8 Political Hybridity and Human Security in Post-colonial and Post-conflict State Building / Rebuilding

Learning Outcomes & Big Ideas

By the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

- Critique how the literature conceptualises fragile post-colonial states.

- Understand how colonialism fractured indigenous sources of legitimacy and did not replace these with meaningful systems that made sense to local peoples.

- Think about what hybrid political institutions might look like, using case examples.

- Locate the arguments for and against the hybrid approach in the context of the human security debate.

Big ideas gained from this chapter include:

- Political hybridity is a combination of modern and customary-traditional norms, values and institutions, as well as international regimes.

- Fragile states are characterized by a sovereignty gap that results in large portions of the population remaining insecure, ungoverned, and ungovernable.

- In some regions with fragile states human security is best ensured through hybrid political systems.

- An important component of sustainable development is ensuring that governing structures are considered legitimate by the governed.

- Many developing countries are hampered by limitations in the capacity, the effectiveness, and the legitimacy of the state.

- In those cases, rational legal sources of power and authority should be balanced by traditional sources in order to maximise human security.

Summary

One of the cornerstones of development aid to developing countries consists of efforts to strengthen central government authority. These efforts are not often as successful as their designers envision. Apart from structural explanations, the reasons lie in the lack of legitimacy that compromises the ability of state authorities to govern outlying areas. Legitimacy is lacking in the eyes of the populace because the central state authority is usually modelled after the Western Weberian pattern and thus foreign to many cultures, whereas traditional sources of authority and customary norms receive much greater respect. The result is often a fragile state in danger of ‘failing’ and poor human security. The most promising way to mitigate this situation is to aim for a ‘hybrid’ approach to governance that makes use of both sources of authority.

Chapter Overview

8.2 Enhancing State Resilience and Promoting Human Security

8.3 The Quest for Human Security in Insecure and Fragile States

8.4 Diagnosing Vulnerability and Preventing State Failure

8.5 Promoting Human Security in Weak States

8.7 Community Sources of Legitimacy

Extension Activities & Further Research

8.1 Introduction

The international donor community has committed itself to assist in “building effective, legitimate and resilient state institutions, capable of engaging productively with their people to promote sustained development” and human security (OECD-DAC, 2007, Preamble). The Paris Declaration of March 2005 in particular addresses the need to deliver effective aid in fragile states and declares as the “long-term vision for international engagement in fragile states (…) to build legitimate, effective and resilient state and other country institutions” (OECD, 2005, point 37).[1] State-building is seen by major donors as a central dimension of development assistance, and functioning, effective and legitimate state and society institutions are seen as a prerequisite for sustainable development.

In this context, practical policies and assistance have very much focussed on capacity and institution-building as a means for generating political effectiveness. In comparison, legitimacy, which many would argue is a prerequisite for capacity and effectiveness has been relegated to a somewhat secondary position. The underlying assumption is that legitimacy somehow automatically result from effectiveness. Only recently, have issues of legitimacy gained more prominence in their own right. Importantly, the OECD-DAC’s Fragile States Group State Building Task Team has given legitimacy prominence in its deliberations and initial findings on state-building. This provides an excellent starting point for further conceptual and practical work on this topic in the context of the necessities of state formation under conditions of fragility.

My proposition in this chapter is that external actors working in fragile post-colonial environments need to focus much more attention on legitimacy issues than has been the case so far and to do so they have to widen their understanding of legitimacy considerably. The hypothesis underlying this paper, is that legal-rational legitimacy as found in the developed Western OECD states is only one type of legitimacy applicable to fragile states and situations, and it is important to engage with other types of legitimacy in order to help build effective, resilient and sustainable states in fragile situations. The chapter argues that it is important to blend/hybridise rational legal sources of legitimacy with traditional and charismatic legitimacy, and the processes and the contexts that constitute their sources. This is the only way of ensuring higher levels of support for state institutions and is critical to the promotion of human security. In fragile situations traditional (and to a lesser extent, charismatic) legitimacy matter and have to be taken into account in state-building endeavours in relation to state formation, peace-building and development. This is not to say that this is an easy task, quite the contrary. It is extraordinarily challenging to understand exactly what legitimacy is in fragile situations and even more difficult to design internal and external intervention strategies capable of generating higher levels of political legitimacy that support state-building, peace-building and development. It is complicated because there is often confusion about the different types of legitimacy and their relation and interaction, and about what legitimacy resides in the state as a set of legislative, executive and judicial institutions and what legitimacy resides in particular governments or regimes. They are mutually reinforcing. Legitimate state institutions are conducive to the emergence of legitimate regimes and governments and vice versa. But sometimes there are odious regimes in legitimate states and states which lack legitimacy hosting quite positive regimes. My focus is on the legitimacy of state institutions and their interaction with non-state societal institutions and actors who enjoy legitimacy, not on the legitimacy of specific governments or regimes. In the context of state-building in fragile situations in the developing world, it is the institutions of states that are modelled along the Western Weberian template (which is the OECD model state) that have legitimacy problems; it is the state institutions as such, and not only specific governments, that have had to struggle with the lack of legitimacy.

8.2 Enhancing State Resilience and Promoting Human Security

The problem of how to build or rebuild state systems continues to challenge bilateral, regional and multilateral development agencies in most parts of the world. State systems should:

- Do ‘justice’ to indigenous cultures

- Facilitate high levels of ‘democratic’ participation

- Ensure effective delivery of government services

- Have high levels of grounded legitimacy.

Much insecurity is generated by political systems threatening indigenous peoples and marginalized groups, acting oppressively and corruptly and not having either the will or resources to deliver effective, capable and legitimate governance.

The dilemma is how ‘stable and well established democracies’ can work with less democratic regimes in order to build capable, effective, legitimate and relatively uncorrupt state institutions in situations of poverty, inequality, corruption and structural instability. Frank Fukuyama framed the problem as follows, “Can informal institutions embedded within social norms [or ‘hybrid institutions’] be made to work more effectively for development outcomes in the absence of a functioning Weberian state system?” [2]

It is probably more useful, for both analytical and policy purposes, to direct Fukuyama’s question to focus attention on whether new kinds of ‘hybrid’ political institutions can evolve that will combine the comparative advantages of both the classic Weberian system and traditional or customary institutions.

