Chapter 9. Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

9.9 Cold War Quebec

The mid-20th century produced several provincial leaders who would cast a long shadow over their provinces in an age of growing government involvement in economic, infrastructural, educational, and social policy. This has been called an era of province building. Its chief practitioners — Ernest Manning in Alberta; Tommy Douglas in Saskatchewan; Joey Smallwood in Newfoundland; W.A.C. Bennett in British Columbia; Richard Hatfield in New Brunswick; and a trio of Conservative Premiers (Leslie Frost, John Robarts, and Bill Davis) who governed Ontario from 1949 to 1985 — were each in office for at least a decade, and for as much as 22 and a half years. Each of them had the time to map out and execute significant changes in their respective jurisdictions. Such longevity in politics was rare before World War II; it has been rarer since 1990. They were, clearly, a generation of leaders who had the good fortune to be in office in rising economic times. In Quebec, the political beneficiary of these circumstances was Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis (1890-1959), an exceptional personality in Canadian politics.

Pre-WWII Leadership in Quebec

The first half of the 20th century saw remarkable continuity in Quebec’s political leadership. Between them, only four men held the position of premier from 1905 to 1959. Lomer Gouin (1861-1929) became premier in 1905 after a bitter struggle between factions in the Liberal Party in Quebec. Divided between moderate and radical wings, the Liberals were torn on issues like support for modernizing industrial corporations and rapprochement with the Catholic Church on the one hand, versus state control over education and a more aggressively pro-labour policy on the other. Gouin stood out as a compromiser who had Wilfrid Laurier’s support. He spent 15 years extending Quebec’s northern borders, enticing new industrial enterprises to invest in the province, and advancing the nationalist agenda by developing technical schools and programs that would enable more Quebecers to take advantage of the emergent modern economy. Gouin also calmed the clergy by promising to keep the state out of education and even enhancing Church control over technical education. Nationalistes and labour complained that Gouin was too keen to attract foreign investment and foreign-owned plants that siphoned off profits to other countries and consigned Quebecers to low paying industrial jobs. Just as the West was crafted as an Anglo-Canadian settlement frontier, the growing French-Canadian population was inclined to look to colonization opportunities within the newly expanded Quebec. This was not, however, part of Gouin’s vision. His Conservative and nationaliste opponents alike attacked him for trading off Quebec lands for timber and mining purposes rather than making those properties available for Québecois resettlement and colonization. Gouin’s political instincts were, otherwise, outstandingly shrewd. He supported Laurier in 1911 but swung to Borden’s side at the outbreak of war. As conscription became a sharper issue, Gouin abandoned Borden and joined the chorus of nationalist voices in Quebec, criticizing Ontario’s Regulation 17 and Anglo-Canadian Francophobia generally (see Sections 6.3 and 6.4). By 1919, Gouin was demonstrably an ideological conservative — a defender of Quebec’s rights in Confederation, while simultaneously a Canadian nationalist. He commanded respect in Quebec City and in the corridors of power in Ottawa.[1]

Gouin’s resignation in 1920 placed the Liberal Party and the provincial administration in the hands of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau (1867-1952). Like Gouin, Taschereau would hold the reins of power for 16 years. Biographies of Taschereau describe him as more pro-industry and pro-business than his predecessor, as well as less likely to defer to the Catholic clergy on education matters. This is true, but it is certainly the case that Taschereau inherited a more industrialized and modernized society than the one first governed by Gouin. In other words, it may be said that he was simply continuing the arc of earlier developments. And he was faced with long-term Québecois concerns. Emigration from Quebec — understood as a depopulation that sapped the strength of the French nation in Canada — had been underway since the mid-19th century. In the 1920s and, even more decisively, the 1930s, this exodus was renewed as young Québecois people searched for work elsewhere and principally in the New England states. Efforts on the part of the National Assembly to slow, halt, and even reverse that trend were applauded by all flavours of French-Canadian politics and society. To that end, Taschereau was noteworthy for developing some of the first major hydroelectric projects in Quebec, massive employers that offered a foretaste of the economic nationalism of the post-1960 provincial economy. These and other initiatives favoured urbanization over agrarian Quebec, the secularization of education (including an attempt to bring Quebec’s large Jewish community into the educational decision-making process), and adding cosmopolitan aspects to cultural life in an otherwise very provincial province. These more controversial projects ran up against nationalistes, clergy, Conservatives, and radical Liberals alike, particularly as the 1930s Depression deepened. Elements of the left-wing of the Liberal Party split off to form Action libérale nationale (ALN), a new political party led by Gouin’s son, Paul, which brought together nationaliste, socially progressive, and rural groups. Taschereau was in trouble, but he is almost unique in Canada in that he was elected before the Depression and yet was re-elected — twice — in 1931 and 1935. A corruption scandal forced him from office in 1936, and the Liberal Party leadership was handed to Adélard Godbout (1892-1956). Quebec returned to the polls in the summer of the same year and the Liberals lost decisively.

