Design Considerations: Practical Guide

Chapter Audience:

Program Managers

Program Managers Faculty

Faculty

Design Cycle

Creating a new micro-credential program involves the input of several stakeholders, such as employers, subject matter experts, learners, media designers, instructional designers, ICT support staff, and possibly other institutions. This introduces more complexity than in the development of traditional post-secondary programs and it must be managed. While there are many instructional design models that a team can use to guide the creation of a new program, ADDIE and SAM are the most common.

ADDIE

The most commonly used instructional design model is ADDIE, composed of the following steps:

- Analysis.

This step involves conducting a needs assessment and environmental scan, as well as identifying the resources needed to implement the program. How to conduct a needs assessment was described in the chapter Financial Matters. Consider also consulting van Vulpen (2020). - Design.

This is where the blueprint of the program is sketched out. This means identifying the program’s learning outcomes, assessments, structure, format, and activities. In short, this is where the syllabus is created. For micro-credentials, this planning is often done as a team effort in order to incorporate the expertise and perspectives of employers, subject matter experts, and instructional designers. - Development.

At this stage, the learning materials are created. This means producing the videos, readings, lesson plans, activities, assignments, assessments, and online course contents. This is typically assigned to a subject matter expert, who works in conjunction with an instructional designer and a media specialist. Employers can provide input in the form of sample problems and case studies from the workplace or feedback on the content’s relevance. - Implementation.

This is where the course is launched and offered. Instructors use the lesson plans to deliver the content, while learners participate in the course and engage with the materials. - Evaluation.

Although placed last, data collection for the evaluation of a program happens at every step. However, after running through one round of the pilot offering, it may be worth assembling the whole team to review the data and plan for improvements for the next offering of the program.

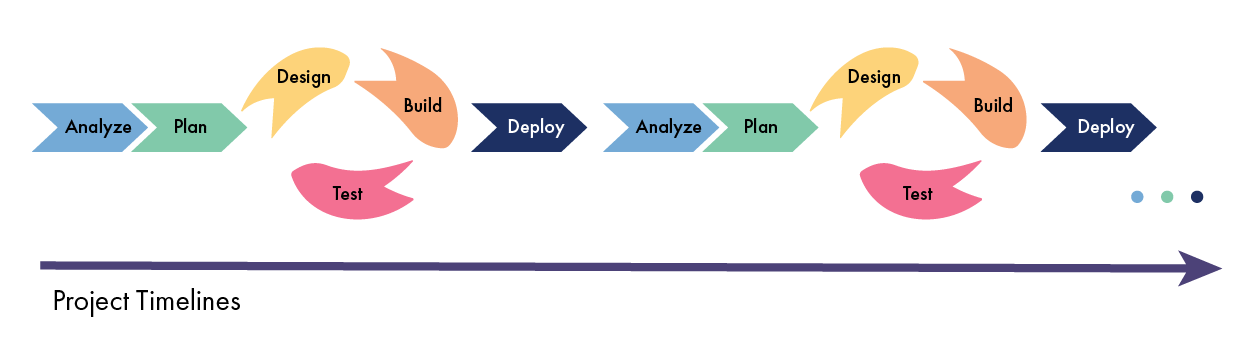

Figure 1 shows the ADDIE instructional design process. For more information on this approach, including its benefits and limitations, see Chapter 4.3 The ADDIE Model in Tony Bates’s book Teaching in a Digital Age (2022).

SAM

Another popular approach is the successive approximation model (SAM). Figure 2 is a diagram showing the stages of this process. SAM applies principles of agile project management to instructional design. As such, it is a cyclical model that is based on the idea that instructional design is an ongoing process of successive refinement. Rather than creating a whole course and launching it (as prescribed by ADDIE), this approach builds the micro-credential in stages and pilots each one in turn. In other words, the ADDIE steps of Design, Development, and Evaluation are applied to smaller, usable chunks of the complete program such as one module or the online course structure. By giving learners an opportunity to provide feedback at these early stages, and acting on that feedback, the final product is more likely to meet their needs than when using the ADDIE approach. Adopting this instructional design model requires having a pool of learners to test the nascent program at each round of iteration.

Other Instructional Design Models

Although these are the most popular instructional design models, there are several others to pick from. The InstructionalDesign.org website (Kearsley & Culatta, 2023) provides a list of dozens of other models along with a description of each one.

Team Design Process

Team Member Roles

The involvement of many stakeholders in the creation of a micro-credential may require the articulation of clear roles and responsibilities for each contributor. While each team will have its unique set of contributors, common roles include:

- Instructional designer. This person often serves two roles. As project manager, they facilitate the contribution of each team member and lead the project toward completion. They also apply their instructional design expertise to guide the creation of an educationally effective learning experience. They facilitate conversations to identify learning outcomes, choose the most appropriate course structure, guide the creation of its content, and ensure effective use of the learning management system.

- Subject matter experts (SME). These people have expert knowledge of the topic. They may be faculty and may also be working professionals. Often, the input of more than one subject matter expert is included in the creation of a micro-credential. Subject matter experts can help in designing the program, developing its content, and even delivering it as instructors.

- External stakeholders. Micro-credentials serve the needs of external stakeholders, such as employers, community partners, and Indigenous communities. As such, their input should be solicited and included at several stages of the program’s creation. For example, employers may inform the needs assessment, could provide materials such as case studies and authentic assignments taken from the workplace, and can validate the curriculum to ensure that it is relevant and meets their needs.

