices compounded by the Dust Bowl, seasonal work became immediately scarce, and impoverished by their inability to produce or sell grain, family farms found it a real burden to feed these temporary workers. The eldest sons in particular often were compelled to seek work elsewhere, to try to survive on their own, typically in cities and mines.

It is important to note that the impact of the Depression was felt well beyond the corridor of cities and farms in southern Canada. The 1920s had witnessed a boom in the fur-trade tied to the brief flicker of an international luxury market. This was good news for Native trappers and traders in the North, as was the arrival in 1901 of the Parisian Revillon Frères fur trading company; prices went up as Revillon went toe-to-toe with the local HBC traders. This situation, of course, invited growing competition from non-Native trappers and hunters, some of them by now long-residents in the region. The Innu of Labrador, for example, found themselves pushed further and further inland in the 1920s to eke out an existence that now was based almost entirely on the trade in furs. The possibility of fishing and hunting for food was by this point so reduced that they had no option but to adopt a European diet and Euro-Canadian clothing made available through the trade in furs.[3] The 1929 Wall Street Crash echoed even on the Labrador plateaus west of Nain and Kaipokok, and they would not be relieved — like the rest of the country — until the outbreak of the Second World War.

No Relief in Sight

As the Depression deepened, governments across Canada typically did very little. Conventional economic thinking called for a hands-off approach to economic downturns, and most provincial and federal administrations were very conventional in their thinking.

In retrospect, Mackenzie King was fortunate to have lost the election in 1930 because the worst years occurred under the Conservatives led by R.B. Bennett (see Section 6.7). The Conservatives arguably were inclined even more than the Liberals to allow the Depression to run its course, but they had no way of knowing how deep the troughs could get. Although by 1931 things were very bad, a slight hint of recovery arose in 1932 or, at least, things weren’t worsening as badly as in 1929-31. When 1933 came along, the Canadian economy plunged headlong into the deepest trade depression in its history. Unemployment reached 30%, and real GDP shrank by more than 10% in both 1931 and 1932. Some recovery would occur in 1934, but setbacks followed in 1935. Throughout these years, the federal government took a minimalist approach, holding onto its faith in a temporary readjustment and an unassisted return to prosperity. The electorate and the unemployed did not share that faith.

Thanks to the Depression, the 1930s would witness a dramatic politicization of the Canadian people. A variety of new partisan strategies would be explored at the ballot box, including the social democratic CCF (provincially and nationally), the monetarist Social Credit Party in Alberta, communist parties that could evade restrictions on their legal status, and even some fascist parties (see Sections 6.8 and 7.9). However, the issues of unemployment, dispossession, homelessness, and even hunger were so acute that they could not wait for election day. Unemployed workers, transients, and their supporters repeatedly took to the streets to register their bitter disappointment and to challenge authority.

Nowhere was this life of politics beyond the ballot box more visible than in Vancouver. Beginning in 1930, there were public demonstrations calling for action from civic, provincial, and federal levels of government. City charters limited what municipal authorities could do, and their tax base was drying up rapidly. Seizing homes in default of outstanding property taxes in a market like the 1930s only encumbered city governments. In the absence of anything like unemployment insurance, and with only a very limited welfare state in place, cities were the first stop for the unemployed looking for “relief.” This category of support could include anything from food (or chits for food), temporary housing, cash for necessities, clothing hand-outs, and/or work. Anglo-Canadian Protestant ethics made the case against relief as weakening recipients’ resolve to find employment, creating dependency, and as being demoralizing. Potential recipients likewise often found it shameful and degrading to accept, let alone ask for, relief. In language that spoke to heterosexual and patriarchal norms, people said it wasn’t manly. The sense that unemployment was the fault of the unemployed, however, began to dissipate in 1931 when it became clear that the Depression was the inevitable by-product of an international economic collapse. The result was that cities like Vancouver resisted giving relief, and the unemployed only asked for relief when they already were desperate. By 1931, many were desperate.

Social welfare is constitutionally a provincial responsibility. Provincial governments were hardly better off than the local authorities, and they were inclined to reinforce the message that it was first and foremost a local (that is, civic or municipal) matter. At the same time, they demanded that Ottawa address a problem that was clearly national in scope and made worse (in the case of many provinces) by the presence of migrant and out-of-province workers looking for relief or dole.

