Chapter 9. Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

9.3 The North: Economy and Territory

Kelly Black; Department of History; and Vancouver Island University

In Canadian history, the concept of the North — What is it? Where is it? What does it mean? — has been a contested and debated subject. At various times during Canada’s past, the geographic location of the North shifted as Canada acquired, surveyed, and mapped new territory. If we ask, “Where is the North?” we may think of the provincial north (Fort St. John, British Columbia; Timmins, Ontario; northern Quebec; Labrador), the territorial north (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), or any land north of the 60th parallel.

Whichever location comes to mind, all are home to a diversity of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples have made these places their home since time immemorial, and each of these peoples has specific territories and traditions. The North has also been central to the creation of particular narratives of Canadian identity. Historian Shelagh Grant has written that most southern Canadians “view the Arctic in terms of southern impact, such as the effect of weather patterns, the potential of untapped resource wealth, or simply national pride in a unique, majestic landscape.”[1] Just as the North moulds the nation, the nation fashions the North. The history of the North in Canada has been shaped by changing boundaries, changing priorities, and the development of a national, northward-looking imagination.

Canada First

The creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867 caused some English Canadians to consider what attributes would define their new identity as Canadians. A group called Canada First was formed in 1868 when five men from Ontario gathered to consider a future as Canadians, and not as British colonists. Historian Carl Berger argued that the Canada First movement used notions of the North to promote the idea that Canadians would rise to greatness in North America and abroad because of their northern character:

The adjective “northern” came to symbolize energy, strength, self-reliance, health, and purity, and its opposite, “southern,” was equated with decay and effeminacy, even libertinism, and disease. A lengthy catalogue of desirable national attributes resulting from the climate was compiled. No other weather was so conducive to maintaining health and stimulating robustness.[2]

The idea that Canadians were hardy, masculine, and northern people stood in contrast with the United States to the south. However, Canada First members also wanted to contrast Canadians with peoples from other colonies within the British Empire. The idea that people from southern climates could not live in the North was taken directly from the concepts of Social Darwinism emerging at the time. It was used to underwrite a cool welcome to (or a door bolted against) immigration from the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and the African-American diaspora. Social Darwinism took Darwin’s theory of evolution — survival of the fittest and natural selection — and applied these ideas to society and politics. Canada First’s doctrine argued that a northern climate meant only hardy, manly, and white peoples could live in Canada. This conveniently ignored the presence of Indigenous peoples but, to most Canadians at the time, Indigenous peoples were understood to be vanishing. With this “icy white nationalism,” as Eva Mackey has put it, whiteness, the rugged northern landscape, and climate came to signify Canada to Canadians.[3]

Territorial Expansion

The British government purchased “Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory” from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 1870. Fearing annexation of the territory by the United States, Section 146 of the British North America Act (1867) provided for the inclusion of the vast area into the newly created Dominion of Canada. This acquisition brought an influx of settlers, particularly from Ontario, into the Red River area, and led to the Red River Resistance by the Métis and the creation of the “postage stamp” province of Manitoba in 1871. It was not until 1905 that the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were carved out of the territory and brought into Confederation. In 1912, the current borders of the prairie provinces and northern Ontario were established.

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the far North, the lands North of 60, remained largely unknown to southern Canadians. It was not until 1880 that Britain transferred possession of the high Arctic islands to Canada. However, these islands were seen to be of little value to political leaders in Ottawa. Rather than being viewed as the home of the Inuit, the Arctic was mired in myth as the site of ill-fated expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage and thought to be a place of inhospitable climate; harsh landscape; and monstrous creatures such as whales, narwhals, and walruses.