The 1936 election was a landmark. In 1935, the opposition vote had been split between the Conservatives (with 19% of the ballots cast) and the ALN (29.4%). Although Godbout’s Liberals saw their support shrink in 1936 from 46% to 39%, that would have been enough to defeat their opponents had they remained unaligned. The frustrated Conservatives and ALN, however, had come to an agreement, forming the Union Nationale (UN) coalition under the leadership of Duplessis. Gouin distanced himself from Duplessis even before the 1936 election and unsuccessfully attempted to resurrect the ALN from 1938 to 1939. What emerged was essentially a transformed Conservative Party — an ideologically conservative UN with a broad base of rural, economically regressive, pro-Church, and nationalistic voters. The UN turned its back on the Taschereau era’s support for hydroelectric projects, a move that condemned rural Quebec to another generation of wood stoves, gas and kerosene lighting, iceboxes, and no radios or telephones. This anti-technological bent would persist in some form for nearly two decades.

Duplessis’ victory was initially a short-lived one. In 1939, as Canada stood on the brink of war, the spectre of conscription returned to Quebec. Federal Liberals from Quebec promised to block attempts to reintroduce conscription, a commitment that served provincial Liberals well. Godbout was swept back to power with 70 of 86 seats, and the UN was reduced to a 15-seat rump. The Liberal wartime government introduced a slate of landmark legislation, including the provincial franchise for women (thereby bringing Quebec into line with all other provinces), reforms to education to make it simultaneously more accessible and mandatory, and the introduction of Quebec’s first Labour Code. The first steps necessary to creating a provincially owned electricity monopoly were also undertaken at this time. These changes were widely welcomed (and widely criticized in antimodernist quarters), but what led to Godbout’s defeat in 1944 was his government’s insistence that it could obstruct conscription. Tied to that one issue, the government’s fate was all but sealed when Ottawa finally introduced conscription.

The 1944 election returned the UN and Duplessis with fewer votes than the Liberals but a modest majority of seats nevertheless. Duplessis’ bedrock of support was rural Quebec, where his antimodernist message had the greatest purchase. Even in the late 1930s, Duplessis was building a populist base, reinforced with attacks on the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Communist Party, both of which were despised by the Catholic Church. And a spell in opposition during the Godbout years helped him out: an outspoken moralist, Duplessis’ earlier term in office was marked by binge drinking and a reputation as what was then called “a lady’s man.” By 1944, he had dried out and was regarded as a reliable opponent of pro-conscription Ottawa and a champion of Quebec autonomy (autonomisme) within Confederation.

