15 Issues with Human Rights Violations

Sabina Lautensach and Alexander Lautensach

This chapter is based on a paper presented at the 2011 GEIG conference (Lautensach & Lautensach, 2011b). We are grateful to Mr Farai Maguwu for contributing to this chapter.

Learning Outcomes & Big Ideas

- Explain how the notion of universal human rights is based on shared basic needs and the principle of justice.

- Recognize that human rights arose in three generations, addressing the civil-political, social-economic and environmental domains.

- Explain how only first and second generation rights can be granted universally; third generation rights are limited by the availability of natural resources. Nevertheless, they are vitally important for socioeconomic equity and environmental security.

- Understand that respect for and attention to human rights require a functional civil society; government and civil society uphold and strengthen each other.

- Be aware that without a guarantee for a modicum of human rights what level of human security might be achieved in a country can only be temporary.

- Explain how human rights are threatened by autocratic governments, corporate rule, crime and any group or organization that is not scrutinised by civil society.

- Describe how human rights can be strengthened by monitoring, enforcement, activism and education. The latter is essential for the development of civil society and can take many forms from state-sponsored to grassroots-driven and subversive.

- Acknowledge that particular challenges to enhance human security and cultural safety arise from the agenda of decolonisation.

Summary

An important area of initiatives to pre-empt and to mitigate threats to human security lies in the promotion of human rights. Efforts to promote them, however, must take into account an important distinction between those rights that can be granted under virtually all circumstances (i.e. civil, political and social rights) and those that depend on limited physical resources and are therefore not always grantable. The most comprehensive way to ensure human rights involves and relies on civil society at all levels. In turn, attention to human rights is required to maintain and perpetuate civil society. This raises particular challenges for those countries that are currently coping with a deficit in human rights. In this chapter the possible roles of non-governmental organizations are discussed in strengthening the recognition of human rights. We explore the possible roles of top-down reform programmes and compare them with the potential of grassroots initiatives. A particularly powerful example of the top-down kind is public education. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the influence of cultural context, the extent to which culture defines, and ought to define, moral norms such as rights and duties, as well as the limits of such definitions.

The discourse on human security continues to mirror the famous words of former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, “we will not enjoy security without development. We will not enjoy development without security, and we will not enjoy either without human rights” (Annan, 2005, p. 1). Annan’s words are further buttressed by Nelson Mandela who once said, “we do not want freedom without bread, nor do we want bread without freedom’.[1] Whilst the central role of human rights in promoting human security is no longer contested, the methodologies and strategies of putting human rights at the heart of human security are complex, culture sensitive and context specific. This chapter looks at how civil society can contribute towards the attainment of human security through building a culture of human rights using top down and bottom up approaches.

Chapter Overview

15.2 Two Kinds of Human Rights Differ in Their Relation to Human Security

15.2.1 The Criterion of ‘Grantability’

15.2.2 From Environmental ‘Rights’ to Environmental Demands

15.3 How Important Are Grantable Human Rights to Human Security?

15.4 How Can Human Rights Be Strengthened?

Extension Activities & Further Research

15.1 What Human Rights?

Modern international human rights law has been in existence for the past 70 years; the concept dates back much further, to the humanist thinkers who provided the philosophical platform for the French revolution. Instrumental in the idea was the notion that certain basic needs of subsistence were shared by all human beings – bodily integrity, food, shelter, health care, and freedom – and should therefore have moral significance (Jones, 1999, p. 58; Alston & Goodman, 2013). The language of human rights is found in every society and embedded in every culture and religion because it is based on the fundamental principle of justice. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (UN, 1948), the 1966 Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights constitute the backbone of international human rights law. ‘Human Rights’ is a buzzword that is often talked about but whose practical application remains a distant reality in many contexts and places. Many governments and non-state actors continue to pay lip service to the doctrine of human rights, exhorting one another to respect the rights of citizens whilst perpetuating structures and attitudes that jeopardise human rights or openly contradict them.

Many conceptualisations of human security are founded on human rights. As was explained in Chapter 3, basic needs are classified in a hierarchy. The right to have one’s needs recognised applies mainly to the bottom levels of that hierarchy, namely survival needs and safety. The discussion of climate justice in Chapter 9 established that rights come from the application of the justice principle to any situation that involves potentially unequal risks or benefits from areas beyond an individual’s control. Human rights developed historically in three stages, each based on agreement on a set of basic needs. The first generation of human rights, formulated in the 18th century, was civil and political in nature and was based on the cardinal value of freedom. The second generation of human rights refer to economic and social priorities, based on the cardinal value of human equality. A third generation of rights has been formulated, as illustrated by the UN and numerous major NGOs focusing on the right of every global citizen to enjoy freedom from fear and freedom from wants (Annan, 2005; UN, 2000). They add to the list of human rights specified in the UDHR (UN, 1948).[2]

In thirty articles, the UDHR specifies the human right to life, liberty, and security of person; to freedom from discrimination by race, creed, gender, and equality before the law and due process; to a fair and public hearing in case of criminal accusations; to be presumed innocent until proven guilty; to free association and nationality, to freedom of movement; to own property; to freedom of expression and of religion; to democratic choice of representation; to respect for human dignity; to work and to equal pay as well as to leisure; and to a basic humanistic education. Negative rights include freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, from arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile. Article 29 recognises appropriate duties and limitations of the rights of the individual for the common good but it does not mention ecological limits.

