16 Developing Good Governance

Learning Outcomes & Big Ideas

- Distinguish between environmental conflict and environmental insecurity, using concrete examples.

- Describe how the environmental security of a population, community, or country can be increased.

- Discuss how ecocentric thinking can be useful in the pursuit of environmental security, even though the latter is an anthropocentric concept.

- Critique the conventional interpretation of sustainable development as it is represented in the Brundtland report.

- Give some examples from your own country that illustrate the influence of weak interpretations of sustainable development in government policy.

- Describe the principles of good environmental governance using examples (real or hypothetical) of policy decisions.

- Describe how your personal values reflect (or how they could be changed to reflect) at the personal and external levels the ideals of Earth democracy.

- Explain how the principal values in the Earth Charter support good governance.

Summary

The consequences of excessive consumption and resource exploitation at the global level are growing inequity and environmental degradation. Each of these two factors amplifies the other, leading to a ‘double exposure’ of spiralling insecurity. The mutual reinforcement between these trends can only be interrupted if active steps are undertaken towards environmental security.

The problem with conventional interpretations of sustainable development is that they do not promote environmental security. Reasons include the separation in space and time between perpetrators and victims; the inability to arbitrate between economic, social, and environmental agenda in the popular ‘triple bottom line’ approach; and the indiscriminate claim that all humans, present and future, can ‘have it all’ without attention to the requirements. Underneath that convention lies a weak model of sustainability that regards the natural environment as ‘the other.’ Conversely, workable “strong” definitions of sustainability and sustainable development must rest on the primacy of ecological integrity as a requirement for environmental security and thus human security.

Current models of governance rest on the weak model of sustainability, as far as they recognise its importance at all. This indicates a failure of states and of citizens in exercising their responsibilities. Good environmental governance would be based on the strong notion of sustainability and on a non-anthropocentric responsibility and care for the community of life. Its normative principles include respect for ecological integrity in decision-making; intra and inter-generational equity; the precautionary principle; internalization of environmental costs; and responsibilities of guardianship. It also employs the process principles of transparency, participation, and accountability, and in order to achieve good environmental governance, the global civil society (NGOs) needs to extend from NGOs to include entire electorates and to get them to accept their responsibility to ensure human security. This requires a model of Earth democracy that relies on a profound normative change.

The Earth Charter outlines a blueprint for Earth democracy and global environmental governance (Earth Charter Initiative 2000). It consists of four themes that form the foundation for a global sustainable society: respect and care for the community of life; ecological integrity; social and economic justice; and democracy, non-violence, and peace. It does not address methodologies and arbitration of contradictions. Subsequent steps include a global constitution and the entrenchment of sustainability in international law.

Chapter Overview

16.2 Sustainable Development and Human Security

16.3 The Principle of Sustainability

16.4 Governance for Sustainability

16.4.2 Current Models of Governance

16.5 The Role of Civil Society

16.5.1 Earth Democracy and Earth Trusteeship

16.5.2 A Norm of Ecological Citizenship?

16.6 The Earth Charter: A Framework for Global Governance

Extension Activities & Further Research

16.1 Introduction

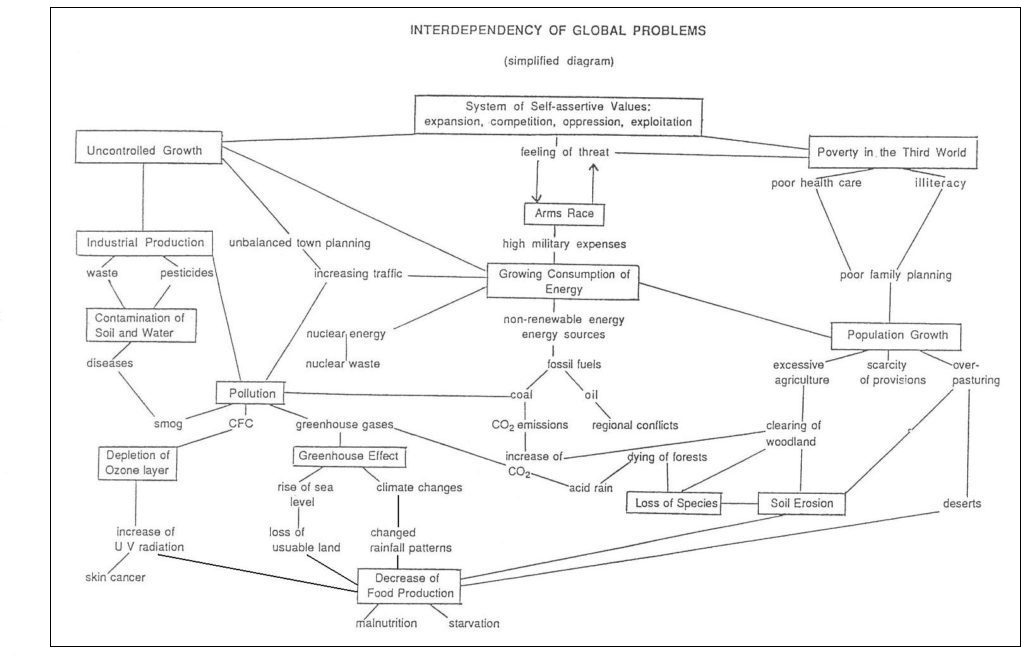

The concept of ‘human security’ has expanded conventional visions of security beyond the sovereign state actor, national interests, militarism and warfare, to also include the multitude of other threats experienced by individual human beings and their communities (Shani, 2007; see also Chapter 1 and Chapter 3). The term was first articulated in 1994 by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in the annual Human Development Report which identified seven categories of threats to human security: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political. The concept transforms both the referent objects of security and the means of achieving security from states to humans, and from military action to human development (UNDP, 1994, p. 24). The UNDP defines human security as ‘freedom from fear’ and ‘freedom from want’ (UNDP, 1994). The UNDP concept of human security reflects the split focus in human rights discourse between civil and political, as well as between social and economic (development) concerns (Shani, 2007). It draws previously distinct issue and policy areas into a common discourse, principally concerned with human well-being. This reconceptualization can be seen as an acknowledgement of the interdependency of global problems. Ideally this holistic approach to human security would provide an invitation for innovative inter-sectoral cooperation and integrated policy responses (Tadjbakhsh & Chenoy, 2007; Cherp et al., 2007). Accordingly, the UNDP advocates ‘sustainable human development’ as the means of addressing the various threat areas (UNDP, 1994).

In his article “The Coming Anarchy”, Robert Kaplan (1994) wrote “it is time to understand the Environment for what it is: the national security issue of the early 21st century.” (Kaplan, 1994, p. 54). But beyond being merely another national security issue, human security is concerned with both personal violence and ‘structural violence’ (Galtung, 1969; Tadjbakhsh & Chenoy, 2007; Barnett, 2007). In what Eriksen (2010) calls a shift to a qualitative approach, security can no longer be viewed objectively as merely the absence of violence. Rather, security is subjectively determined and refers to the various locally experienced social, economic, and environmental realities that affect human well-being (Eriksen, 2010, p. 1; Voigt, 2008, p. 187). The shift recognises the limitations of traditional conceptions of security to fully capture the human (men and women) experience and mirrors the issues raised by critical security and gender scholars (Detraz, 2010).

