Section 3: Consent & Sexual Violence Training Guide

Facilitation Considerations

It is recommended that the facilitators for this training be experienced with trauma-informed approaches to sexual violence and connect this knowledge to specific facilitation skills to enhance the safety and learning of the audience. Facilitators should also be familiar with decolonizing, intersectional, and inclusive approaches to sexual violence and consent. If these are areas where facilitators need more knowledge, they should spend roughly 2-3 hours going through the recommended resources below. Regardless of audience, it is crucial that facilitators acquaint themselves with these bodies of knowledge in order to hold a relatively safe space for adult learner engagement on the topic of sexual violence.

It is also recommended that facilitators allocate at least 30 minutes before and 30 minutes after the training delivery for preparation and to be explicitly available to answer individual questions or inquiries from learners after the training delivery. After the training, facilitators are encouraged and, if needed, to debrief the positive takeaways and areas of growth (if any) from the experience with a peer or supportive person (see examples of debriefing questions in Section 2: Self-Care and Community Care).

General Principles of Trauma-informed Facilitation

- Emotional safety of learners

- Cultural humility

- Awareness of power dynamics in the room

In addition to sections 1 and 2 of this guide that refer to best practices in trauma- informed facilitation, we would like to offer the three principles mentioned above to guide the essence of this workshop’s facilitation. We recommend that you consider each of these principles as you prepare to create a safe environment for all learners.

If possible, we encourage you to inquire about learners’ backgrounds before the training (e.g., demographics, area of study, roles/relationships in the group). This information will provide you with the opportunity to prepare and adjust the content, materials and resources to be shared with learners. This will also give you the opportunity to examine your role in relationship to the learners.

As a facilitator, it is imperative to model honesty, openness/lack of judgement and humility when delivering a trauma-informed training that will examine personal and societal values. We encourage you to see this as an opportunity to facilitate a space that welcomes vulnerability and supports diverse experiences. During the training, we encourage you to name the challenges present in some discussions or information and to celebrate this as a learning opportunity and make yourself available for direct check-ins with learners.

Resources for facilitators to learn about trauma-informed facilitation:

Facilitating Discussion about Consent

As a facilitator, you will want to consider how to tailor the topic of consent and sexual violence to different audiences and contexts. In addition to helping learners understand the legal definition of consent, you will want to highlight how consent is an ongoing process (not a one-time event) of discussing boundaries and what people are comfortable with. Placing consent into a larger context will require you to address issues such as power dynamics, relationships of all kinds, and myths about sexual violence. As well, you will want to help learners develop the skills they need to navigate issues and challenges that arise in their everyday lives. Below are some suggestions on how to increase awareness and “deepen” conversations about consent.

Help learners to understand that consent relates to more than sex

While this training focuses on the prevention of sexual violence, it is helpful to connect the topic of consent and sexual violence to consent in our everyday lives. You will want to highlight how we already ask and give consent to many activities in our everyday lives and how the more we practice consent outside of sexual situations, the easier it is to practice consent in relation to sex.

As you facilitate discussion you can highlight ideas such as:

- When we talk about “everyday consent,” we are talking about the ways that we make another person feel heard, safe, and comfortable. It’s about how we communicate, listen to and acknowledge boundaries. Sexual consent mirrors all of these things.

- We sometimes feel awkward about asking or giving consent in sexual situations. It can be helpful to remember that we already practice consent in our everyday lives. For example, we practice consent when we ask someone if it’s okay to post a photo of them online or whether it’s okay to give them a hug or if it’s okay to share their email address with someone else.

- In the context of interpersonal relationships, consent also applies to things like how fast a person drives a car with you in it or whether they show up unannounced at your front door or whether they respect your decision to not spend time together for a few days. A good sign of a consensual relationship is that you don’t feel pressured to do things that you aren’t comfortable doing.

Help learners to challenge social expectations and gender stereotypes

The topic of consent generally requires discussions about how we are expected to act in various social situations and what kind of changes we need to make so we can all contribute to creating “communities of consent.” In order to do this, learners will often need to reflect on their own beliefs and values about consent, consider the new information that you share with them (e.g., the legal definition of consent or your institution’s sexual violence and misconduct policy), and then apply this to their own lives. You may encounter confusion, resistance, self-blame, anger and frustration as people reflect on their own experiences and learn to think about consent in new ways.

Some of the common responses that you might hear include:

- “They didn’t say no.”

- “We were drunk.”

- “She was asking for it because of what she was wearing.”

- “You need to be more assertive.”

You may want to review Section 2: Responding to Common Myths about Sexual Violence.