- Media specialist. Courses developed for an adult audience often require a higher level of production than those intended for traditional post-secondary learners. Such courses may include original images and videos that show workplace settings. A media specialist who can design graphics, take photographs, and produce short videos tailored to the course can help elevate the course’s overall quality and enhance its appeal to adult learners.

- Learners. The input of learners should be sought throughout the development of the program to ensure that what is developed meets their needs and expectations.

In the companion chapter Design Considerations: Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector, one instructional designer describes her role in coordinating the input of over 20 stakeholders to create a coherent and instructionally effective micro-credential (see the section An Instructional Designer’s Role in Creating FILMBA (CapU’s Experience) ).

Facilitation Tools

Many approaches can be used to solicit the input of each stakeholder and incorporate it into the design of the curriculum. Some to consider include:

- ABC Learning Design is a collaborative, workshop approach to rapidly designing a new course. Originally developed at University College London, ABC has been adopted by several organizations (including the Chang school of continuing education at Toronto Metropolitan University) to help multiple subject matter experts come together to create a course. All of the materials to conduct each stage of the workshop are available on the ABC website for re-use under a CC BY NC SA 4.0 license (Young & Perović, 2015).

- Developing a Curriculum (DACUM) is an approach commonly used to design competency-based programs such as vocational and trades training. It is implemented during the initial stages of program design and involves people who work in an occupation, rather than leaders or educators, to identify the essential tasks associated with the profession. It is described in more detail in the Developing a Curriculum (DACUM) section below.

- Rapid Development Studio (Mei et al., 2021) is a collaborative approach to designing online courses over a rapid, two-week period.

- Collaborative Mapping Model (Drysdale, 2019) was developed by an instructional designer to help faculty understand the role of each member of a team in a collaborative curriculum design project.

- Design Thinking is an approach to designing a product or service that meets the needs of end users. Though not specifically created for instructional design, its principles can be applied to this process. The approach involves five steps (Friis Dam, 2023):

- Empathize, where the designer tries to understand the end-user’s needs and preferences;

- Define, where the designer identifies and articulates the goals of the project;

- Ideate, which is the brainstorming stage during which various ideas are generated;

- Prototype, where a few of the most promising ideas are transformed into models and tested; and,

- Test, where the most viable model is chosen and tested with end-users.

A series of tools facilitate each step (IDEO.org, 2015).

- Liberating Structures (Lipmanowicz & McCandless, 2015) is an approach to facilitating group conversations that ensures everyone is given a voice. While the set of 35 tools was not created to facilitate curriculum development, the tools can be used for that purpose. For example, the tool “25-10” could be an effective way to help a group of stakeholders prioritize and reach consensus about a program’s learning outcomes. The tools are licensed under CC BY NC.

The Suggested Resources section provides links to additional resources for instructional design including tools to develop content.

Adult Learners and Andragogy

Characteristics

Micro-credentials typically target adult learners. As popularized by Malcolm Knowles in the 1980s, adult learners come to the learning experience with distinct characteristics that differentiate them from traditional learners entering post-secondary from high school (Pappas, 2013a). Adult learners often have work experience, are more purposeful in their training goals, want to connect what they are learning to their lives, and have competing demands on their time (e.g., family and/or work in addition to education). Here are some of the common expectations that adult learners bring to their learning (Anders, 2023; ELM Learning, 2022a; Hepburn, 2023; Mahon, 2021; Pappas, 2013b; Rosario, 2023):

- Flexibility.

Adult learners often have busy lives with work and family responsibilities. They want their education to be flexible, allowing them to study at their own pace and on their own schedule. - Relevance.

Adult learners have a utilitarian mindset and are pragmatic in their learning goals. They want to acquire knowledge and skills that are immediately applicable to their lives and careers. They generally do not value theory and prefer practical knowledge. They seek to boost their confidence and reach their career goals through tangible skills development. - Self-directed.

Adult learners take responsibility for their own learning. They want to have a say in what they learn, how they apply it, and how they can demonstrate their abilities. They also appreciate self-assessment to gauge their learning. Finally, they view their instructor as a peer. - Recognition of prior learning.

Adults are not empty vessels; they come to education with a wealth of experiences and knowledge that they want validated and valued. They want to interact with other learners, instructors, and professionals in their field to network, collaborate, and learn from each other’s experiences. - High expectations.

Adult learners are returning to education by choice. They have often been exposed to high-quality professional development materials in their workplace and through private providers. For these reasons, they adopt a client mentality. They expect customized service and high-quality experiences that generate immediate results.

Distinction Between Andragogy and Pedagogy

The teaching of adult learners and its practices is called andragogy. The teaching of younger learners and its practices is called pedagogy. Table 1 captures some of the ways in which andragogy and pedagogy impact the design of instruction (ELM Learning, 2022b; Nebel, 2022; UIS, 2022; WGU, 2022).

| Andragogy | Pedagogy | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Approaches to teaching adult learners. | Approaches to teaching younger learners. |

| Goal Orientation | Applying knowledge to real-world situations. Utilitarian focus. | Knowledge acquisition. Focused on learning facts and includes a lot of theories. |

| Motivation | Intrinsic motivation drives learning, such as self-determination and personal goals. | Extrinsic motivations to encourage learning, such as grades. |

| Learner’s Prior Experience | Valued. Recognizes that learners have existing knowledge and professional experience to bear on the topic. | Ignored. Learners are assumed to be “empty vessels,” with no prior knowledge or experience of the topic. |

| Role of Instructor | Facilitator. | Lecturer. |

| Learner Orientation | Learner-centred with the learner taking responsibility for their learning. | Instructor-centred, with the instructor directing the process. |

| Learning Resources | Learners exercise choice in selecting resources. | Instructor selects a set of common resources for all learners. |

| Curriculum | Flexible. | Rigid. |

| Leaning Pace | Self-paces. | Instructor-led. |

| Assessments | Renewable assignments (i.e., assignments that have a real-world utility, such as a formulating a budget that learners can use in their job). | Disposable assignments (i.e., assignments completed only for purpose of assessing skills and abilities). |