In most countries in Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia, for example, the modern OECD model of the state has not evolved as predicted and what state institutions exist are largely incapable of meeting the specific political, economic and social needs of different countries and cultures within the region. Similarly, customary and traditional forms of order have been challenged and in many cases severely undermined by colonial rule and market capitalism and have often been usurped by individuals and groups for specific partisan interest rather than the common good of a village, community or province.

8.3 The Quest for Human Security in Insecure and Fragile States

In many if not most post-colonial states, individual security is neither guaranteed by the state nor by traditional mechanisms and individuals, and groups find themselves caught between tradition and modernity without conventions or institutions to guide appropriate economic, political or social behaviour with kin groups shouldering most responsibility for the care and security of members. The challenge facing analysts and policy makers, therefore, is how to think about this problem in non-dualistic ways so that the Weberian State does not trump traditional order or vice versa. In other words how can we think about this problem in a way that combines the strengths of both modern and customary systems in a new form of political organisation? The particular challenge of this is how to do this without wittingly or unwittingly reinforcing patrimonial/neo-patrimonial systems that are often corrupt and predatory.

Socio-cultural evolutionary theorists such as Ferdinand Toennies (1957), Max Weber (1949) and Talcott Parsons (1966), proposed that change processes are irresistible and universal. Modern evolutionary theory argues that societies move in a more or less linear direction from traditional to modern forms of economic, social and political forms of organization. In the process of evolution, state institutions become differentiated and acquire a measure of autonomy from traditional economic and social systems. In Max Weber’s view, the mark of a ‘developed’ state is that it has separate administrative, representative and executive capacities and has a ‘monopoly of coercive force’ so that it is able to control the territory under its sovereign jurisdiction. At minimum, states should be able to counter any resistance to legitimate authority and (more optimally) provide basic services in order to ‘win’ popular legitimacy. In this evolutionary process from traditional to modern, it is assumed that modernity will trump tradition. It will do so because market forces and industrialization will generate irresistible dynamics in favor of possessive individualism justified by ideologies or myths such as consumer sovereignty in the economy and citizen sovereignty in the polity. What evolutionary theory seems to have ignored, however, is the strength, resilience and persistence of custom and tradition both as a source of identity and as a means of organizing social, economic and political systems in a modern, globalised world system. Persistent and intractable conflicts in Africa, for example, often take place in post-colonial states where little or no effort has been made to attend to locality, customs or traditions with the result that political institutions sit uncomfortably in relation to traditional economic, social and religious orders. They are ineffective in terms of the delivery of services, lack any organic connection to locality and have difficulty ruling by persuasion. They thus tend to revert to colonial methods, dominating by divide and rule and by specific processes of inclusion and exclusion.

National and global capitalism, despite its dominance, has not succeeded in trumping all traditional economies and representative democratic institutions have not completely replaced customary or traditional rules and rulers. On the contrary there has been a ‘radical’ reassertion of tradition and the importance of a relatively undifferentiated approach to social, economic and political organization in a variety of high and low context cultures.[3] This can be viewed both positively and negatively. The articulation of tradition and custom can generate a strong sense of continuity, trust, and order in complex social systems. Negatively, tradition can also be used as a justification for practices which are patrimonial, reactionary and unjust for groups such as women and youth. Custom is sometimes used to justify patriarchy and patterns of domestic violence, for example, and also to negate the positive contribution of youth in cultures which venerate age. The challenge confronting development specialists, policy makers and agents of change, therefore, is how to work with traditional ‘authority’ to reinforce its progressive role and to diminish its more negative influence. This is particularly important in relation to the role of the state in promoting human security. How can states do this without a deep acknowledgement of the long continuities that exist in every social system and without some effort to give these customs a place in new state formations or their reformation in the wake of conflict?

8.4 Diagnosing Vulnerability and Preventing State Failure

Nowhere is this more important than in relation to the development of appropriate mechanisms for ensuring the security of individuals and groups, of appropriate forms of ‘community governance’ and of effective machinery for the peaceful settlement of individual and collective grievances. These issues are normally assumed to be the preserve of the State (at both local and national government levels). In many conflict zones, however, state systems fail in their duty of care and are a primary source of insecurity for citizens. They are incapable of delivering security, order, predictability and essential services such as education and health. Far from creating environments, therefore, within which robust markets can emerge, the state system is often a primary source of predation and an impediment to economic growth or what might be called ‘affluent subsistence.’

This has given rise to the ‘Fragile, Failed and Failing State’ literature which focuses attention on the problems that generate failed and failing states, e.g rampant corruption, predatory elites, an absence of the rule of law and severe ethnic and religious divisions. The fragile state literature argues that there will be no development without security and there will be no security without strong and legitimate state systems capable of imposing their will on potentially recalcitrant citizens (Foreign Policy and Fund for Peace, 2007).

The solution to vulnerability, therefore, is often seen as the development of an effective military, police and penal capacity as the first and most pressing imperative confronting modern state systems. The Failed and Failing State perspective has been quite influential with policy makers in the last five years with the result that much attention has been dedicated to enhancing state effectiveness (normally seen in terms of the state’s monopoly of force and coercive capacity) so that state systems can dominate and control their populations and territory, in order to reduce their vulnerability to and capacity to do violence to each other.

While the diagnosis might be correct, the prescriptions thus far have not been particularly successful and in some instances have enhanced the repressive capacities of the state without increasing the security of citizens. These initiatives have by and large reasserted the centrality of a strong state system based on classic ‘Westphalian principles’ in the absence of either the historic, economic or geographical conditions that make such systems possible. They have emphasised respect for the sovereign equality of nation states externally without, in many instances, a corresponding respect for the dignity and basic rights of all people within the state. A good case could be made that much of this literature has focused too much attention on state entitlements without paying the same attention to state responsibilities both internally and externally.

Ashraf Ghani and others (2005) have responded to some of these criticisms in their analysis of what they call the sovereignty gap. This refers to the incapacity of many states in the developing world to protect citizens and to extend basic services to the whole population. Ghani et al, reiterate the mantra that most developing states have limited internal accountability and responsibility and do not possess a monopoly of force. Their solutions, however, still direct most attention toward the approach of enhancing ‘good’ governance and the central functions of the state in the hope that this will generate the conditions within which development can take place. ‘Trickle down’ will only occur once development assistance has ‘trickled up’ to reinforce central state functions! They propose that the underlying concept of the State remains some variation on the European OECD model, without much practical appreciation of other non-state sources of order, stability and development. In fact it is somewhat surprising how little of this literature considers state-civil society relationships and more surprising still how almost no-one considers the relationships between state systems, civil society and customary orders. It is simply assumed that if state systems can be made capable, effective and legitimate they will fulfill something akin to the traditional Weberian functions of the state.

