Educational Pathways

Chapter Audience:

Administrators

Administrators Program Managers

Program Managers Faculty

Faculty

What Are Educational Pathways for Micro-credentials?

Educational pathways are about creating access to education. In the context of micro-credentials, it’s about using these short programs as on-ramps to more learning, preparing undergraduates for the world of work by giving them skills that are recognized and sought by employers, and updating the knowledge and skillset of alumni in response to their changing work environment. To create such access, micro-credentials must be integrated into the existing credential ecosystem so that they are not isolated educational experiences. Thus, educational pathways are about integrating lifelong learning into the academic system.

The term “educational pathways” covers a range of connections in the credential ecosystem. These terms are explained below:

- Stacking. Stacking usually refers to non-credit programs. It describes how larger educational experiences are built from smaller, individually recognized ones. Usually what’s stacked are individual courses that together form a micro-credential; or alternatively, smaller micro-credentials are stacked into a larger one that recognizes a coherent set of skills or competencies. For example, a learner who successfully completes a micro-credential in photography, a micro-credential in graphic design, and a micro-credential in Adobe Photoshop could be recognized with a “mega micro-credential” in visual communication whose learning outcomes combine elements from each of the smaller micro-credentials. The chapter Design Considerations: Practical Guide provides information about the different ways to stack a program in the section Micro-credential Program Structure.

- Laddering. Laddering is similar to stacking in the sense that it uses smaller programs as building blocks toward a larger one. However, the term is usually reserved for credit-bearing micro-credentials that provide on-ramps to larger academic programs. For example, completion of a micro-credential could give learners advance standing when entering a degree program, allowing them to enter in the second year of the program (i.e., the micro-credential is recognized as equivalent to the courses normally taken during the first year). Laddering is a connector between smaller units of training and larger programs. See BCIT Ladders Micro-credentials into Associate Certificate for an example.

- Credit transfer. Credit transfers are similar to laddering in that completion of a small training experience entitles the learner to gain advanced standing in a larger program, but at another institution. An example would be where a credit-bearing micro-credential completed at one post-secondary institution is recognized and provides advanced standing for admission to a larger academic program at another institution.

- Prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR). This usually refers to the translation of informal or non-formal learning experiences into credit-bearing recognition. Academics assess the merit of the learning that took place outside of a post-secondary environment and award credits that correspond to credit-bearing offerings at the institution, as appropriate. See the section Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition for more information.

- Credit bank. Credit banks are a form of PLAR where instead of assessing a learner’s knowledge and skills obtained through non-formal means, the non-formal program itself is assessed. If the non-formal program is deemed worthy of post-secondary recognition, then PLAR credits for the non-formal program are granted. This enables learners who have completed the non-formal training to receive credits without having to provide evidence of learning beyond completion of the program. See the section Credit Bank for more details about the TRU credit bank and the possibility of a province-wide credit bank to recognize and translate micro-credential learning into credits.

- Direct assessment. Direct assessments are like challenge examinations. They allow adults who have acquired knowledge and skills through informal and non-formal experiences (such as on-the-job training) to be recognized with a micro-credential without having to complete the program. See the section Direct Assessment for more details.

Figure 1, shown below, depicts how these terms link different types of credentials offered in and out of post-secondary institutions.

As explained in more depth in the section KPU’s Approach to Micro-credential Laddering, opening up educational pathways between micro-credentials and other credentials makes learning more accessible. However, it must be done in a thoughtful way to ensure that the larger program’s learning outcomes are not jeopardized in the process.

Why Create Educational Pathways?

The short duration of micro-credentials makes them achievable and this makes them accessible to adult learners, whose other commitments may make traditional macro-credentials (certificates, diplomas, and degrees) daunting if not impossible to undertake. At the same time, completing a micro-credential gives adult learners a head start if they wish to continue with further training. In this way, a micro-credential can serve as a gateway for further education.

In a 2020 study sponsored by the B.C. Council on Admissions & Transfers (BCCAT) (Duklas, 2020), 74 per cent of the Canadian post-secondary institutions who participated in a survey reported that their main reason for developing micro-credentials was to provide access to further education and 42 per cent said their top goal was to scaffold learning opportunities. Thus, Canadian institutions realize the importance of forging educational pathways between micro-credentials and the rest of their credential ecosystem.

The importance of educational pathways is reflected in the Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021) where three of the nine elements refer to ways in which micro-credentials should fit with other learning opportunities at a post-secondary institution.

Learning Pathways

Micro-credentials may be credit or non-credit bearing, and this should be made explicit to learners prior to enrolment. In order to create meaningful learner pathways, micro-credentials should be developed in a manner that shows how they:

- relate to other credit and non-credit bearing opportunities,

- connect with existing larger units of learning, and,

- remove barriers and create clear and varied pathways for learning.

Post-secondary institutions are encouraged to collaborate internally and with other post-secondary institutions in developing micro-credentials to increase opportunities for transfer, laddering or stackability.

Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition

Prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR) should be considered when offering micro-credentials.

Post-secondary System Recognition & Transfer

Micro-credentials should facilitate learner mobility across institutions, industries, and credentials, and not introduce barriers to learning, transfer or labour market participation.

Micro-credentials, where possible, will integrate with existing credit transfer processes.

Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021).

How to forge pathways between informal and non-formal training, micro-credentials and larger credentials is an active area of research. In a recent systematic review of the literature on micro-credentials, three-quarters of the studies explored the integration of micro-credentials into the curriculum (Tamoliune, 2023). What’s more, the review reported that half of the studies published between 2015 and 2022 explored the stackability of credits and qualifications and the role of PLAR. In other words, this is a rapidly evolving field. There are no clear standards and practices; most institutions are experimenting with ways to facilitate the process that makes sense in their context.

Relationship Between Micro-credentials and Larger Programs

The relationship between micro-credentials and larger programs like diplomas, certificates, and degrees deserves its own exploration. Often, micro-credentials are thought of as separate from these traditional offerings. However, micro-credentials can serve as on-ramps to larger credentials, can supplement them, and can help alumni maintain their professional edge.

Micro-credentials and larger credentials provide distinct benefits to learners. Micro-credentials are viewed as more achievable and less daunting. They allow learners to build their credential portfolio, and with it, confidence in their abilities. If life events interrupt a learner’s studies, the modular nature of micro-credentials ensures that learners still receive recognition for the accomplishments they have achieved so far. This differs from larger programs where failing to complete just one course results in no recognition of the learner’s achievements (Hope, 2022; Perea, 2020).

Conversely, degrees are more established, better known, and better recognized by employers. They represent a sustained level of engagement with a topic, and therefore depth of learning and expertise. Their development focuses on quality, and while they can be slow to respond to community needs, this approach ensures that they focus on sustained needs rather than follow ephemeral trends. This stability helps these larger programs become reputable.

Combining micro-credentials and larger programs maximizes the benefits of both. There is more than one way in which micro-credentials can complement a macro-credential such as a degree. Some of the connections include:

- On-ramps. Micro-credentials can prepare learners for a larger academic program without necessarily laddering into it. For example, a micro-credential can provide a “taste” of the larger program to help learners decide whether the larger program is the right one for them. Alternatively, it may help a learner acquire some of the knowledge or competencies they need to apply to a larger program, such as opportunities to build an artist’s portfolio before applying to a Bachelor of Fine Arts program.

- Laddering, PLAR, credit bank. Micro-credentials can also serve to give learners advanced standing if they choose to continue in the larger program. By completing the micro-credential, the learner acquires many of the same skills and knowledge as they would in the larger program, and the institution recognizes this by awarding credits toward the larger program. This can be done through laddering (if the micro-credential is credit-bearing), or through PLAR or credit-bank arrangements (if the micro-credential is non-credit bearing). This allows learners to give a topic a try, with minimal risk. If it’s not right for them, the learner loses only a small amount of time and money (less than the full program), and they leave with some credential recognizing their learning. If it is right for them, their short-term investment is not wasted, since the educational pathways recognize their completed micro-credential toward the pursuit of the larger program. See BCIT Ladders Micro-credentials into Associate Certificate for an example.

- Micro-credentials embedded in a larger credential. Micro-credentials, as small units of applied learning, can complement the learning that takes place during a larger program. There are several ways in which this may be done. Micro-credentials can use industry certification programs to give learners work-ready skills that employers recognize, such as a software certification (McCaffery et al., 2020). A micro-credential can serve to articulate and recognize individual skills learned as part of a larger course (Cook, 2021). This could be important to convey if employers want to know about a person’s ability to competently perform some of these skills. See Role of Competency-based Education in Undergraduate Courses for more details about this option. Micro-credentials can also offer different options and learning journeys resulting in different skillsets as part of a larger program (Cook, 2021). Micro-credentials can serve to recognize the different applied skillset chosen by each learner, despite each receiving the same macro-credential. See UBCO Embeds Micro-credentials in a Freshmen BFA Course for an example of this practice. Another example with similar aims (presenting options for undergraduates) is provided in the chapter Campus Collaborations in the section UFV’s Partnership Between the College of Arts and Continuing Education.