The third generation of rights consists again of negative rights, freedoms from certain undesirable states of being. Those freedoms are distinct from civil liberties and from the negative rights specified in the UDHR which both pertain to the functioning of civil society. They extend on the rights specified in Article 25 of the UDHR which refers to “the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services…”. In terms of environmental security those freedoms amount to certain quality attributes pertaining to environmental support systems, sometimes referred to as ‘environmental rights’.

The UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (UN, 2009) referred to ‘environmental rights’ as the right to clean air, safe potable water, adequate nutrition, shelter, the safe processing of wastes, and adequate health care. The document revealed no awareness of ecological limits of any kind that might curtail the availability of those resources and services. Even the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN, 2015) and the Agenda 2030 vision they promote leave unaddressed the question to what extent the rights of present-day humanity can be justifiably fulfilled while our present activities jeopardise the same rights for future generations. This question has been asked particularly in the context of the right to health care (Deckers, 2011; Jameton & Pierce, 2001). We will suggest that this question raises serious doubts about the validity of third generation human rights.

15.2 Two Kinds of Human Rights Differ in Their Relation to Human Security

15.2.1 The Criterion of ‘Grantability’

In earlier chapters in this textbook it was established that the purification of air and water, the provision of foods and shelter, and the processing of wastes are directly contributed by local ecosystems. It follows that the sustainable provision of those services depends on the biological integrity of those ecosystems (Karr, 2006; Ryan, 2016). Likewise, the health of a population is evidently affected by the state of its ecosystems (McMichael, 2001; Daw et al., 2016), as will be discussed in detail in Chapter 17. Accordingly, it would make sense for human communities to claim that ‘their’ ecosystems have a right not be harmed or diminished in their integrity. The fact that such a claim is not usually made, and that instead the demands pertain exclusively to the human recipients of those services (as in ‘the right to a clean environment’) represents, in our view, both a grave logical fallacy and a strategic error in judgment by human rights advocates.

The integrity of an ecosystem can — given sufficient care, experience and motivation — be maintained sustainably, barring any major external threats such as climate change. Among the conditions of such a policy would be that the total environmental impact of the human community that enjoys the ecosystem’s support does not exceed the sustainable maximum, i.e. the ecosystem’s carrying capacity. In contrast, claiming that the individual community member has a right to a certain quality of service makes no sense because no-one has the power to grant such a demand, not even the most absolute dictator, once the population’s impact has exceeded that threshold. Thus, those third generation ‘environmental rights’, including the ‘right’ to adequate health care or the entitlement not to be poor, belong in a different category of human rights, the category of ungrantable ‘rights.’ Being grantable, however, is an essential property of any right (Rawls, 1971). Therefore, a right that cannot be granted is no right at all (hence our use of inverted commas), and it makes no sense to promise or to claim it.

For example, the language in the MDGs and SDGs tends to frame the UN’s efforts to eradicate poverty (which is generally accepted as a moral duty) as fulfilling some kind of entitlement or right. This right is ungrantable in principle according to our above definition. Such an interpretation of a moral duty of the benefactor into a right for the beneficiary is also evident in documents from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR, 2004). The laudable intention was to “prevent slow large-scale progress from masking the loss or marginalization of individuals or minorities” (O’Neill, 2006, p. 13). Yet, only someone who believes that resources are unlimited can extend their allocation as a universal right.

The strategic error in judgment associated with claiming ungrantable ‘rights’ derives from the habituation effect that they it have on other rights. Such a claim diminishes the status of other rights to which realistic and legitimate claims could be made. For example, if the UN’s Human Rights Council added to the list of human rights the right to own a circus, clearly ungrantable, the entire list would as a result acquire a less serious, less binding, and more conditional appearance. This would be regarded as a disservice by most humanists who harbour genuine respect for human rights and concern for their enforcement. Some countries have laws that contravene basic human rights, such as outlawing homosexuality or freedom of expression. Such laws demean the way in which citizens respect (or not) the country’s laws in general. Similarly, ‘rights’ that contravene the laws of nature demean the status of all rights. The claiming of ungrantable ‘rights’ diminishes the sense of urgency with which all human rights ought to be respected worldwide. On the health care side, people become habituated to media images of sick individuals from poor countries and they take it for granted that whatever ‘right’ to health care those people or their advocates might proclaim is quite immaterial to their own privileged situation. The danger with this tacit distancing and discounting is that it is all too easily applied to more respectable rights, such as the right for political representation, to self expression, and to other presumably ‘self-evident’ rights, which compromises civil society worldwide.

The problem of ungrantable ‘rights’ does of course not diminish the need for guarantees to promote the environmental security of communities, especially when it comes to the world’s disempowered. After all, a moral duty merely commands us to give it our best effort—no more and no less—towards a moral goal. The concept of ecosystem integrity could function as such a goal, in formulating policy guidelines that would go a long way towards such a best effort, as discussed in Chapter 9 and Chapter 10. This approach might also lead to more balanced moral reasoning, away from the heavy emphasis on rights-based arguments and including arguments from utilitarian and virtue ethics. Arguments based on rights and duties often do not go far enough to promote human security in the form of effective policies and legislation because they often do not specify clearly enough what actually needs to be done. Grantable rights depend primarily on human behaviour and attitudes whereas ungrantable ‘rights’ depend heavily on environmental resources. In the light of this distinction, the question arises whether ungrantable ‘rights’ are of any use at all. Specifically we might ask, is there any benefit in insisting on the individual global citizen’s entitlement to adequate health care, a safe environment, adequate nutrition, considering that such provisions cannot necessarily be provided even under the best of intentions?

