Prewriting: Ground Zero

17 Appealing to Your Audience

Once you know who your intended audience is and what your purpose is for writing, you can make specific decisions about how to shape your message. No matter what, you want your audience to stick around long enough to read your whole piece; you appeal to them. You get to know what sparks their interest, what makes them curious, and what makes them feel understood.

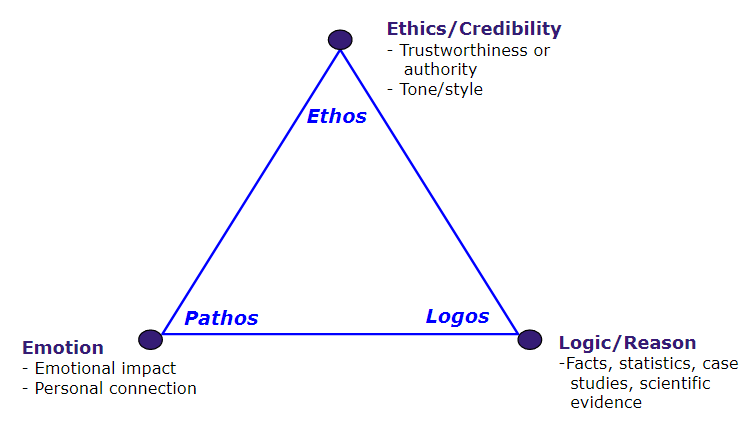

The Greek Philosopher Aristotle provided us with three ways to appeal to an audience, and they’re called logos, pathos, and ethos. You’ll learn more about each appeal in the discussion below, but the relationship between these three appeals is also often called the rhetorical triangle, and in diagram form, it looks like this:

Pathos

Latin for emotion, pathos is the fastest way to get your audience’s attention. People tend to have emotional responses before their brains kick in and tell them to knock it off. Be careful though. Too much pathos can make your audience feel emotionally manipulated or angry because they’re also looking for the facts to support whatever emotional claims you might be making so they know they can trust you.

Logos

Latin for logic, logos is where those facts come in. Your audience will question the validity of your claims; the opinions you share in your writing need to be supported using science, statistics, expert perspective, and other types of logic. However, if you only rely on logos, your writing might become dry and boring, so even this should be balanced with other appeals.

Ethos

Latin for ethics, ethos is what you do to prove to your audience that you can be trusted, that you are a credible source of information. (See logos.) It’s also what you do to assure them that they are good people who want to do the right thing. This is especially important when writing an argument to an audience who disagrees with you. It’s much easier to encourage a disagreeable audience to listen to your point of view if you have convinced them that you respect their opinion and that you have established credibility through the use of logos and pathos, which show that you know the topic on an intellectual and personal level.

Here is a video titled “Aristotle’s Rhetorical Triangle” (07:28) about rhetorical appeals that goes into more detail about the three appeals and how Aristotle used the rhetorical triangle to illustrate the relationship between the appeals and the audience.

Narrator: Aristotle believed that rhetoric was the counterpart of dialectic, the means by which we arrive at the truth, and that the truth needed to be defended by those skilled in rhetoric. Aristotle divided every persuasive occasion into three broad categories, which he shaped into a triangle. Think of it as the tri-force of argumentation. The first element is the speaker, the second, the message, the third is the audience. Let’s begin with the speaker.

What every speaker needs to strive for is ethos. It’s what makes them worth listening to. It’s their credibility based on the occasion. This element can be subdivided into five broad categories.

- One way to establish credibility is to appear knowledgeable to the audience. Now this isn’t just a spouting of facts. You must seem to know the relevant information that is pertinent to the issue.

- Another way to gain credibility is to appear virtuous. Now this isn’t always based on the traditional [inaudible] of virtues. What this really calls for is to have the qualities that are more important to the audience based on the occasion. For example, a thief who is persuading a den of thieves to follow his plans will be better off displaying his cunning and ruthlessness rather than honesty and purity.

- Yet another way to gain your audience’s trust is to make them aware of your experience. Think of every teacher or professor you’ve ever had that spent the first day of school recounting their years of experience and academic feats.

- Another way to earn trust is to show credentials. Degrees and credentials are worthy of display in many offices. I particularly derive comfort from them when displayed in a doctor’s office. Badges are wonderful on police offices, and uniforms are good on store employees.