- Post-graduate micro-credentials. Finally, micro-credentials offered to alumni of a larger academic program can serve several purposes. It can be a way to foster lifelong learning and support graduates in maintaining their professional knowledge, develop their expertise, and update their knowledge of emerging trends in their field. It can also be a way to make further education accessible for working professionals. For example, a post-graduate micro-credential could be recognized for advanced placement into a graduate program.

Figure 2 shows the different ways to connect micro-credentials and macro-credentials (particularly a degree).

Incremental credentialing (sometimes called “Credential As You Go”) is an idea that is gaining traction in some circles. It proposes that a degree can be “unbundled” into smaller chunks (micro-credentials) that learners can complete separately and then combine to earn the degree. In 2021, David Leaser, an executive at IBM, co-authored an article where he outlined eight benefits of this practice from an employer’s point of view (Leaser & Zanville, 2021). He explains that this approach to obtaining a degree helps people enter the job market and get experience faster than traditional degree programs. This can ensure that they do not invest four years in a degree only to realize once they enter the workplace that it is not for them. It also gives them remuneration since they are working while going to school and this can help to pay for further education. Leaser & Zanville argue that smaller credentials are easier for employers to interpret, making it easier to align a prospective candidate’s qualifications with the requirements of a job. It makes learning more accessible to diverse learners and, in doing so, broadens the diversity of people in some fields. It provides just-in-time learning, when people are more likely to recognize the value and need for the learning, and therefore increases their motivation to learn. It also fosters a culture of lifelong learning, since workers continually return to education throughout their career.

Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition

Learning can happen in many contexts. It can occur in a school or post-secondary institution, but it can also happen “on the job” through hard-earned experience or through educational opportunities that do not result in credit-bearing recognition. It’s worth disambiguating these different types of learning (Johnson & Majewska, 2022; OECD, n.d.).

- Formal learning is learning that takes place in an organized and structured fashion, guided by explicitly stated learning outcomes, which usually takes place in a course at a school or post-secondary institution. Formal learning is recognized by these institutions through credits and leads to formal recognition of qualifications (e.g., a diploma, certificate, or degree).

- Informal learning is learning that happens throughout life, outside of the classroom environment. It occurs without having a structured plan or even intentional goals. Examples include visiting a museum, reading information in a book, magazine, or online, talking to others, being mentored to do a task, attending talks and conferences, watching videos, or doing background research to be able to accomplish a task at work. The learning is unorganized and does not have explicit learning outcomes, yet it results in the growth of knowledge and abilities.

- Non-formal learning is somewhere in between formal and informal learning. The learning can be somewhat structured and have learning outcomes, but they are softer, often not assessed, and not recognized in academic environments with credits. This includes taking a workshop offered by your local library, completing a non-credit continuing education course, registering for a massive open online course (MOOC), participating in professional development training at work, etc.

Prior learning assessment and recognition (PLAR) is a way to forge pathways between informal or non-formal education (i.e., non-credit) and formal (i.e., credit) education. It’s a way to translate the experience and knowledge that adult learners have gained outside of a post-secondary institution and to formally recognize their equivalency in an academic setting.

In the context of micro-credentials, there are two ways in which PLAR can come into play:

- To facilitate the recognition of the learning achieved as part of a non-credit micro-credential and count it toward the completion of an academic (for-credit) program.

- To recognize work experience, or other non-formal or informal learning, and count it toward the completion of a credit-bearing micro-credential.

Good PLAR processes ensure that the outcomes are academically defensible and trusted. See the section Brief History of PLAR and the Credit Bank in B.C. for information on the three pillars of a good PLAR system (transparency, consistency, and rigour).

In B.C., PLAR is practiced at the institutional level. The institution sets its own policies and processes for what evidence it will collect and review, what criteria it will use to analyze that data, who will evaluate it, and what are the possible outcomes.

As described in the section TRU’s Experience with PLAR, a 2019 survey of B.C. post-secondary institutions conducted by the B.C. Prior Learning Action Network (BCPLAN) finds that institutions vary widely in their existing knowledge and resources to support PLAR. That same survey also found that PLAR is an active area of development, with most institutions expanding their activities and resources in this realm.

Finding ways to link non-credit and credit experiences is proving to be one of the toughest challenges to solve for micro-credentials, with 76 per cent of respondents at 190 North American schools of continuing education indicating that institutional barriers to such translations are the greatest hurdle (Modern Campus, 2023).

Note that PLAR does not have to be done at the institutional level. PLAR could be done by an outside organization that uses a robust PLAR process to review common experiences that learners are likely to request for PLAR, such as professional development training offered by government departments, the military, and non-profit organizations, as well as massive open online courses (MOOCs). The organization could then make a recommendation for PLAR credits for each program, which institutions would be free to accept or ignore. This approach would reduce the duplication of effort across the system, ensure that all institutions have access to PLAR even if they do not have in-house resources, provide consistency and transparency for learners about their PLAR opportunities, and enable system-wide transferability of informal experiences into academic programs.

In the United States, the American Council on Education (ACE) provides such a PLAR service. ACE reviews common informal educational experiences using a transparent, consistent, and rigorous process. Educational experiences deemed worthy of academic credit are included in the ACE National Guide, which serves as a database of credit recommendations for institutions. Institutions have the option to accept or disregard the recommendations provided by ACE.

The Suggested Resources section contains references to numerous articles and reports on PLAR and its best practices, including a proposed national framework.

Credit Bank

As may have been inferred from the previous section, PLAR can be practiced at two levels:

- Individual learner, where each learner provides detailed evidence of their prior learning, which the institution reviews. This is the most common type of PLAR practiced at B.C. post-secondary institutions.

- Pre-assessed program, where common non-formal learning experiences are assessed by the institution to determine whether they are eligible for PLAR credit. This is then made public so that learners can know, ahead of time, whether their experiences will be given credit. This form of PLAR does not require individual learner assessment; if a learner provides evidence that they have successfully completed the training, they are automatically granted credits. Such a PLAR system is called a credit bank. Thompson Rivers University (TRU) has maintained such a database for over a decade.

For information about the inception of the TRU credit bank, see the section Brief History of PLAR and the Credit Bank in B.C.

For information about how the TRU credit bank operates and about a pilot project aimed at establishing a province-wide credit bank for micro-credentials, see the section TRU’s Experience with the Credit Bank .

Direct Assessment

Direct assessment is like a challenge examination but is used to demonstrate competencies. In competency-based education models, what matters is not how long a person spent learning a skill in a formal educational setting (or indeed where they learned the skill), but rather that they have mastered and can demonstrate those skills (Brower, 2014). A person could conceivably take a course, skip the training, and go straight to the assessment. If they can demonstrate their abilities at the level required for the course, they pass the course.

Taking this idea further, a question to consider is whether learners need to register in a course at all. What if they are confident that they can demonstrate the skills for a course and need the certification, perhaps as a requirement for hiring or promotion or because their formal credentials are from another country and they are having a difficult time having those credentials recognized by employers in Canada. Should learners spend time in a course when they know they are prepared to take the assessment?

That’s the idea behind direct assessment. Adult learners skip the course and go straight to the assessment. If they are successful, they earn the micro-credential. This micro-credential is identical to the one earned by learners who took the course. In these situations, the post-secondary institution is not a content provider (i.e., a provider of learning), but rather an assessor and certifier of qualifications and competencies (ContactNorth, 2016).

The Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) is a leading innovator of this form of assessment and credentialing pathway in Canada. See the section NAIT Innovates with Direct Assessment to Offer Micro-credentials for a fuller description of their work.

Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector

KPU’s Approach to Micro-credential Laddering

David Burns is associate vice president academic at Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). He was involved in the development of his institution’s policy governing micro-credentials. Below, he shares his thoughts on the importance of balancing flexible pathways for learners and creating coherent educational pathways.

Interview

What is at stake in creating new educational pathways for learners with micro-credentials?

“One of the challenges of micro-credentials is the potential for accidental change. Let us say, for example, that a learner completes a series of micro-credentials dealing with discrete, short-term learning outcomes. Suppose also that we establish a credit system for micro-credentials that allows these to add up to substantial credit. Those credits are transferable and, to the extent the program ladders or transfers, so too is the credential they would receive. This is, in value terms, great — we want flexible degree pathways and student choice.

“It is, at the same time, a way that programming can change in fundamental ways without anyone planning out that change to ensure it is responsible, coherent, sustainable, or in the interest of students. Like any new tool, micro-credentials are powerful and exciting to the extent we know how to use them.

“At KPU we want to use micro-credentials to open up possibilities for learners and make education more accessible. The most meaningful innovation will be found in using micro-credentials to challenge how we think about other credentials, and in challenging micro-credentials to meet the high standards of the rest of our programming.

“It isn’t yet clear whether we can use these tools to change how we think about post-secondary education. It is clear that we need to try, and that our efforts to do so need to embody both our ambition and our responsibility.”