15.2.2 From Environmental ‘Rights’ to Environmental Demands

The preceding discussion emphasised the need to use rights-based arguments prudently when debating environmental security and human security in general, and to invoke grantable rights in different ways and on different occasions compared to those kinds of demands that are based on ungrantable ‘rights’. Heretofore, we will refer to the latter as ‘environmental demands’. We do not mean to insinuate that such demands have no place in the human security debate—on the contrary: The qualities of air and water, of nutrition, of shelter, of the ways of recycling wastes, and the status of public health are still among the best indicators to assess the environmental security of a community. And they can help bolster some legitimate rights-based arguments, namely in connection with the right to justice. We perceive at least three distinct benefits how environmental demands can render human security more achievable and more equitable.

First, in the case of a community or region that has not yet reached the maximum sustainable environmental impact, as for example, the West African country of Gabon, environmental demands can highlight situations of injustice and inequity. Based on claims for distributive justice they would help promote initiatives to elevate the quality of life for society’s poorest and their standard of living in the community. For example, elevated local incidences of cancer are often used to bolster demands for the authorities to explore possible causes and to implement local policies to improve prevention, screening and treatment. Likewise, environmental demands can direct public attention to environmental harms. Once public attention is gained, the evidence of ecological deterioration can inform policies to promote more sustainable practices and possible restoration. Thus, the ‘right’ does not refer to receiving certain benefits but to the equitable distribution of what benefits and sacrifices pertain in a particular situation.

Secondly, in situations where the maximum sustainable impact has already been exceeded — Ethiopia might serve as an example country — environmental demands serve to highlight that very circumstance. No other physical observation illustrates the fact of ecological overshoot more clearly than the widespread squalor caused by polluted air and water, famine, and the resulting abundance of ill health (McMichael, 2001). Vociferous demands for mitigation can make a significant difference politically, specially in the context of ecological overshoot as noted in earlier chapters. Against the worldwide opposition by powerful groups, environmental demands can provide the conduit for disseminating such information and educating the public (Rees, 2004; Lautensach, 2010). The language of environmental demands is one that everyone understands, even if those demands are bound to remain partly unmet. The causal connections between overshoot and poor human security have not yet widely entered the public’s awareness. Calls for fairness and equity can help to direct public attention to regions where overshoot is worst.

Thirdly, environmental demands are the mainstay of the discourse on justice in bioethics (Potter, 1988). An effective way to illustrate the widening gap between global rich and poor is to compare the environmental indicators that reflect the qualities of their respective lives, in addition to the often invoked data on per capita consumption. Regardless of the extent of overshoot, such comparisons highlight the injustice inherent in the global economic order, its trading schemes, and its underlying maldistribution of political power. While insisting on one’s right to a certain environmental quality is unlikely to lead to improvements, demands for equitable quality are more justifiable and authorities are more likely to heed them. This is the strategy that informs the SDGs.

Insisting on environmental demands in those contexts represents of course only the first step in an argument that necessarily leads to a discussion of Potter’s (1988) five modes of survival as outlined in Chapter 1. The SDGs are intended to lead us from the current prevailing global mixture of mere, miserable, and irresponsible modes towards acceptable alternatives. Unfortunately their chances of success are slim because many SDGs compete with each other for physical resources, as suggested in Chapter 3.

15.3 How Important Are Grantable Human Rights to Human Security?

Grantable human rights are the ones mentioned in the thirty articles of the UDHR (UN, 1948). They depend on social, moral and emotional capital such as goodwill, altruism, empathy, trust and open-mindedness. Thus, they do not depend on finite limits of physical resources. History abounds with well-intentioned efforts by powerful rulers to enforce measures for the ‘common good’, which arguably required that the individual rights and liberties of some or all of their subjects be curtailed. Article 29 of the UDHR serves that purpose, albeit not in a dictatorial way. Even in retrospect it is often difficult to assess whether such specific curtailments of freedom in fact led to preferable outcomes all around. Certainly human rights were often violated in the course of such measures. In principle, every law that is passed represents a compromise between benefits to society and sacrifices to individual autonomy.

As discussed in several of the preceding chapters, the next few decades will bring some drastic changes in lifestyle choices towards greater efficiency, reduced consumption, adaptation to global changes, and organisational reform, most likely accompanied by economic downturns and ultimately by a reduction in populations. Inasmuch as those changes are based on deliberate policy reform they will necessitate either an unprecedented amount of consensus on sacrificing current minority privileges or a draconian repression of individual autonomy (Bowers, 1993; Daly & Cobb, 1994; Lautensach, 2010).[3] Neither option sits well with advocates of human rights. Of course, avoiding the problem is always an option.: The 2005 quote by then Secretary-General Kofi Annan (2005, p. 1) given at the beginning of the chapter, from his report ‘In Larger Freedom’ advocating development, security and human rights for all (i.e. regardless of how many ‘we’ may be), eloquently catches the essential task while circumlocuting the important questions. Those questions include which rights are to be sacrificed for what degree of security, what kind of development can get us there, and how humanity is to make those decisions.

The challenge, then, will be to find the right compromises between rights and security — solutions that will find the approval of democratic societies at the national level and international acceptance at the global level. The concept of human security focuses on the security of the individual as opposed to the security of the state against foreign enemies or competitors. It builds on grantable human rights while remaining in tension with ungrantable ones — echoing the tension between achievable and unachievable SDGs as noted in Chapter 3. Human security postulates that it is for the security of the individual that the security of the state is guaranteed. By making the individual free from fear and want, the state enables him/her to actively participate in decision making and thereby making it unnecessary to govern through force and violence — or so the theory goes. Many security challenges facing the world today are closely connected to the failure by governments and by the international community to respect and uphold the grantable human rights and fundamental freedoms of peoples around the world. Whilst it is undeniable that some autocratic states have achieved notable economic gains without paying much attention to human rights, history teaches that in the long run such countries remain turbulent, unstable and can easily degenerate into civil unrest. (To further explore this problem of secure autocracies, see Extension Activity 4 in Chapter 21.)