- Last, but definitely not least is good-willed, or good intentions. If you appear to show that you only have the best interest of the audience at heart or at the very least that you are disinterested in personal gain, then the audience will be more likely to hear you out.

If you can show to the audience that you have all of these types of this credibility, then they will give you their attention, they will open up their ears to you and hear you out.

Of course, all of this will only work if it is appropriate to the occasion:

- Audience: It might not be useful to show off your knowledge by showing statistics to a five year old, especially if you are trying to convince them to eat their vegetables.

- Issue: And as much as I trust doctors to work on my body, I don’t automatically assume an MD is indicative of a master chef.

Our next major element is the message. The message should be constructed around logos, or logic, in mind. At least, it must structurally have the veneer of logic to win over an audience worth winning over.

One way to structure a message is to being with a specific example, fact, or what counts as evidence in the occasion and then draw a conclusion from this specific proof.

Example/Proof → Conclusion — y so x

Mr. Abuel killed a student , so he should go to jail.

Another way to structure a message is to begin with a major premise, some common assumption about life, and then draw a conclusion appropriate to the occasion. There are more complicated structures, but these should do for now.

Premise/Reason → Conclusion — z so x

Killing is wrong, so Mr. Abuel should go to jail.

With this, you should have gained entry in to the audience’s brains, which is really helpful in changing the way they think.

Our final element is the audience, and what is the most important—according to Aristotle —is to move their hearts, which you should have access to by now if you have their eyes and ears (gained through ethos) and their brains (gained through logos). Now, we can travel to their hearts, which is the ultimate decision maker.

We can rouse either positive feelings or negative feelings, though bear in mind that what I am defining as positive are feelings that tend move the audience towards the target and negative feelings are what would repel the audience from a point.

| Positive Feelings | Negative Feelings |

|---|---|

| Love, satisfaction, anticipation, useful, patriotism, humor, attraction, contentment, pride, safe, desire, wonder, joy, affection, important | Hate, sad, resentment, disappointment, anxiety, shock, envy, aversion, shame, disgust, fear, guilt. |

These feelings are not good or bad to the rhetorician. They are merely tools to achieve a goal.

Examples:

- Patriotism: “It would be the American thing to do…”

- Desire: “Think about it. Money, fame, love, and power. It can all be yours if you simply…”

- Fear: “If you do it, you’ll end up getting killed or even worse!”

- Guilt: “And because you were too selfish to give money, they all ended up starving.”

One modern theory that is particularly useful for giving the rhetorician ideas for pathos is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Look this up for clarification.

| Self-actualization | Morality, creativity, spontaneity, problem solving, lack of prejudice, acceptance of facts. |

| Esteem | Self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect of others, respect by others. |

| Love/belonging | Friendship, family, sexual intimacy. |

| Safety | Security of body, employment, resources, morality, the family, health, property. |

| Physiological | Breathing, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, excretion. |

Of course, the idea would be to mix all of these ideas together for maximum efficiency: gain credibility through the virtue of your message while at the same time moving the passions of the audience.

My example clearly does not do this. *Sigh*

So what is the function of all of the rhetorical appeals? The end goal is to use your words to change how people think, understand, believe, and feel on a given set of issues. This is to prepare them for what is ultimately most important.

Words change very little, but what they can change are the little things that prepare a person for action or non-action.

[End of transcript]

For more on appealing to your audience, also see “Imagining Your Audience’s Needs.”

Image Descriptions

Figure 1 image description: A 3-point equilateral triangle with Pathos, Logos, and Ethos labelling each point. Pathos refers to emotion, including emotional impact and personal connection. Logos refers to logic and reason, including facts, statistics, case studies, and scientific evidence. Ethos refers to ethics and credibility, including trustworthiness or authority, tone, and style. [Return to Figure 3.1]

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from “Appealing to Your Audience” in The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Licence. Adapted by Allison Kilgannon.

Media Attributions

- Aristotle by Jastrow is in the public domain.

- “Logos, Pathos, Ethos Triangle” by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Licence.

Video Attributions

- “Aristotle’s Rhetorical Triangle” video by Sigfried Abuel. Licensed under a CC BY-NC 3.0 Licence.

- “Aristotle’s Rhetorical Triangle” video transcript was adapted from the original video by BCcampus. Licensed under a CC BY-NC 3.0 Licence.