The challenge facing policy makers is not so much the goals of state capability, effectiveness and legitimacy as what constitutes appropriate means to achieve these ends. My argument here is that until customary norms, values and institutions are taken seriously and incorporated directly into state building dynamics and vice versa these goals will remain elusive.

OECD style states are in the minority rather than a majority within the United Nations. Most states in developing parts of the world, and particularly within much of Africa and in Oceania represent what can be called hybrid political orders. The locus of much social order and effective governance in these states resides in non-state forms of customary rule rather than in government institutions. This does not mean that these states should be regarded as ‘incomplete,’ or ‘not yet’ properly built, or ‘already’ failed. Rather than thinking in terms of fragile states, it is theoretically more appropriate and practically more fruitful to think in terms of hybrid political orders. Instead of assuming that the complete adoption of western state models is the most appropriate avenue for conflict prevention, security, development and good governance, therefore, it might be more appropriate to focus on models of governance which draw on the strengths of social order and resilience embedded in community life. Without wishing to idealise custom and tradition I hypothesize that this hybrid model holds particularly true for societies in Africa and the Pacific. Hybrid models which genuinely blend or combine traditional and modern norms and practices are more likely to deliver effective, functioning and legitimate governance precisely because they build on the hybridity and multiplicities of existing political orders. This is not to imply that they will always or consistently generate such governance. It is possible for hybrid political orders to generate insecurity, be predatory and patrimonial as well, in which case hybrid forms will have negative rather than positive consequences. In the main, however, I would argue that hybrid models—in post-colonial environments—have a better chance of generating capable and effective governance than non-hybrid models.

8.5 Promoting Human Security in Weak States

The current political and scholarly debate about state fragility and state-building frames the issues at stake too narrowly. It sometimes sees only the problems (real though they are) without also taking into account the strengths of the societies in question, acknowledging their resilience and encouraging indigenous creative responses to the problems and strengthening their own capacities for endurance.[4]

Talking about ‘weak’ states, for example, implies that there are other actors on the domestic socio-political stage that are strong in relation to the state. In the countries of the Pacific ‘The state’ is only one actor among others, the state order is only one of a number of orders claiming to provide security, frameworks for conflict regulation and social services. In Melanesia, neither colonial rulers nor post-colonial governments have been capable of establishing a legitimate state monopoly of violence in the territories that became independent ‘nation states.’ In particular they have not been able to impose effective control over the peripheral outlying areas of their own state territory. There is a considerable sovereignty gap in these systems. Effective control cannot be exerted over the whole state and services cannot be provided by central state institutions. Although state institutions claim authority within the boundaries of a given ‘state territory’, only ‘outposts’ of ‘the state’ can be found in large parts of that very territory. It is a societal environment that is to a large extent ‘stateless.’ ‘The state’ has not (yet) permeated the whole of society.

Having no state institutions, however, does not mean no institutions at all. Rather, traditional non-state societal institutions are of major importance. Traditional societal structures—extended families, clans, religious brotherhoods, village communities—and traditional authorities such as village elders, headmen, clan chiefs, healers, religious leaders (and the belief structures they stand for), etc. determine the everyday social reality of large parts of the population in developing countries even today, particularly in remote peripheral areas. Legitimacy rests with these actors, and not with state institutions – and this lack of formal political legitimacy is a decisive feature of a state’s fragility. Thus state fragility is not only a problem of political will, functions, institutions and powers of enforcement and implementation, but also a problem of preferences, perceptions and indigenous legitimacy.

State fragility, therefore, has two sides: fragility with regard to functions and effectiveness, and fragility of legitimacy. People on the ground do not perceive themselves as ‘citizens of the state’ (at least not in the first place). They identify themselves instead as members of some sub-or trans-national, non-state societal entity (kin group, tribe, village). For them it is the community that provides the nexus of order, security and social safety, not the state.

This has extraordinary consequences for their loyalty or disloyalty to the state. People are loyal to ‘their’ group (whatever that may be); legitimacy and authority rests with the leaders of that group, not with the state authorities. ‘The state’ is perceived as an alien external force, ‘far away’ not only physically (in the capital city), but also mentally. This of course significantly reduces the capacity of state institutions to fulfil core state functions effectively. [5]

The fragile states discourse with its focus on a functioning and effective state organisation is in danger of missing a critical point: the relative disengagement of the people on the ground from the introduced state.[6]

We are seeing in countries as diverse as Aotearoa/New Zealand, Australia and most of Melanesia and Polynesia that traditional actors and institutions, customary law and indigenous knowledge have shown considerable resilience and in many places are enjoying a resurgence that defies ‘modernisation’ theory. It is the indigenous actors and institutions that provide what order there is in the peripheral territories of each state. They form an integral and important dimension of local governance – all the more so as the state’s ‘outposts’ are mediated by ‘informal’ indigenous societal institutions that implement their own logic and their own rules within the (incomplete) state structures.

The infiltration of the outposts of the state distracts them from the ideal type of ‘proper’ state institutions; for example, clientelistic networks penetrate state institutions, and kinship ties determine who is in charge and how the outposts actually operate. State institutions are captured by social forces who make use of them not in the interest of the state and its citizenry, but in the interest of traditional kinship-based entities. This has caused complaints about clientelism and nepotism (wantokism in the Melanesian context), parochialism, corruption and inefficiency with regard to state authorities and the public service (e.g. Turnbull 2002). On the other hand, the intrusion of state agencies impacts on the local societal orders as well. Customary systems of power and rule are subjected to deconstruction and re-formation as they are incorporated into modern state structures and processes.