Recommended Approaches

In some contexts, pedagogy will be the best approach for adult learners. Consider, for example, programs for adults who are changing careers and have no prior experience with the new topic, or for programs where there is a need to assess learners in a standardized, industry-specified manner (e.g., to prepare for industry licensing exams). In such instances, pedagogy (or a blend of pedagogy and andragogy) might be the best approach.

In instances where learners expect to be self-directed and have prior knowledge or experience with the topic, an andragogical approach is the better choice. Program designers will need to consider ways to address the learners’ needs and expectations, as described in the Characteristics section above. Here are some recommendations for addressing them:

- Treat them like adults.

Many of the recommendations boil down to this. Treating someone as an adult means valuing what they contribute to the learning environment in terms of their knowledge and expertise, trusting their autonomy and allowing them to reach their individual goals by giving them choice, and respecting their time. It also means that the instructor should treat them as peers, not pupils. - Provide flexible formats.

To accommodate the busy schedules and commitments of adult learners, offer flexible learning options, such as online or hybrid courses or programs offered on the weekend. - Prioritize relevance.

As explained by Becker (2022), as self-driven learners, adults need to understand the “why” of each learning activity. Becker suggests writing explicit rationales for each assignment or activity. Adult learners also need to see the connection between the content they are learning and their lives and work. The course design should use real-world examples, case studies, and project-based learning opportunities and ask learners to apply what they learn to their work context. - Allow choice.

Each adult learner has different goals in taking a training program. Help them meet those goals by providing them with flexibility in selecting their resources, assignments, and assessments. This could include offering an assortment of readings and videos, allowing learners to select those that are most relevant to their goals, and providing opportunities for learners to apply their learning to their own work contexts, such as creating a communication plan for their workplace. This practice aligns with the Universal Design for Learning’s recommendations to provide multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2018). - Foster collaboration.

Adult learners benefit from collaborating with peers. It gives them a chance to share what they know, build on past learning, and analyze it in a new light. Course design should provide opportunities for learners to work together and learn from each other. Crockford (2021) suggests a few formats to facilitate this, such as discussion forums, social media tasks, and a “question of the week” exercise. The instructor’s task is to foster a safe and respectful learning environment where adult learners feel safe to share their ideas, experience, and perspectives. - Include reflective activities.

Kolb (1984), drawing on Dewey (1938), emphasized the importance of experience and reflection in learning. According to these education research pioneers, people continually develop hypotheses about the way that the world works, use observations to test them out, and then reflect to reassess their models. For this reason, adult learners need periods of reflection to articulate how new learning and experiences align, as they build revised models of how things work. - Provide timely feedback.

Adult learners need ways to gauge whether they are meeting their goals and identify what needs to be corrected. The instructional design should include ways for learners to self-evaluate, to integrate peer feedback, and for instructors to provide timely and constructive feedback on learners’ progress and performance. - Respect different learning speeds.

Adult learners may proceed at different learning speeds due to their prior knowledge or, more pragmatically, because of the amount of time they can devote to learning due to other commitments. Instructors should be flexible in pacing and provide additional support when needed.

The Suggested Resources section suggests articles that share best practices for designing programs for adult learners.

Competency-Based Education

The Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021) offers the following definition for micro-credentials in this province.

According to this definition, one of the features of micro-credential training is that it is competency-based. This section describes what that is and how to design it.

What is a Competency?

In familiar language, competence is the ability to do something successfully and efficiently. Competency, in the context of education, is more specific, and this definition will be explored in this section.

Lena Patterson, program director of micro-credentials and business development at the Chang school of continuing education at Toronto Metropolitan University, and a thought leader in micro-credentials, offers the following definition of competencies (see the Suggested Resources for more on Patterson’s definition of competencies). Competencies are…

- Composed of three elements:

- Knowledge, which is the foundation upon which a learner can act;

- Skill, which is the application of that knowledge;

- Attributes, which are the values that are essential to the performance;

- Performed in specific contexts;

- Dynamic and associated with frequent renewal.

To illustrate the three elements of a competency, Patterson uses the example of learning to drive a car. When a person learns to drive a car, they must first pass a knowledge exam, showing that they know the rules of the road (e.g., how to enter and exit a modern roundabout). Then they practice on the road under the supervision of a family member or friend. This is where they apply their knowledge and rehearse the skills. They learn to parallel park, translating the knowledge of how to do it into a skill. This includes adopting some attitudinal behaviours, such as being respectful of others who share the road. Once they feel they are competent, learners take a road test, which a professional assesses. During this practical test, the learner must show their ability to perform each skill to certain standards.

Once they pass this exam, they are deemed competent to operate a vehicle. Note that this competency is context dependent. If a person moves from B.C. to the U.K., their competencies may no longer be relevant to driving a car and the person may need to acquire new knowledge and develop new skills, such as driving on the left-hand side of the road. Moreover, a competency is only indicative of an individual’s abilities at a particular moment in time. They may need to be reassessed, and there may be an expiry date that necessitates periodic re-evaluation of a person’s competencies.