In view of the attention being given to the links between the environment and human insecurity, two concepts warrant mention in the context of this chapter. The first, environmental conflict, refers to the conflict over resources (Detraz, 2010). As Kaplan envisioned, this concept reflects traditional notions of security with the environment being viewed as an ‘interest’ to be pursued through national security. Environmental security, on the other hand, refers to the impact of the environment on people (Detraz, 2010). This might include the impact of man-made degradation and natural disasters. Related to both these concepts is also the impact of warfare and conflict on the environment (Hulme, 2008).

In his discussion of environmental security, Jon Barnett (2007) identifies the impact of environmental change on human wellbeing as a form of structural violence. Vitally though, he demonstrates that the environmental ‘threat’ is essentially caused by humans beings. Barnett (2007) explains how patterns of consumption and resource exploitation in pursuance of industrial capitalism in the developed world have two effects. First, they are the cause of social injustice — an ever widening gap between rich and poor, developed states and developing states, often referred to as the north–south gap. Second, the impact on ecosystems has resulted in unparalleled environmental degradation. Climate Change, biodiversity loss, land and forest destruction, resource depletion, air, soil and water pollution are among the myriad of environmental issues we are currently facing. People in poorer, developing states lack material and social ‘adaptive capacity’ to cope with environmental changes and hence social injustice and anthropogenic environmental degradation combine to have an even greater impact on human well-being in less developed states. Not only are the impacts disproportionately felt, but environmental degradation further exacerbates structural violence (Barnett, 2007). This cyclical illustration of human insecurity is labelled “double exposure” by O’Brien and Leichenko (2000). Such examples allow us to begin to see the rationale of the human concept of security confronting multiple, interconnected issue areas (O’Brien & Leichenko, 2000).

Voigt (2008) explains how environmental factors act as “tipping points.” Environmental change acts as a “threat multiplier” because the effects of shortages (of food, water, and other resources) lead to, and intensify, poverty and migration, which in turn has social and political implications (Voigt, 2008; European Commission, 2008). Environmental problems increase the risk of tensions, instability, and intensify existing conflicts in fragile areas (Cherp et al., 2007; Voigt, 2008; European Commission, 2008). Moreover, structural violence also leads people to engage in unsustainable practices and resource use – attempting to develop but being unable to do so sustainably because of an inability to meet even basic needs. We can understand then, why Barnett describes environmental insecurity as “the vulnerability of individuals and groups to critical adverse effects caused directly or indirectly by environmental change” (2007, p. 5). Conversely, ‘security’ includes adequate provisions for adaptation or prevention so that changes exert limited impact on well-being (Barnett, 2007).

What is problematic about this definition is that if we were to take Barnett’s definition of security and apply it to the global south it would mean enhancing the adaptive ability of the global south to environmental changes. Barnett illustrates the problem but in his conception of security he does not confront the fact that increasing the adaptive capacity of the developing world is futile so long as unsustainable consumption and growth continue unabated to create conditions of degradation and social injustice. Any definition of security is incomplete unless it acknowledges the necessity of addressing the status quo. We need to modify the concept in order to make sense of the link between the environment and human security.

Ecological security is concerned with the negative impacts of human behaviour on the environment (Detraz, 2010). Such a concept of security requires the preservation of ecosystems for their own sake, not only for their usefulness to humans (Liftin, 1999). This definition contains the recognition that since the environment is the referent object of security ultimately human beings, as part of ecosystems, are also referent objects. The security of human beings is premised on ecological security — that is, the viability of the biosphere. Social and political variables in human insecurity cannot be addressed unless the very basis of human life, the environment, is secure. Therefore, at the very heart of achieving human security is the need to address humans’ relationship with nature (Myers, 1993; Detraz, 2010; Page & Redclift, 2002). To exclude this relationship would reproduce the imbalances that cause environmental crisis, structural violence and their mutually reinforcing negative consequences for overall human security (Voigt, 2008, p. 167).

16.2 Sustainable Development and Human Security

The UNDP envisioned “sustainable human development” as the means to achieving human security (UNDP, 1994). Unlike conventional approaches to security, this approach appreciates that security depends on long term conditions for human well-being, realized in various interconnected areas. It is an application of the model of sustainable development stated in the 1987 Brundtland Commission Report ‘Our Common Future’ and reaffirmed at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

Sustainability as a basis for humans’ relationship with the environment is an ancient idea and has a history of successful implementation in public systems according to the ecological conditions of the time (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 3, 83; Weeramantry, 1997). The turning point in the relationship was the industrial revolution where humans’ perception of nature changed from recognising the intrinsic value and integrity of ecosystems to viewing nature as a machine and as a resource base to be exploited for human gain and prosperity. Importantly, this was also the era of private property and the diffusion of liberal economic free-market enterprise giving rise to “a relationship of individual power over the land” (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 13).

The first reference to sustainable development occurred in the 1980 World Conservation Report of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Then the World Charter for Nature, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1983, included a model of sustainable development in which the management of natural resources was deemed necessary in order to “achieve and maintain optimum sustainable productivity” (para. 4) but not “in excess of their capacity for regeneration” (para. 10a). This model reflected the sustainability dimension that “every form of life is unique, warranting respect regardless of its worth to man” (preamble). However in the 1987 Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987) sustainable development lost its core ecological meaning due to the development concerns and lobbying efforts of ‘southern’ states in the World Commission on Environment and Development (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 26). The priority of human needs was upheld. Then in 1992 the Rio Declaration was adopted as a non-binding agreement during the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), which states as its first principle that “human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development” (Principle 1; UNDP, 1992).

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence of unparalleled anthropogenic environmental degradation, patterns of wasteful production and consumption remain deeply ingrained in human behaviour (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 9). The continuance of these attitudes and behaviours is largely due to the externalization of the costs of environmental change. The negative consequences of current practices are often less likely to affect the human security of those causing the most degradation. They are separated by distance in space because these socio-economic activities take place globally, and they are separated in time because the effects of degradation primarily affect the resource base of future generations rather than their own. Hence, the demands of the current generation exceed the regenerative ability of nature (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 9).

Sustainable development has been presented as a three pillar model in which environmental, economic and social needs are all balanced (OECD, 2005). Sustainable development moved away from the intrinsic value of nature and became terminologically vague so as to simply maintain the status quo despite the irrefutable knowledge of how this negatively impacts the environment. Ways of protecting the environment were mainly informed by technical solutions and economic models, which resulted in environmental problems being simply co-opted into the current economic world order, without actual cognizance of what is being secured and what endangerments it is being secured against (Dalby, 2002). Thus the model of sustainable development in the Brundtland Report (1987) and its three pillars is an attempt to ‘have it all’ — economic prosperity and a healthy environment.