BCIT Ladders Micro-credentials into Associate Certificate

The British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) developed a micro-credential with the intention to ladder the training into a larger program. Laurie Therrien, manager of corporate training and industry services in the school of construction and the environment, shares how she built a new micro-credential in Introductory Studies in Mass Timber Construction while keeping laddering in mind.

Interview

Describe how your micro-credential ladders into other BCIT offerings.

“When we consulted with the mass timber industry about their educational needs, we learned that they wanted two things. They wanted a general introduction to mass timber, which we developed into the micro-credential in Introductory Studies in Mass Timber Construction. They also wanted to train workers in a specialized area of mass timber, which is assembling. Mass timber is a maturing industry and companies can’t find workers with this training since there is no formal program for it. We developed an Associate Certificate in Construction of Mass Timber Structures to address that gap.

“In effect, the two programs – the micro-credential and the associate certificate – were planned at the same time. I had a progressive credentialing model in my mind, where we started with the design and launch of the micro-credential and, if that was successful, then we would build from there. Once the micro-credential was offered, industry confirmed that they needed more training. The idea for the associate certificate was there from the beginning, but we built it in a staged fashion.

“We built the associate certificate so that part of it overlapped with the micro-credential. Courses in both programs have gone through quality approval at our institution and have credits attached to them. It was therefore relatively easy to work out a pathway where people who have taken the micro-credential get 2.5 credits toward their 15 credits required for the Associate Certificate in Construction of Mass Timber Structures.

“It’s to the benefit of learners. We tell them, ‘if you’re not sure if you want to do the associate certificate, take the micro-credential, and if you enjoy it, then apply for the associate certificate.’ It’s less daunting, there is less risk for them. It gives them a taste. If they decide to pursue the larger program, it gives them a discount on tuition and they start the program with advanced standing.”

Do learners take advantage of this educational pathway?

“The associate certificate is new — we piloted it last year and we have just completed the first post-pilot offering. We have had 41 people register in the program. Out of those, I would say probably 30 of them had done the micro-credential. The micro-credential is a huge feeder pool for the associate certificate.”

Role of Competency-based Education in Undergraduate Courses

David Burns is associate vice president academic at Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU). He is a strong advocate of competency-based education. He shares some of his thoughts on the opportunities that micro-credentials represent for undergraduate learners.

Interview

How might micro-credentials supplement undergraduate education?

“I anticipate that micro-credentials will be very helpful for students in certain disciplines. Consider a student enrolled in a health care program. Right now, if they take Health 201, they get a transcript that says that they passed Health 201. But imagine a situation where there are 12 fine-grained performances that students are expected to master in this course. Say one of them is the ability to make an arm splint. Once a student has demonstrated the ability to do an arm splint, they earn the micro-credential for it. What happens now is that by the time the student finishes the course, in addition to a transcript that says that they passed Health 201 with a B+, they have an official record (perhaps captured in a series of digital badges) of the performances or competencies they have mastered and demonstrated that they can do. The health system could utilize that kind of granular information to hire the right candidate for a role. It’s almost like certifying that the student has successfully mastered individual learning outcomes from the course.

“It won’t work for every course or discipline, but there are all kinds of discrete performance outcomes that will work. It works well in something like health care where you have dozens and dozens of fine-grained performances you need to master. You can imagine that this recognition of individual skills would allow students to articulate their achievements more precisely.

“Arguably, this could be a more rigorous way to capture achievements. At the moment, when a student gets a grade of B+ in a course, they may have failed some components of the course and done really well on others. The B+ on their transcript doesn’t reveal that. A B+ is an abstract concept created by blending lots of different assignments. An employer may not care about a graduate’s ability to do most of these things. They just want to know that a potential hire can do something like regression analysis or making an arm splint. Recognizing each skill or learning outcome in a course with a micro-credential or badge will give a fine-grained picture of what the student can and cannot do after taking a course.”

UBCO Embeds Micro-credentials in a Freshmen BFA Course

Myron Campbell is associate professor of teaching in creative studies, media studies, and visual arts at the University of British Columbia Okanagan campus (UBCO). He has embedded digital badges into his first-year course that recognize the skills that students develop as part of their term project. Below, he explains the nature of his innovation.

Interview

Your undergraduate students are awarded digital badges as part of their coursework. Tell us about it.

“Students enrolled in the Bachelor of Media Studies and the Bachelor of Fine Arts must take Introduction to Digital Media in their first year. In this course, students learn to use digital tools to create visual media such as videos and 3D animations.

“In the lecture portion of the course, all students are exposed to the same curriculum. This includes things like how to take a project from ideation to completion, as well as foundations of composition and colour theory.

“Students also meet with their teaching assistant in smaller groups for studio time, which is a computer lab. This is where their educational journeys branch off. There are eight specializations for students to choose from. Students may focus on digital design, video production, visual effects, 2D animation, 3D animation, experimental moving image, computational art, or a generalist stream. Their choice sends them down a different curriculum path for the studio portion of the course. Each curriculum is offered online on the Canvas LMS. Students learn the basics of a digital tool and then use the tool to create their term project.

“While each stream teaches students different digital tools and skills, some of the skills are common across streams. For example, most streams require students to create sound as part of their project. For one stream it might be atmospheric sounds while for another it might be recorded dialogue for a film. To maximize the opportunities for student interactions and peer learning across projects, I lined up the project deliverables so that similar aspects of the project, requiring similar skills like sound are due at the same time during the semester. Students largely proceed at their own pace, but they must submit their work on these due dates, so that their work can be critiqued by peers. There are four such deliverables throughout their project.

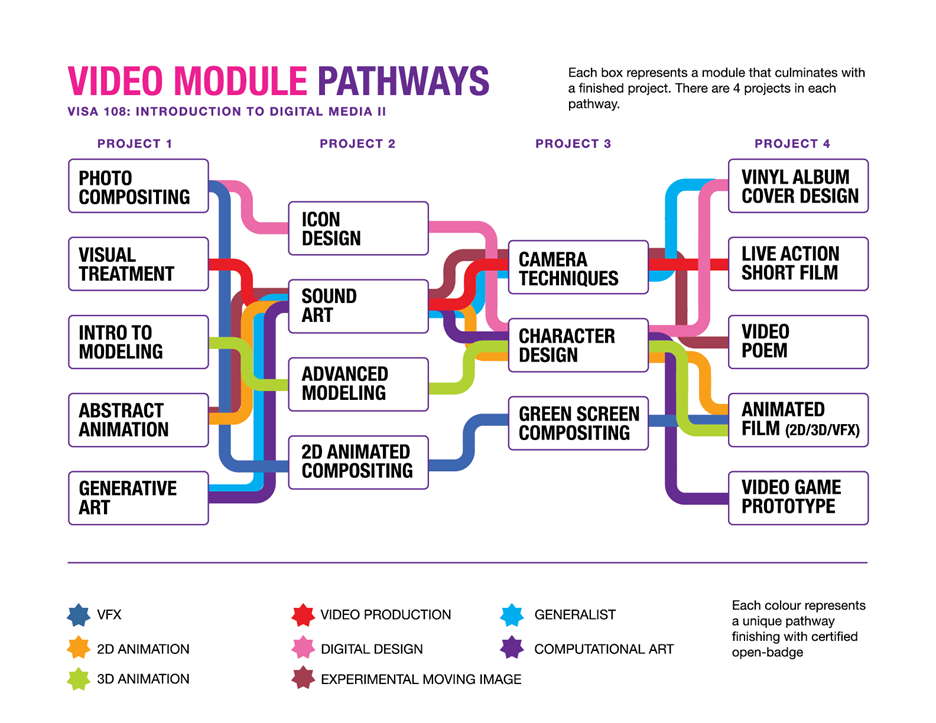

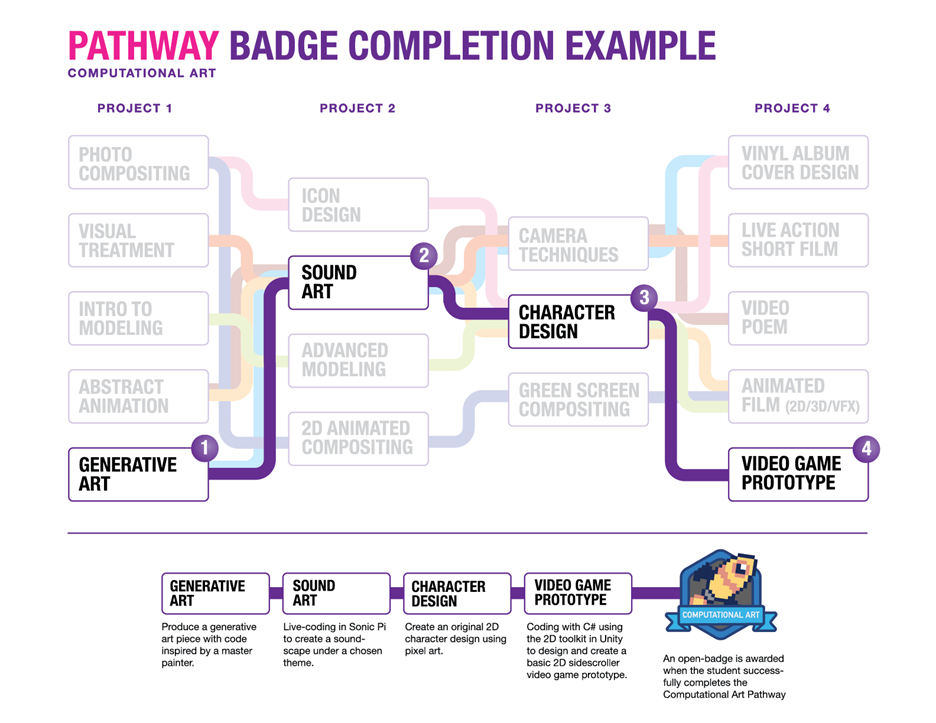

“I created a visual capture of the different streams and their deliverables. It looks like a complex London Underground system where the streams meet up at some of the common deliverables (see Figures 3 and 4).”