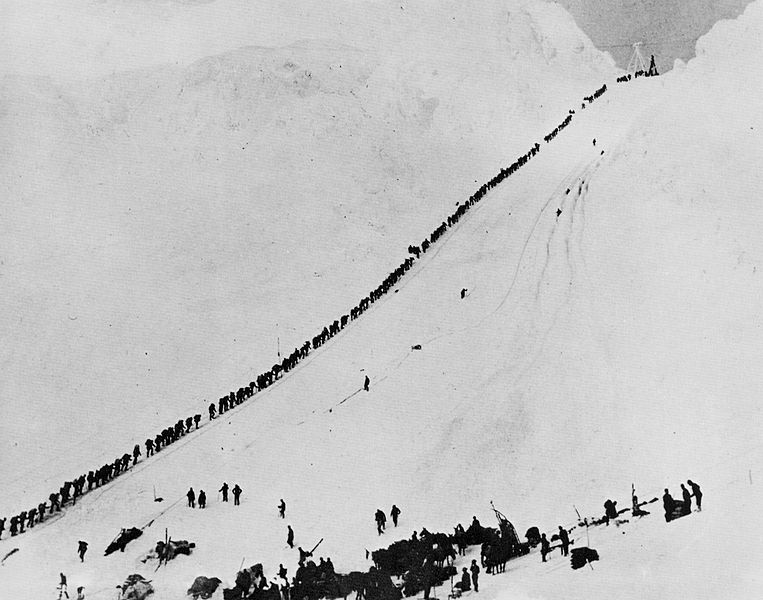

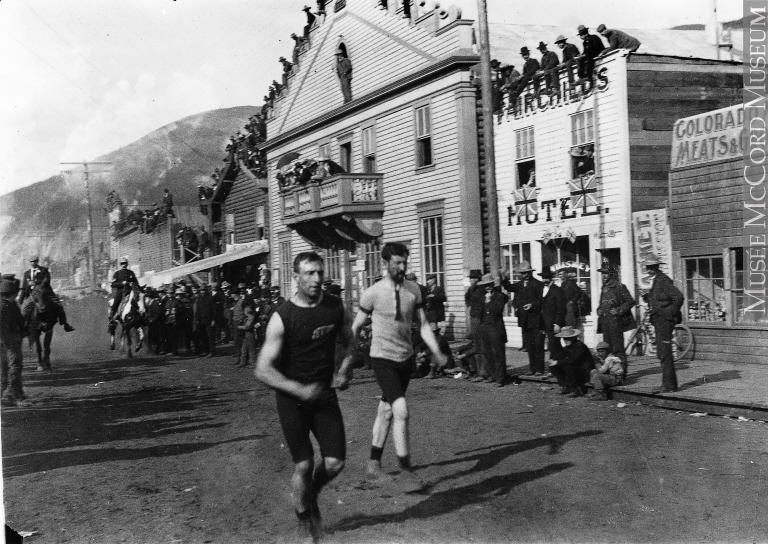

The Klondike gold rush of 1896 brought an influx of gold seekers to the North (especially from the United States), and the Canadian government responded by creating the Yukon Territory in 1898. Historians Ken S. Coates and William R. Morrison note that the Klondike gold rush “is one of the few events in Canadian history — perhaps the only one — that has entered into the collective memory of the entire world.”[4] The word Klondike is derived from Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, the name of the First Nation upon whose territory gold was found. The rush to riches had devastating impacts on the environment and First Nations cultures in the region, but it is the romance of the gold rush that remains ingrained in the Canadian imagination through the poems of Robert W. Service (1874-1958) , the books of popular historian Pierre Berton (1920-2004), and the famous images of stampeders climbing the treacherous Chilkoot Pass route to the goldfields.

Listen to this recording of The Cremation of Sam McGee. Service reads one of his best known poems, The Cremation of Sam McGee.

The gold rush reminded the Canadian government of the need to assert its sovereignty in the North, and, in 1904, the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier (1841-1919) commissioned the Canadian Arctic Expedition and the ship Arctic to help with this task. From 1913 to 1918, the Canadian Arctic Expedition journeyed through the Arctic and found major errors in previous maps. The expedition actually added four new islands to Canada’s territory that were previously unknown by the government. During this time, missionaries and the Royal North West/Canadian Mounted Police established outposts throughout the provincial and territorial North. These outposts, along with the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) stores, became central to the region’s colonization and administration prior to World War II.