The vagueness of the UNDP (1994) formulation of sustainable human development means that we cannot even be sure whether concern for the environment actually features as a balance to development in other areas, or whether the environment is viewed purely as a threat. Much depends on how the relationship between environment and security is perceived. The difference between strong and weak sustainable development is that the environment is conceived either as ‘everything’ or as ‘the other’ (Bosselmann, 2006, p. 44). The human security literature, with its many equally weighed threat sources, largely reflects a limited understanding of the environment as a basis for insecurity. As a means of ensuring human security, this weak model of sustainability (as it has been referred to), is insufficient. Sustainable development, as it is now understood, is based on the irrationally held assumption that growth of human populations and economies can be reconciled with environmental preservation (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 2, 41).

Sustainable development and indeed the satisfaction of human security are inevitably about human needs. Human security recognises the needs of current and future generations to be free from fear and want, which reflects the notion of sustainable development proffered by the Brundtland Report: “the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987, p. 43). So, we are left wondering what needs these may be since the effects produced by interconnected threats to human security will surely adjust across time (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 28). Fundamentally though, the ability of future generations to be free from insecurity and to satisfy their material needs will depend on basic environmental services, without which no human life is possible (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 29). Fear and want can only ever be met within ecological boundaries — “there is no alternative to preserving the Earth’s ecological integrity” (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 2, 28).

16.3 The Principle of Sustainability

As we have seen, if sustainable human development is employed as the guiding objective behind revolutionary approaches to human security it does not go far enough, and expanding the sources of human insecurity is meaningless unless we genuinely call into question the very basis for our perceptions and behaviour in the world. For those people in the developing world to whom poverty is a pervasive security threat the pursuit of social justice and economic improvement are not only valid goals, but essential. However, “if we perceive human needs without regard to ecological reality we are at risk of losing the ground under our feet” (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 31). If human security is truly concerned with the security of future generations then the environment must be the underlying consideration in any of its paradigms. Without the realization that ecological integrity is paramount, social and economic interests have nowhere to go and justice and security will remain elusive (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 21). Only with the principle of sustainability can we establish a means of ‘doing’ security which can lead to genuine, lasting human and ecological well-being.

The principle of sustainability thus reflects the idea of ‘strong’ sustainable development — development that does not undermine ecological integrity (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 52). Instead of three pillars, ‘strong’ sustainability follows a ‘temple of life’ paradigm wherein ecological integrity is the foundation, social and economic welfare the two pillars, and cultural identity the roof (Bosselmann, 2008). Fundamental to this is the understanding that economic growth conflicts with ecological sustainability. Economic ‘rationality’ assumes a patriarchal and dominating relationship over nature. The principle of sustainability encompasses the idea of Johann Gottfried Herder, of the Earth as “wohnplatz” or a living space or house (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 19). Humans’ role as housekeeper and guardian of future generations is an idea reflected in various ecologically oriented societies (Manno 2010). In Maori culture the people are kaitiaki — stewards — of natural resources. For them the relationship is not one of patriarchal dominance but preservation of the ecological integrity of nature, and is guarded through means such as a “rahui” — ban — which can be placed over a resource to prevent use beyond its regenerative capacity. This idea of living from the yield rather than the substance is aptly illustrated (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 20). The economy is a sub-discipline of housekeeping; a nested egg rather than a parallel pillar (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 19; Bosselmann, 2013, p. 104), and to allow the interests of those dealing in the extracted value of nature to dominate over the well-being of nature itself is irrational. Hence sustainability is not a suspicious rejection of progress but “in its most elementary form [it] reflects pure necessity” (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 8).

As mentioned, ecological insecurity is the result of a dysfunctional relationship between humans and nature. As a means to achieving ecological and human security, sustainability requires essentially an ethical discourse about values and principles (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 8). The principle of sustainability is an appropriate guide for present and future security because it focuses on the common essential elements of all life (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 29). The challenge for creating lasting security is to ensure that the principle of sustainability is firmly embedded in good global governance.

The opportunity to secure this principle internationally was missed at the 1992 UNCED conference in Rio, where no definition and no binding treaty for sustainable development were achieved (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 32), and with states proving ineffective as drivers to re-integrate the principle of sustainability into sustainable development thinking, another driving force is needed — civil society. At the 1992 Earth Summit NGOs and civil society groups formed the “Global Forum” alongside the conference and identified the necessary connections that were omitted in politicized state documents: “ecological sustainability was referred to as central to everything: poverty eradication, socio-economic development, human rights and peace” (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 32). Work began on creating an Earth charter to elucidate respect and care for the community of life and ecological integrity. The Earth Charter, launched in 2000 at the Peace Palace in The Hague and created solely by civil society groups, “represents a broader consensus on the principle of sustainability than has ever been achieved before” (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 34). The Earth Charter was endorsed by over 1000 NGOs at the Millennium NGO Forum, and despite the absence of any specific reference in the Johannesburg Declaration of the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) (2002), the language used therein is almost identical to the Earth Charter — notably referring to the “community of life.” Although the Johannesburg texts are vague, there is a heightened sense of ecological responsibility, signalling a move beyond mere social and economic foci into an ethical understanding more aligned with the principle of sustainability (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 34). This shift in ethical awareness was further strengthened at the 2004 IUCN World Conservation Conference where a resolution endorsing the Earth Charter as an ethical guide and an expression of vision was adopted by 67 of the 77 attendant states and 800 NGOs.

16.4 Governance for Sustainability

Then the vital question is, how do we shift from the status quo model of anthropocentric environmentalism, which is subsumed within the neoliberal economic agenda, to an understanding that is based on the principle of sustainability? One answer lies in creating systems of good governance at local, national and global levels wherein the underlying concern is protecting the integrity of the Earth’s ecological systems as essential to all other human concerns (Bosselmann, 2008). We need governance for sustainability (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 191; Bosselmann et al., 2008).

16.4.1 What is Governance?

Young (1997: 4) defines governance as “the establishment and operation of social institutions—in other words, sets of rules, decision-making procedures and programmatic activities that serve to define social practices and guide these interactions.” Governance does not require organizations or government per se, although these certainly help to facilitate actors into coordinated, cooperative decision-making (Young, 1997). A need for governance arises out of interdependence and the understanding that the actions of one affect the welfare of others (Bosselmann et al., 2008; Young, 1997). Therefore, good governance aims to ensure that people can organize their affairs in the most effective way (Young, 1997; Bosselmann, 2008). At the international level, regimes are systems of governance in specific issue areas, usually with states as members, and founded on constitutive documents, binding or non-binding (Young, 1997).