Post-War Quebec

Duplessis, who was nicknamed “Le Chef,” would hold on to office until 1959. During that 15-year era of relative prosperity and economic growth, the Union Nationale — like other populist parties in Canada — behaved in contradictory and sometimes confusing ways. While Duplessis sustained the ultramontanist elements within Quebec society and relied heavily on clergy support in rural areas, he also launched initiatives that gradually reduced Church control over education while increasing state involvement. It has been argued that shrinkage in the number of active clergy made this shift necessary, but it marks a sea change nevertheless. The UN was outspokenly a part of rural Quebec, but it also now invested heavily in hydroelectric infrastructure. It was traditionalist and simultaneously — perhaps unavoidably — modernist in some of its policies. But Le Chef’s anti-Ottawa, pro-rural, traditionalist posture tended overall toward a kind of isolationist parochialism. Rather than encourage Québecois investment in mines and the pulp and paper industry — let alone acting to create a state presence in those sectors — Duplessis encouraged foreign investment in industry. These Anglo-American operations provided only low-paying and low-status jobs for French-speaking Canadians and a fraction of the royalty revenues that were won in the same sector by other provinces. (In one dramatic case, Newfoundland was found to be taking nearly ten times the royalty revenue that Quebec won from the same iron ore body located on the Quebec-Labrador border.) Moreover, Duplessis was a social conservative whose social policies left Quebecers behind much of the rest of Canada when it came to welfare provisions. Nevertheless, the UN years saw an overall improvement in economic growth and, for once, the Quebec state system was able to dominate the clergy (to which it nonetheless continued to symbolically defer). This was all executed in an environment of systematized and extensive patronage that ensured loyalty to the party and to Le Chef himself.

Duplessis’ legacy has been the subject of repeated criticism in the decades since his death. Quebec nationalists dislike his anti-separatist stance, and liberals denounce his social conservatism. Some minorities resent the privileges he granted to the Roman Catholic Church, while other religious groups were actively or passively discouraged. His critics hold that his inherently corrupt patronage politics, his reactionary conservatism, his emphasis on traditional family and religious values, his anachronistic anti-union stance, his rural focus, and his preservation and promotion of Catholic Church institutions over the development of a secular social infrastructure (akin to that underway in most of the postwar western world), stunted Quebec’s social and economic development by at least a decade. It is for this reason that Duplessis’ term in office is sometimes described as the Grande Noirceur, black years in which individual liberties were reduced, corruption abounded, and Quebec stagnated economically.[2]

The Quiet Revolution

Regardless of Duplessis’ intentional legacy, it is certainly the case that his administration laid the groundwork for the era of accelerated reform that followed. In 1959, Duplessis died and was replaced by the ill-fated Paul Sauvé (1907-1960), who followed Duplessis to the grave the next year at 53 years of age. Sauvé’s brief tenure was marked by a severe change in UN direction. From 1944, Sauvé served as the Minister of Social Welfare and Youth (a position he continued to hold even as premier-designate), and his first steps in 1959 involved strengthening the public education system and envisioning, publicly, a changed Quebec society. Whether he would have achieved even a part of what he promised matters less than the fact that he urged upon Quebecers an attitude of transformation. The still shorter interregnum government of Antonio Barrette (1899-1968) fell to a revived Liberal Party led by Jean Lesage (1912-1980), campaigning under the banner, “Il faut que ça change” (“Things must change”).

Quebec in 1960 was not what it was in 1940. The population had grown from just over 3 million to 5.3 million, and the movement of people off the land and into urban areas rendered Duplessis’ agrarian focus obsolete. Sprawling, metropolitan Montreal in 1961 contained 2.1 million people, 40% of the province’s total population. Liberal Party support — and support for substantial social and economic change — was to be found in the politically powerful urban areas first and foremost. And it was there that modernization was most in demand. Improved educational and social welfare programs were a first priority, as was the nationalization of the entire hydroelectric sector, vastly increasing the capacity and reach of Hydro-Québec.

This prominent initiative was undertaken by the Minister of Hydraulic Resources, a former television journalist named René Lévesque (1922-1987). It represented such a substantial step in public policy that the Liberals called an election in 1962, only two years into their first majority mandate, on the issue of nationalization. They won only 5% more of the vote, but won 12 additional seats in the 95-seat National Assembly. This improved mandate was a signal that the key directions of Lesage’s proposed Quiet Revolution (Revolution tranquille) enjoyed broad support. The hydroelectric monopoly allowed the government to ensure that Quebecers had first call on construction-related jobs and that highly skilled francophones would not be denied management and technical positions as they arose. The crown corporation functioned in French first and was the centrepiece of a suite of policies aimed to achieve the Liberal goal: Maîtres chez nous (masters of our own house). Downstream benefits included a standardized pricing system that would attract industry and energy independence. The provincial government thereafter applied similar nationalizing models to other areas of their resource sector, increasing jobs and government revenue at the same time.