One guideline for finding those proper compromises between rights and security, therefore, is the establishment and perpetuation of a stable civil society. Human rights must be respected and upheld sufficiently to allow this. Civil society augments the capacity of the state to protect human rights and it helps in holding perpetrators accountable for human rights abuses. Thus, it acts both as a watchdog against totalitarian tendencies and as a source of moral norms and ideals that govern society. Civil society campaigned for the downfall of dictatorships in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya and is responsible for similar uprisings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen. The role of civil society, augmented by social media, in setting the agenda for political reform at the national and international stage has been growing over the past decades. There is also a growing recognition of civil society by national, supranational, and international bodies such as the EU, AU, World Bank, IMF and the UN, as evident in international legislation and regimes holding states responsible for the protection of their citizens.

However, despite the significant gains attained by civil societies in many countries in driving the agenda for human security, more than half of the world’s citizens still suffer human rights abuses of one type or another. The state remains the biggest perpetrator of human rights violations. Freedom House reported in 2018 that 2.8 billion people (37% of the world’s population) have no say in how they are governed and face severe consequences if they tried to exercise the most basic rights, such as expressing their views or their sexuality, assembling peacefully, or organizing independently of the state (Freedom House, 2018). The fall of autocratic regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya due to popular uprisings, at a great cost in terms of human life and suffering, and continuing disorder in those regions challenge us to rethink the concept of security in the 21st century. The fall of these regimes and the ongoing upheaval in the entire Arab region demonstrate that it is the relationship between the state and civil society that will ultimately guarantee peace and security as opposed to the traditional notion where peace and security were understood only in the realm of international relations. A productive relationship between the two absolutely depends on a modicum of human rights, and in many countries that norm has not been attained.

15.4 How Can Human Rights Be Strengthened?

In advancing the human security agenda, and in light of monumental levels of human rights abuses recorded in many countries, a lot more needs to be done to ensure that state security becomes people centred as opposed to backing the security of regimes and political elites. Many regimes in the world still believe the security of the state is made possible through acquiring the latest military hardware on the market and by ensuring that state security agents receive the best training available. Billions of dollars are spent annually in activities and programmes that undermine the fundamental freedoms and basic human rights of the people, all in the name of national security.

However, a closer look at the United Nations Charter supports the notion that the organization was formed to create a climate where individuals can pursue happiness, freedom and prosperity that is built on the principle of mutual respect. In his speech to the UN General Assembly on 10 November 2001, the then Secretary General Kofi Annan reminded world leaders that ‘[t]he United Nations must place people at the centre of everything it does.’ After highlighting pressing issues to be tackled by the UN such as poverty, HIV/AIDS and political violence, Annan added that ‘the common thread connecting all these issues is the need to respect fundamental human rights.’ Thus there is no confusion at the level of the UN as to what needs to be done in principle to enhance human security and global peace. The biggest challenge to ensuring that the UN vision is transformed into a reality is bringing the UN Charter and the UDHR to the very people for whom the UN came into existence in the first place. An international Bill of Human Rights would serve as an important stepping stone (Sachs, 2003).

The task of putting human rights at the centre of human security should not be left to the UN alone, but rather should be ‘mainstreamed’ and be part of mechanisms and strategies adopted by governments to improve the security of their people. The problem with ‘mainstreaming’ is that it mainly focuses on 3rd generation ungrantable rights and particular visions of development that are mainly informed by the Conventional Development Paradigm (Trainer, 2016). This bias limits the potential benefits, and it diverts attention from the grantable social and political human rights that could sorely use some support in many parts of the world. The task of re-focusing on those rights must be spread to many more local and international human rights organizations so as to create sufficient advocacy at the grassroots levels, which can force governments to put human rights on their agenda. Civic education on human rights, targeting grassroots populations and political leaders, is vital in ensuring that any mechanisms and strategies taken by governments to improve human security follow a rights based approach.

The scourge of human rights abuses is not only the preoccupation of dictators under pressure. It can also be argued that the so-called ‘war on terror’ has created more insecurity for the global citizen than does the threat of terror. Human rights abuses committed by NATO forces in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, as well as other military forces elsewhere, have matched, if not surpassed, the collective atrocities committed by dictators and paramilitaries against their own people around the world during the same period. Similarly, failure by the International Criminal Court to investigate and based on verifiable evidence, prosecute Western leaders such as George Bush and Tony Blair for their involvement in starting and perpetuating the second Iraq war, which has claimed the lives of approximately 204 000 civilians as of 2019 (Statista, 2019), has undermined the work of the ICC which now stands accused of selective application of international law. Why is it that, ever since Nuremberg, it is only always the losers that are being prosecuted? In his address to the 2011 session of the African Union summit, UN Secretary General Ban Ki moon said the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “is a promise to all people in all places at all times.” Obviously there remains work to be done, and it will require substantial pressure from below.

Another category of human rights abuses comes from transnational corporations who take advantage of cheap labour and lax labour laws in developing countries to minimize their costs of production. Often those abuses are supported or at least tolerated by colluding government officials who benefit financially; even if the benefits are in some cases more equitably directed towards the state budget, the temptation is great for the government not to place too great an emphasis on questions about labour conditions and risk that the corporation relocates its operation. Transnational crime is another obvious threat, as Chapter 13 documents. Lastly, it is aid agencies themselves that have largely remained exempt from scrutiny in terms of their own human rights performance (Haslam et al., 2009, p. 253). The common condition to all of those threats is the absence of scrutiny by civil society.