16.4.2 Current Models of Governance

The two central problems with current forms of governance concern their ethical basis and their institutional arrangements. Current models have been borne from western values and from priorities such as neoliberal economic ‘rationality’ and consumption (Bosselmann et al., 2008). Economic ‘rationality’ is regarded as the basis of ethics of governance and this pervades all of its levels (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 205). Even ‘weak’ sustainable development models are a relatively new inclusion in regime design, where ultimately the neoliberal conception of justice as property rights and mutual advantage prevails over other long term goals of social equality, human security and ecological sustainability (Okereke, 2008; Bosselmann, 2010a; Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 9, 102). Okereke (2008) explains how current forms of environmental governance are dominated by the neoliberal agenda and that ‘ecological modernization’ as the status quo is the solution to environmental problems. This is essentially ‘defensive, reactive, expert-based, problem solving’ governance which attempts to dampen calls for normative change within the neoliberal framework for sustainable development; essentially, it is expected that technological solutions, economic instruments, and government voluntarism will facilitate uninterrupted growth (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 205; Okereke, 2008). For the future of ecosystems, this reads that “our present form of governance finds care for ecological integrity too costly” (Bosselmann, 2008, p. 329). Current forms of international environmental governance “aim…to preoccupy and pacify aggrieved sections of the international community while leaving the fundamental structural causes of environmental injustice unchanged” (Okereke, 2008, p. 182).

As in the mainstream model of sustainable development, the design of our governing institutions reduces ‘the environment’ to a concern alongside other ‘competing’ concerns—an agenda distinct and usually subordinate to growth, productivity and profit (Bosselmann et al., 2008; Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 88, 125, 172). Yet, the noticeable change in focus of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) from ad hoc solutions to more comprehensive treaties should be seen as an attempt to strengthen forms of international cooperation (Roch & Perrez, 2005). The international environmental regime is still hampered by fragmentation and by a lack of synergy between agreements and issue areas. It is institutionally weak because the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) lacks the authority, membership and resources to provide comprehensive policy guidance (Roch & Perrez, 2005). Within this context we can understand the terminological vagueness and lack of binding international agreements (and the lack of ratification and implementation of those agreements that are binding) as a deliberate tactic to keep environmental governance peripheral to more immediate concerns. Roch and Perrez (2005) describe an ‘institutional imbalance’ between the environmental regime and other regimes (trade, finance), caused by a lack of procedural mechanisms, resources and most importantly, political weight. These realities at the international level reflect similar patterns at the domestic level. Current models of governance are designed to “maximise human freedom to use the Earth, intervening only when that use threatens or undermines the rights of other humans” (Bosselmann, 2008, p. 324). And even then, some human security scholars might argue, the ever widening gap between rich and poor seems to suggest this might be the exception rather than the rule.

Good environmental governance demands a sound management system for the environment. In light of what amounts to current management “there is little dispute that better governance is required.” However it is “a precise definition of what this means or what it required that is elusive” (Elliot, 2004, p. 94).

Governance for sustainability, as a means to ensuring human security, is about establishing core ecological ideals as the building blocks of any solution to human problems. Central to this project will be establishing the strong model of sustainability as a meta-narrative in all areas of social, political, economic and environmental interaction. Sustainability, that is the perspective of the whole Earth community, must be the reference point in much the same way as foundational ethical ideas such as justice inform a legal system (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 206). The idea of ecological justice and the principle of sustainability are sufficiently clear to serve as guiding principles of law (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 9, 126; Bischoff, 2010). Human security is about securing daily living by mitigating the threats to lives and livelihood (Tadjbakhash & Chenoy, 2007). This can only be achieved through a profound shift in thinking to an ecological, life-centred perspective that appreciates the health of the planet as the first step to secure human lives (Bosselmann et al., 2008; Bosselmann, 2008). The immediacy and diversity of individual human security is linked to the commonality of the threat of environmental breakdown. A credible model of governance must reflect the global nature of this problem (Bosselmann et al., 2008). Consequently a system of good governance cannot be western, nor can the subjects be limited to human life (Bosselmann, 2008). Good housekeeping is the preservation of all communities of life. Hence governance for sustainability is value based and about a holistic awareness that non-anthropocentric responsibility and care for the community of life is central and vital if humans are to function as productive ‘beings’ (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 96, 131, 204; Bosselmann, 2008). We can summarise the normative principles of sustainability as follows: considering ecological integrity in decision-making; intra and inter-generational equity; the precautionary principle; internalization of environmental costs; and responsibilities of guardianship (Bosselmann et al., 2008).

Good environmental governance will need to be multidimensional. The building blocks are principles, rules, norms and practices—a robust ethical foundation. This begins with people. Similarly, institutions are an important part of ensuring procedures for the formulation and implementation of policy. Finally agreements and established policies are important as guides and measures in compliance (Weale et al., 2000). Similarly, advancing sustainability will require openness, participation, accountability, predictability and transparency of institutions. To achieve governance for sustainability we need to integrate different areas of governance; we need governance which is multi-level, incorporating actors at all levels: corporate, local, national, regional and global (Bosselmann, 2010a). Only through a multi-dimensional, multi-level governance framework will contemporary security and survival issues be adequately addressed (Voigt, 2008; Bosselmann et al., 2008). The system wide problems of environmental degradation and the direct and indirect consequences for human life need to be confronted by broad principles of law, not issue specific legal and policy regimes, as is the current approach (Young, 1997). Multi-level governance requires a commitment from states and from citizens; “only a common effort by those who govern and those who are governed could bring about the necessary behavioural changes” (Bosselmann, 2010a, p. 93). Effective policy-making is a combination of effort from the governed (citizens) and the governors (states) (Bosselmann et al., 2008).

16.5 The Role of Civil Society

Judge Weeramantry (1997) famously called sustainability foundational to civilization. What is particularly alarming about the current environmental crisis is that people are profoundly aware that their current behaviour is illogical, yet lack the vision and the motivation to address it (Bosselmann & Engel, 2010). In the years since sustainable development first entered the international arena, the resultant lack of solid commitment from states — even to the ‘weak’ model of sustainability — demonstrates how the “world today is even further away from effective global governance than two decades ago” (Bosselmann & Engel, 2010, p. 15).

The failure of current environmental governance cannot be seen as purely a failure of states. Even in the unrealistic event that states and policymakers wholly embraced sustainable development and decided to issue a radically new national policy agenda the effect would be short lived. Individual behaviour is extremely difficult to regulate when it has deeply held normative foundations (Vandenbergh, 2004). States are the sum of their constituent populations and their lack of commitment reproduces the broader complacency of civil society. Democratic governments are elected by the demos — citizens (Bosselmann, 2010a). Hence “it is only by virtue of citizens that governments are able to reaffirm the idea of economic growth… missing the point of sustainability” (Bosselmann, 2010a, p. 97). This means that “civil society can either be indifferent or proactive with respect to sustainability” (Bosselmann, 2010a, p. 97).

Importantly this illustrates that norms and institutions are socially constructed. The prevalence of economic rationality as the normative basis and the source of institutional bias is historical, and for this reason it can be changed (Bosselmann, 2010a). The question is how to change it. Essentially the future of ecological wellbeing (and thus human survival, security and well-being) comes down to choice.

For this reason the success of the principle of sustainability will rest on how it is “(re)discovered, explained, defined and applied” and conceived of at the level of basic values (Bosselmann, 2017, pp. 4, 10). If current models of environmental governance are lacking then the onus is ultimately on civil society to be the vehicle for change (Bosselmann, 2017, p. 4; Bosselmann, 2010a). All institutions and forms of governance take their mandate from citizens acting individually as well as cumulatively, so civil society will determine whether and to what degree public concerns enter the democratic process (Bosselmann, 2010a). A fundamentally new mindset must be catalysed (Voigt, 2008). The real challenge then, and the vital element of moving forward toward ecological sustainability and overall human security, is how to shift the attention of governance from the status quo to ‘strong’ sustainability (Bosselmann, 2010a).