As well, while ideas about consent, dating, and relationships are continuing to change, most people face pressures and challenges on how to think, behave, and act in these situations. One way of initiating conversations about these types of expectations and pressures is to make connections to popular culture (e.g., movies, TV shows, advertisements, song lyrics, and music videos) and explore the way people of all genders are portrayed. You could ask: “How are we expected to act, speak, dress, and conduct ourselves based on our assigned sex at birth?” or “Does it seem like it’s always the “guy” who has to ask for consent and the “girl” who has to give it?” During the discussion, you can say something like: “Stereotypes and expectations around who takes charge or who can show emotion can limit our confidence in speaking openly about what we need in a relationship or during sex.”

Help learners to develop communications skills that make sense for their relationships and context

In general, learners will benefit from opportunities to discuss and practice strategies for asking and giving consent in different types of relationships. You may want to discuss topics such as verbal vs. non-verbal communication, power dynamics (“What might you say/do if the person asking was your classmate? What might you say/do if the person asking was your boss?”), and different types of relationships (e.g., relationships between friends or family members, relationships between adults and children, sexual or romantic relationships).

As you facilitate discussion, you can highlight ideas such as:

- Consent is not just about saying “no” when you are uncomfortable. When we talk about consent, people often think about the phrase “no means no,” meaning if you feel uncomfortable with an activity then you are refusing consent. While this is true and all “no”s should be respected, thinking about consent in this way places responsibility on the resisting person and conveys the idea that consent is always “negative.” Discuss how consent (legally and otherwise) is affirmative and requires a clear and enthusiastic “yes.”

- Similarly, just because someone isn’t saying “no,” it doesn’t mean that they are saying “yes.” Discuss how peer pressure, power dynamics, social and cultural expectations, substance use, anxiety and fear are just some of the factors that can contribute to a person’s silence if they’re uncomfortable with a particular situation.

- Consent is not just about one person asking and the other person or persons saying “yes” or “no.” Everyone involved in a situation/relationship has the responsibility to communicate and to listen to what is acceptable and comfortable for everyone involved.

- Asking for consent in sexual situations does not “ruin the mood.” Challenge this idea and help learners find ways to ask and give consent that are exciting, e.g., discuss verbal and non-verbal communication. You may want to ask questions such as “If we are afraid to ask or give consent because it might ruin the mood, what might this say about our relationship(s)?” or “If we are worried about ruining the mood, is it possible that we are feeling pressure from ourselves or others?” You can also say something like “The mood is always much more positive when everyone involved feels completely comfortable.”

| Verbal (using words) | Non-verbal (using body language) |

|---|---|

|

|

| Verbal (using words) | Non-verbal (using body language) |

|---|---|

|

|

Below are some considerations for specific groups of learners.

LGBTQ2SIA+ Learners

Some research has shown that transgender and non-binary youth identify consent and communication as an important, though often absent, part of sexual health education (Haley et al., 2019). The same is true for many people who are queer or are involved in queer sexual or romantic relationships. Because sexual health education often omits deep exploration of gender identity and queer sexual attraction, practices, and relationships, even when consent education is included in sexual health education teaching, LGBTQ2SIA+ young people may not have consistent or firm foundations in asking for or offering consent (Segalov, 2018). On the flip side, this does mean that LGBTQ2SIA+ people can develop their own rules and practices around consent without the constraints of conforming to mainstream societal gender and sexual expectations (Edenfield, 2019). Still, intersecting oppressions and identities mean that queer relationships are not immune from unbalanced power dynamics (Kahn, 2015). For example, a relationship between a transgender person and cisgender person or a non-monogamous relationship between people of different races and abilities may still involve reckoning with imbalances in privilege.

Especially for transgender, non-binary, Two-Spirit and other gender diverse people, consent, and communication around healthy boundaries might involve talking to potential sexual and romantic partners about what words to use when referring to their body parts or which terms to use when referring to their relationship (e.g., partner, spouse, significant other, datemate, joyfriend, genderfriend). Research also suggests the importance of including learning materials and resources that have been developed by and for transgender, non-binary, Two-Spirit and other gender diverse people (Braford et al., 2019).

Queer social scenes can sometimes revolve around nighttime bars or clubs. Because queer sex and relationships have been historically forced underground by law enforcement and legislative systems, these clubs and bars continue to be one of the few places where LGBTQ2SIA+ people can meet each other for sexual or romantic encounters (Raymond, 2019). Consent for sexual activity may be wrongly assumed by patrons of these bars and clubs. Though not exclusively attended by queer people, bath houses and darkrooms are parts of some queer experiences. Consent may not often be explicitly given or asked for. However, there is a need and opportunity for the lack of consent culture in these spaces to change (Raymond, 2019; Segalov, 2018).