Another thought leader in this field, Dennis Green, co-wrote the eCampusOntario Open Competency Toolkit. He defines competency as the specific and measurable combination of knowledge, skills, and attributes that result in the performance of an activity or task to a defined level of expectation or performance standards (see the Suggested Resources for more on Green’s conceptualization of competencies). These performance standards can be used to design assessments.

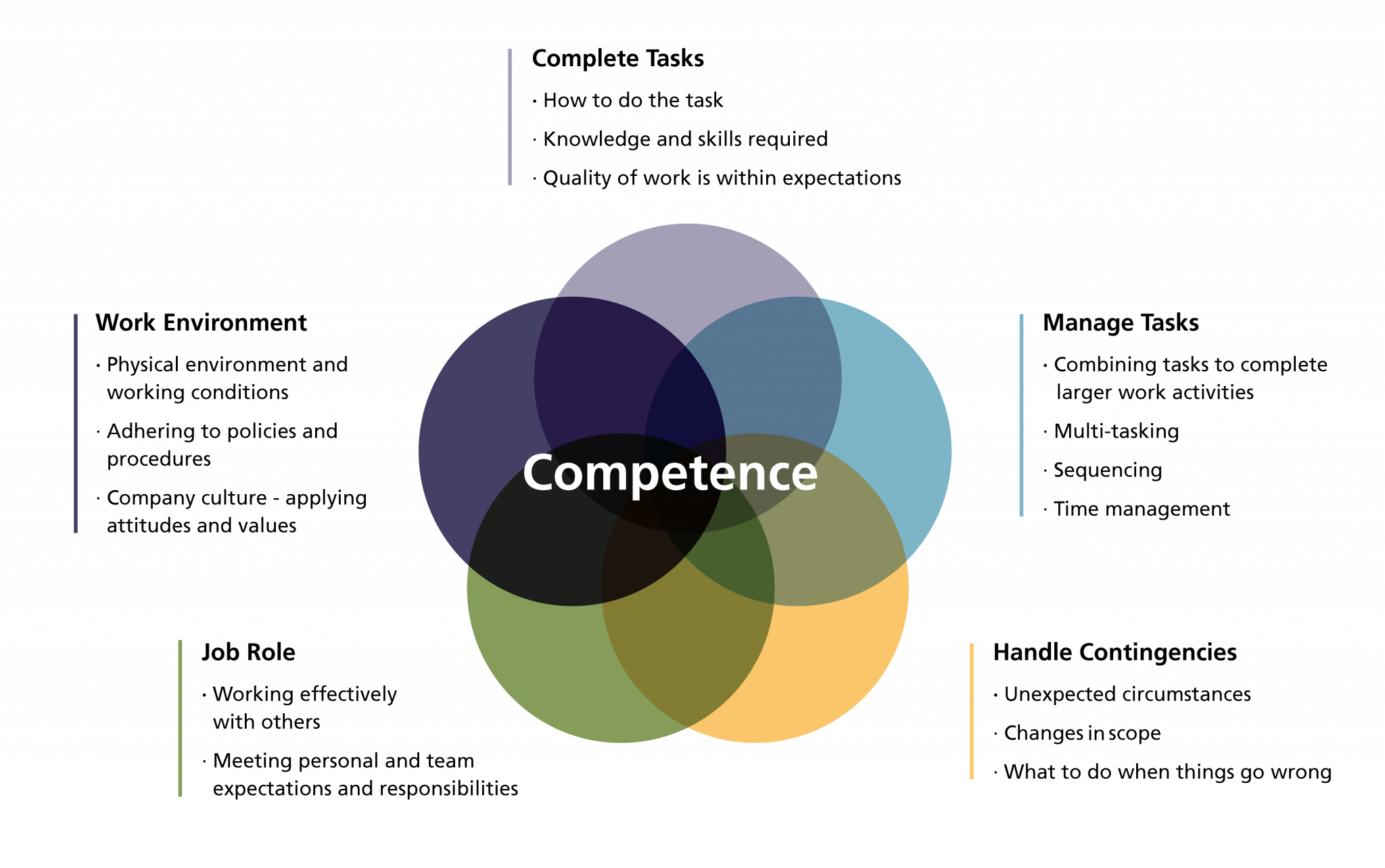

Green emphasizes that being competent also means having the ability to handle unexpected circumstances and select an alternative path forward when things go wrong (see Figure 3).

Green also emphasizes the distinction between activities and competencies. One way to think about the distinction is to consider a job posting or job description. What is typically listed under the heading “responsibilities” constitutes the list of activities that a person in this role will be required to do. What’s listed under “qualifications” usually consists of a mix of competencies and required education.

For example, in preparing a meal, a cook will be required to engage in the following activities: find a recipe, gather the ingredients, prepare the dish, set the table, serve the food, clear the table, and clean up the kitchen.

Each of these activities depends on a set of about five competencies that are necessary to carry out any cooking activity (whether barbecuing meat or baking a cake). These food preparation competencies include using recipes to prepare food, handling kitchen tools and equipment, applying various cooking and baking methods, adhering to safe work practices, and following safe food handling procedures.

The construction of a competency statement is similar to that of a learning outcome. It is composed of three elements:

- Action: What the person is expected to do. The statement always begins with a concrete action-oriented verb (e.g., manage, handle, clean);

- Context: The situation or environment in which the action is to be demonstrated;

- Criteria: The standards or requirements that the action must meet to be deemed satisfactory.