16.5.1 Earth Democracy and Earth Trusteeship

Although global civil society has been instrumental in the promotion of sustainability values, there is a disjoint between the mobilised and ecologically aware elements of that society that interact with environmental regimes, and the ordinary citizens in states. Governance for sustainability requires that we are all clear about the kind of citizenship that is required (Bosselmann, 2008). Any system of Earth governance must emerge from ‘Earth democracy’ which includes global or ecological citizenship (Bosselmann, 2010a). Ecological citizenship describes the normative foundations of governance for sustainability. It ‘poses a new relationship between humans and the natural world and stresses non-reciprocal obligations and responsibilities’ (Bosselmann, 2010a, p. 105; Bosselmann, 2017, p. 227). These kinds of responsibilities are those of stewardship and trusteeship. In the Anthropcene, they amount to Earth trusteeship.

Earth trusteeship reflects the view — held in virtually all religious and cultural traditions — that humans must be stewards and guardians of the land and the natural environment that they belong to. Earth trusteeship involves, however, more than individual moral obligations. It has also legal implications: rights and responsibilities of citizens have corresponding rights and responsibilities of the state. Earth trusteeship functions are therefore not confined to citizens, but include the state acting as a trustee of Earth (Bosselmann, 2017).

Interestingly, international environmental law has increasingly acknowledged such a responsibility of states. Earth trusteeship is the institutionalization of the responsibility of states to protect the integrity of Earth’s ecological systems.

The 1987 Brundtland Report referred to Earth trusteeship and care for the integrity of ecological systems in many passages (Brundtland, 1987). The Preamble of the 1992 Rio Declaration describes the integrity of the global environmental and developmental systems as an overarching goal of states and Article 7 of Rio Declaration postulates: “States shall co-operate in a spirit of global partnership to conserve, protect and restore health and integrity of the Earth’s ecosystem” (Rio Declaration, 1992). The duty of preserving the integrity of ecological systems is expressed in more than 25 international agreements — from the 1982 World Charter for Nature (1982) right through to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement (Kim & Bosselmann, 2015).

16.5.2 A Norm of Ecological Citizenship?

All forces that can influence behaviour are potential tools of governance, thus we must consider normative change. Norms are “standards of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity” (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998, p. 891). They regulate behaviour and constrain actions through peoples’ reference to what is socially acceptable. Norms can be divided into personal norms (a personally perceived obligation) and external norms (societal obligation) (Babcock, 2009). The corresponding consequences of breaking norm behaviour are guilt and shame, respectively. The costs of non-compliance determine the attention and resources that are given to complying with a norm or with ‘soft’ law (Page & Redclift, 2002). An environmental norm could be both personal and external, though arguably the more personally construed the norm, the more compliance will follow (Babcock, 2009).

Despite the scientific evidence and widespread awareness of environmental degradation, levels of consumption and pollution in developed states continue to testify to the dominant notion that economic prosperity is paramount. Babcock (2009) suggests that, in fact, individuals do not make the necessary connection between their economic behaviour and environmental degradation, instead believing that industry is the primary cause of pollution. Babcock rejects regulation as resource intensive, politically untenable, and too at odds with the prevailing norm of privacy and choice (Babcock, 2009, pp. 119–122). The term ‘citizen-consumer distinction’ describes how societies can seem outwardly supportive of environmentalism, yet engage in behaviour that contradicts it (Vandenbergh, 2001). This demonstrates that the environmentalist norm is subservient to other norms (choice, independence) which validate status quo behaviour. Babcock reviews the many complex reasons for this, as well as the difficulties in using norms as an alternative to government coercion, but ultimately advocates in favour of norm change (Babcock, 2009).

In 1998 Finnemore and Sikkink (op.cit.) developed the norm life cycle which explains how norms change over time. The first stage of the cycle is norm emergence, followed by a ‘tipping point’ when the critical mass of people (or states) adopt the norm. The second stage is acceptance, or a ‘norm cascade’, and the third stage is norm internalization when the norm is taken for granted and no longer the subject of public debate, but an automatic dictate of behaviour. If we consider a ‘green norm’ both domestically and internationally, it is highly debateable whether we have progressed beyond stage one. Ingebritsen (2002, p. 15) argues that the sustainable development norm has taken hold and survived the first two phases — finding salience at local, national and regional levels of governance. However, the wider subscription to the latter idea certainly indicates that the principle of sustainability (and its corresponding requirements of radical behavioural changes) has a long way to go in terms of pervading public consciousness. The “good news is that the inescapable reality of human dependence from nature can only be ignored to a point” (Bosselmann, 2010a, p. 104). Perhaps the first step to diffusing a norm in developing states is to bring the reality back to the polluters and reduce the amount that environmental costs can be externalized. This is why ‘the shift from an abstract acceptance of sustainability to actual policies of sustainability is possibly the biggest challenge of our time’ (Bosselmann & Engel, 2010, p. 16).

16.5.3 Participatory Rights

Parallel to the vital project of propagating ecological citizenhip and Earth trusteeship, institutions must be re-designed to ensure that citizens can be heard. Citizens can only be effective vanguards for change to the extent that regimes allow citizens’ participation and provide channels for pressure to be exerted (Bosselmann, 2010b). Hence genuinely democratic systems can be effective conduits for cooperation (Gleditsch & Sverdrup, 2002). The need for procedural and participatory rights of citizens is enshrined in principle 13 of the Earth Charter (2000). International organizations are state-controlled, “elitist, technocratic and undemocratic” (Okereke, 2008, p. 9). Often only limited participatory rights are given to NGO groups.[1] Rights are conferred vertically, so civil society has an important task in insisting that states act as trustees for the environment and this includes allowing the participation of civil society (Bosselmann, 2016, pp. 4, 10, 231). Moreover, to the extent that global civil society is not ‘democratic’ per se, institutions must allow for all voices to be heard, not only western coalitions (Bosselmann, 2010b). Being allowed to contribute to the chorus of global civil society is a privilege not extended to all since it necessitates material resources (technology, multilingual communication) and a large amount of time (Young, 1997; Bosselmann, 2010b). An important part of fortifying a truly ‘global’ civil society, capable of responsive adaptation to competing norms, will be fostering civic plurality and association (Rayner & Malone, 2000).

The relationship between civil society and institutions is one of mutual dependence — civil society organizes the material and ideational resources of institutions, and institutions help to shape behaviour (Wapner, 1997). In order to ensure that institutions do not undermine any grass-roots normative project, civil society members must act as agents for institutional change. This means ensuring that norms reach institutional level. This task requires the inclusion of an overarching ethical value into doggedly formalistic legal systems (Weeramantry, 1997, p. 18). Barresi (2009) suggests an approach called the “mobilization of shame”. He advocates that socialising key groups to new ideas about nature and the implications of sustainability could re-shape and transform legal culture (Barresi, 2009). The normative approach operating at state and corporate level would mean that civil society could “prod states into dramatic policy changes by making any other course of action seem shameful” (Barresi, 2009, p. 30). This is essentially an articulation of sanctions for non-compliance with external norms. The difficult task with state representatives and businesspeople would be ensuring that ecological norms also resonate from within. Unless and until states and corporates are responsible actors and environmental trustees, organizations and institutions are not effective tools of sustainable governance (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 90).