An additional important dimension of societal and political life in fragile states is the emergence and growing importance of new non-state institutions, movements and formations. This is a consequence of poor state performance, and their activities contribute to the further weakening of state structures. In situations where state agencies are incapable of or unwilling to deliver security and other basic services, people not only rely on their traditional societal structures, but also increasingly turn to other social entities for support since those are perceived as more powerful and effective: warlords and their militias in outlying regions, gang leaders in townships and squatter settlements, ethnically based protection rackets, millenarian religious movements, transnational networks of extended family relations or organized crime, new forms of tribalism — but also NGOs, collectives, and other elements of civil society and local or global social movements. These new formations often are linked to traditional societal entities and try to instrumentalise them for their own goals (power, profit, etc.).

Finally, developments at the international level, induced by the various aspects of globalisation, also put pressure on the state in its conventional form as a nation-state. The state-building approach hence is not only at odds with local traditional forms of social and political order in the Pacific and other regions of the Global South, but it also has to cope with the fact that certain functions of the state are challenged by international developments such as the evolution of international regimes, the emergence of an international civil society, the growing importance of a global capitalist economy, the World Trade Organization and other international organisations.

Regions of fragile statehood thus are places in which diverse and competing claims to power and logics of order and behaviour co-exist, overlap and intertwine: the logic of the ‘formal’ state, the logic of traditional, informal societal order, and the logic of globalisation and international civil society as well as societal fragmentation in various forms (ethnic, tribal, religious). Thus what we call hybrid political orders combine elements of the introduced western model and elements stemming from the local autochthonous traditions of governance and politics.

8.6 Hybrid Political Orders

Hybrid political orders differ considerably from the modern Western model state. Governance is carried out by a collection of local, national and international actors and agencies. In this environment, state institutions are dependent on the other actors – and at the same time restricted by them. Hybrid political orders can also be perceived as or can become ‘emerging states.’ Prudent policies could assist the emergence of new types of states – drawing on the western state model, but acknowledging and working with the hybridity of particular political orders. This might be of particular significance in the Pacific Islands, where small populations and narrow economic bases can weaken the potential for generating state revenue. Attempts at state-building, therefore, which ignore or fight hybridity are likely to experience considerable difficulty in generating functioning, effective and legitimate systems.

Recognising the hybridity of political order should be the starting point for any endeavours that aim at conflict prevention, development and security. One has to search for ways and means of constructive interaction and positive mutual accommodation of modern state and traditional, local, as well as civil society mechanisms and institutions. A central question is how to articulate formal state-based institutions, informal traditional institutions and civil society institutions so that new forms of statehood emerge which are more capable and effective in local circumstances than strictly Western models of the state.

Pursuing such an approach means stressing the positive potential rather than the negative features of the current situation: not to stress weakness, fragility, failure and collapse, but hybridity, generative processes, innovative adaptation, opportunity and ingenuity. This also means treating community resilience and customary institutions as assets that can be drawn upon in order to forge constructive relationships between communities and governments, between customary and introduced political and social institutions. An approach to state-building that takes account of and supports the constructive potential of local community, including customary mechanisms where relevant, is a necessary complement to strengthening central state functions and the political will of state representatives. The main problem is not the fragility of state institutions as such, but the lack of constructive linkages between the institutions of the state and society. The organic rootedness of the state in society is decisive for its strength and effectiveness. Hence engaging with communities in relation to governance and human security is as important as working with governments and central state institutions on the same issues.

Given the importance of legitimacy for state stability or fragility, the development of a sense of citizenship is an essential component of state-building, at least as important as functioning and effective state capacities.[7] Institutions of governance can only be effective and legitimate if the people have a sense of ownership and accountability. Citizenship and the interface between state and society, rather than only the quality of state institutions in themselves are therefore critically important to enhancing state function in emerging states. Unfortunately, building concepts of citizenship that can be understood in traditional environments has so far received much less support than building central government institutions.

There are often real frictions between people’s customary identity as members of traditional communities and their identity as citizens of modern (nation-) states and society. Nevertheless, a broadly constructive interaction of these identities is essential for building citizenship and state under conditions of hybrid political order. Engagement with, not rejection of, customary community-based identities is a necessary part of citizenship formation.

8.7 Community Sources of Legitimacy

It is important, therefore, that agencies working on enhancing state effectiveness should not just focus on the core functions of the state but also on the fundamental ‘community’ sources of legitimacy as well. State functions are not an end in themselves, but a means to provide citizens with development, internal and external peace and human security. Under conditions of political hybridity these goals may be better served by supporting positive mutual accommodation than by concentrating solely on the institutions of the state. The relationship between state institutions and other sources of social order may be constructive, but it might also be destructive or neutral. The challenge is to find ways of supporting constructive interaction. In order to assess the potential for new types of exchange between state and society it is useful to address three core dimensions of the relationship between the state and the other elements of hybrid political orders, namely:

- Substitution: That is, the identification of functional equivalents of the state outside state institutions. The relation between these functional equivalents and state functions needs more thorough investigation which might lead to the next category, namely,

- Complementarity: The identification of areas of overlap between modern state approaches and customary approaches; this will lead to the investigation of potential for or actual articulation with state institutions; and finally

- Incompatibility: The identification of customary approaches that conflict with modern state approaches.

Assessing core state functions in the light of the three dimensions of substitution, complementarity and incompatibility facilitates a richer and more realistic analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of different states. It underpins a broader understanding of what a functioning and effective state might look like and also helps identify ways to support the emergence of such states.

The development of more fully legitimate state processes grounded in community life will necessitate a sophisticated, ongoing, flexible process of exchange between the local-endogenous and the introduced-exogenous systems. There is no guarantee that this process of exchange will always be successful and it is an open question whether societal and political life in the so-called fragile states can sustain this – not least depending on the political will of the main actors. In any event, what we discovered in work done in Bougainville, the Solomons, Timor Leste, Tonga and Vanuatu, was that societies in the Pacific region have – compared to other regions in the Global South—specific advantages that give reasons for optimism.