Green provides the following example of a competency statement:

This is usually accompanied by a performance criterion. In the above example, the performance criterion would define what “handling” means — in this example, “selecting, using, and storing appropriately.”

Many competencies are similar across occupations and what varies is the context in which they are applied.

Readers are directed to the companion chapter Educational Pathways for ideas on how to integrate competencies into a degree program (see the section Role of Competency-Based Education in Undergraduate Courses).

Competency Frameworks

Competencies don’t stand alone. They are often interrelated to one another and grouped together, particularly in the context of an occupation. An organized collection of competencies required to complete an activity is called a competency framework.

A competency framework can be used to identify and assess the skills of employees, improve the hiring and promotion process, provide guidance for the development of training, and evaluate the effectiveness of that training.

Many organizations develop competency frameworks. Places to look for existing occupation competency frameworks include:

- Professional associations or regulators;

- Industry;

- Governments (especially in the European Union, but the Government of Canada is beginning to develop such frameworks);

- Large organizations, such as UNESCO.

Here are some examples of competency frameworks for diverse occupations:

- K-12 teachers (Government of Quebec, 2021);

- Staff working at the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA, 2016);

- Career development professional (Canadian Career Development Foundation, 2021);

- Climate adaptation specialization (Adaptation Learning Network, 2021);

- Educator, ICT specialization (UNESCO, 2018);

- Educator, OER specialization (UNESCO, 2016);

- Health informatics professional (Canada’s Health Informatics Association, 2012);

- Instructional designer (University of South Florida, 2023);

- Nurse practitioner (Canadian Nurses Association, 2010);

- Plumber (Ontario College of Trades, n.d.);

- Public servant, data competency specialization (Government of Canada, 2023);

- Registrar (Archives and Records Association, n.d.);

- University administrator (Niewiesk & Garrity-Rokous, 2021).

If there are no existing, or accessible, competency frameworks for the occupation of interest, then it might be necessary to create one. To create a competency framework, you must first identify the core competencies that are necessary for each job in the organization, such as problem-solving, communication, teamwork, and leadership. Once the core competencies have been identified, you can create a set of specific, measurable activities that demonstrate each competency. Although there are no set rules, most competency frameworks contain between 10 to 50 competencies. See the Suggested Resources section below for support.

There is a movement to create open competency frameworks. The Open Skills Network is one such effort that brings together industry leaders with representatives from the education sector. The goal is to create an open skills library that is publicly available. This movement comes out of a recognition that many organizations are duplicating their efforts. For example, if one company creates a competency framework for a software analyst role, it is likely to be very similar to the competency framework created by another organization for the same job. An open competency framework would provide a common language and set of standards for assessing and developing competencies that can be applied across different contexts and organizations.

In addition, there is a desire to develop a standardized model for storing competency data digitally. This will facilitate interoperability between computer systems involved in the labour market (for example, LinkedIn) and an organization’s job posting, so that the system can automatically recognize competencies in an applicant and match them to a job. To achieve this goal, there needs to be standards for the way in which competencies and competency frameworks are described, and how the information is organized and stored. This will make them machine-readable and allow the transfer of information between post-secondary institutions and employers. Eventually, open competency frameworks will provide the infrastructure to connect and link micro-credential holders with employers.

What is Competency-Based Education?

In his book Teaching in a Digital Age (2022), Tony Bates provides the following description of competency-based education:

Competency-based learning begins by identifying specific competencies or skills, and enables learners to develop mastery of each competency or skill at their own pace, usually working with a mentor. [..] The value of competency-based learning for developing practical or vocational skills or competencies is more obvious, but increasingly competency-based learning is being used for education requiring more abstract or academic skills development, sometimes combined with other cohort-based courses or programs.

Competency-based education is an approach to learning that emphasizes the acquisition of skills or abilities (i.e., competencies) rather than simply the amount of time spent in a course or the memorization of a list of concepts. It considers that learning has been achieved when the learner can demonstrate the application of their knowledge in specific contexts and to certain standards. As such, it tends to use instrumental learning, in which feedback is used to strengthen or weaken behaviours, thereby leading to improved performance.

The focus on demonstrated skill rather than on time spent learning is a shift to learner-centered learning. In contrast, the traditional post-secondary system tends to focus on defining course scope in terms of the amount of time spent learning, which primarily serves the needs of program administrators (e.g., for resource allocation such as instructor compensation and classroom scheduling). However, this approach does not necessarily serve the needs of adult learners who often come to a course with different backgrounds (which may have exposed them to some of the course contents) and who learn at different pace. Therefore, assigning a fixed number of hours, such as 40 hours, to a program is not a learner-centered way of describing a micro-credential.