How is the completion of the projects recognized?

“Once a student successfully completes the course, they receive a grade on their transcript. They also receive a digital badge that provides a fuller description of the specific skills they applied and demonstrated as part of their specialization. There are eight different badges. The badges are awarded by the centre for teaching and learning and are validated as official UBCO digital badges. In this way, students leave the course with a recognition of the skillsets they developed, which could be different to those of their peers. These digital badges can be used in job searches because they provide more detailed information about what the student can do than a transcript.”

Why did you create this curriculum model?

“One of the challenges that I faced as an instructor in this course is that students come in with varied backgrounds. Some already know how to use Adobe Photoshop, others know how to do music editing, and others have some 2D animation experience. With a set curriculum, I found it difficult to cater to all backgrounds.

“I also wanted to give them an opportunity to explore a career of interest, as part of their first-year experience. The freshmen curriculum can be quite general and does not provide many opportunities to pursue hands-on experience in a discipline of interest.

“The thing about these tools is that once you learn to use one, you develop a digital literacy that transfers to using other tools. In a way, it does not matter which tool we teach them, because they develop digital literacy and learn to find solutions when they encounter problems. This is a transferable skill in our industry.”

What have been some of the successes in this program?

“Giving students agency over their learning is motivating. They invest themselves and create outstanding projects. They love it. When I first started doing this, I feared that some students might want to switch halfway through a specialization. So far, there have only been three students out of about 150 that have chosen to do so, and all request to transfer have occurred before the first deliverable. Students commit to their specialization because it was their choice.

“I am upfront with them from the beginning that some streams require more work than others. It’s the nature of the different fields. I expected that students might complain about the imbalance of it, but that never happened. Again, I think it’s because they have agency in selecting their specialization, and it allows them to choose the level of difficulty that’s right for them.”

What have been some of the challenges?

“As you can imagine, this is a lot of upfront work for the course designer — I am effectively designing several different courses.

“The other challenge has been integrating this into Canvas, our LMS. Once a student selects a specialization, we have to manually load it into Canvas for the student. We found a workaround but it is not the most elegant solution. Canvas was not set up for this.”

What comes next?

“There are a few things that we want to explore. For example, a student could conceivably want to re-take the course and pursue a different specialization. At the moment, the degree requirements would not allow a student to do this.

“We are exploring exporting this component of the course to an outside audience, to offer it as a micro-credential. Nothing would need to be changed, including the online course materials and the digital badges used to recognize the demonstrated skills. It’s already a micro-credential that’s embedded in a first-year undergraduate course.”

Image source: Myron Campbell, UBCO.

Brief History of PLAR and the Credit Bank in B.C.

Don Poirier is associate vice president of open learning at Thompson Rivers University. He joined TRU in 2007, shortly after it was established and it was given the responsibility for open learning in the province. Below, he shares his recollections of the credit bank’s inception and how TRU became a leader in PLAR, as well as recommendations for ensuring that PLAR is trusted at an institution and in the system.

Interview

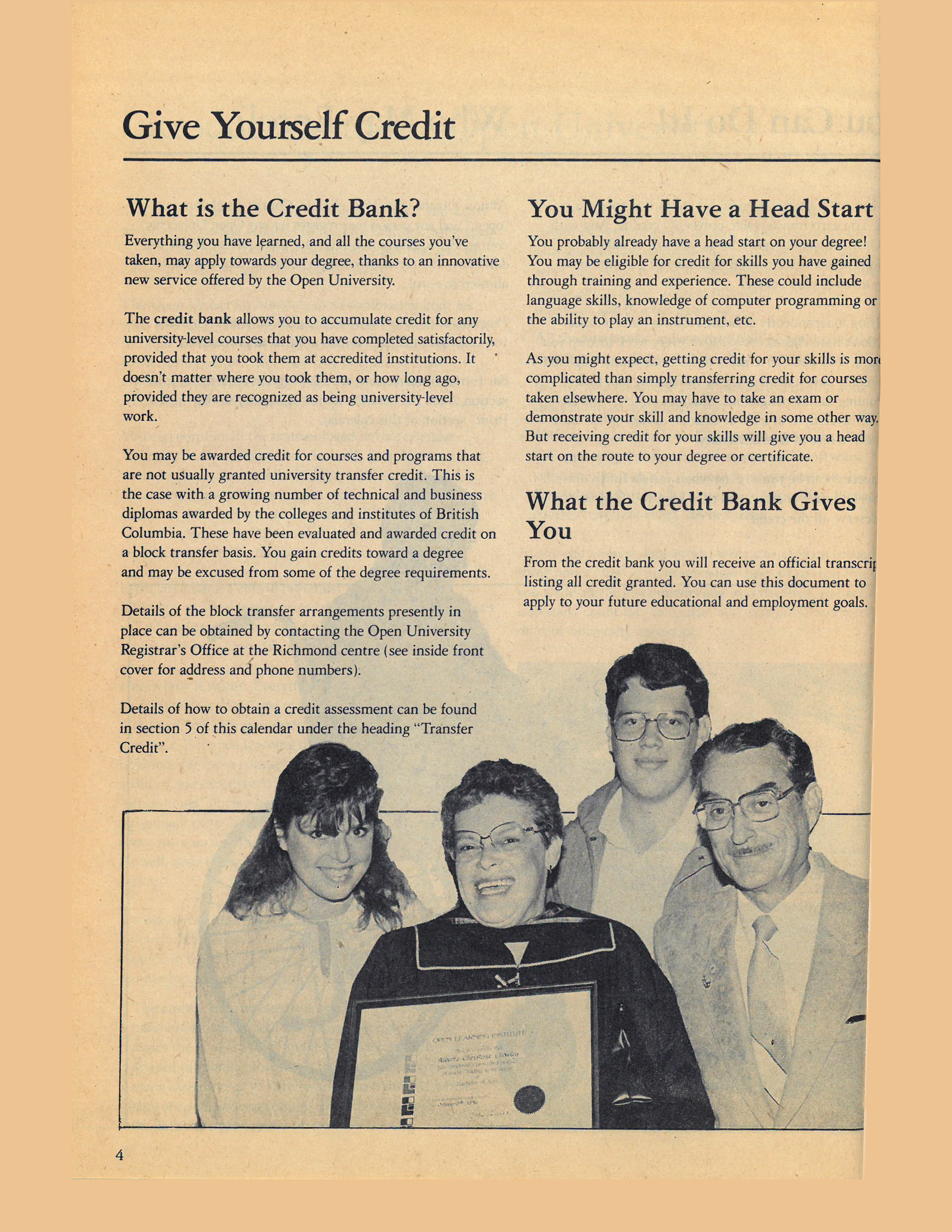

What is the history of the credit bank?

“Between 1978 and 2005, B.C. had an open learning post-secondary institution that delivered distance education. Its name changed over time, but most people today remember it as the British Columbia Open University (BCOU). Government leaders realized that the geography of this province. — with mountain chains and many island communities — could present a challenge for people to access post-secondary education. If people couldn’t travel easily to education, the government would bring education to them, through distance education. Open learning was initially about economic and community development.

“In time, open access evolved into a broader concept. BCOU recognized that adult learners had often taken courses at other institutions, and they wanted this learning validated. This was at a time when each institution was siloed from the others and before the creation of the B.C. Council on Admissions & Transfers (BCCAT). In effect, open access started to address credit transfer within the B.C. post-secondary system and facilitated it for learners. By recognizing learning that took place at other B.C. post-secondary institutions and by awarding credit on a BCOU transcript for it (which could be used towards the completion of a BCOU degree), BCOU made post-secondary education more accessible for adults.

“This was the birth of the credit bank, as it was defined then. I have a picture of the BCOU calendar from the 1988-89 year that describes the credit bank (Figure 5). The idea was that you can take these bits of learning from other B.C. public institutions and perhaps even other providers and put them in your educational ‘bank account’ and apply them toward your credential at BCOU. It’s like someone’s individual savings account at the bank. You accumulate learning from formal or informal sources and experiences, and you bank them, to use them when you make a big purchase — in this case your degree or credential.