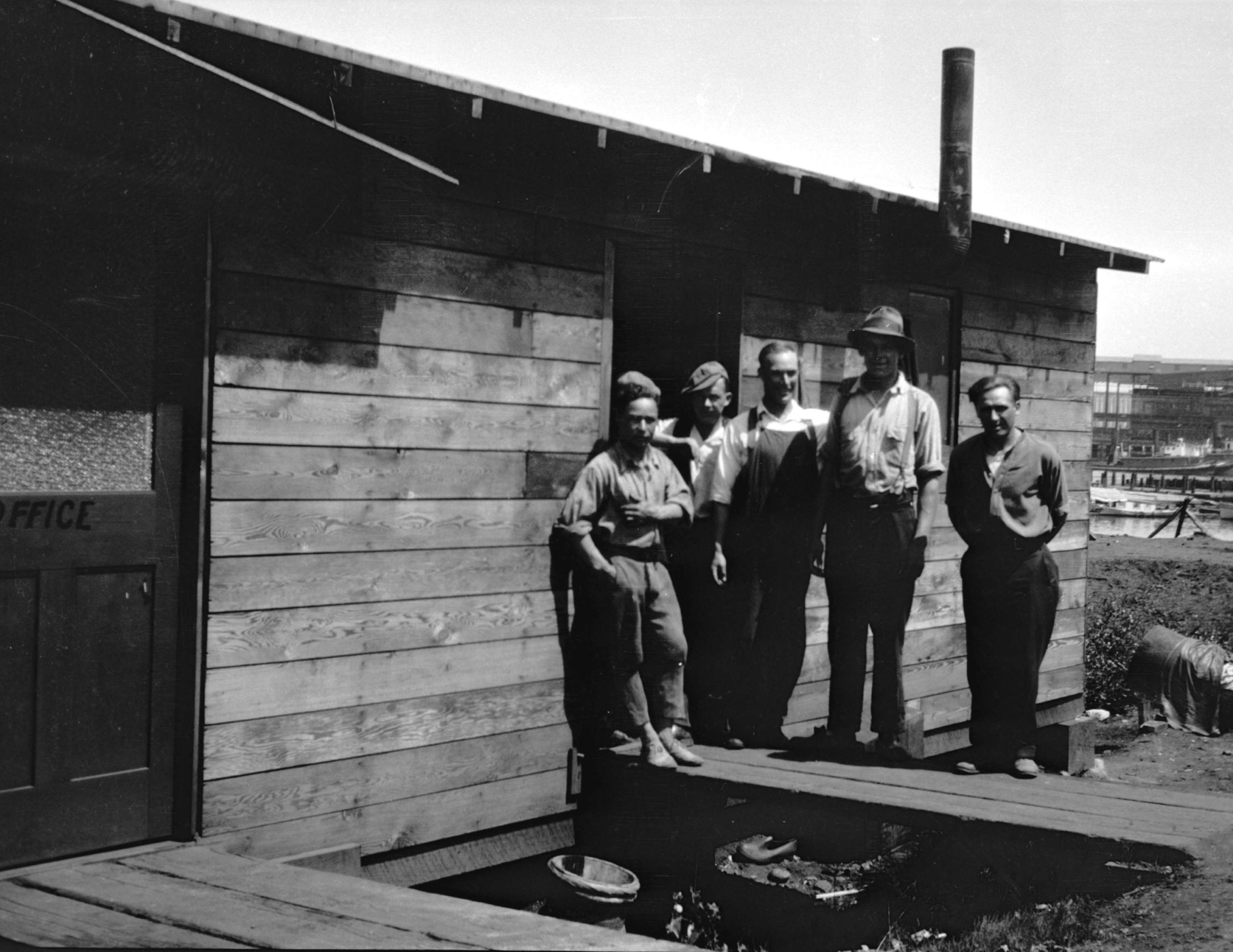

Conflict erupted in 1931, and again in 1933, in public demonstrations and around homeless men’s camps also called hobo jungles. Vancouver was especially attractive to the unemployed because it was at the end of the rail line, and the winter weather was relatively mild and tolerable. Communist activists and evangelicals campaigned in the hobo jungles. Both treated the unemployed community as a powder keg. The City of Vancouver (and other urban governments) responded by evacuating the jungles and relocating their residents to federally-built and Department of National Defence-run Relief Camps outside of the city limits, sometimes in remote parts of BC. Others were established in the national parks of the Rocky Mountains. The campgrounds and other holidaying facilities that post-WWII touring families would come to associate with the National Parks, were mostly created by unemployed workers in relief camps. For the most part, however, the unemployed in the relief camps performed meaningless routine work, colloquially referred to as “boondoggles.”[4] The unemployed worked for 20 cents a day (hence the nickname of the camps as the “Royal 20 Centers”) and under military-style discipline, which bought the city a little time that ran out quickly.