Table 2 provides a comparison of key features between competency-based education and the traditional approach used in post-secondary education.

| Competency-Based Education | Traditional Education | |

|---|---|---|

| Goals | Emphasizes mastery of specific competencies that are relevant to real-world contexts. | Emphasizes the acquisition of knowledge and a focus on the learning process. |

| Assessments | Frequent, ongoing assessments to provide feedback to learners as a means of improving their performance. Often uses authentic assessments where learners demonstrate that they can apply their knowledge in real-world situations. Uses criterion-referenced assessments, which have a predetermined standard or goal. |

Focused on the completion of coursework and uses summative assessment at the end of a unit. Learners take tests and exams to demonstrate they have comprehended the materials. Frequent use of norm-referenced assessment (e.g., bell curve grading where learners are assessed against one another). |

| Time and Pace | Schedule allows learners to proceed at their own pace and complete assignments and assessments when they are ready. | Fixed schedule where learners progress through a curriculum at a common predetermined pace. |

| Curriculum | More individualized curriculum depending on learner’s existing knowledge and skills (i.e., learner may “test out” of certain modules if they can demonstrate existing competencies). Usually streamlined and focused on specific skills and competencies. |

Set curriculum for all learners. Often covers a range of topics and subject areas. |

| Instructional Methods | Include individualized instruction (tutor supports a learner through the course), project-based learning, and other approaches that encourage learners to apply their knowledge in real-world situations. | Often focused on content delivery that takes the form of lectures and other instructor-centered approaches. |

| Admission Requirements | Generally, less stringent, with learners being assessed on their skills and knowledge. | Generally, more stringent, with learners being assessed on their academic records. |

Why Adopt Competency-Based Education?

As asserted by Bates (2022), competency-based education is not new. It has been a hallmark of the trades, continuing education, and health professional education for decades. Western Governors University in the United States offers degrees based entirely on this model.

The recent and broader interest in competency-based education comes from many sources, notably in the recognition of the “60-year curriculum” (Richards & Dede, 2020), which is the idea that people are now in the workforce for 60 or more years and that the training they received at the beginning of their career will not sustain them throughout their entire work life. People need to be retrained, upskilled, and retooled, whether they stay in the same occupation or change jobs.

This close connection between education and work requires some “translation” between the two cultures. In post-secondary education, achievements are captured in a transcript, which lists the courses that the learner took and the grades they obtained. This doesn’t translate well outside of academia. To a hiring manager, a grade of “A” in the course 20th Century Literature doesn’t explain what the learner can do. That’s where competencies can serve as a common language between the two worlds. Articulating that in the course the learner demonstrated the ability to find evidence, persuade others, exercise critical thinking through analysis, and write cogently can serve the needs of both academic institutions and employers.

Most competency-based programs identify the competencies for a program in partnership with employers. This ensures that the competencies in a program match those needed by the workforce. Competency-based education is the preferred approach for micro-credentials because it allows learners to demonstrate mastery of concepts and skills to employers, an important element when using the training to upskill or retool in their careers.

Bates (2022) notes that competency-based education is particularly suited to adult learners because the format allows learners to customize their education. It establishes a set of competencies that the learner must demonstrate to earn recognition for successfully completing the program. A learner who comes in with prior experience with a particular competency can opt to proceed directly to the assessment stage, saving themselves the time that a traditional program would force them to take to (re)learn the material. Learners can then allocate their time to learning new skills. It’s a form of individualized learning. It also motivates learners by asking them to self-monitor their learning, resulting in a greater sense of ownership and investment in the learning experience.

Competency-based education has been found in several studies to be effective at improving student learning outcomes (Chen et al., 2022; Rivers & Sebesta, 2017).

Developing a Curriculum (DACUM)

Earlier in this chapter, several approaches to weaving the input of several experts in the development of curriculum were presented. One approach is often used when creating competency-based curriculum, particularly if it is aligned with a specific occupation. This approach is called developing a curriculum (DACUM). It is a job analysis process created at the University of British Columbia and it is now used around the world (Joyner, 1996). During the DACUM process, a group of subject matter experts (SMEs) work together for a couple of days to identify the competencies required for successful performance in a particular occupation. DACUM is often used in vocational and workforce development programs to ensure that the training created is relevant to the needs of employers and industry.

The DACUM process typically involves the following steps:

- Define the occupation to be analyzed.

This involves identifying the job title, job description, and any other relevant information about the occupation. - Select a panel of subject matter experts (SMEs).

The panel should consist of five to 12 individuals who are knowledgeable and experienced in the occupation. - Brainstorm the competencies.

The SMEs participate in a brainstorming session to identify the key competencies required for successful performance in the job. The facilitator uses a variety of techniques to solicit ideas and encourage discussion. - Cluster competencies and tasks.

The competencies identified in the brainstorming session are grouped into functional areas or clusters. This organizes the information and can help to identify any gaps and redundancies in the analysis. Typically, the competencies are organized into a DACUM chart (i.e., a storyboard for the course) that shows how the competencies build upon one another to be successful in the chosen occupation. The DACUM chart can serve as a basis to conduct a needs assessment, develop curriculum, or evaluate worker performance. - Validate the analysis.

The analysis should be reviewed by additional SMEs or industry representatives. This step is important to ensure that the competencies and skills identified in the analysis are relevant and accurate. - Develop a competency-based curriculum.

Based on the results of the analysis, a competency-based curriculum can be developed. This curriculum should identify the specific competencies and skills that trainees should master in order to successfully perform the job. - Implement and evaluate the curriculum.

The curriculum should be implemented and evaluated to determine its effectiveness in preparing learners for work.

The Suggested Resources section contains links to handbooks with instructions for implementing the DACUM process as well as examples of DACUM charts.

There are several reasons why the DACUM process is used to design job-specific and competency-based curriculum. Here are key benefits:

- Efficient, time-saving process.

DACUM is conducted over a couple of days rather than the weeks it can take to conduct a similar analysis using other approaches. - Alignment with industry needs.

The process involves the participation of industry representatives and subject matter experts, which helps to ensure that the resulting curriculum is relevant and aligned with industry needs. It also maximizes buy-in from workers and employers. - Focus on competencies and skills.