“In 2005, Thompson Rivers University (TRU) was created and assumed responsibility for open learning in British Columbia. The Thompson Rivers University Act legislates that TRU will be responsible for promoting it and to ‘serve the open learning needs of British Columbia.’

“What does that mean? You may have picked up that the original concept of the credit bank was about two things: transfer credits (for courses offered at other B.C. post-secondary institutions) and PLAR (for informal experiences and courses taken outside of the B.C. post-secondary system). BCCAT was created in 1989, and by the time TRU took over the mandate for open education, BCCAT was working well to manage the transfer credit system in B.C. The credit bank couldn’t be about transfer credit, as it would only duplicate BCCAT’s efforts. That left PLAR.

“That’s the focus that TRU adopted in continuing to develop the credit bank. The TRU credit bank is now focused on nonformal training.”

What are important elements of a well functioning PLAR system?

“In the past, PLAR was a four-letter word for some people. It was mistrusted. That’s because some people feared that it was not a rigorous process — that the decisions were based on the whims of a person. But that’s not what PLAR is.

“PLAR is an exercise in translation. You translate learning that took place outside of the B.C. post-secondary system into something that you recognize as equivalent in the B.C. post-secondary system. To do this, you need to accumulate proof. PLAR is proof. That proof needs to be defensible — academically defensible. You need evidence that meets the requirements of the post-secondary system.

“To achieve trust in PLAR, there are three necessary ingredients.

“First, the PLAR process must be transparent. How is this exercise in translation being done? What is being evaluated? Who is evaluating it? By what criteria? This information needs to be made available to anyone in the system who wants to see it. It demystifies the process.

“The second ingredient is consistency. The way in which the assessment is being done, and the judgment that results from it, should be the same today as it will be a week from now. It cannot be because the assessor was feeling good that day or because they liked the students who requested a PLAR assessment. It needs to result in a predictable and repeatable outcome.

“Finally, the process must have rigour. It is about documenting evidence. It is about following a detailed and defensible process. This is the responsibility of a PLAR director. This person does not have the authority for making the final (academic) decision on a PLAR evaluation. Rather, they are responsible for building a robust process for collecting evidence, for determining who will evaluate the evidence, and the criteria by which they will reach a decision. They are responsible for quality assurance.

“These three ingredients — transparency, consistency, and rigour — instill understanding, trust, and ultimately acceptance in the final PLAR decision.

“Within a North American context, the American Council on Education (ACE) and their credit recommendation service is the gold standard for PLAR of non-credit training. They have an established list of criteria that they use when reviewing a program for PLAR credit recommendation. They have been doing PLAR assessment for over 100 years. Dozens, if not 100s of institutions, accept their recommendations for credit. That’s because their processes are transparent, consistent, and rigorous. At TRU, we built our processes for our credit bank based on the ACE processes.”

Top Tips for Building a Trusted PLAR Process

- Make it transparent. Ensure transparency in the review process and criteria by making them accessible to the academic community, both in general and for each individual evaluation.

- Make is consistent. Ensure that the process is repeatable and that reviewers have clear sets of standards to use when reviewing a program.

- Make it rigorous. Develop a process that collects the right set of data to make an informed decision and document the evidence for every review. This is the quality assurance piece.

TRU’s Experience with PLAR

Susan Forseille is director of prior learning and assessment recognition (PLAR) at Thompson Rivers University (TRU). She is also the chair of the board of directors of the British Columbia’s Prior Learning Action Network (BCPLAN), a network of organizations that promotes increased access to B.C. post-secondary credentials through informed recognition of adults’ past experiences, as well as a member of the board of the Canadian Association for Prior Learning Assessment (CAPLA). She is currently completing her PhD on the impacts of PLAR on career development. Below, she shares her knowledge about the state of PLAR in B.C. and the process TRU developed to support adult learners.

Interview

How do you define PLAR?

“PLAR stands for prior learning assessment and recognition. It is a process used to evaluate and recognize the knowledge, skills, and abilities that a person has acquired outside of post-secondary education. The PLAR process involves assessing a student’s previous learning experiences such as work, volunteer, and/or self-directed study, to determine if they meet the requirements for academic credits or recognition.”

Why is there renewed interest in PLAR?

“When I first started in PLAR I was told that in the 1990s, institutions received funding to develop PLAR from the provincial government. This funding stimulated innovation and interest in recognizing the prior learning that adults bring to their studies, However, when the funding stopped, institutions turned to other priorities. In the past few years there has been another growth of interest of PLAR.

“I think the revived interest that we are observing comes primarily from two sources. The first is the labour market. The labour market has never changed as rapidly as it is changing right now, nor has it ever been as unpredictable. We are seeing larger changes than during the post World War II era. The profound restructuring of the labour forces is not just a result of the pandemic, it is from the demographic changes we are going through. Currently in Canada there are over a million vacant positions. As our population ages we don’t have enough people of working age to fill these positions, and projections are that the continued aging of our population will see increasing struggles to fill positions.

“Compounding this is the quickly changing skillset needed for the emerging labour market. This is being fueled by advances in technology, the need for more health care professionals, and climate change. Another level of complexity is how individuals view their careers. We have seen significant changes in our career expectations. We have moved from work being seen primarily as a means to a pay cheque to increasingly also desiring fulfilment, the need to make a difference, and enhanced work-life balance.

“These changes in the labour market, and our career expectations, are fueling a need for career resiliency. This means that we must give workers the tools to upskill and retool quickly. Large corporations are very aware of this. For example, Google has created Google Career Certificates and IBM SkillsBuild plans to have 30 million learners go through their platform by 2030. These are examples of employers providing the specific skills and knowledge they need to maintain and/or grow their businesses. They are no longer relying on hiring recent graduates from post-secondary institutions. This is also an example of employers providing just-in-time delivery of specific learning they require and an understanding that this learning is life wide and long, no longer predominantly at the beginning of one’s adult life.

“The second reason there is revived interest in PLAR is more pragmatic. Many B.C. institutions are struggling with domestic enrollment rates. The group that we are struggling to attract the most are adult learners. At the same time, there is an increase in adult learners wanting to reskill, upskill, or have their non-formal and informal learning assessed for possible credit and recognition. We need to build more on-ramps for these learners to make post-secondary education more accessible for them. This will help institutions meet their enrollment targets, but just as importantly, create a more equitable and diverse post-secondary system.”

What are the benefits of devoting resources to PLAR for learners and for the institution?

“There’s the obvious answer that earning credit for prior informal and non-formal learning allows a learner to complete a program faster. We have clear data – from TRU and from the study of 230,000 adult learners in the USA — that when learners receive PLAR credit, they have increased completion rates compared to other learners and they tend to earn higher GPAs. There is also growing research that PLAR students are quite successful in other ways. I think it is because when learners receive credits for their experience, it makes them feel validated and valued. It increases their sense of self-efficacy and self-worth and this positively impacts their career development and life in general.

“The benefit for institutions is also strong. PLAR creates accessible pathways for non-traditional learners into post-secondary education. This promotes equity for all learners, and it recognizes and values diversity. It’s a way to practice what we often say we value in our institutions. More pragmatically, it’s a way to attract new learners. Since PLAR credits count toward the institution’s full-time equivalency (FTE), it can also help to meet enrollment targets. And, since these students typically have greater completion rates, it’s a way to address program attrition.”