There may be a false assumption of safety from sexual violence from within LGBTQ2SIA+ communities. The LGBTQ2SIA+ community is often seen as a safe haven from those who may violently target queer and transgender people, so victims and survivors of sexual violence may be reluctant to disclose that they have been harmed by sexual violence from those within their community.

Other facilitation strategies to consider:

- Introduce yourself using your pronouns (she/her, he/him, they/them, etc.). Invite learners to do the same whenever they interact with you or each other, if they are comfortable doing so. This ensures a safe environment for people of all gender identities.

- Learn the difference between sex, gender identity, attraction, and presentation. There’s a helpful interactive activity by Trans Student Educational Resources called the Gender Unicorn. If you have time, you can share this with learners so they can map out their own experience of sex and gender. (As well, see Section 2: Sex, Gender, and Gender Identity).

- As part of the training, offer community and campus resources for queer victims of sexual violence that are culturally relevant (i.e. resources for Two-Spirit people, queers of colour, disabled queers, religious queers, etc.). Remember that people in the LGBTQ2IA+ community are disproportionately targeted by perpetrators of sexual violence. Because of the lasting societal prevalence of homophobia, transphobia and queerphobia, they may be isolated from supportive networks of families and friends. As well, experiences with medical professionals and the criminal justice system may not offer culturally competent support or a sense of safety for queer and racialized victims of sexualized violence. Likewise, victims of queer sexual violence may be reluctant to seek support or report the harm done to them (e.g. a straight, cisgender man may feel shame about being victimized by another man and choose not to seek support).

- During discussions about sexual violence in our society, acknowledge and help learners to understand the intersecting oppressions faced by LGBTQ2IA+, folks of colour and those who are disabled and Indigenous.

International Students

There are multiple barriers which may prevent international students from learning about the law, their rights, services and options available to them. Language and English proficiency is a barrier to the successful participation and smooth acculturation into the host society and transition to their academic studies. Many domestic students have a broader understanding about sex and openly engage in discussions having been exposed to media and sex education. In contrast, international students will have different views of sex guided by their own cultural beliefs, values and norms. When it comes to the topic of consent, its significance in relationships and dating may be disregarded and not understood (Blackman, 2020; California State University, San Bernardino & Martin, 2015; Levand, 2020).

As well, some cultures view talking about sex as taboo and it is not only discouraged, it is not acceptable. International students may not feel comfortable talking about sex in public, in workshops or in class, and extra effort should be made to allow space that is inclusive. This can be accomplished by acknowledging the cultural diversity of other countries, and by providing language specific supports that include translated materials and resources for ongoing community support if needed.

Other facilitation strategies that may be helpful:

- Encourage learners to share their understanding of consent by reflecting on their values, beliefs and cultural expectations. Some may share how the observed behaviors of domestic students conflicts with their own belief system about sex and how this can cause confusion. If required, extra time should be allotted to ensure the concept of consent is understood and the punitive consequences for when it is not accepted. This is to ensure that all learners understand.

- Some international students may find it difficult to speak English and not have the vocabulary to convey their emotions, feelings and needs. Or, they may be uncomfortable with saying “no” and express themselves through body language. Providing examples of language and words which could mean “no” is important. E.g., “I don’t want to… stop…”