16.6 The Earth Charter: A Framework for Global Governance

The Earth Charter (2000) represents a popular expression of these normative elements at the global level. As an ethical framework the Earth Charter enshrines the code of conduct that is necessary to observe the principle of sustainability (Bosselmann & Engel, 2010). As a declaration which is transnational, cross-cultural and inter-denominational the Earth Charter projects a truly global vision despite different cultural value systems and positions in the political economy (Bosselmann & Taylor, 2005; Okereke, 2008). The Charter has four main themes which form the foundation of a sustainable global society: respect and care for the community of life (principles 1-4); ecological integrity (principles 5-8); social and economic justice (principles 9-12); democracy, non-violence and peace (principles 13-16). The Earth Charter still assumes the legitimacy of state-centric international regimes and international law but asserts that only multilevel cooperation between government, civil society and business can achieve effective governance (Bosselmann, 2008).

The definition of human security that is used in this chapter draws on environmental, social and economic areas. The Earth Charter achieves what the UNDP (1994) definition does not. Human security, as affected by interdependent and indivisible challenges, relies on a categorical imperative that “we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations” (Earth Charter Initiative, 2000, Preamble). The Earth Charter reflects ‘strong’ sustainable development with the three fundamental elements (environment, social welfare and economic welfare) but organises them to reflect the ‘temple of life’ paradigm (see Section 16.3) and the fundamental understanding that ecological integrity is not one of three equally important goals, but the basis of all life (Bosselmann, 2008; Bosselmann, 2010b). Central to environmental and social equity is the concept of common but differentiated responsibility. The Earth Charter does not develop this concept fully, but it will be crucial for human security regimes and global governance that the ethic of responsibility manifests in a way which acknowledges the realities of the international political economy.

An important means of spreading the ecological norm is to publicly declare the intent (Bosselmann, 2008). The Earth Charter is a universal covenant of global responsibilities (Engel, 2007; Bosselmann, 2008). Genuine behavioural change can only be achieved when people commit to their role as an ecological citizen and the responsibilities that ensue. Covenants represent a promise and a deeply felt commitment (Bosselmann, 2008). “A declaration can be a very powerful manifestation of changed awareness and morality” and like other soft law may “be very effective in ‘lifting the game’ and increasing pressure on governments” (Bosselmann, 2008, p. 322; Bosselmann & Engel, 2010, p. 23). In terms of our norm life cycle this could be an important development in the first stage of norm emergence. As more individuals, organizations and states endorse the Earth Charter the norm becomes stronger and more influential. The goal is for the principle of sustainability to overtake three-pillar sustainable development and inform all policy areas including security. We might interpret the Earth Charter and its visionaries as ‘norm entrepreneurs’, and at the very least as fulfilling an educative function that is fundamental to socialization and norm diffusion (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998; Ingebritsen, 2002; Bosselmann & Engel, 2010).

Ultimately we still see the predominance of economic ‘rationality’ in the core rules of environmental regimes despite the ethical and normative aspirations of global civil society (Okereke, 2008). However, in our project of changing the ‘ought’ to the ‘is’, a universal covenant such as the Earth Charter which “represents the most profound and powerful social bond we know” represents a promising platform for future action (Bosselmann, 2008, p. 322).

The Earth Charter is silent as to the techniques and methodologies that we should use to implement ecological governance but it is a useful starting point for a ‘global constitution’ (Bosselmann, 2010b). The Earth Charter already sets the benchmark for human behaviour — that it is just, participatory, sustainable, and peaceful (Earth Charter, 2000, principle 3). A constitution is a higher level of law which sets forth the fundamental rules of a political community (Bodansky, 2009). A global constitution would lay out the dimensions of ecological citizenship with the legal certainty of substantive rules. Other discussion about how best to implement good governance generally fluctuates between evolution and reform of existing governance, and developing entirely new governance structures (Bosselmann, 2016, p. 192). Roch and Perrez (2005) proffer the ‘double c / double e approach’ as key to the success of environmental governance (Roch & Perrez, 2005, p. 18). This refers to coherence (coordination between policies and actors), comprehensiveness (of environmental policy), and efficiency and effectiveness (Roch & Perrez, 2005). Perceptions that the UNEP is ineffective have led to calls for a more centralized environmental body such as a World Environmental Organization, or a Security Council for the Environment (Roch & Perez, 2005). Ultimately, it seems doubtful that we need an overarching global governance structure, but what is crucial is that sustainability be overarching and the common element among a network of governance levels (Bosselmann et al. 2008). We need to be realistic without sacrificing ambition and vision (Roch & Perrez, 2005). We urgently need states to implement measures identified in the Global Ministerial Environment Forum in Cartagena 2002 (Roch & Perrez, 2005). However in the long term, strengthening governance is a dual process of local empowerment, engagement and socialization to ecological citizenship, as well as working to establish the principle of sustainability as a principle of national and international law (Bosselmann et al., 2008). Underlying this process is infusing the principle of sustainability with the tangible authority to affect actual change in the way humans interact with nature. Power, in this sense, will come from its social and legal recognition and implementation.

16.7 Conclusion

Good governance can only be perceived as value-based; in the ecological age those values are primarily ecological. Accountability, transparency and public participation are essential requirements for good governance but they do not suffice to ensure governance for human security. In the 21st century, human security and environmental security are deeply intertwined. Good governance, therefore, needs to adopt an understanding that the human sphere is ultimately dependent on the natural sphere. To capture the ecological realities involved here, good governance must be based on an ethic of care and responsibility for the Earth, best perceived as Earth trusteeship.

The Earth Charter reflects and defines Earth trusteeship. The challenge will be for our communities, for local and national governments, for the entire multi-layered system of governance to spell out what actions it involves and how it must guide us all in our search for human security.

Resources and References

Review

Key Points

- Environmental degradation exacerbates structural violence, which leads to increased social injustice, which further exacerbates poverty and environmental degradation.

- Environmental change acts as a ‘threat multiplier’ because it amplifies scarcities.

- Environmental security is the foundation on which human security stands. It requires adequate provisions for adaptation and prevention so that environmental changes exert less impact on well-being.

- Conventional ‘weak’ notions of ‘sustainable development’ cannot succeed in increasing human security because they do not recognise the primacy of ecological integrity among the requirements. Unfortunately they show no sign of abating in their influence on governance.

- Good environmental governance rests on normative principles and process principles that include all of civil society in the decision-making process.

- Good environmental governance is an essential component of Earth democracy, which also requires profound changes in people’s values.

- The Earth Charter outlines the major values and principles that can lead to a global democratic regime of good environmental governance.