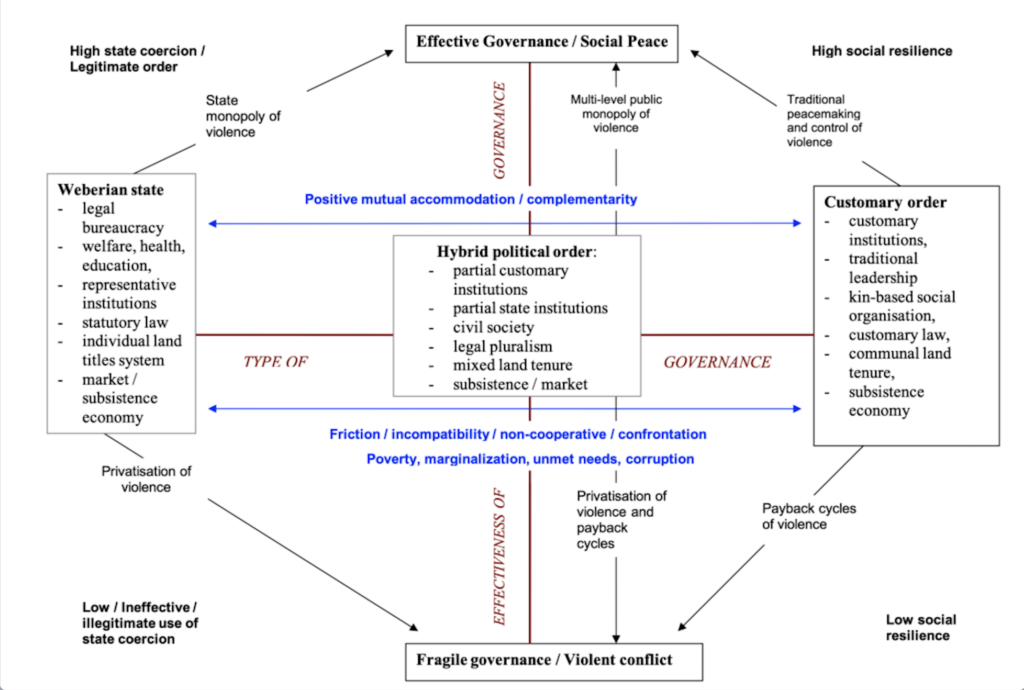

To summarize: functioning and effective statehood means that internal and external actors need to focus as much attention on the dimensions of legitimacy and citizenship as they do on strengthening the core functions of the state. It is our contention, based on working in Vanuatu, the Solomons and Timor Leste, that building new forms of state and citizenship that are based on a positive mutual accommodation between the Weberian State and Customary Order will transform hybrid political orders into emerging states that — in the long run — will generate new forms of governance beyond the model western state. Thus in addition to enhancing the state through reinforcing its core functions, a model of governance that is more sensitive to the multi-stranded character of political order in the Pacific will produce more realistic assessments of social and political resilience and the potential for serious violent conflict. In order to develop this new thinking it is important to communicate it through schematic representation of the model, encompassing ideal types and realistic possibilities. The schema represented in Figure 8.1 highlights how political leadership, political responsibility and new concepts of citizenship might be able to generate higher levels of accountability, legitimacy and effectiveness. It does this by focussing attention on ways that generate a more intentional blend between traditional and modern forms of governance – with neither having either a theoretical or practical primacy. By applying the concepts of substitution, complementarity and incompatibility it should be possible to begin mapping where the Weberian state and traditional conventions and institutions have a comparative advantage. Where no obvious advantage can be identified a case can be made for developing hybrid forms that build on the strengths of both systems. In all of this, the aim is to build on the strengths of community, to highlight how kin and other relationships can be made resilient and adaptable and how security might be guaranteed by both traditional and modern institutions. Policy makers need to ensure that the Weberian model possesses a legitimate monopoly of violence and that communities are able to generate high degrees of social resilience. This is best achieved by attending to the positive features of the spheres of state, civil society and customary rule.

8.8 Centrality of Context

The pursuit of positive synergies between modern and traditional orders (although this is a problematic dichotomy because of the bias towards modernism) always takes place within specific economic and socio-cultural environments. In most parts of Polynesia and Melanesia, for example, the economic environments are stressed by high levels of poverty, hardship and inequality. They are also biased towards urban rather than rural areas. The schema presented above is aimed at developing some research hypotheses on factors that advance or impede functioning, effective and legitimate political order. This schema is a heuristic device and should not be reified.

In this schema there are three ideal types of political order and governance, namely the ideal type of the Weberian state on the one pole and the ideal type of non-state customary order on the other pole, with hybrid political order in between the two. The Western OECD states come closest to the Weberian state in reality, while traditional Melanesian and Polynesian societies were forms of customary order (this type, however, can hardly be found in pure form in today’s world any more). In the Pacific region as well as in other parts of the Global South the hybrid type of political order dominates; it combines elements of both the Weberian and the customary ideal type but normally in an unintentional and ad hoc fashion.

The three types can provide pathways to effective and legitimate governance and hence social peace, and all three types are susceptible to fragility or even collapse and violent conflict. Hybrid political orders, however, seem to be particularly vulnerable. The co-existence of state and customary institutions can be non-cooperative, incompatible or even confrontational and hence lead to frictions that cause fragility, failure and collapse.

Given the ubiquity of hybrid political orders in the Pacific and the Global South the challenge therefore, is to take hybridity as a starting point for endeavours of state-building by means of positive mutual accommodation of state and customary institutions. This might lead to the emergence of new forms of the state that do not simply emulate the western Weberian model but reflect high context cultures, strong social relationships, high social resilience and effective and legitimate political institutions. Hybrid political orders need to be analysed and dissected in order to identify the dynamics that strengthen resilience and diminish fragility.

In order to do so it is useful to focus on the actors and institutions of the hybrid political order and ask who is doing what and how effective their efforts are. In this way it should be possible to develop a political map that will generate a more self-conscious division of labour between the state, civil society and custom. Some of the questions that need to be addressed include who is performing crucial tasks, who is:

- Providing internal (and external) security

- Organising the legal system(s), rule of law

- Providing basic social services

- Organising political representation and decision-making

- Organising leadership

- Generating political will and commitment of leaders

- Included and who is excluded in socio-political networks

- Organising accountability

- Claiming legitimacy, and on what basis

- Defining citizenship/social belonging, and on what basis

- Perceiving the institutions of political order, and in what ways

- Organising economic activities, gaining and providing access to and distributing resources

- Allocating and managing revenues for the fulfilment of political tasks

- Organising personnel for the fulfilment of political tasks.

These factors can then be analysed and rated according to their contribution to an effective and legitimate form of governance (or the lack thereof). Following this methodology will, for example, show which (combination of) institutions and actors actually provide internal security: Is it an institution of the state (the police) or a customary non-state institution (the elders)—or both? And what is the relation between the two—complementarity, substitution or incompatibility?