15.5 Human Rights Education

There are many people around the world, in particular vulnerable groups such as women and children, who are either not aware of the existence of the UDHR or who do not think that it applies to them, or that it could benefit them. It is not possible for people to fight for and defend rights and entitlements, which they are not aware of. The absence of reports of human rights abuses in certain ‘stable’ countries does not necessarily mean that such abuses are not taking place; rather, it is a consequence of media bias (and possibly its manipulation) and a habituation to violence that has forced people to find security in silence.

The goal, then, is to create an open society where the state respects and protects the rights of its citizens, and where citizens are aware, concerned, and actively involved in governance and vigilance. This requires civic education that aims at teaching the very basic freedoms such as freedom of assembly, association and movement to the grassroots population, in particular the vulnerable groups such as women. This emancipatory kind of education builds on the traditions of critical theory and liberation pedagogy (see Case Study 15.1 and Au [2014]). It embraces all cultures who respect basic human rights and virtues (Banks, 2002).

The United Nations Decade for Human Rights Education and Training (1995–2004) prepared the ground for two subsequent phases. The Plan of Action for the Second Phase (2010–2014) of the World Programme for Human Rights Education emphasized that:

human rights education can be defined as any learning, education, training and information efforts aimed at building a universal culture of human rights, including:

- The strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms;

- The full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity;

- The promotion of understanding, tolerance, gender equality and friendship among all nations, indigenous peoples and minorities;

- The enabling of all persons to participate effectively in a free and democratic society governed by the rule of law;

- The building and maintenance of peace;

- The promotion of people-centred sustainable development and social justice. (UNHCR, 2010, n.p.)

The renowned cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1972, p. 261) defined culture as “the shared patterns that set the tone, character, and quality of people’s lives”. Most anthropologists, including Geertz, agree on definitions that refer not to observable behaviour per se but to the “shared ideals, values, and beliefs that people use to interpret experience and generate behaviour and which are reflected in their behaviour” (Haviland, 1996, p. 32). When acted upon by members of a society, culture gives rise to “behaviour that falls within the range of variation the members consider proper and acceptable” (Haviland, 1996, p. 32). This explains why the UN’s Action Plan refers to a ‘culture of human rights’, and a ‘universal’ one to boot. Without this fundamental and universal entrenchment of underlying beliefs and values, attention to human rights could come and go among the vagaries of fashion. On the other hand, the UN’s mandate for multiculturalism unfortunately prevents this universalism from becoming translated into effective action. Multiculturalism is informed by the principles of cultural relativism — the belief that any culture’s values and beliefs are as valid as any other culture’s. This principle of boundless tolerance is clearly not helpful in the case of cultures that do not recognise human rights; it stands in the way of the UN’s goal of strengthening human rights worldwide.

One way out of this conundrum would mean for the UN to recognize that, contrary to popular opinion, culture is not static. We can acknowledge cultural diversity while at the same time expecting cultures to develop over time toward more inclusive attitudes and a broader shared platform of values and ideals. Additional support should come from the other side of every right — much neglected in the human rights discourse — moral obligation or duty. Recognising that, regardless of our cultural differences, each of us has an obligation to buy into certain shared values — we have done so, for example, with the abolition of slavery – might help to make that shared global culture of human rights a reality.

Acknowledging that the creation of a human rights culture is not an event, but a long process that is aided by information dissemination, civic education and the gradual growth of political will, civil society has a big role to play in reaching out to the grassroots population as well as communicate at the intergovernmental level. Through formal and informal human rights education it will influence governments to enact and enforce legislations that further protect and promote the human rights and dignity of citizens. The biggest need exists obviously in countries and communities where populations have suffered state sponsored violence, where there is a general fear of state institutions and their agents by the citizens. For instance, in Zimbabwe, where state ‘security’ agents have been the biggest perpetrators of political violence, citizens get unsettled when they see army trucks in the village or any vehicle with government registration numbers. The media are absorbed in self-censorship for fear of forced closure, arson and arrest whilst civil society regularly goes into hiding. In those situations, education must begin through grassroots initiatives, NGOs, and external support by the international community. Following an appropriate change of government, the cycle will gain further momentum.

OECD counties, who generally enjoy a reputation of being beyond such struggles, should by no means be exempted (Banks, 2002). With regards the situation in the US, Au (2014) presents numerous examples of curriculum designs and classroom activities that increase awareness of racism and discrimination, introduce students to role models of resistance and empower students to engage in debates and advocacy. On the Canadian side the legacy of the infamous residential schools for indigenous peoples continues to exert its toll on the human security of First Nations. Beginning in the 1840s, government and churches colluded in policies that amounted to cultural genocide[4], interning more than 150,000 indigenous children after forcibly removing them from their families (Stromquist, 2015). More than 6,000 children perished in those institutions. The last residential school closed in 1996, 38 years after Canada had signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and 14 years after the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms had become law. A damning report by a national inquiry commission revealed the lack of government attention into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls, and the government’s attempts at covering that up, appeared at the time of writing (National Inquiry, 2019).