By identifying the specific competencies and skills required for successful performance in a job or occupation, the DACUM process helps to ensure that the resulting curriculum is targeted and effective. - Customization to specific jobs and occupations.

The process can be tailored to specific jobs and occupations, which helps to ensure that the resulting curriculum is job-specific and meets the unique needs of the occupation. - Consensus building.

Unlike other methods of collecting this data such as surveys, the process requires that subject matter expert discuss the competencies and reach consensus. This compensates for the biases that might be introduced by collecting individual inputs and builds a stronger product. - Use of a structured process.

The process provides a structured approach to curriculum development, which helps to ensure that all relevant competencies are identified and addressed in the curriculum.

While the DACUM approach is an effective method for developing job-specific and competency-based curriculum in many contexts, here are situations where it may not be appropriate:

- Lack of facilitation skills.

The approach requires that a person trained in its approach and skilled at facilitating a group leads the process. - Lack of subject matter expertise.

The process relies heavily on the participation of subject matter experts, so if there is a lack of expertise in the area being developed, the resulting curriculum may not be effective. Similarly, if there is limited employer involvement, the resulting curriculum may not be relevant or responsive to industry needs. - Lack of flexibility.

The process can be inflexible, with a strong focus on identifying specific competencies and skills required for a job or occupation. If there is a need for more flexibility or adaptability in the curriculum, this approach may not be the best fit. - Inappropriate for academic disciplines.

The DACUM approach is typically used in vocational or technical education settings, where there is a focus on job-specific skills and competencies. It may not be appropriate for academic disciplines, where the focus is on broader theoretical knowledge and critical thinking skills.

Assessment of Learners

The assessment of learners is an essential component of a micro-credential (Oliver, 2021). In the Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021), assessment is included in the definition of a micro-credential and this aspect is expanded upon in the framework:

Assessment

Assessment of a student’s learning is required to ensure learners have achieved the intended competency. Assessment should be relevant to how employers recognize a competency has been obtained.

Micro-credential Framework for B.C. Public Post-secondary Education System (2021)

Assessments should align with the stated learning objectives or competencies of the micro-credential and measure whether the learner has successfully mastered a specific skill. Assessment is essential to establish confidence that the micro-credential has achieved its purpose (Chaktsiris et al., 2021).

Resources on designing assessments are included in the Suggested Resources section under the heading Learner assessment resources. Note that Angelo and Cross (1993) (for in-person courses) and Conrad and Openo (2018) (for online courses) come highly recommended.

One of the ways in which micro-credentials differ from many non-credit continuing education programs is in their formal assessment of learners against established standards. In the companion chapter Design Considerations: Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector, the story of RRU’s Transformation of Existing Courses into Micro-credentials illustrates how institutions may be able to create new micro-credentials by modifying existing continuing education programs instead of developing them from scratch.

Validation by Employers

An important factor in designing assessments for micro-credentials is to ensure that they are employer-informed (Bigelow et al., 2022). The assessment should be accepted and trusted by employers as an indicator that a learner has met the competency requirements and is able to use the acquired skills in a work setting. This links naturally to the next section…

Authentic Assessment

Authentic assessments are an emerging high-impact practice for micro-credentials (Gooch et al., 2022). Authentic assessments ask learners to demonstrate their understanding of concepts in a real-world context (Wiggins, 2006). They are designed to simulate the tasks or problems that learners might encounter in their careers or in their everyday lives. The goal of authentic assessment is to provide a more accurate and comprehensive picture of what learners know and can do.

Authentic assessments differ from traditional assessments such as multiple-choice tests in that they typically involve open-ended questions or tasks. They present complex, context-rich scenarios that don’t have a “right answer” and ask learners to make decisions and compromises as they propose a solution. Thus, authentic assessments, while they can be formative or summative, also help learners to develop important skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, communication, and collaboration.

Some authentic assessments are “renewable assignments” that have a real-world utility, compared to their more traditional “disposable” counterparts, where learners complete a task, submit it for a grade, and that’s the end goal (Veletsianos, 2017). Such renewable assignments are more motivating for learners to complete.

Authentic assessments may take many forms, including:

- Creating a video of the learner performing a task and asking them to explain some of the key considerations for effectively executing the task as they perform it;

- Analyzing a real-world case study and developing recommendations for a solution;

- Creating a business plan for the learner’s company;

- Conducting a scientific experiment and presenting the results at a conference;

- Creating artwork, to be included in a portfolio;

- Conducting a needs assessment for a community or organization and presenting the findings;

- Performing a musical piece in front of an audience;

- Developing a website or mobile app that addresses a real-world problem;

- Conducting a field study of the climate change adaptation preparedness of a town and presenting the findings at a council meeting;

- Designing and implementing a community service project;

- Designing and implementing a social media marketing campaign for a real organization;

- Producing a video documentary on a social issue or historical event;

- Designing and building a prototype of a new product;

- Conducting an audit of an organization’s financial statements and presenting the findings;

- Creating an infographic or data visualization to communicate complex information;

- Developing and delivering a professional development workshop or training session on a relevant topic;

- Writing a grant proposal for a community project or initiative.

Rubrics

Rubrics are often used in authentic assessment (Conrad & Openo, 2018; Reddy & Andrade, 2010). A rubric helps learners to better understand what is expected of them and what criteria they must meet to be successful. However, it is important to note that rubrics are not always required for assessments, especially if the instructions and criteria of the assessment are clearly explained and learners know what they need to do to reach a specific benchmark (e.g., a grade of 80% or higher). Rubrics do, however, provide learners with instructions and guidance on how to complete an assessment effectively.