The rating then will indicate how effectively or ineffectively the function is fulfilled. The overall assessment of the sum of the factors will finally allow a positioning of the given political order in the diagram along the axes of the type of governance and the effectiveness of governance. This allows for a comparison of various countries. On the basis of such an analysis and comparison a reassessment and eventually a revision of the current analytical approaches as well as the current state-building approaches can be conducted.

In this context it is again useful to focus on Pacific Island states and societies. Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Bougainville, the Solomon Islands and Tonga for example all provide different illustrations of hybridity in action. Over the past thirty years Vanuatu has been spared violent conflict and a disruption of state functions on a larger scale. However, there is considerable conflict potential that could lead to conflict escalation. Hence one might perceive the situation in Vanuatu as pre-conflict, with conflict prevention and state-building an urgent task. On the other hand, kastom—the traditional social, cultural and political order—is still very strong in Vanuatu and very much determines the everyday life of the majority of Ni-Vanuatu people. The country is in a critical stage of its history as an emerging state, and the prospects for development, security and peace very much hinge on the establishment of functioning, effective and legitimate forms of governance.

The situation in Papua New Guinea is highly volatile, particularly in view of recent political instability. The country has to struggle with its immense diversity and the stark differences in life-worlds within its boundaries. Both the political elite and the ordinary ‘citizens’ are confronted with the challenges of harmonising customary ways of life and the needs and opportunities of modern society in an era of rapid change and globalisation. Violence in parts of the country is endemic, impeding developmental progress. Shortcomings and deficiencies of formal state institutions are obvious. On the other hand, as in Vanuatu, kastom in large parts of the country still provides cultural orientation, social security and political order to some extent. Papua New Guinea is also in a critical stage of its history as an emerging state. Both paths seem possible: further deterioration or stabilisation. The latter, again, depends on the implementation of good governance.

Bougainville is a highly interesting case. After almost a decade of war, Bougainville has over the last few years gone through a comprehensive process of post conflict peace-building which is one of the rare success stories of peace-building in today’s world, and it seems to have a good chance of becoming one of the equally rare success stories of state-building (be it in the context of Papua New Guinea or be it as an independent state). The reasons for this are that people on Bougainville are pursuing a new form of state-building that does not simply copy the Western model of the state. Rather, a home-grown variety of political order is in the making, utilizing customary institutions that already have proven to be effective and efficient in peace-building. If things go well on Bougainville, a positive accommodation of traditional non-state societal institutions and introduced state-based institutions will lead to a new political order that will provide a sound framework for peace, security and development. A more detailed analysis of the Bougainville case might provide insights in culturally contextualised forms of state-building that might also be useful for other emerging states.

The Solomon Islands find themselves in a critical phase of peace-building and state-building. Compared to Bougainville successes seem more tenuous, in spite of intensive external intervention to promote the process. After years of turmoil, violence was terminated and order restored by RAMSI (The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands). These are important achievements. However, building sustainable peace and political order remains profoundly challenging. To what extent are difficulties encountered due to a too narrow focus on ‘rebuilding’ state institutions, ignoring the hybrid character of political order and the resilience of communities on the ground? A sense of lack of local ownership could also be the source of problems. Although RAMSI is presented as a ‘regional’ endeavour, it is very much perceived (both within the Solomons and the international arena) as an Australian project. Success or failure in the Solomons hence will very much impact on Australia’s future stance in the region. An analysis of the situation on the ground in the light of the approach outlined in this chapter could contribute to fresh thinking about prospects in the Solomons.

Timor Leste (formerly East Timor) represents a somewhat different case than the others considered here, having a long history of embedded violence and occupation and an associated legacy of distrust and fractured political community. Despite the complex international dimensions to its current state of low intensity conflict it also provides many fascinating insights into the ways in which custom persists within the judicial and governmental sectors. Following the Indonesian withdrawal, Timor Leste has been the recipient of an extensive international state-building effort, with the early processes of institutional transfer occurring under the direct supervision of the UN. Sadly, just over eight years after the Indonesian withdrawal, the political, legal and security structures and systems at the heart of the new state have fractured, the capital has to rely on international security forces to maintain order, and an unexpected regional antagonism has emerged and hardened, splitting the capital and to some extent the country. Better understanding of the relationship between state-building efforts and how local people seek restoration of political community could contribute to better practice supporting the emergence of a state in the context of post-conflict peace-building and to what is likely to be a slow process of recovery in Timor Leste.

In Tonga, a Polynesian chieftain system developed into a constitutional monarchy in the 19th century, with the contemporary political arena still dominated by the royal family and the nobility. The country (which was not directly colonised) has thus taken a different route in the interaction between indigenous and liberal political governance than its Pacific Island neighbours and it has been associated with “not the weakness of authority or the threat of anarchy, but an excess of authority” (Campbell, 2006, p. 274). Over the past decade, however, Tonga has been making very slow moves towards greater democratisation. Democratic transitions are dangerous; Tongan democratisation had been proceeding relatively peacefully until a riot in the capital city in November 2006 destroyed large parts of the city and left several people dead. These events of 16 November 2006 were a traumatic experience for Tongan society, and the effects will be felt for a long time, both in the economic sphere (with a severe economic downturn) and in politics: the process of democratisation will become much more difficult. A case study of Tonga provides an important counterpoint to the other studies, since the state system has survived more or less in the same form for over 150 years. However, today different change dynamics are in place, and the impact they will have on traditional patterns of hierarchy, power and control are likely to yield different insights into state fragility and state effectiveness.