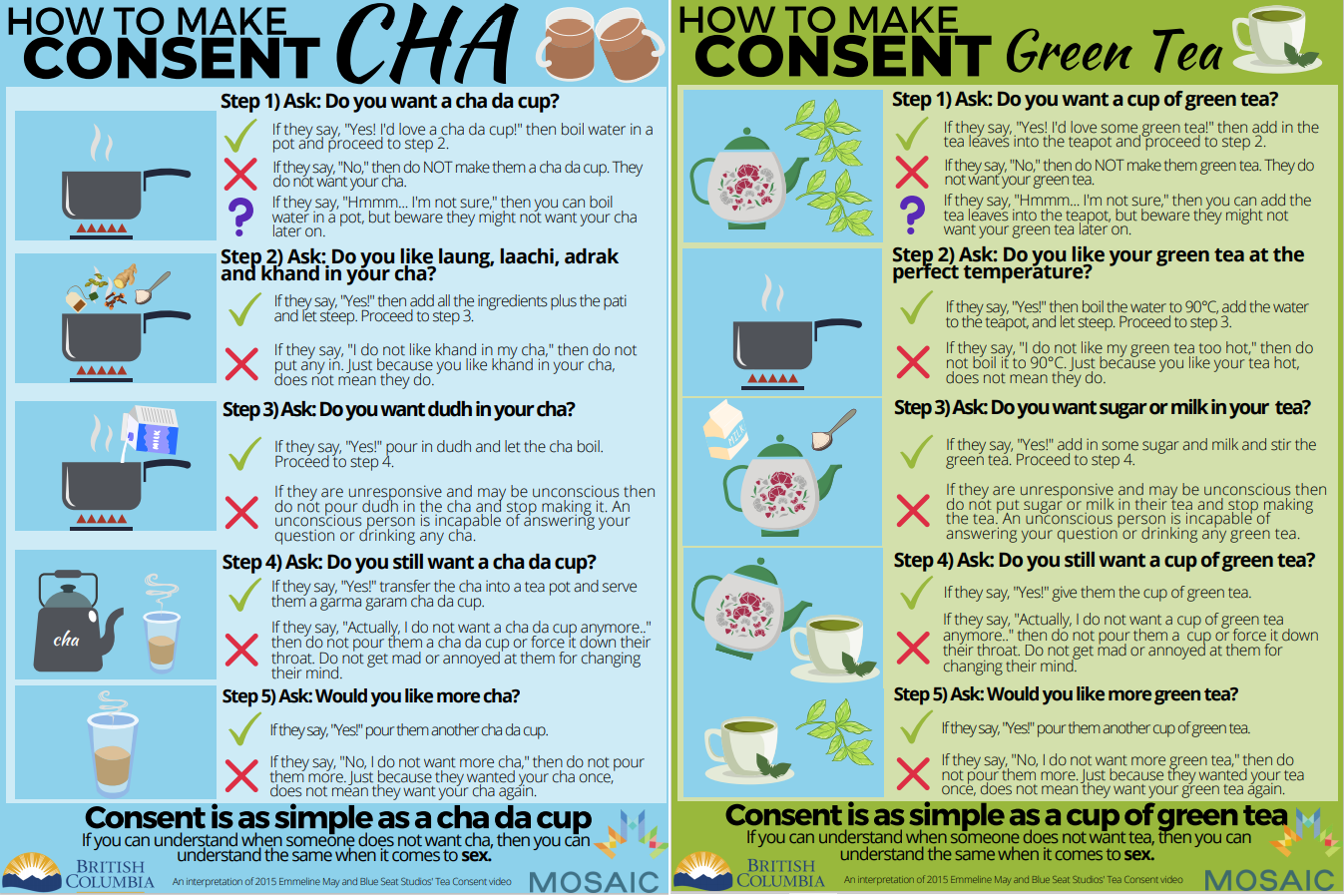

How to Make Consent Cha/Green Tea

These handouts were developed by MOSAIC as part of sexual violence prevention education workshops for international students in BC. They are based on the popular YouTube video Tea Consent that helps people to understand consent by comparing it to a cup of tea. Used with permission.

Downloads the handouts here: How to Make Consent CHA Posters MOSAIC [PDF].

Indigenous Perspectives on Consent

When providing training on consent & sexual violence in Indigenous contexts, it can be helpful to think about consent from a holistic perspective. In general, consent education focuses on consent within all relationships, not just sexual or romantic relationships. As well, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners may find it helpful to discuss consent from the perspective of interconnected relationships within a community.

Although there is a great diversity in Indigenous worldviews, there are also many commonalities. Many Indigenous cultures include the concept of “All my relations” which means that we are connected to all things – people, plants, trees, animals and rocks – and we need to look after each other (Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, 2020). Many Indigenous people have made connections between consent over the body and consent over land. For example:

“In order to increase the recognition of free, prior, and informed consent over Indigenous territories we need to simultaneously build up the ways that consent is supported around people’s bodies. If discussions are taking place about violations of industry on Indigenous lands, we should also be talking about the violations of people’s bodies. We cannot have healthy families, communities, and nations on the land while people’s bodies continue to experience violence. It is through listening to survivors of violence, asking them about solutions to land violations, and building in teachings about consent that we will have healthy nations” (Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016, p.17).

Below are several suggestions for including an Indigenous perspective when discussing consent and sexual violence:

- Consider ways of incorporating cultural practices into the workshop. For example, you could include an art-making activity such as beadwork or colouring pages by Indigenous artists and activists (Sterritt, 2016). This can help to provide a culturally safe environment in which to discuss consent from a holistic perspective.

- Share information about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) by including examples of discussions from current news media or sharing the report from the National Inquiry. Or, work with your institution to host the REDress project or share images from this art installation project by Jaime Black which brings attention to MMIWG (Brulé, 2018).

- Discuss Indigenous land sovereignty and self-determination. For example, you might say: “In order to address sexual violence in our society, the inherent rights of Indigenous people under Canadian and international human rights law must be recognized.” You can make links to current issues such as pipeline projects or treaty negotiations.