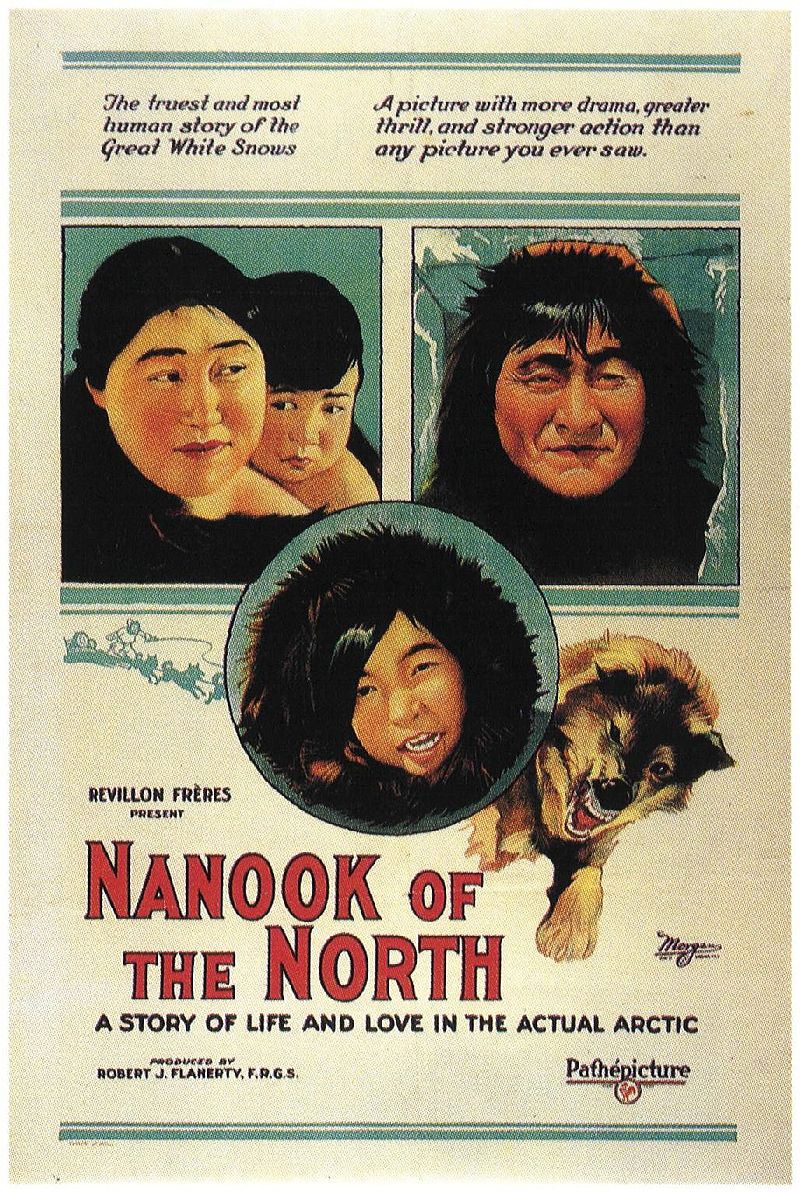

Despite the acquisition of Rupert’s Land by Canada, the HBC remained a strong presence in the North well into the 20th century. In 1920, the company marked its 250th anniversary with the release of the silent film The Romance of the Far Fur Country. The film reinforced the prominent role of the HBC in Canada and provided southern audiences with one of their earliest glimpses into life in the Arctic. Two years later, the American film Nanook of the North (nanook means “polar bear” in the Inuktitut language) was a huge success at the box office and contributed further to the mystique of the North and its peoples.

Watch Nanook of the North, a remarkable (if ethnographically unreliable) documentary.

World War II and the Cold War

World War II brought rapid and profound change to the North and to Indigenous peoples in the region. When the United States and Canada declared war with Japan in December 1941, the Pacific coast of North America was particularly vulnerable to a Japanese attack. To aid the movement of troops and supplies into the North, work began on the Alaska Highway in Fort Nelson, BC, in 1942. With Canada’s permission, 10,000 American troops and workers came to northern British Columbia and the Yukon to build a 1500-mile (2400-kilometre) road to Alaska. As with the gold rush, the North was transformed almost overnight. American troops remained in the North not only to build the highway but also to facilitate defence and the transportation of military supplies across the North.