By 1933 conditions had worsened to such a point that the resident unemployed were clamouring for relief. What the City could offer in terms of projects or payments was by this stage very limited. Police surveillance of the unemployed was met with street fights and the occupation of public buildings and department stores. In 1933 the communists organized the Relief Camp Workers’ Union, which mobilized the extremely alienated unemployed across the region to abandon the camps and put their issues directly before Prime Minister Bennett. The On-to-Ottawa Trek set off from Vancouver on 3 June 1935 but was stopped in Regina, the site of the RCMP headquarters. Trek leaders headed on to Ottawa to meet with Bennett, but the discussion was cut short and quickly degenerated into name-calling. Once the leaders were back in Regina, a rally was called for the 1st of July — Dominion Day — in Regina’s Market Square. The Mounties’ riot squad surged into the crowd of 1500-2000 people (most of them local residents) with truncheons swinging. The Trek leadership was arrested, one constable and one protester died, and the campaign was broken.

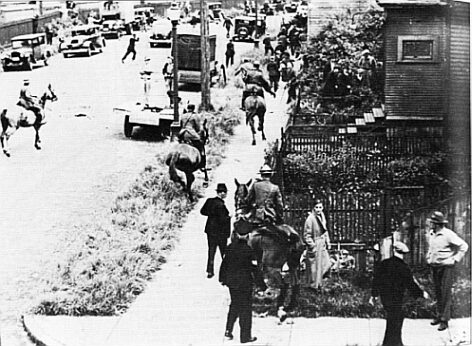

On the face of it, the Regina Riot seems extraordinary, but in the context of the Dirty Thirties, it was not. Conditions that led to the Battle of Ballantyne Pier were unfolding even as the Trekkers left Vancouver. Local dockyard workers had gone on strike and were replaced with strikebreakers brought in by the Shipping Federation (an organization of waterfront employers). Fifteen days after the Trekkers left Vancouver, the strikers marched to the waterfront, led by a Great War veteran and decorated hero. Confronted by mounted and armed City police, BC Provincial Police, and Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the march rapidly turned into a melee. Fighting continued for three hours across the East End, culminating in 24 arrests, about the same number hospitalized, and untold numbers injured.

New Dealers

Another casualty of these events was R. B. Bennett. His counterpart in the United States, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), launched a “New Deal” program shortly after his election in 1933, aimed at stimulating the economy through spending. This was heresy, in the context of conservative economic thinking, but it was attractive to legislators and civil servants because it put them in a position to act rather than defend inaction. Even Bennett seemed changed by this example. Beginning in January 1935, he endorsed economic intervention by the federal government. He introduced the Bank of Canada and the Canadian Wheat Board, but did not pursue economic pump-priming or efforts to spend his way out of the crisis. The electorate, worn out by conflict, hardship, and lack of government solutions; shocked at the violence inflicted on Canadians by Canadians; and convinced that the wealthy and snobbish Bennett was flinty-hearted tossed out the Conservatives in October 1935 and returned Mackenzie King’s Liberals.

Despite the rhetoric suggesting a greater sympathy for the unemployed, King turned out to be no more an interventionist than Bennett. King’s Liberal counterpart in BC, Thomas Dufferin “Duff” Pattullo, however, launched his own “Little New Deal” that, warts and all, demonstrated Keynesian thinking was gaining traction in some parts of Canada. King’s response was to reintroduce the hated relief camps, albeit with some slight improvements and significantly more isolation than before. These initiatives were not enough to still significant urban unrest. On 20 May, 1938, unemployed protesters occupied the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Hotel Georgia, and the main Post Office on Hastings Street at Granville. A month later, on Sunday, 19 June at daybreak, the Vancouver Police oversaw the largely peaceful evacuation of the Art Gallery; and at the same moment, the RCMP stormed the Post Office with teargas and truncheons. A window-smashing campaign followed and, hours later, a demonstration of support took place at an East End park where 10,000 to 15,000 locals gathered.