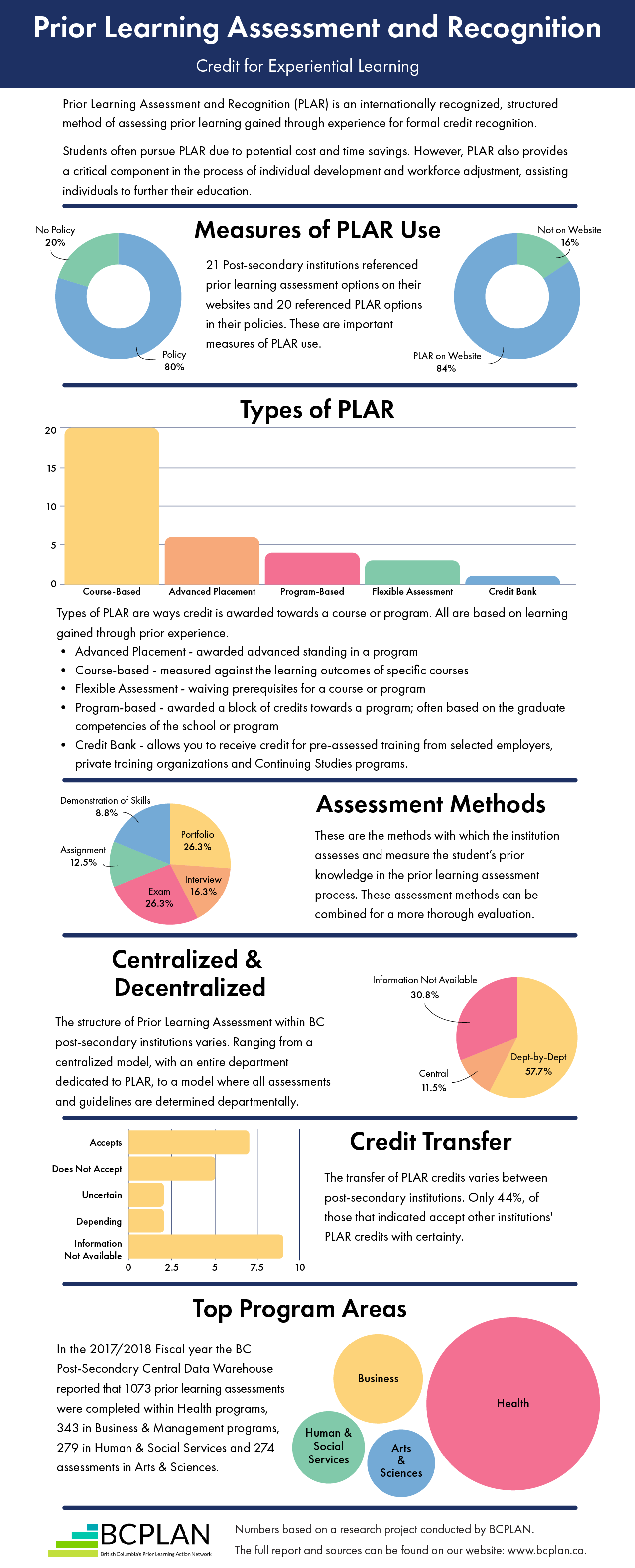

What is the current state of PLAR in British Columbia?

“In 2019, BCPLAN received funding from the British Columbia Council on Admissions & Transfer (BCCAT) to investigate the current state of PLAR at 25 B.C. post-secondary institutions. BCPLAN made the full report and the findings about each institution available on their website. You can also watch a 12-minute overview of the key findings. I’ll provide an infographics summarizing the findings below (Figure 6).

“What we discovered is that many schools are looking to get into the space. In fact, 15 of the 25 institutions had shown growth in the development and allocation of resources for PLAR. That said, it is still not a well-developed area, with many institutions still offering PLAR ‘off the side of staff’s desks.’ In comparison, TRU has had a dedicated PLAR department since 2007. The College of the Rockies and North Island College also have PLAR offices. KPU and Camosun are in the process of setting up an office. RRU, VCC, and UFV have at least one person assigned to PLAR. UBCO just formed a committee to explore PLAR.”

Who are the exemplars for PLAR that institutions can look to as they develop their own approaches?

“One of the most common questions we get at BCPLAN and at CAPLA is how to set up PLAR at an institution. These two organizations’ websites provide a ton of resources to begin their research. The other advice I would have is to look at proven practice — what others who have engaged in this have learned through experience.

“PLAR is currently in a state of rapid development. There are pockets of good practice throughout B.C. and Canada. However, there is no government oversight and no recognized standards. It feels like we are in the beginning stages of innovation.

“One of the better developed systems is in Quebec. All Collèges d’enseignement général et professionel (CEGEP) obtain their policies and tools for engaging in PLAR through a central organization (funded by the government) called the Centre of Expertise for the Recognition of Acquired Competencies (CERAC) [note that the linked website is in French]. All CEGEPs use the same system for PLAR. This benefits learners because they can feel confident that if one school recognizes their experience, it will be recognized across the system. The funding model is also different. When a student applies for PLAR and enters the process, the institution receives a certain amount from the province to engage with the learner in the process. About halfway through, more funds are released. Once a learner completes the PLAR process, the institution receives the whole amount. As a result of this model, there is an incentive for institutions to offer PLAR, to support learners throughout the PLAR process, and to do it well.

“The other exemplar is Ireland. Ireland is also faced with a growing labour shortage. The country needs to help people acquire the training they need rapidly to fill skilled jobs. They are working on a national framework for PLAR, including developing national policies. The government is providing resources to support inter-institutional conversations and ensure that the agreed upon solution will satisfy all institutions and that it is rigorous. The organization that they contracted to lead the project is called the Technological Higher Education Association and their website is full of links and resources to the project.

“Another exemplar, guiding much of our PLAR processes at TRU — our values, philosophy, and tools — is the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL). They conduct a lot of research and it’s a valued go-to resource for information on PLAR.

“The tool that we use for our credit bank, which I will talk about later, was inspired by the American Council on Education (ACE). ACE has developed rigorous processes and tools to assess the merit of non-credit training for PLAR credit (they call the process ‘learning evaluations’). These non-credit trainings are programs like MOOCs offered by Coursera and online courses offered by Google Career Certificates and IBM SkillsBuilder. It conducts the assessments and has built a database over time. It makes its findings available as credit recommendation. In other words, institutions do not have to accept the PLAR credit for a certain training, but the institution can inform its decision on transparent information and recommendations that are trusted in the sector. This respects institutional autonomy while ensuring that institutions that do not have the resources to conduct PLAR assessments can access this service and data. It’s a gold standard in the PLAR field.”

How does TRU conduct a PLAR assessment? What’s involved?

“At TRU, we have been doing PLAR since 2007, so we have had the chance to test out a variety of approaches. We currently offer four PLAR pathways. I will describe each of them in turn.

“Challenge exam. This is probably the process that’s most familiar. It’s similar to the process used in professional organizations, where it does not matter where you took your training, everyone takes the same exam to show their knowledge and competencies. We don’t have challenge exams for every course, but we have many for our language courses.

“Competency-based. This is a personalized and labour intensive PLAR assessment designed around TRU’s Institutional Learning Outcomes. Learners develop a portfolio to document and show evidence of their ability to achieve a set of eight competencies. This can easily be four or five pages per competency, not including evidence of their learning claims. These portfolios can be over 80 pages. In the portfolio, the learner presents how they came to learn each competency. A PLAR advisor works with each student to guide them through the process. Two subject matter experts (faculty) assess the portfolio using a rubric. Sometimes, they may interview the learner to fill in the blanks. Everything is documented. This is typically only used for elective credits. Depending on the program, the rigour of their portfolio, and their prior learning, there is a wide range of credits that can be awarded, from six to as many as 75. A student could skip first and second year through this process, so it is worth their while. Few institutions are doing it — I think it’s just Athabasca University in Alberta, KPU, and TRU.

“Course-based. As the name implies, this is course-specific, with the course learning objectives guiding what is assessed. The instructor for the course decides what constitute evidence that the learner has met the course learning outcomes through other experiences. It could be a combination of examinations and portfolio. If it’s a portfolio, the instructor typically wants to see that the learner can weave theory through their applied experience. Sometimes it includes interviews, a demonstration of skills, letters of reference from employers, or learning journals.

“Credit bank. This is a database of educational programs that are not part of the BCCAT system (often they are non-credit training), whose programs we have rigorously evaluated and deemed to be equivalent to, and eligible for, TRU credits. We offer a listing of agreements on our website so current and potential students can quickly review who we have agreements with. About two thirds of our PLAR credits are awarded through the credit bank pathway. It’s a popular option for learners because it’s simple for them and it’s transparent.

“When a learner contacts us to inquire about PLAR, we discuss their prior experience and their goals, and we direct them to the most appropriate pathway.

How does PLAR work for Indigenous learners?

“TRU is deep into decolonization work. One of the areas that we have been exploring is how to do PLAR assessment in a way that recognizes Indigenous ways of knowing. In 2019, we completed a study asking whether Indigenous students felt safe including their Indigenous ways of knowing in their portfolio. Most said that they felt safe, but when I looked at the contents of their portfolios, I didn’t see much evidence of its inclusion, suggesting that there might be a gap.

“PLAR assessment is a very colonial process. It depends on written documentation. It is highly regulated. It also compartmentalizes learning and does not allow a learner to show their holistic integration of knowledge, a hallmark of Indigenous ways of knowing.

“We have been working with Indigenous communities to find paths for Indigenous learners to articulate what they know and how they know it. Elders and Knowledge Keepers have also shared with us that they want their traditional knowledge to be formally recognized by post-secondary institutions. We have been examining oral storytelling and holistic approaches to capturing knowledge.

“Recently we worked with an Indigenous student who was very knowledgeable and had the prior experience but he struggled to articulate it in a way that fit the existing PLAR structures. We asked him what might help him show us what he knows. He said that conversations were helpful. We considered this and considered also our requirement to document the evidence of his knowledge, providing an audit trail. In the end, he did three videos of his lived experiences. It showed him interacting with others in his work and demonstrating his abilities and knowledge in action. Also, instead of doing the compartmentalized PLAR approach of showing each competency individually, the videos showcased many integrated competencies. He supplemented the videos with a map showing when each of the competency was demonstrated in the video.

“It took dozens, perhaps even hundreds of hours to devise this decolonized PLAR process that fit his Indigenous ways of knowing and our need to document his knowledge. There were so many people that contributed their time, wisdom, insight, and knowledge into creating this path.