Educational reforms in support of this modernizing economic vision included improved access to state-run secondary education and an increase in the age of compulsory attendance from 14 to 16 years. These changes were meant to address the parlous levels of high school completion in Quebec — roughly half the rate found in English Canada in the 1950s — and to prepare a growing number of Québecois for technical careers. To that end, the old classical colleges were replaced with general and technical colleges, known as CÉGEPs. Most of these reforms were mounted in 1964.

The timing of education reform was significant. Removing the Catholic Church from its dominant position in education — sometimes referred to as declericalization — coincided roughly with the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II). Reforms in the Church at this time were extensive and the possibility of careers for nuns and priests as educators and health professionals was now in retreat. What’s more, Vatican II meant that the ultramontanist elements in Quebec found little favour in Rome. The Quiet Revolution was not going to be derailed by an interventionist Pope.

All of these changes combined to be revolutionary in the sense that authority increasingly resided with the state, not the Church; it was at home in the cities, not on the land. French-speakers were enabled and encouraged to become managers and directors rather than day-labourers. Francophone technocrats and planners acquired a new kind of prestige as leaders of change. The branchplant economy survived but it was increasingly challenged by homegrown industries and sectors. The Liberals could convincingly point to evidence that Québecois were, in fact, becoming maîtres chez nous. What’s more, they were exporting this pride: as early as 1961, the Liberal government opened its first trade houses or Maisons du Québec — embassies without diplomatic status — in London, Paris, and New York.

These advances and the rhetoric of nationalism, embraced by the Liberals and articulated by the nationaliste newspaper Le Devoir, was increasingly articulated in demands for greater autonomisme and, for the first time in many decades, separatisme.

Nationalisme, Autonomisme, Separatisme

The 1940s and 1950s witnessed the decolonization of much of Africa and Asia. As imperial forces withdrew from what were, mostly, nations conquered by European armies in the 18th and 19th centuries, some in Quebec began to question whether it was time to liberate New France. Fear of assimilation and English oppression was a driving force in Quebec politics from 1759 on. Two centuries after the Conquest, nationalistes (whose views were articulated in Le Devoir , which was founded in 1910 by Henri Bourassa) were increasingly unconvinced that the strategy of autonomisme implicit in Confederation was still a viable strategy for their community. The fact that most of the wealth in Quebec was thought to be in the hands of English-speakers (huddled in Montreal’s Westmount and in the Eastern Townships) led some Quebecers to conclude that Canada was an unequal bargain, a colonial relationship in which ethnicity, language, and religion worked systemically to the disadvantage of French-Canadians. One example will suffice: clerks in Montreal stores were obliged to speak English to their customers, regardless of the customer’s first language. How could this be experienced as anything other than colonization?

As well, the 20th century was bearing down on Canadien culture. The rise of electronic media like radio, movies, and television exposed francophones to an onslaught of images and values from English Canada and the United States. Antimodernists, of course, were particularly critical of this tidal wave of entertainment-culture and one response was to intensify relations with Metropolitan France, an option that had been largely closed off by years of ultramontanist hostility toward the French Republic. Modernists, for their part, saw in nationalized industries a means to advance Quebec’s economy and society but only if that could be done in a context in which francophones were no longer discriminated against when it came to top jobs. As regards Ottawa’s priorities and values in international relations, culture, trade, and even monetary policy, nationalistes believed those priorities did not reflect their own.

Several strategies to achieve change emerged in the early 1960s. The first of these was constitutional change. In order to address some long-standing concerns and immediate goals, there would need to be a means for amending the British North America Act. And, because the Act was a product of the British Parliament, there was the issue of patriation. Nine anglophone provinces and one francophone province, however, saw this process rather differently. The Fulton-Favreau Formula gained support at this time from every province but Saskatchewan; it proposed consensus agreement on issues involving all provinces, regional consensus or single-province agreement for more localized changes, and further subdivisions of process that made it, in the words of one constitutional expert at the time, “an unmitigated constitutional disaster.”[3] Nevertheless, opposition to Fulton-Favreau was limited and even Lesage supported it; that support quickly dissipated as nationaliste elements in Quebec became more vocal in their belief that this cumbersome system would more likely perpetuate rather than relieve the inequities of federalism.