The Regina Riot and Bloody Sunday were merely the worst episodes in a long decade of street battles between various police forces and the unemployed. The war that terminated the economic Depression would force a reconsideration of economic orthodoxy in a way that the financial crisis had not, and the events of 1929-1939 would shape more than a generation of Canadian political culture. The sustained popularity of the CCF and Social Credit, mistrust of Ottawa and civic police forces, and a widespread tolerance for state intervention in the economy were only a few of the ways in which this one decade would transform Canada.

Key Points

- The 1930s Depression consisted of several events, including the Dust Bowl and the collapse of the commodities market.

- Economic and environmental disaster produced an out-migration from the Prairies, particularly from Saskatchewan.

- Seasonality in employment was deeply impacted with bad results for tens, if not hundreds of thousands of itinerant and semi-itinerant Canadian workers.

- The downturn profoundly affected all parts of Canada, some more deeply than others.

- Successive Conservative and Liberal governments developed few plans to directly reform the economy or introduce social welfare measures like employment insurance.

- The massification of unemployment and the concentration of the jobless in cities like Vancouver created conditions that led to violent street battle confrontations with police forces.

Media Attributions

- A dust storm over the prairies © Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan (S-A295) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Combined Harvester-Thresher operated by tractor © Library and Archives Canada (PA-040497) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bennett buggy, Alberta, 1936 © Glenbow Archives (NA-3958-3) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Strikers from unemployment relief camps en route to Eastern Canada during “March on Ottawa” © Library and Archives Canada (C-029399) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Battle of Ballantyne, 1935 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Citizens protest police terror is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Quoted in David C. Jones, Empire of Dust: Settling and Abandoning the Prairie Dry Belt (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1987), 8. ↵

- Sinclair Ross, As For Me and My House (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1941), 26. ↵

- Lynne D. Fitzhugh, The Labradorians: Voices from the Land of Cain (St. John’s: Breakwater, 1999), 375. ↵

- Bill Waiser, Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada's National Parks, 1915-1946 (Saskatoon: Fifth House, 1995). ↵

Describes the drought conditions that occurred across the prairies and plains of North America in the 1930s and the concurrent poverty associated with the economic depression.

At the end of the First World War, Germany accepted responsibility for acts of aggression leading to the conflict; the Treaty of Versailles (1919) ordered Germany to make extensive payments as a consequence. Both the idea of war guilt and reparations became a contentious issue in Germany; the country’s inability to pay the enormous reparations fees led to severe international economic instability, particularly when Germany sharply devalued its own currency to pay the debts more easily.

24 October 1929 (a Tuesday) was the day the New York Stock Exchange crashed, beginning the decade-long Great Depression.

The staples theory argues that an economy dominated by valuable and traditional commodities will be shaped — in terms of the larger economy, the polity, and the society — by the needs and nature of the primary staple(s). Also a model for understanding the political economy of a country in which staples are fundamental to the export economy. An approach developed by historians Harold Innis and W. A. Mackintosh.

Colloquial term for “relief” or welfare payments.

Homeless men’s camps, usually in marginal spaces in cities and towns, proliferated during the 1930s Depression.

The federal government‘s response to the massing of unemployed single men in Vancouver early in the 1930s Depression; in 1932, a nationwide system of generally quite isolated camps run by the Department of National Defense that became hotbeds of radical opposition to government inaction on the economic crisis.

1st of July 1935, at the conclusion of the On-to-Ottawa Trek, a rally called by the Relief Camp Workers’ Union in Regina’s Market Square culminated in a confrontation between the Trekkers and their supporters and the RCMP.

18 June 1935; a violent confrontation between striking Vancouver dockyard workers and a force made up of city police, provincial police, and RCMP.

Canada’s central bank, introduced by R. B. Bennett, January 1935, as part of a federal government economic intervention.

Canada’s Marketing Board for wheat and barley was introduced by R. B. Bennett in July 1935 as part of a federal government economic intervention.

Named for the British economist, John Maynard Keynes, it broke with orthodox thinking by advocating government spending during downturns so as to stimulate the economy; these principles also encouraged aggressive taxation during times of prosperity to offset recovery-era spending. Resisted and rejected by orthodox economic thinkers and conservatives who deplore the idea of a large, bureaucratic, and interventionist state.

Sunday at daybreak, 19 June 1938, while the Vancouver Police peacefully evacuated the Art Gallery (occupied by unemployed protesters); the RCMP stormed the Post Office with tear gas and truncheons. A window-smashing campaign followed and, hours later, a demonstration of support took place at an East End park where 10-15,000 locals gathered. Many were hospitalized that day.