“Indigenous learners are not the only ones who will benefit from this decolonized work. We are taking what we have learned from this experience and other decolonization learning to build a more flexible PLAR process. Any learner who uses different modalities or ways of thinking or expressing themselves will have access to an opened-up PLAR process. We are grateful for the Indigenous student for being patient with us and teaching us how to do this. We still have much to do and learn, but we walked the path, and are still walking the path, together.”

Note: On June 7, 2023, TRU put out a press release, featuring interviews with Forseille and the Indigenous student mentioned above, describing the launch of a new Indigenized PLAR process at TRU.

Top Tips from TRU’s Experience in Setting Up a PLAR Process

- Develop policies to support PLAR. One of the reasons that PLAR is an efficient and effective process at TRU is because the roles, responsibilities, and steps have been clearly and transparently established through policies and procedures. Consider developing such governance-approved documents to ensure that the PLAR process is supported.

- Use top-down and bottom-up approaches. When creating a new PLAR process at an institution, consider using input from those who will be affected by it (e.g., faculty) as well as those who will administer it (e.g., senior leaders). The buy-in and support of both groups will be needed for the system to operate successfully.

- Explore what others have done. Talk to others who engage in PLAR to learn from their experience. Look not only for “best practices,” but also “proven practices.”

- Give yourself room for learning. Learn from your successes and mistakes. There will be mistakes; the key thing is to be transparent and to learn from them.

- Decolonize the PLAR process. Engage in conversation with Indigenous communities about ways to recognize the knowledge of Indigenous learners whose knowledge and processes may not easily conform to the PLAR process. How can you invite and recognize their learning and collect evidence of it? And how can you make what you learn from this modified PLAR process benefit all learners?

- Marketing and communication. PLAR is perhaps one of the best kept secrets in the province. Few members of the public know about it, yet many could benefit from it and it might even motivate them to return to education. A study at TRU found that 58 per cent of students who requested PLAR credit had learned about PLAR through their own research. Be sure to devote resources to let your current and prospective learners know of this opportunity to count their past experiences toward formal credit.

TRU’s Experience with the Credit Bank

Susan Forseille is director of prior learning and assessment recognition (PLAR) at Thompson Rivers University (TRU). In this role, she is responsible for administering the TRU credit bank. Below, she shares how TRU evaluates programs for the credit bank and talks about a pilot provincial credit bank for micro-credentials.

Interview

What is the credit bank?

“The credit bank is a type of PLAR. It is a database of educational programs that are not part of the BCCAT system (often they are non-credit training) that TRU has rigorously evaluated and deemed to be worthy of TRU credit.”

What programs are part of the credit bank?

“There are many training providers out there. Think, for example, of the training a person would get if they worked as a dental hygienist or massage therapist. Or of the management training they might receive if they worked for an insurance organization. Or, a First Nations group that is offering excellent training in band administration. Or, of the training received by completing the Canadian Association of Medical Radiology Technologist certification. Increasingly we have students asking about training offered through a MOOC on Coursera. These are all worthwhile training and we wanted to find a way to rigorously assess them and determine whether they might be recognized as PLAR credits.”

How does a program come to be in the credit bank?

“The process typically begins with the organization approaching us. For them, it can be an advantage to promote their program and say that upon successful completion, the program will ladder into a TRU Bachelor of Health, for example.

“Once we agree to review a provider’s training program, they pay a fee to cover the expenses of the review. This fee does not guarantee that their program will be awarded PLAR credit. We are upfront and transparent about this, and it is important to maintain the legitimacy and integrity of the process.”

Which aspects of these programs do you review?

“We have developed a tool, inspired by the American Council on Education (ACE) process. We ask to see what they are teaching. How are they teaching it? What is the textbook they use? Who are the teachers and what are their qualifications? We want to know how they are assessing the learning, because we want to have confidence that students are learning the content. How many hours are spent in the classroom? If there is a practicum, what does it look like? What is the feedback from learners? Is the program accredited? Does it grant PLAR for the program and, if so, how? We also want to know about learner outcomes. If there is a professional qualification exam, how are their students performing on this exam compared to students at other institutions? It’s a huge amount of information.

“As part of this review agreement, they agree to provide us with all the documentation and information that we request.”

Who conducts the review?

“We contract two subject matter experts to review the information. These are TRU faculty with subject matter expertise in the topic. If we do not have in-house expertise, we hire two TRU faculty to provide knowledge of TRU programs, TRU standards, and of our PLAR process, and another person, from outside of TRU, who is an academic and has expertise to review the content. Note that this review is not part of the faculty’s job description, so they do this for additional pay. It doesn’t pay a lot, and it can sometimes be a challenge to find faculty reviewers.

“The subject matter experts review all materials and they evaluate whether the training is equivalent to what TRU offers. They write a report. In it, they make a recommendation about the number of PLAR credits that should be awarded for the training, if any. They also make recommendations on the level of the credits (e.g., First year? Second year? Third year?), and the type of PLAR credit (e.g., block credit, equivalent to a specific course or courses? Applied study credit?).”

Once the SME recommend a program for PLAR credit, what happens next?

“The recommendations are first reviewed and approved by the dean of the appropriate unit, next by the registrar, then it goes to legal council, and finally to the provost.

“We draft and sign an articulated agreement with the provider. This is necessary because the legal document stipulates, for example, that if the provider changes the curriculum, we need to be alerted, and this could impact the PLAR credits. It’s one of our risk management processes.

“Once the articulated agreement is signed by both parties, the program is entered into our TRU credit bank. It’s basically a database of training programs that have been pre-approved for PLAR credit. If a student has completed one of these programs, in the timeframe where the agreement was in place (so that we have confidence that it was the program we assessed), then they can look up what sort of PLAR credits they are entitled to receive.

“Our credit bank assessment process is very rigorous. It must be trusted and defensible. Everything is documented, so that it provides an audit trail. This is important for quality assurance.”

Are there variations on the theme of how you conduct the credit bank review?

“Yes. This is the formal credit bank, which is what I have described so far. Then, there is also an informal credit bank. Let’s say a student comes to us and they have done paramedics training in the Armed Forces. We do not have a formal agreement with the Armed Forces for this program.

“What we might do, if we have the resources, is a modified ‘credit bank-like’ review. We ask the learner to assemble all the resources that we normally would request during a credit bank assessment. Only one subject matter expert reviews it. If they approve the training for PLAR credit, a dean or dean designate reviews and approves it, and the student receives PLAR credit.

“In this case, because the arrangement is with the student and not the organization, the student pays a modest fee for the assessment (rather than the organization in the case of a true credit bank assessment). It does not cover the costs of the review, but it discourages frivolous requests.

“For the next three years, we keep that information in our informal credit bank files, meaning that if another student comes to us with that training, we automatically grant them the PLAR credits. They do not need to collect all of the information and undergo another program review.”

What’s the connection between the credit bank and micro-credentials?

“Micro-credentials represent an interesting space to explore for the credit bank. Micro-credentials are subject to their institution’s quality assurance processes, but they are not part of the BCCAT transfer system. They fit the criteria for inclusion in the credit bank.

“TRU is leading a pilot project, started in December 2022, to explore the prospect of using a PLAR process to assess the micro-credentials that were funded in the first two rounds of government funding. Our group wants to investigate whether these micro-credentials could be considered for academic credit. This would allow learners to use their completed micro-credential as a springboard for further education. It aligns with the Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021)’s special consideration for laddering micro-credentials into other educational opportunities.

“The advisory committee for this project includes representatives from RRU, VCC, KPU, UBCO, BCCAT and TRU. As a first step, we assessed ten micro-credentials that were funded as part of the initial two rounds of funding by the Ministry of Post-secondary Education and Future Skills. We used the TRU credit bank evaluation tool, which we modified with some things we learned along the way from New Zealand, Australia, and the Open University in the U.K.

“There is interest in developing a provincial credit bank for micro-credentials. Such a credit bank would mean that PLAR credits are accepted across institutions. To develop this, it’s clear that there must be rigour and transparency in the evaluation process. The evaluation tools that we are using ensure this.

“Our group is also asking where and how micro-credentials could be housed in a provincial credit bank.

“There are some big questions in all this. Do we need a provincial credit bank? Would all post-secondary institutions accept a centralized credit bank? How would we develop and regulate a provincial credit bank? How do we resource it? There are so many questions to consider…

“Our pilot project is having vigorous discussions about how to create a framework for the micro-credential credit bank, and we are testing them at several institutions. Based on our experience, we will make recommendations to the province about how to move forward with both the future assessment of micro-credentials and the possible building of a provincial credit bank.”

Top Tips from TRU’s Experience with the Credit Bank

- Develop policies. Develop policies and transparent procedures to provide clarity and promote trust about the credit bank at your institution. Ensure that everyone is aware of them and that the policies are followed in a consistent manner.

- Promote the credit bank internally. Help faculty and administrators understand the value of a credit bank for recruitment, student retention and success, and funding.

- Promote the credit bank externally. Devote resources to ensure that adult learners and prospective learners are aware of this pathway for their educational journey.

- Resource the credit bank. Ensure there are adequate resources (staff and time) to carry out the credit bank process. This is very difficult for faculty and administrators to do off the side of their desks.