If federalism could not be changed by its own institutions, it was argued, then Quebec needed to reclaim its pre-1867 authority (such as it had during the Confederation negotiations) or withdraw — entirely or in part — from the federation. This was a position taken along a spectrum of alternatives by diverse groups in Quebec in the early to mid-1960s. Conservative nationalistes — like the Alliance laurentienne, founded in 1957 – soon found themselves arguing different sides of the same coin with left-wing nationalistes. In 1960, the Rassemblement pour l’Indépendance Nationale (RIN) brought together the Alliance laurentienne with more moderate and, eventually, more radical left-wing nationalists inspired by the vibrant campus protests and anti-colonial movements of the time. The RIN engaged in electoral politics without success but maintained a high profile in public protests, such as demonstrations against the Royal Visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1964. When Pierre Trudeau — freshly appointed as Prime Minister designate — took a seat in the main viewing platform of the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day Parade in 1968, it was the RIN that mounted a noisy protest and threw objects at Trudeau. The leader of the RIN, Pierre Bourgault (1934-2003), was a participant in this last event and was arrested, along with hundreds of others. In the midst of these street-level confrontations, more moderate and conservative members of the RIN split off to form the Ralliement National (RN), another political party that would compete for separatist votes.

Further to the Left was the Action socialiste pour l’indépendance du Québec (ASIQ), the Réseau de résistance (RR), and the Comité de liberation nationale. These groups had closer relations with communist and anti-colonialist movements and took inspiration from the Algerian and Cuban revolutions in particular. While there was a tradition of civil disobedience in Quebec, this quickly became overshadowed by more violent tactics, including vandalism and destruction of federal property.

Beginning around 1967 to 1968, these diverse movements began to coalesce around two principal ideals and organizations. Those who favoured electoral strategies turned increasingly toward the new Mouvement souveraineté-association (MSA) led by René Lévesque, the former cabinet minister who abandoned the Liberal Party over the issue of significant constitutional change. The RN merged with the MSA in 1968 to form the Parti Québécois (PQ); much of the membership of the RIN joined as well when that party, too, was dissolved. The concept that Lévesque championed, called sovereignty-association, represented a compromise between continued, reformed federalism and full-blown independence. Quebec would, in this vision, become an independent and sovereign state but one with strong ties to the rest of Canada that bore some similarity to the arrangement struck between the Low Countries in Europe (called Benelux) and the European Economic Community (EEC).

The electoral separatism offered by the PQ was up against several more starkly nationalistic movements who were inclined to the view that change would not come through the ballot box. The Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) embraced guerrilla tactics being used by Palestinians in their struggle against Israel. It also took advantage of historical images of rebellion in French Canada, including the tri-colour flag used by Papineau’s 1837 Patriotes and the silhouette of an armed habitant from the 19th century Rebellions. Beginning in the spring of 1963, the FLQ launched a series of largely ineffectual bomb attacks. They targeted Canadian Army barracks and a length of rail line east of Montreal. The FLQ quickly graduated from Molotov cocktails to heavy explosives. In April 1963, a 65-year old custodian at a Recruiting Office was killed by an FLQ bomb, and a month later one of 11 explosives planted in post boxes severely injured an Army bomb-disposal expert. By the end of 1968, the FLQ could claim to have detonated close to 100 explosives of various shapes and sizes, all of which targeted federal property of some kind. They had, as well, engaged in a robbery spree calculated to get both money and arms for the movement. Along the way, the organization was responsible for the injury or death of at least four people. In other decades, this might have been enough to alienate support but conditions were different in the 1960s. The sustained support for the FLQ has to be understood within the context of growing opposition to the American war in Vietnam, the civil rights and Black Panther movements in the United States, increasing youth unrest on campuses, the spread of various liberation movements internationally (into which the FLQ networked), and the FLQ’s well articulated socialist objectives in Pierre Valliere’s 1968 book, Nègres blancs d’Amérique (translated as White Niggers of America).