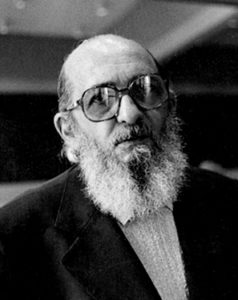

CASE STUDY 15.1

Paulo Freire and Liberation Pedagogy

During the height of the Cold War, many South American countries were ruled by military juntas that stayed in power through brutal suppression of any political opposition and blatant disregard for human rights. In return for US support they kept their countries free of socialist insurgency movements.

Paulo Freire (1921–1997) was a high school teacher in Brazil with a law degree who had spent much of his youth in poverty. At the time only literate Brazilians were allowed to vote, which he saw as a compelling reason to teach literacy to the poor. After some impressive successes with adult literacy programmes, he was imprisoned as a traitor by a newly risen military dictatorship.

Freire was able to flee into exile in the US and then Switzerland where he worked as an academic and expert for education policy and curriculum reform. His most famous work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) contributed significantly to the new field of critical theory of education. His particular contribution can be summarised as liberation pedagogy. It provides descriptive models for the ways in which autocratic regimes stay in power by manipulating the education system to the effect that the poor remain undereducated (and often illiterate) which prevents them from attaining any significant political power. More significantly, their lack of education keeps them from realising their own oppressed situation, acting as oppressors over each other on behalf of the powerful elites. His famous remedy was ‘conscientisation,’ the development of a political awareness and of the analytical skills to contradict and counteract the oppressive system. The basis for their active involvement is the empowerment that conscientisation brings about. His famous insight that the education process is never neutral in terms of values, assumptions, and power relationships remains as significant as ever in a time when ‘objectivity’ is being indiscriminately claimed by (and demanded of) journalists, commentators, trainers, and educators worldwide.

After the end of military rule in Brazil in 1979 Paulo Freire returned to Brazil where he continued his work as a researcher in education and political science and as Secretary of Education in São Paulo. The Politics of Education appeared in 1985. His work contributed substantially to the development of civil society in many postcolonial situations throughout the world and to the counterhegemonic efforts of oppressed and exploited people under all kinds of political systems. Freire served as a role model for thousands of teachers in poor neighbourhoods who understand only too well what irresistible power can come from the right kind of education.

Educational efforts are still ongoing to bring the legacy of racist policies to the awareness of Canada’s dominant ‘settler’ culture, to overcome decades of denial and coverups, and to work towards the active engagement of all sectors of Canadian society in the project of decolonisation. Particular significance in today’s multicultural societies is imparted on educational efforts towards the cultural safety of minorities (Lautensach & Lautensach, 2011a).

Education and advocacy for human rights almost invariably meets with resistance, for the same reasons as the circumstances that render it imperative; a society that is perpetuated by habitually violating human rights can hardly tolerate any efforts to discontinue such perpetuation. Often the resistance manifests as right-wing rhetoric, as casual disparagement in everyday discourse, or in passive resistance.[5] However, insofar as the education is perceived to threaten status quo power relationships such resistance tends to become violent. The example of the human rights movement in the US has been widely publicised but the focus across North America has still not widened enough to include other cultural minorities besides the obvious African and Latino ones, least of all the survivors of the continent’s indigenous populations. Violent resistance can emanate from non-governmental organisations such as the Ku Klux Clan — which shows that civil society by no means always sides with progressive movements — or it can through various covert and overt means be sponsored directly by the state. In 1960s Brazil this is what occurred in response to the efforts by the prominent counterhegemonic human rights educator Paulo Freire (see Case Study 15.1).

The all-important first step towards sustainable human rights in a worldwide framework will have to be a frank and open discussion of the issues at hand. Global limits, needs and capacities, rights and duties, means and ends must be made explicit and placed on the table in panel discussions, parliamentary debates, academic conferences, classrooms at all levels, governmental organisations, election meetings, public hearings, council meetings and any other public forum that promises leverage with the wider public. The longer the issues remain below the public horizon the greater will be the possibility that events will overtake deliberations.

Two particular issues seem especially pertinent and urgent for these discussions. One is the balance between moral relativism and moral universalism. Global human rights obviously represent the latter, but they also protect the right of cultural minorities to preserve and practice their traditional customs. In practice, this calls for the careful negotiation of compromises where traditions impinge on rights. Secondly, the discussion will have to address the obligations that come with rights, as we mentioned above, beyond the general provisions in Article 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Spelling out and respecting what obligations come with each generation of human rights might help resolve the problem of grantability and expedite the process of education towards more effective action plans.

Resources and References

Review

Key Points

- Calls for greater human security in a given situation are often based on claims that certain human rights are being neglected.

- The legitimacy of such arguments depends on what generation of human rights are being invoked; first and second generation rights work well for this purpose.

- Third generation human rights are not grantable and can therefore only be used to demand greater equity, not entitlements.

- The strengthening of grantable human rights requires a functional civil society.

- Liberation pedagogy represents a powerful tool for strengthening human rights and civil society under socio-political conditions that oppress people.

Extension Activities & Further Research

- What is civil society? Who is part of it? What is it good for? Explain with examples.

- The dilemma between rights and security can be addressed by weighing two opposing considerations: the extent to which human rights and liberties will have to be curtailed if the security is to be accomplished; and the extent that rights and liberties will be lost amidst anarchy, chaos, famine, disease and incessant warfare over diminishing resources, if security is not achieved (Homer-Dixon, 1999). Where do you stand in this debate? What assumptions, beliefs and values inform your position?

- In discussions around overpopulation, pro-natalist groups have emphasised, backed by considerable popular support, the ‘human right to reproduce.’ How do you assess this purported right in terms of its grantability? What ethical considerations apply in such an assessment?