Extension Activities & Further Research

- In Section 16.3 it was argued that economic security should not be regarded as a ‘pillar’ for the principle of sustainability. In your view, does this also apply to the ‘four pillar’ model of human security? What are the arguments for and against that proposition?

- Section 16.4.2 outlines some principles of ‘good governance.’ To what extent does good governance also mean democratic governance?

- An important component of the process of Earth democracy will have to be the disenfranchisement of the bloated corporate power groups who currently dominate decision-making processes at so many levels without any mechanism of accountability. Section 16.5.2 leads to the question, “To what extent can a civil society capable of such good governance also be capitalist?” — the corollary being “to what extent does it have to be?” Any suggestions?

List of Terms

See Glossary for full list of terms and definitions.

- anthropogenic

- Earth Charter

- ecological security

- ideational

- strong sustainability

- Three Pillars of Sustainable Development

- weak sustainability

Suggested Reading

Barnett, J. (2007). Environmental security and peace. Journal of Human Security, 3(1), 4–16. doi.org/10.3316/JHS0301004

Bosselmann, K., & Engel, J. R. (Eds.). (2010). The Earth Charter: A framework for global governance. KIT Publishers.

Earth Charter International. (2000). The Earth Charter. https://earthcharter.org/read-the-earth-charter/

Kaplan, R. D. (1994). The coming anarchy. The Atlantic, 273(2), 44–76. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1994/02/the-coming-anarchy/304670/

Kaplan, R. D. (2000). The coming anarchy: Shattering the dreams of the post cold war. Random House.

Mosquin, T., & Rowe, S. (2004). A manifesto for Earth. Biodiversity 5(1), 3–9. http://www.ecospherics.net/pages/EarthManifesto.pdf

References

Babcock, H. M. (2009). Assuming personal responsibility for improving the environment: Moving toward a new environmental norm. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 33(1), 117–175. https://harvardelr.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2019/07/33.1-Babcock.pdf

Barnett, J. (2007). Environmental security and peace. Journal of Human Security, 3(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.3316/JHS0301004

Barresi, P. A. (2009). The right to an ecologically unimpaired environment as a strategy for achieving environmentally sustainable human societies worldwide. Macquarie Journal of International and Comparative Environmental Law, 6, 3–30.

Bischoff, B. (2010). Sustainability as a legal principle. In K. Bosselmann and J. R. Engel (Eds.), The Earth Charter: A framework for global governance (pp. 167–190). KIT Publishers.

Bodansky, D. (2009). Is there an international environmental constitution? Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 16(2), Article 8. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1402&context=ijgls

Bosselmann, K. (1995). When two worlds collide: Society and ecology. RSVP Publishing.

Bosselmann, K. (2006). Strong and weak sustainable development: Making differences in the design of law. South African Journal of Environmental Law and Policy, 13(1), 39–49. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA10231765_45

Bosselmann, K. (2008). The way forward: Governance for ecological integrity. In L. Westra, K. Bosselmann, & R. Westra (Eds.), Reconciling human existence with ecological integrity (pp. 319–332). Earthscan.

Bosselmann, K. (2010a). Earth democracy: Institutionalizing sustainability and ecological integrity. In J. R. Engel, L. Westra, & K. Bosselmann (Eds.), Democracy, ecological integrity and international law (pp. 91–115). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Bosselmann, K. (2010b). Outlook: The Earth Charter – A model constitution for the world? In K. Bosselmann & J. R. Engel (Eds.), The Earth Charter: A framework for global governance (pp. 239–256). KIT Publishers.

Bosselmann, K. (2013). The concept of sustainable development. In K. Bosselmann, D. Grinlinton, & P. Taylor (Eds), Environmental law for a sustainable society (2nd ed.). New Zealand Centre for Environmental Law.

Bosselmann, K. (2016). The principle of sustainability: Transforming law and governance (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Bosselmann, K. (2017, April 21). The next step: Earth trusteeship [Address to the United Nations General Assembly]. http://files.harmonywithnatureun.org/uploads/upload96.pdf

Bosselmann, K., & Engel, J. R. (Eds.). (2010). The Earth Charter: A framework for global governance. KIT Publishers.

Bosselmann, K., Engel, J. R., & Taylor, P. (2008). Governance for sustainability: Issues, challenges, successes. International Union for Conservation of Nature. https://www.iucn.org/content/governance-sustainability-issues-challenges-successes

Bosselmann, K., & Taylor, P. (2005). The significance of the Earth Charter in international law. In P. B. Corcoran (Ed.), The Earth Charter in action: Toward a sustainable world (pp. 171–173). KIT Publishers. https://earthcharter.org/library/the-earth-charter-in-action-toward-a-sustainable-world-english/

Cherp, A., Antypas, A., Cheterian, V, & Salnykov, M. (2007). Environment and security: Transforming risks into cooperation. The case of Eastern Europe: Belarus – Moldova – Ukraine. United Nations Environment Programme; UN Development Programme; UN Economic Commission for Europe; Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe; Regional Environmental Centre for Central and Eastern Europe; North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/8070/-Environment%20and%20Security_%20Transforming%20risks%20into%20cooperation-20088204.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Council of the European Union; European Commission. (2008). Climate change and international security (No. S113/08). https://op.europa.eu/s/od52

Dalby, S. (2002). Environmental security. University of Minnesota Press.

Detraz, N. A. (2010). The genders of environmental security. In L. Sjoberg (Ed.), Gender and international security: Feminist perspectives (pp. 103–125). Routledge.

The Earth Charter. (n.d). The Earth Charter. https://earthcharter.org/

Elliot, L. (2004). The global politics of the environment (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Engel, J. R. (2007). A covenant of covenants: A federal vision of global governance for the twenty-first century. In C. L. Soskolne (Ed.), Sustaining life on Earth: Environmental and human health through global governance. Lexington Books.

Eriksen, T. H. (2010). Human security and social anthropology. In T. H. Eriksen, E. Bai, & O. Salemink (Eds.), A world of insecurity: Anthropological perspectives on human security (pp. 1–20). Pluto Press.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081898550789

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

Gleditsch, N. P., & Sverdrup, B. O. (2002). Democracy and the environment. In E. A. Page & M Redclift (Eds.), Human security and the environment: International comparisons (pp. 45–69). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hulme, K. (2008). Environmental security: Implications for international law. Yearbook of International Environmental Law, 19(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/yiel/19.1.3

Ingebritsen, C. (2002). Norm entrepreneurs: Scandinavia’s role in world politics. Cooperation and Conflict, 37(11), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836702037001689

International Union for the Conservation of Nature. (2004). IUCN Resolution on the Earth Charter (Res. 3.022). https://earthcharter.org/library/iucn-resolution-on-the-earth-charter/

Kaplan, R. D. (1994). The coming anarchy. The Atlantic, 273(2), 44–76. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1994/02/the-coming-anarchy/304670/

Kim, R. E. & Bosselmann, K. (2015). Operationalizing sustainable development: Ecological integrity as a Grundnorm of international law. Review of European, Comparative and International Environmental Law, 24(2), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12109

Liftin, K. T. (1999). Constructing environmental security and ecological interdependence. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 5(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00503005

Manno, J. P. (2010). Haudenosaunee great law of peace: A model for global environmental governance? In J. R. Engel, L. Westra, & K. Bosselmann (Eds.), Democracy, ecological integrity and international law (pp. 158–170). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Mosquin, T., & Rowe, S. (2004). A manifesto for Earth. Biodiversity, 5(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2004.9712713

Myers, N. (1993). Ultimate security: The environmental basis of political stability. W. W. Norton.