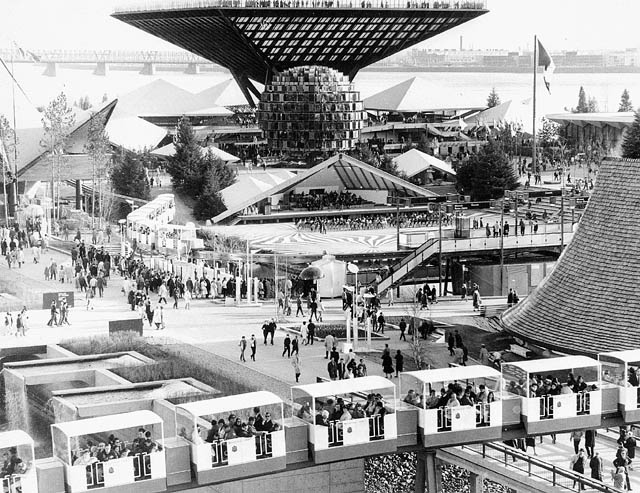

In 1967 and 1968, then, and at the height of Centennial celebrations in Montreal at Expo ’67, Quebecers found themselves confronted by political movements of an unprecedented kind. The terrorist campaign undertaken by the FLQ was decried by Lévesque and the PQ; the FLQ regarded the PQ as insufficiently aggressive in its objectives and techniques. The Liberal Party, for its part, retained an interest in renegotiating elements of the constitution should a satisfactory patriation formula be found. In short, everyone in Quebec politics agreed that change was necessary, but disagreed strongly on the extent of change and the means by which it would be achieved.

Gaullism

A wildcard in the separatiste deck was the French President, General Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970). Elevated to power during a coup d’état in 1958, de Gaulle viewed the English-speaking world with suspicion and hostility. Rebuilding an independent French military and financial powerhouse was his principal goal, and to that end he sought to diminish the strength of his competitors, chiefly the United Kingdom and the United States. Canada, which he understood first and foremost to be an English-speaking country, was a less critical impediment to French advancement, but it was a potentially useful stepping stone. By destabilizing relations between Quebec and the rest of Canada, he would destabilize North America as a whole. Keeping in mind that this was a decade that witnessed leftist revolutions in several countries, the idea of a radicalized, French-aligned, and nationalistic regime in Quebec would cause worry in Washington and Ottawa alike.

It was in this context that de Gaulle travelled to Canada in July 1967, ostensibly as part of the centennial celebrations and Expo ’67. Rather than head first to Ottawa, de Gaulle’s entourage landed at Quebec City and drove in a motorcade along the banks of the St. Lawrence — through the heart of old New France — along the route of the 18th-century highway, the Chemin du Roy. Passing throngs of French tri-couleur flag-waving Québecois, it has been suggested that de Gaulle might have been reminded of his own triumphal return to Paris in 1945 as the leader of the Free French. Whatever was on his mind — whether it was nostalgia, affection for Quebec, or causing a disturbance — on 24 July, he took to a balcony of Montreal’s City Hall and shouted to an ecstatic crowd, “Vive le Québec. Vive le Québec libre!” Then he went home without meeting any Canadian officials.

The role of France in stimulating French-Canadian separatism is difficult to measure. It was there before de Gaulle and it didn’t need French support to keep it alive. The distinguished Canadian historian, J.F. Bosher, has argued that Gaullists (de Gaulle’s followers in the Fifth Republic of France) conducted a kind of undercover and subversive operation in Quebec, providing resources and succour for a movement that might otherwise feel entirely isolated.[4] Whatever his motives, de Gaulle’s gun-and-run visit marked a dark day for Quebec federalists, excited support for the sovereigntist and separatist movements, and irritated English Canada.

Key Points

- Provincial politics in 20th century Quebec were distinguished by the importance of sustaining good relations with the Catholic clergy, addressing the needs of a large rural and anti-urban population, and struggling to preserve and advance francophone opportunities in an economy dominated by anglophones.

- The Conservative Party was rendered unelectable by the conscription issue in WWI and needed to reinvent itself as the Union Nationale in order to become an effective opponent of the provincial Liberals.

- The 15-year administration of Maurice Duplessis was viewed at the time, and since, by most historians as a period of antimodern, ultramontane, traditionalism, and/or a Grande Noirceur.

- The economic and social stagnation of the Duplessis years contributed to the appeal of significant change, embodied in the ideals of the Revolution tranquille, whose goal it was to make Quebecers maîtres chez nous.