- Human rights have been gradually accepted as a guiding universal moral norm that transcends cultural differences. This has culminated in the worldwide abolition of slavery in the 19th century, the proscriptions of cannibalism and infanticide, and other goals. Another innovation that human rights advocates are fighting for now is the proscription of the ritual mutilation of infants and children on religious or other cultural grounds. Opponents claim that such a sweeping measure would violate the rights of cultural groups to enact their treasured traditions. Where do you draw the line in this debate? What practices would you protect and what would you have outlawed? What are your distinctive criteria relating to human security?

- The gradual acceptance of human rights in Canada and other countries has been paralleled by the rise of numerous ‘humane’ societies for the protection of animal welfare. What do animal rights and human rights have in common? How can differences be justified, if at all? What other entities should also be imparted with rights, in your view?

- In British Columbia, human rights advocates focus on such issues as the plight of First Nations, refugees and other migrants, as well as the homeless. Choose one regional human rights issue relevant to your community and discuss to what extent the rights in question are grantable or ungrantable. How does this difference affect the ethical and political argumentation?

List of Term

See Glossary for full list of terms and definitions.

- civil society

- cultural relativism

- cultural safety

- grantability of a right

- right

Suggested Reading

Alston, P., & Goodman, R. (2012). International human rights. Oxford University Press.

Au, W. (Ed.). (2014). Rethinking multicultural education: Teaching for racial and cultural justice (2nd ed.). Rethinking Schools.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Books.

Heble, A. (Ed.). (2017). Classroom action: Human rights, critical activism, and community-based education. University of Toronto Press.

Lautensach, A. K. (2010). Environmental ethics for the future: Rethinking education to achieve sustainability. Lambert Academic Publishing.

Potter, V. R. (1988). Global bioethics: Building on the Leopold legacy. Michigan State University Press.

Rees, W. (2004). Waking the sleepwalkers: A human ecological perspective on prospects for achieving sustainability. In W. Chesworth, M. R. Moss, & V. G. Thomas (Eds.), The human ecological footprint (pp. 1–34). University of Guelph.

Stromquist, G. (2015). Project of heart: Illuminating the hidden history of Indian residential schools in BC. British Columbia Teachers Federation (BCTF). https://bctf.ca/HiddenHistory/eBook.pdf

References

Alston, P., & Goodman, R. (2012). International human rights. Oxford University Press.

Annan, K. (2005). In larger freedom: Towards development, security, and human rights for all – Executive summary. United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/A.59.2005.Add.3.pdf

Au, W. (Ed.). (2014). Rethinking multicultural education: Teaching for racial and cultural justice (2nd ed.). Rethinking Schools.

Banks, J. A. (2001). An introduction to multicultural education (3rd ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Bowers, C. A. (1993). Education, cultural myths, and the ecological crisis: Toward deep changes. State University of New York Press.

Chivian, E. S. (2001). Environment and health: 7. Species loss and ecosystem disruption — the implications for human health. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 164(1), 66–69. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/164/1/66

Daly, H. E., & Cobb, J. B., Jr. (1994). For the common good: Redirecting the economy toward community, the environment, and a sustainable future (revised ed.). Beacon Press.

Daw, T. M., Hicks, C. C., Brown, K., Chaigneau, T., Januchowski-Hartley, F. A., Cheung, W. W. L., Rosendo, S., Crona, B., Coulthard, S., Sandbrook, C., Perry, C., Bandeira, S., Muthiga, N. A., Schulte-Herbrüggen, B., Bosire, J., & McClanahan, T. R. (2016). Elasticity in ecosystem services: Exploring the variable relationship between ecosystems and human well-being. Ecology and Society, 21(2), Article 11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08173-210211

Deckers, J. (2011). Negative “GHIs,” the right to health protection, and future generations. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 8(2), Article 165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-011-9295-1

Freedom House. (2012). Worst of the worst 2012: The world’s most repressive societies. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Worst%20of%20the%20Worst%202012%20final%20report.pdf

Freedom House. (2018). Freedom in the world 2018. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_FITW_Report_2018_Final_SinglePage.pdf

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Books.

Freire, P. (1985). The politics of education: Culture, power, and liberation. Greenwood Publishing.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Haslam, P. A., Schafer, J., & Beaudet, P. (2009). Introduction to international development: Approaches, actors, and issues. Oxford University Press.

Haviland, W. A. (1995). Cultural anthropology (8th ed.). Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Heble, A. (Ed.). (2017). Classroom action: Human rights, critical activism, and community-based education. University of Toronto Press.

Jameton, A., & Pierce, J. (2001). Environment and health: 8. Sustainable health care and emerging ethical responsibilities. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 164(3), 365–369. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/164/3/365.full

Jones, C. (1999). Global justice: Defending cosmopolitanism. Oxford University Press.

Karr, J. R. (n.d.). Measuring biological condition, protecting biological integrity. Principles of Conservation Biology. http://sites.sinauer.com/groom/article23.html

Karr, J. R. (1997). Bridging the gap between human and ecological health. Ecosystem Health, 3(4), 197–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-0992.1997.00061.pp.x

Lautensach, A. K. (2010). Environmental ethics for the future: Rethinking education to achieve sustainability. Lambert Academic Publishing.