O’Brien, K. L., & Leichenko, R. M. (2000). Double exposure: Assessing the impacts of climate change within the context of economic globalization. Global Environmental Change, 10(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00021-2

OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms 2005. Three-pillar approach to sustainable development. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6591

Okereke, C. (2007). Global justice and neoliberal environmental governance: Ethics, sustainable development and international co-operation. Routledge.

Page, E. A. (2002). Human security and the environment. In E. A. Page & M. Redclift (Eds.), Human security and the environment: International comparisons (pp. 27–44). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Rayner, S., & Malone, E. L. (2000). Security, governance, and the environment. In M. R. Lowi & B. R. Shaw (Eds.), Environment and security: Discourses and practices (pp. 49–65). Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9780312224851

Roch, P., & Perrez, F. X. (2005). International environmental governance: The strive towards a comprehensive, coherent, effective and efficient international environmental regime. Colorado Journal of Environmental Law and Policy, 16(1), 2–25.

Shani, G. (2007). Introduction: Protecting human security in a post 9/11 world. In G. Shani, M. Sato, & M. K. Pasha (Eds.), Protecting human security in a post 9/11 world: Critical and global insights (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230592520_1

Tadjbakhsh, S., & Chenoy, A. M. (2006). Human security: Concepts and implications. Routledge.

United Nations. (1982). World Charter for Nature (UN Doc. A/37/7). https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/37/7

UN. (1992). Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development – Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (UN Doc. A/Conf.151/26 [Vol. 1]). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1709riodeclarationeng.pdf

UN. (1992). Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/doc/ref/rio-declaration.shtml

UN. (2002). Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development. In Report of the world summit on sustainable development (pp. 1–5, UN Doc. A/Conf.199/20). https://undocs.org/en/A/CONF.199/20

UN Development Programme. (1994). Human development report 1994: New dimensions of human security. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-1994

Vandenbergh, M. P. (2001). The social meaning of environmental command and control. Virginia Environmental Law Journal, 20, 191–219. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/1022/

Vandenbergh, M. P. (2004). From smokestack to SUV: The individual as regulated entity in the new era of environmental law. Vanderbilt Law Review, 57(2), 515–628. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/1029/

Voigt, C. (2008). Sustainable security. Yearbook of International Environmental Law, 19(1), 163–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/yiel/19.1.163

Wapner, P. (1997). Governance in global civil society. In O. R. Young (Ed.), Global governance: Drawing insights from the environmental experience (pp. 65–84). MIT Press.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future (UN Doc. A/42/427). http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm

Weale, A., Pridham, G., Cini, M., Konstadakopulos, D., Porter, M., & Flynn, B. (2000). Environmental governance in Europe: An ever closer ecological union? Oxford University Press.

Weeramantry, C. G. (1997). Separate opinion of Vice President Weeramantry concerning the Gabçikovo-Nagmaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia) [1997 ICJ; 37 ILM 162 (1998)]. https://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/92/092-19970925-JUD-01-03-EN.pdf

Young, O. R. (1997). Rights, rules, and resources in world affairs. In O. R. Young (Ed.), Global governance: Drawing insights from the environmental experience (pp. 1–23). MIT Press.

Long Descriptions

Figure 16.1 long description: A diagram that aims to demonstrate the complexity and interconnectedness of global problems. This diagram has been turned into an ordered list to allow for self-exploration.

A system of self-assertive values of expansion, competition, oppression, and exploitation lead to uncontrolled growth (see #1), poverty in the so-called Third World (see #2), and a feeling of threat (see #4a).

- Uncontrolled growth leads to

- Unbalanced town planning and increasing traffic, which leads to a growing consumption of energy (see #4) and pollution (see #5).

- Industrial production, which leads to pollution (see #5) and waste and pesticides that contaminate soil and water and cause diseases.

- Poverty in the Third World leads to

- Poor health care and illiteracy, which results in poor family planning and population growth (see #3).

- Population growth leads to

- A growing consumption of energy (see #4).

- Excessive agriculture, which leads to the clearing of woodlands, which in turn leads to soil erosion and loss of species and forests dying.

- A scarcity of provisions.

- Over-pasturing, which leads to deserts and a decrease in food production (see #6) as well as soil erosion.

- Growing consumption of energy, which is

- Caused by increasing traffic, population growth, and high military expenses due to the nuclear arms race, which both feeds into and is compelled by a feeling of threat.

- Related to the use of non-renewable energy sources, i.e., fossil fuels like coal and oil, which contribute to pollution, CO2 emissions (see #4d), and regional conflicts.

- Related to the use of nuclear energy, which leads to nuclear waste.

- Related to an increase in CO2, which is partially caused by the clearing of woodlands and contributes to acid rain.

- Pollution, which is

- Caused by increasing traffic, use of fossil fuels, and industrial production.

- Responsible for smog, which causes diseases.

- Responsible for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that deplete the ozone layer and increase UV radiation, which can cause skin cancer and decrease food production (see #6).

- Responsible for greenhouse gases, which have a greenhouse effect that causes changes in the climate and a rise in sea level, which in turn result in changed rainfall patterns and a loss of usable land, all of which lead to a decrease in food production (see #6).

- Decrease in food production, which is

- Caused by deserts due to over-pasturing, changed rainfall patterns, loss of usable land, and an increase in UV radiation.

- A precursor to malnutrition and starvation.

Media Attributions

- Figure 16.1 © 1995 Klaus Bosselmann is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- The Global Forum at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit is a case in point. It was comprised of the NGOs that were not permitted to attend the Summit alongside State representatives. ↵

An ethical framework for building a just, sustainable and peaceful global society in the 21st century; it seeks to inspire in all people a new sense of global interdependence and shared responsibility for the well-being of the whole human family, the greater community of life and future generations (Chapter 16).

Caused by the actions, policies or decisions of humans (Chapter 11, Chapter 16).

Securing the integrity of ecological support structures (ecosystems and the ‘services’ they supply) for the purpose of supporting the ecological pillar of human security (Chapter 16).

This model proposes that sustainability rests on the three pillars of economic, social and environmental sustainability. It implies that the three are equal in their strength and significance, which misrepresents the precepts of basic ecology (Chapter 16).

Based on the concentric spheres model of social systems being nested within the biosphere, it proposes that social and economic activities are absolutely dependent on sustained support from ecosystem services (Chapter 16).

Based on the concentric spheres model of social systems being nested within the biosphere, it proposes that gains in economic capital can compensate for declines in natural capital (Chapter 16).

Consisting of or relating to ideas (Chapter 16).