- The Quiet Revolution included extensive state involvement in education and declericalization which coincided with Vatican II. It focused, as well, on providing greater middle- and upper-management opportunities for Québecois.

- Increasingly nationaliste elements identified the limits to change that could occur under the existing constitutional relationship with the rest of Canada. This produced an array of separatiste political parties and movements that coalesced around the Parti Québécois in electoral politics and the FLQ in direct action politics.

- Separatisme in 1960s Quebec occurred against a background of anti-colonial, civil rights, and guerrilla movements globally and in North America. The tone it took reflected its historic context.

Media Attributions

- Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis giving a speech © Library and Archives Canada (PA-178340) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Archidiocèse_Montréal

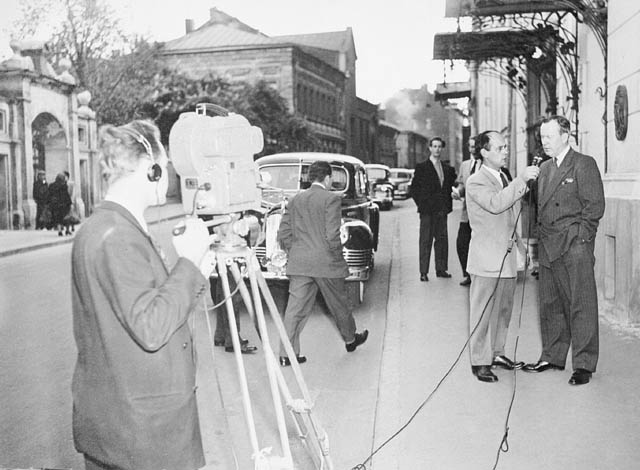

- René Lévesque, Radio-Canada reporter, interviewing Lester B. Pearson outside the Canadian Embassy in Moscow © Soviet, Library and Archives Canada (PA-117617). Copyright Soviet. No restrictions on use.

- Expo 67 Montreal, P.Q. © Frank Grant, Library and Archives Canada (C-030085). Copyright Government of Canada. No restrictions on use.

- Le-général-de-Gaulle-au-balcon-de-lhôtel-ville-de-Montréal-24-juillet-1967

- Richard Jones, “Gouin, Sir Lomer”, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 12, 2016, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gouin_lomer_15E.html. ↵

- Maurice Duplessis, Project Gutenberg, Self-Publishing Press: http://self.gutenberg.org/articles/maurice_duplessis CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Bora Laskin, quoted in Editor’s Diary, “The Search for an Amending Process, 1960-1967,” McGill Law Journal, vol.12, no.4 (1966-67): 345. ↵

- J.F. Bosher, The Gaullist Attack on Canada, 1967-1997 (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999). ↵

In Quebec, the period from 1944 to 1959 in which policies were introduced under the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis.

The imposition of state ownership over a corporation or sector; examples include the provincial nationalization of hydroelectricity providers (e.g.: Ontario Hydro, Hydro-Québec, and BC Hydro) and the water transport monopoly in British Columbia (BC Ferries).

A period of rapid and consequential change in the character of Quebec politics and society beginning in the late 1950s.

The slogan used by Jean Lesage’s Liberals in Quebec in 1960 election, ushering in the Quiet Revolution.

Publicly funded pre-university colleges in Quebec.

A movement to replace church authority with state authority in the running of schools and other institutions.

Convened by Pope John XXIII in 1959; ended 90 years of papal infallibility by opening dialogue regarding doctrine and the relationship between the Catholic Church and the modern world; upset many long-standing convictions about unchanging features of Catholic life; in Canada, contributed to the sense of social, spiritual, and secular fluidity that was bound up in the Quiet Revolution.

The transfer to Canada from Britain of the British North America Act (an Act of the British Parliament) and thus enabling its amendment in Canada.

A formula for amending the British North America Act (1867) developed in the 1960s; rejected by Quebec in 1965; provided the framework for subsequent discussions in 1982.

A 100th anniversary; in Canada, is used as shorthand to refer to the 1967 celebration of 100 years of Confederation.

A “World’s Fair” held in Montreal in 1967; part of the Centennial celebrations.