- Centralize the credit bank. The credit bank could be housed at one central location in the institution, or each academic department could host its own. TRU recommends a centralized location for the credit bank offerings to ensure consistency in practice and rigour, time savings by pooling resources, and to make the opportunities easier for students to find.

- Adopt a growth mindset. Credit banks are an emerging area of PLAR practice that aligns with the needs of adult learners in their career transitions. Dedicate resources to researching emerging practices and patterns in what and how adults are learning and be ready to pivot as these changes continue.

NAIT Innovates with Direct Assessment to Offer Micro-credentials

Patrick Weinmayr is former director of new product and Cindy Ough is the new products manager at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) in Edmonton, Alberta. At the behest of NAIT’s president Laura Jo Gunter, Weinmayr and Ough have been developing a new educational pathway for experienced learners called direct assessment (Note: Initially, this option was called a ‘direct credential’ but the name has been changed to reflect the activity rather than the attestation of learning). Below, they describe what they have developed and how it might help adult learners in their career journey.

Interview

What is direct assessment?

Weinmayr: “It’s a way for NAIT to certify that a person has certain competencies without requiring them to take a course.

“We started from a mindset that adults already have knowledge and competencies, which they picked up through work experiences, formal education, or that they taught themselves. They have these competencies, but they are not formally recognized by an accredited Canadian post-secondary institution. Sometimes a person needs that recognition. Perhaps they are applying for a job that wants evidence that they have these skills, or they want to apply for further education but first need to show they have a certain level of abilities.

“Normally, these people have one option. They sign up for a course or program that lines up with these competencies, complete it, and a few months later they receive the credential that certifies they have that competency. If you think about it, that’s not very efficient. They already had those competencies at the start. Direct assessment allows them to bypass the course.

“In practice, what happens is that they come to our website. We have developed a pre-assessment tool to help them decide whether they already have the competencies that align with a specific micro-credential. It’s a simple online survey with 15 to 30 questions (our pilot program for the Workers Compensation Board will be visible on our website sometime in the summer 2023). Once they complete it, they get a recommendation. Based on their answers, we tell them whether they should be taking the micro-credential program (the course-based pathway) or if they are a good candidate for the direct assessment pathway. The tool is just meant to help learners make a decision about which path to choose to earn the micro-credential.

“If they choose to go down the course-based path, then it’s what you would expect. They register for a program, take the courses, successfully complete the assessment, and they earn the micro-credential.

“If they choose the direct assessment route, they skip the course and take the assessment. If they successfully pass, then within a week or so, they earn the micro-credential. NAIT will have validated that they have those competencies.

“On their NAIT transcript and on their digital badge, the two options for earning the micro-credential — course-based or direct assessment — are indistinguishable. We have entered the two in our systems so that they are the same course, but what’s different is simply the delivery mode. To an employer looking at the credential, the two look identical.”

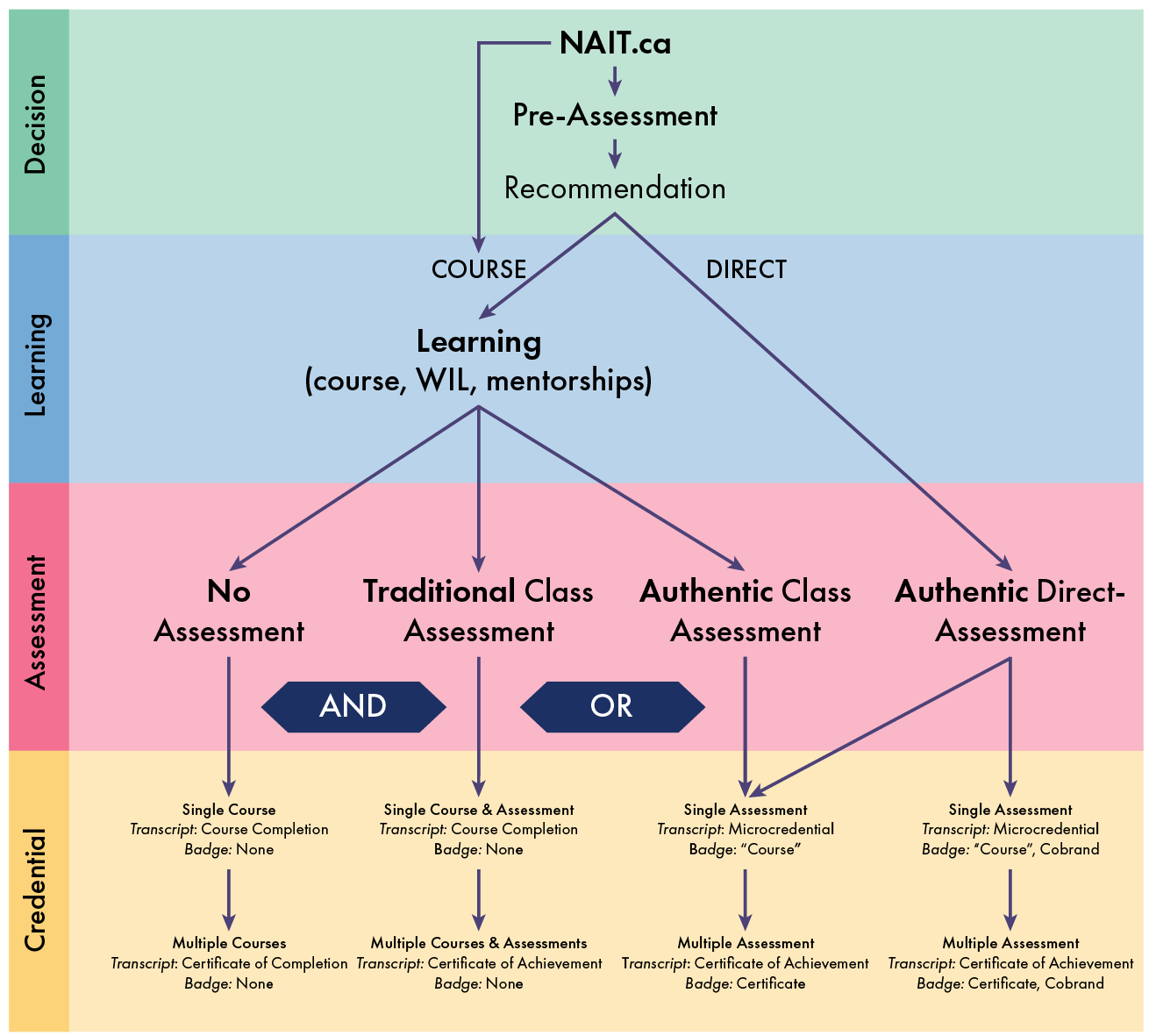

“We have found that this list of options and processes can be difficult for learners to navigate, so we have created a flowchart that shows the different pathways (Figure 7).”

Tell us about the assessment performed in a direct assessment.

Ough: “I should start by noting that the assessment method used for all of our micro-credentials — whether course-based or direct — are authentic assessments. They are not traditional assessments that assess theory and consist of a multiple-choice test with some short answer items. Rather, these are simulations. Learners are asked to demonstrate their skills through real-world scenarios.

“For example, let’s say the competency that you have to demonstrate is in using Excel to a certain level of proficiency. The authentic assessment is done online. Students get a screen that looks like Excel. They are not actually using Excel — we use a third-party software that mimics that environment and allows us to monitor the students’ activities on the software. Then we give them a scenario. It can be something like, here’s a spreadsheet with some data in it. Your manager asks you to clean up the data and show it in a graph with the following requirements. What do you do? The software monitors what the students do — how they get to the final product.

“In some cases, the demonstration of skills doesn’t involve a computer. For example, for a baking micro-credential, learners must demonstrate that they can use the right techniques to obtain a light and flaky crust. In this case, we have a software that learners can use to monitor themselves in their environment, performing the skill and filming it. The software allows them to record their performance from different perspectives, so they might set up a camera on their head, another pointing at the stove, and another at the inside of a mixing bowl. They can narrate as they perform the task, which can be helpful if they make a mistake during their demonstration, but catch it, and then problem solve around their mistake.

“We hire subject matter experts to review these assessments. They use rubrics, which we have developed, to assess the performance. This is important, because we want to standardize the assessment, so that all assessors will look for the same things. We are still debating whether we will assign grades or make it pass/fail, but right now we are leaning towards a pass/fail assessment outcome.”

Are the authentic assessments the same for the course-based and direct assessment micro-credentials?

Weinmayr: “No, they are not.

“The assessments we use for the course-based and the direct assessment evaluate the same competencies, so they are similar. However, one thing we found is that in a course, an instructor gets to know each learner and so by the time the student engages in the assessment, the instructor has more than the performance that’s being demonstrated right in front of them to assess whether the student can perform the task well.

“For a direct assessment, assessors do not have this data to draw from. The assessment must do a little more to convince us that the student can do the skill. It’s not that the assessments are harder, but we are going to make doubly sure that the person can do those skills. For us, this is a way to manage our reputational risks.