These six cases provide different combinations of Weberian-Traditional and Hybrid orders and each requires further research and analysis to determine precisely how it might be possible to blend, separate, combine different kinds of political order in order to strengthen social resilience, satisfy basic human needs and generate peace, order and security. Most political analyses have endeavoured to reinforce/impose a particular Weberian model of the state without any real recognition of the ways in which traditional and hybrid forms are or could generate different kinds of political behaviour, social and economic resilience and long term sustainable structural stability. What is very clear is that unless political hybridity is accorded more importance, the Weberian state systems will continue to be deficient and vulnerable; customary order will have difficulty generating the security it used to provide pre-colonisation and incorporation into the global capitalist economy, and situation of the Melanesian and Polynesian states of the Pacific will become increasingly precarious. A focus on hybridity will certainly allow more rapid movement towards the New Zealand government’s concept of Good Governance in the Pacific. Without it the prospects for achieving more capable, effective and legitimate governance will be problematic. [8]

8.9 Conclusions

So what does all of this have to do with the role of the state in promoting human security? In the first place, taking customary institutions, leadership and traditions seriously in thinking through ways of responding to and overcoming state fragility reflects the human security priority of putting the people and their needs first and developing institutions appropriate to these tasks. Second, focusing on political hybridity provides an excellent way of transcending simplistic dualisms in relation to thinking through the specific role of the state in post-colonial situations. Hybrid systems, for example, can be traditional and modern; Western and indigenous; formal democratic and informal customary; hierarchical and egalitarian. Third, it will ensure that more attention is paid to bringing state and community into closer liaison and developing more organic connections between both spheres of activity. This is critical to what I think about as ‘Grounded Legitimacy’ (Clements, 2008). This is the capacity of local peoples and communities to reconnect with those customs, values and traditions that have been subverted or destroyed by colonialism or war. Fourth, if there is any justification for thinking that indigenous peoples and/or those living in subsistence with nature are going to be good conservers of resources then focusing on political hybridity is one way of ensuring higher levels of sustainability to any political economy. Excluding customary custodians of fishing, agricultural and other resources from governance decisions is likely to result in rapid depletion of scarce resources. Finally, a good argument can be made for thinking that hybrid political institutions are likely to be more peaceable because efforts will be made to combine and blend customary methods of dispute and conflict resolution with more modern strategies. Thus it could be argued that hybrid political orders are more likely to generate more peaceable and harmonious communities than those which are built solely or exclusively on Westphalian principles. Having said this, however, political hybridity is no panacea for every political malady. It requires time, energy and effort to breathe life into both customary forms of governance and modern political systems. Whether one is talking about a Weberian model, a traditional model, or a hybrid , their successfulness will still hinge on ensuring maximal levels of societal participation in and engagement with the decisions that will determine whether emergent political systems will be capable, effective and legitimate in satisfying the basic human needs of citizens in post-colonial and post-conflict environments.

Resources and References

Review

Key Points

- Functional and effective statehood means that internal and external actors need to focus as much on the dimensions of legitimacy and citizenship as they do on strengthening the core functions of the state.

- Building new forms of state and citizenship that are based on a positive mutual accommodation between the Weberian State and Customary Order will transform hybrid political orders into emerging states that — in the long run — will generate new forms of governance beyond the model western state.

- Thus, in addition to enhancing the state’s capacity to generate security through reinforcing its core functions, a model of governance that is more sensitive to the multi-stranded character of political order in the Pacific will produce more resilient social and political systems, better equipped to deal with grievances and prevent the eruption of serious violent conflict.

Extension Activities & Further Research

- This chapter has focused on the necessity for more practical and academic attention on the social and communitarian sources of order, governance and legitimacy. This suggests that official and non-official development agencies need to direct more attention towards what might be called strength rather than vulnerability assessments in their analysis of the relationships between states and societies. Think of what difference it would make to your understanding of fragile states if you were to focus on sources of strength rather than weakness.

- Where states are lacking in capacity and effectiveness it ought to be possible to substitute community action for state action and vice versa. In all of this work it is important that more recognition be given to ‘connectors,’ i.e. individuals, groups and organisations capable of linking across boundaries of political, ethnic, linguistic and class differences. These connectors are critical to an adequate articulation between state and civil society and to the realisation of new concepts of grounded legitimacy in a post-colonial environment. What actors could be considered ‘connectors’ in your own environments? Are they strong enough to deal with those who might choose to divide rather than unite fragile social systems?

List of Terms

See Glossary for full list of terms and definitions.

- autochthonous traditions

- clientelistic state

- fragile state

- grounded legitimacy

- human security

- kastom

- political hybridity

- RAMSI

- sovereignty gap

- state capacity and effectiveness

- sustainable development

- Weberian state

Suggested Reading

Andersen, L., Møller, B., & Stepputat, F. (Eds.). (2007). Fragile states and insecure people?: Violence, security, and statehood in the twenty-first century. Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson, M. B. (1999). Do no harm: How aid can support peace—or war. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2007). Governance in post-conflict societies: Rebuilding fragile states. Routledge.

Clements, K. P. (2008). Traditional, charismatic and grounded legitimacy: Study by Kevin Clements on legitimacy in hybrid political orders. GTZ Sector Project: Good Governance and Democracy.

Regan, A. J. (2000). ‘Traditional’ leaders and conflict resolution in Bougainville: Reforming the present by re-writing the past? In S. Dinnen & A. Ley (Eds.), Reflections on violence in Melanesia (pp. 290–304). Hawkins Press; Asia Pacific Press.

References

Amburn, B. (2009). The Failed States Index 2007. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/13/the-failed-states-index-2007/

Andersen, L., Møller, B., & Stepputat, F. (Eds.). (2007). Fragile states and insecure people? Violence, security, and statehood in the twenty-first century. Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson, M. B. (1999). Do no harm: How aid can support peace—or war. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Ashraf G., Lockhart, C., & Carnahan, M. (2005, July). Closing the sovereignty gap: How to turn failed states into capable ones. ODI Opinions, 44. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/670.pdf

Australian Aid. (2006). Australian aid: Promoting growth and stability – A white paper on the Australian Government’s overseas aid program. https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/australian-aid-promoting-growth-and-stability-white-paper-on-the-australian-government-s-overseas-aid-program

Barcham, M. (2005). Conflict, violence and development in the southwest Pacific: Taking the indigenous context seriously (CIGAD working paper series 4/2005). Massey University. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/932

Boege, V. (2006). Bougainville and the discovery of slowness: An unhurried approach to state-building in the Pacific (Occasional Paper 3). Australian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Queensland.

Boege, V., Brown, A., Clements, K., & Nolan, A. (2009). On hybrid political orders and emerging states: What is failing – States in the global South or research and politics in the West? In M. Fischer & B. Schmelzle (Eds.), Building peace in the absence of states: Challenging the discourse on state failure (pp. 15–37). Berghof Research Centre for Constructive Conflict Management. https://www.berghof-foundation.org/en/publications/handbook/handbook-dialogues/8-building-peace-in-the-absence-of-states/

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2007). Governance in post-conflict societies: Rebuilding fragile states. Routledge.