Prior to the war, it was possible for many Indigenous peoples in the North to live their lives without interacting with Canadian institutions and peoples. However, concerns about sovereignty and security quickly brought scientific and military projects into the everyday lives of Indigenous peoples. A mine near Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories supplied uranium ore for the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bomb. The Délįne First Nation of Sahtu worked to extract the radioactive materials and were never informed by the government of uranium’s deadly effects: many died from various forms of cancer linked to their exposure.[5] Advancements in technology following the war meant that the Arctic very quickly went from a place of mystery to a place that could be accessed, studied, defended, and monitored. During the 1950s, the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line was built across the North to provide radar surveillance and protection from a Soviet airborne invasion or missile attack via the Arctic Circle. Although such an invasion never came, the United States military maintained a strong presence in the North throughout the Cold War.

High Arctic Relocation

As southern Canadians came to know more about the North, the federal government extended the postwar welfare state to Northern peoples. This was not simply an offer of social programs; the federal government wanted to resettle Indigenous peoples off the land and into planned settlements in an attempt to reproduce life as it was for southern Canadians. This rapid transformation in people’s lives often meant disruption of traditional ways of knowing and the break-up of family groups. The need for energy and other resources in the postwar years also brought resource extraction to the North. In the quest for resources, traditional hunting grounds were destroyed and settlements were relocated to make way for mining operations.

In the late summer of 1953, the government forcibly relocated several Inuit families from Inukjuak, Quebec, in the name of Canadian arctic sovereignty. The families, along with a single RCMP constable, were sent to Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord in the Northwest Territories as part of a government relocation program. Three other families from Pond Inlet were sent to teach the Inukjuak families to survive in the high Arctic. All of these families were told they were being sent north so that they could be provided better hunting and living opportunities. In 1955, more people were relocated from Inukjuak and Pond Inlet to Resolute. The high Arctic was completely different than the home territories of these families, and they were sent North with poor supplies and no knowledge of the terrain or wildlife. In 1996, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples found that the government relocated these Inuit families for several dubious reasons:

- To support Canadian sovereignty claims (in effect, using the relocated populations as “human flagpoles”);[6]

- To centralize Inuit in communities where they could provide labour for the Royal Canadian Air Force and government weather station. Many Inuit did these jobs but were not paid. Their wages were kept by the government and issued in the form of credits at the government store;

- To fulfill a desire to improve the situation of Quebec Inuit whose livelihoods were thought to be under threat due to decreased game stocks; and,

- To reduce what was seen to be growing Indigenous dependence on government assistance.

For decades, the federal government claimed that these families had moved voluntarily. Inuit rejected this claim and spoke of the intergenerational trauma inflicted by forced relocations. It was not until 2010 that the federal government issued an apology for these relocation programs.

Division of the Northwest Territories

Since 1867, the size and shape of the NT has been altered several times as districts, provinces, and territories were created. Prior to the 1960s, the administration and governance of both the Yukon and Northwest Territories was the responsibility of the federal government. In 1966, the Carruthers Commission recommended that the federal government begin to transfer these responsibilities to the people of the Northwest Territories. Following the commission’s report, the capital of the Northwest Territories was shifted from Ottawa to Yellowknife in 1967 and, by 1975, a fully elected legislative assembly had been created. Gradually, control of education, local government, and social services were handed over to both territories, a process known as devolution.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Indigenous peoples of the North began to organize politically into groups such as the Yukon Native Brotherhood, the Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories, the Committee for Original Peoples Entitlement, and the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada. These groups advocated for the protection of their culture and traditions and called for the signing of treaties and the right to determine their own future. As a creation of Ottawa, the boundaries of the Northwest Territories were artificial and did not represent the cultural and linguistic differences between Inuit and First Nations in the Eastern and Western Arctic. Inuit made up the majority of the population in the East, while Dene and Métis concentrated heavily in the West, around Great Slave Lake and the Mackenzie River.[7] In 1982, residents voted in a plebiscite that asked if they were in favour or against a division of the Northwest Territories. Nearly 57% of voters cast a ballot in favour of the proposal. Ten years later, in 1992, residents voted on and approved the proposed boundaries for the two territories. In 1993, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was signed between Inuit of the Eastern Arctic and the federal government. The finalization of the land claim agreement was one of the last major hurdles towards the creation of Nunavut, which became Canada’s newest territory on 1 April 1999.