Lautensach, A. K. (2018). Migrants meet Europeans [Review of the book The strange death of Europe: Immigration, identity, Islam, by D. Murray]. Journal of Human Security, 14(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.12924/johs2018.14010024

Lautensach, A. K., & Lautensach, S. W. (2011a). Prepare to be offended: Cultural safety inside and outside the classroom. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 4(25), 183–194. https://www.academia.edu/1335239/Lautensach_A_and_S_Lautensach_2011_Prepare_to_be_Offended_Cultural_Safety_Inside_and_Outside_the_Classroom_International_Journal_of_Arts_and_Science_vol_4_25_183_194

Lautensach, S. W., & Lautensach, A. K. (2011b). Irreconcilable differences? The tension between human security and human rights. In L. Westra, K. Bosselmann, & C. Soskolne (Eds.), Globalisation and ecological integrity in science and international law (pp. 272–285). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

McMichael, T. (2001). Human frontiers, environments and disease: Past patterns, uncertain futures. Cambridge University Press.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2003). Human rights and poverty reduction: A conceptual framework. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Poverty/DimensionOfPoverty/Pages/Guidelines.aspx

OHCHR. (2010). Plan of action for the second phase (2010–2014) of the world programme for human rights education (A/HRC/15/28). https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/Compilation/Pages/PlanofActionforthesecondphase(2010-2014)oftheWorldProgrammeforHumanRightsEducation(2010).aspx

O’Neil, T. (Ed.). (2006). Human rights and poverty reduction: Realities, controversies and strategies. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/publications/1652-human-rights-and-poverty-reduction-realities-controversies-and-strategies

Potter, V. R. (1988). Global bioethics: Building on the Leopold legacy. Michigan State University Press.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Harvard University Press.

Rees, W. (2004). Waking the sleepwalkers: A human ecological perspective on prospects for achieving sustainability. In W. Chesworth, M. R. Moss, & V. G. Thomas (Eds.), The human ecological footprint (pp. 1–34). University of Guelph.

Ryan, M. (2016). Human value, environmental ethics and sustainability: The precautionary ecosystem health principle. Rowman & Littlefield.

Sachs, J. D., & McArthur, J.W. (2005). The Millennium Project: A plan for meeting the Millennium Development Goals. The Lancet, 365(9456), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17791-5

Sachs, W. (2003). Environment and human rights. Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, Energy. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:wup4-18117

Singer, P. (1975). Animal liberation: A new ethics for our treatment of animals. HarperCollins.

Statista Research Department. (2020, August 11). Number of documented civilian deaths in the Iraq war from 2003 to July 2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/269729/documented-civilian-deaths-in-iraq-war-since-2003/

Stromquist, G. (2015). Project of heart: Illuminating the hidden history of Indian residential schools in BC. British Columbia Teachers Federation (BCTF). https://bctf.ca/HiddenHistory/eBook.pdf

Trainer, T. (2016). Scrap the conventional model of Third World “development”. Mother Pelican, 12(12). http://www.pelicanweb.org/solisustv12n12page5.html (Reprinted from Scrap the conventional model of Third World ‘development,’ 2016, November 5, Resilience, https://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-11-05/scrap-the-conventional-model-of-third-world-development/)

United Nations. (n.d.). About the Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

UN. (n.d.). UN Millennium Development Goals. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

UN. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html

UN. (2000). We the peoples: The role of the United Nations in the 21st century. https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/We_The_Peoples.pdf

UN Development Programme. (1994). Human development report 1994: New dimensions of human security. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-1994

UNDP. (2007). Human rights and the Millennium Development Goals: Making the link. https://gsdrc.org/document-library/human-rights-and-the-millennium-development-goals-making-the-link/

Westra, L. (2005). Ecological integrity. In C. Mitcham (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics (Vol. 2). Macmillan.

.

Media Attributions

- Figure 15.1 © Slobodan Dimitrov is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Address by Nelson Mandela given 1 August 1993 at Soochow University, Taiwan (accessed 20 July 2019). ↵

- It is interesting to note how exclusively human rights are restricted to the human species, but include even the most incompetent and disabled individuals (such as newborns and comatose patients) while excluding even the most sentient members of other species (such as the great apes and cetaceans). This ‘speciesist’ distinction seems rather arbitrary and lacks logical justification (Singer, 1975) but is nevertheless implicitly accepted by most authors in the literature on rights, as well as by the public at large in many cultures. ↵

- For example, a nationwide shortage of food might force a government to enforce a rationing system, as happened in WWII Europe. Such a system forces people with access to food, such as farmers, to deliver most of their produce to the state who distributes the food equitably as needed among the population. Transgressions, as by black marketers, are prosecuted and punished severely. Privileges are sacrificed and autonomy curtailed in order to maximise the common good and to minimise the effects of malnutrition. ↵

- Particularly revealing for those who know European history is the phrase “final solution” of the “Indian problem” in the summary of the legislation (Stromquist, 2015). ↵

- Popular excuses for historical human rights violations tend fall into the following three categories: “it wasn’t all that bad”; “others did it, too”; and “all perpetrators and victims are long deceased.” (Lautensach, 2018) ↵

A moral or legal entitlement to have or obtain a particular good or service or treatment, or to act in a certain way. All rights come with obligations and are governed by limits, which renders them particularly contestable (Chapter 15).

The social sphere of voluntary cooperation, distinct from the spheres of political and economic competition (Chapter 4). The ‘public sector’ (public institutions outside of government) and the ‘private sector’ (for-profit organisations). The former can include any organisation, association, community of shared interests or beliefs that contribute to what might be construed as ‘public interest’ (Chapter 15).

The belief that any culture’s values and beliefs are as valid as those of any other culture. This belief gained acceptance as a principle as people became more critical of traditional colonialism and its wholesale oppression of Indigenous cultures worldwide. It went hand in hand with moral relativism, which is equally unhelpful for anyone searching for ways to strengthen human rights (Chapter 15).