Brown, M. A. (2007a). Introduction. In M. A. Brown (Ed.), Security and development in the Pacific Islands: Social resilience in emerging states (pp. 1–31). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Brown, M. A. (2007b). Conclusion. In M. A. Brown (Ed.), Security and development in the Pacific Islands: Social resilience in emerging states (pp. 287–301). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Campbell, I. C. (2006). Rock of ages: Tension underlying stability in Tonga. In D. Rumley, V. L. Forbes, & C. Griffin (Eds.), Australia’s arc of instability: The political and cultural dynamics of regional security (pp. 273–288). Springer.

Clements, K. P. (2008). Traditional, charismatic and grounded legitimacy: Study by Kevin Clements on legitimacy in hybrid political orders. GTZ Sector Project: Good Governance and Democracy.

Department for International Development. (2005). Why we need to work more effectively in fragile states. https://gsdrc.org/document-library/why-we-need-to-work-more-effectively-in-fragile-states/

Ghani, A., Lockhart, C., & Carnahan, M. (2005, June 30). Closing the sovereignty gap: How to turn failed states into capable ones. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/blogs/470-closing-sovereignty-gap-how-turn-failed-states-capable-ones

New Zealand’s International Aid & Development Agency. (2005). Preventing conflict and building peace. http://gdsindexnz.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/159.-Preventing-Conflict-and-Building-Peace-2005.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2005). The Paris declaration on aid effectiveness. https://www.oecd.org/dac/effectiveness/parisdeclarationandaccraagendaforaction.htm

OECD Development Assistance Committee. (2007). Principles for good international engagement in fragile states and situations. https://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/38368714.pdf

Parsons, T. (1966). Societies: Evolutionary and comparative perspectives. Prentice-Hall.

Regan, A. J. (2000). ‘Traditional’ leaders and conflict resolution in Bougainville: Reforming the present by re-writing the past? In S. Dinnen & A. Ley (Eds.), Reflections on violence in Melanesia (pp. 290–304). Hawkins Press; Asia Pacific Press.

Tönnies, F. (1957). Community and society. Transaction Books.

Turnbull, J. (2002). Solomon Islands: Blending traditional power and modern structures in the state. Public Administration and Development, 22(2), 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.211

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). Bedminster Press.

Long Descriptions

Figure 8.1 long description: A complex chart depicting the relationship between political leadership and citizens.

Media Attributions

- Figure 8.1 © 2019 Kevin Clements is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Interestingly, though, the important strategic document on development policy — the Accra Declaration for Action from September 2008 — does not mention the issue of legitimacy in the context of aid policies for countries in fragile situations. ↵

- Lecture to Ausaid February 2006 (publication unknown [ed.]) ↵

- In a high context culture like Vanuatu, for example, there has been a strong and robust reassertion of the importance of ‘Kustom’ and the power of traditional chiefs. In a low context culture like the Vatican, the current Pope has revived the tridentine Latin Mass and reasserted the primacy of traditional Catholicism over all other branches of Christianity. Both of these examples illustrate how traditional behaviour can reassert itself even in modern and post-modern time. ↵

- Editor’s note: This narrow conception of political strength represents another facet in the conventional development paradigm, the economic misconceptions of which were discussed in Chapter 1. ↵

- Editor’s note: However, in situations where the state authorities (or other authorities with the collusion of the state) mainly seek to exploit and dominate peripheral regions with little regard to their welfare this unwitting civil disobedience can be rather beneficial to human security. Examples include czarist Russia and corporate hegemony in Latin America. ↵

- For instance, in their presentation of the functions of the modern sovereign state Ghani et al. do not address these important issues of state—civil society relationships and legitimacy (See Ashraf et al., 2005). ↵

- Of course, both tasks are closely linked: effective state institutions will enhance the legitimacy of the state; and a notion of citizenship will make the establishment and the functioning of state institutions easier. However, both are separate tasks that deserve specific approaches. ↵

- The New Zealand International Aid and Development Agency (NZAID) defines good governance as the exercise of economic, political and administrative authority to manage a country’s affairs at all levels, in a manner that is participatory, transparent and accountable. It is also effective and equitable and promotes the rule of law. Good governance ensures that political, social and economic priorities are based on broad consensus in society and the voices of the poorest and most vulnerable are heard in decision making over the allocation of development resources. It includes essential elements such as political accountability, reliable and equitable legal frameworks, respect for the rule of law and judicial independence, bureaucratic transparency, effective and efficient public sector management, participatory development and the promotion and protection of human rights. (NZAID, 2005) ↵

A state in which a country is unable to guarantee order, security or the well-being of its citizens (Chapter 8).

The proper referent for security should be the individual rather than the state. In this paradigm a people-centered view of security is necessary for national, regional and global stability (Chapter 8).

A pattern of economic growth in which resource use is aimed at meeting human needs while preserving the environment so that these needs can be met in the present and through time (Chapter 8).

Coined by Kevin Clements, this term describes values, beliefs and practices that are grounded in traditions, customs and folkways, but capable of legitimating modern political, economic and social institutions (Chapter 8).

The state in Max Weber’s definition is a community successfully claiming authority on the legitimate use of physical force over a given territory. This legitimacy is either rational legal, traditional or charismatic. A Weberian state is characterised by the rule of law and state institutions divided into executive, representative, judicial, administrative and coercive agencies (Chapter 8).

The capacity and ability of state institutions to deliver the basic economic, social and political functions of governance effectively and legitimately (Chapter 8).

The incapacity of many states in the developing world to protect citizens and extend basic services to the whole population while being acknowledged by the international community as the sole effective and legitimate authorities in particular places (Chapter 8).

A state that depends on relations of patronage where its political culture is steeped in corruption and clientelist practices (Chapter 8).

Native to the indigenous traditions of place and locality (Chapter 8).

Political institutions and processes which blend or combine traditional and modern forms of governance and legitimation (Chapter 8).

Kastom is a pidgin word used to refer to traditional culture, including religion, economics, art and magic in Melanesia (Chapter 8).

The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) is a partnership between the people and Government of Solomon Islands and 15 contributing countries of the Pacific region. Its objective is helping the Solomon Islands to lay the foundations for long-term stability, security and prosperity (Chapter 8).