Key Points

- The North has played an important role in the psychology of national identity since the earliest days of Confederation.

- In the early 20th century, much northern territory was divided between the Prairie provinces, Ontario, and Quebec.

- Efforts to assert Canadian sovereignty in the North were insignificant before the Klondike gold rush and increased thereafter.

- Government involvement grew and extended dramatically during World War II.

- Mineral resources began being tapped in the Northwest Territories precisely as the Cold War began, adding new concerns about sovereignty and a degree of militarization in response.

- Human populations — mostly Inuit — have been repeatedly moved in the service of Canadian claims.

- Democratic institutions were introduced in the 1960s and 1970s while, at the same time, Indigenous peoples organized in response to Ottawa’s interest in their homeland.

- One outcome was the establishment of Nunavut as a separate territory in keeping with Inuit ambitions.

Additional Resources

CBC Digital Archives. The Creation of Nunavut

Mapping the Way: Yukon First Nation Self-Government

CBC Interactive Timeline: NWT Devolution

Long Descriptions

Figure 9.13 long description: A 1922 movie poster for Nanook of the North: A story of life and love in the actual Arctic. There are images of an Inuit woman and child, an Inuit man wearing a parka, an Inuit child wearing a parka, and a wolf, baring its teeth and leaping. The text at the top of the poster says “The truest and most human story of the Great White Snows” and “A picture with more drama, greater thrill, and stronger action than any picture you ever saw.” The film is presented by Revillon Frères and produced by Robert J. Flaherty, F.R.G.S. [Return to Figure 9.13]

Media Attributions

- 60th parallel in Canada © Wikipedia user Bazonka is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Packers ascending summit of Chilkoot Pass, c.1899 © E.A. Hegg, Library and Archives Canada (C-005142) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Foot race, Dawson City, YT, about 1900 © McCord Museum (MP-0000.2360.36) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Nanook of the North (1922) © Robert J. Flannery / Pathe Pictures is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Shelagh Grant, “Arctic Wilderness - And Other Mythologies,” Journal of Canadian Studies 32.2 (1998): 35. ↵

- Carl Berger, The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, 1867 - 1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 129. ↵

- Eva Mackey, ““Death by Landscape”: Race, Nature, and Gender in Canadian Nationalist Mythology," Canadian Woman Studies 20.2 (2000): 126. ↵

- Ken S. Coates and William R. Morrison, Land of the Midnight Sun: A History of the Yukon (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), 77. ↵

- Peter C. van Wyck, The Highway of the Atom (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010). ↵

- Bruce Campion-Smith, “Ottawa apologizes to Inuit for using them as ‘human flagpoles,’” Toronto Star, August 18, 2010. ↵

- Frances Abele and Mark O. Dickerson, “The 1982 Plebiscite on Division of the Northwest Territories: Regional Government and Federal Policy,” Canadian Public Policy/Analyse De Politiques 11.1 (1985): 2. ↵

The locus of the 1890s gold rush in the Yukon Territory, along the Klondike River valley; used to describe the gold rush as a whole.

A highway built during WWII to facilitate the movement of troops and materiel from the United States to its northern territory (not yet a state), Alaska. It was constructed between Dawson Creek, BC, and Delta Junction, Alaska, and completed in 1942. It served to open the Yukon to greater traffic and activity.

The northernmost of three Cold War radar systems aligned from west to east to identify incoming Soviet missiles in the event of an attack.

A federal government initiative in the mid-20th century to move Indigenous peoples in the North to locations where they would serve as a sign of Canadian sovereignty and/or where services (education, healthcare, administration, and the church) might be more effectively centralized. A program to which Inuit in particular were subjected, their lives disrupted, and their economies severed.

Established in 1963 and reported out in 1966; recommended a devolution of authority from Ottawa to the North West Territories; headquartered at Yellowknife.

This when a senior level of government hands some of its authority to a lower level or ostensibly lower level of administration. In Canada in the 1960s, authority over the North-West Territories devolved to the new administration in Yellowknife, NWT.

1993; set the stage for the Nunavut Act, 1999 that created the new territory of Nunavut; the first major land claims agreement negotiated by the federal government since Treaty 11 (1920 to 1921).