Micro-credential Assessment Framework

The eCampusOntario’s Micro-credential Framework provides the following guide to help instructional designers develop appropriate assessment methods. The guide is reproduced in Table 3.

| PURPOSE

When developing an assessment for a micro-credential, start with two simple but complex questions: |

|

|---|---|

| RELEVANCE

Once the purpose of the micro-credential has been set, next comes the work to identify the specific contexts where learners will be expected to “do” the skill targeted by the micro-credential: |

|

| CHOICE

Offer flexibility through assessment design. Learners can demonstrate competency or mastery in a variety of ways (Acree, 2016). After collaborating to identify how learners can demonstrate their mastery of a competency, consider how they might choose to share their learning in a variety of formats (or multiple means of representation and engagement) (UDL On Campus, n.d.): |

|

| CONNECTION

Connection between learners and instructors is a high-impact teaching practice known to increase learning (University of Waterloo, n.d.). Building connection between micro-credential partners through assessment offers a powerful opportunity for a micro-credential to meet its outlined purpose: to fit a clearly identified need for a competency. To facilitate connection through assessment, consider: |

|

| FEEDBACK

Providing meaningful feedback to learners throughout the micro-credential invites reflection on the core competency targeted by the micro-credential offering. The purpose of any assessment is feedback (Wiggins, 2006). To provide meaningful formative assessment and feedback within a micro-credential offering, consider: |

|

| ITERATIVE DESIGN

To incorporate perspectives of all members of the micro-credential ecosystem, adopting a flexible and iterative design approach provides opportunities to evaluate and revise offerings in a cycle of evaluation, analysis, and revision (Mei et al., 2021). Adopting an iterative design and evidence-based approach to micro-credential projects might look like: |

|

Delivery Format

In-person, Online, and Hybrid Delivery

Some of the considerations for the delivery format (i.e., whether the training will be offered in-person, online, or in a hybrid mode) have already been addressed in the section on Adult Learners and Andragogy. The key is to consider the format that is best suited to achieve the learning outcomes or competencies, as well as address the needs of adult learners. Some administrative and design considerations are also listed in Table 4.

| Criteria | In-Person | Hybrid | Online |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexibility | Less flexible due to set schedules and location. | Intermediate flexibility. | Highly flexible. Learners can complete coursework at their own pace and schedule. |

| Individualized Learning | Few opportunities, as the course is set by the instructor and is the same for all learners in a cohort. | Intermediate opportunities, with some set content for the in-person classes, and some choice for the content in the online component. | More opportunities to customize the experience for each learner, by choosing a preferred path and specialization through branched pathways in the online course. |

| Costs | Generally, more expensive to offer, due to instructor time. The fixed costs of an instructor are the same, whether there are few or many learners in the course. This means that the break-even costs can be high, and a course will not be offered unless the demand for it is high (many learners register for the course). | Costs vary depending on the amount of face-to-face and online instruction. Generally, the break-even costs will match those of an in-person course, since an instructor must attend every class, regardless of the number of learners who are registered. | Less expensive due to scaling opportunities (i.e., once built, the course can be repeatedly offered with fewer costs). Often, the instructor is paid on a “per learner” basis to answer learner questions and grade assignments, which can decrease the fixed costs of offering the program. This means the breakeven costs are low and a course can be offered even if there is one learner, making it possible to respond to low demand for a course. |

| Interaction | High level of face-to-face interaction with instructors and peers can be engaging. | Moderate interaction with instructors and peers. | Limited interaction with instructors and peers can be less motivating for some learners. |

| Access to Resources | Access to on-campus resources such as libraries, labs, specialized software, and equipment. More opportunities to make a connection with guest speakers and become known to them (i.e., for learners to build their network). | Access to some on-campus resources but mostly online resources. | Access to online resources, such as ebooks, articles, and videos. Easier access to a broader range of guest speakers who can connect with learners via a conferencing platform. |

| Technology | Limited reliance on technology, though some courses may use technology for instruction or assignments. | Moderate reliance on technology, learners are expected to have access to computers and the internet. | Moderate reliance on technology, learners are expected to have access to computers and the internet. High reliance on technology, learners need a reliable internet connection and access to a computer. |

| Learning Style | Best suited for students who learn best through peer interactions. | Can accommodate different learning styles with a mix of face-to-face and online instruction. | Best suited for learners who are self-directed and comfortable learning independently. |

Scheduling

In terms of scheduling, there are two approaches to adult programming. One approach is to create intense (bootcamp) training, where learners are engaged in the program on a full-time basis for a short time, usually a few days or weeks. The benefit of this approach is that working professionals can take time off work (either as vacation or because they are sponsored to attend the training by their employer) and complete the training in a short period. It gives learners the opportunity to focus on their learning. This type of scheduling is possible when prospective learners have sufficient time to plan their attendance (e.g., requesting vacation time or professional development support from their employer, which is sometimes planned a year in advance).

The other approach is to organize the training on a more traditional schedule such as once a week for three-hours. This type of training takes longer to complete and is usually preferred by adult learners who are not supported by their employers to complete the training. They do it on their own time, usually on weekends or in the evenings. This type of scheduling can make it easier for adults to organize their lives around other commitments such as finding child care.

The evidence suggests that in terms of achieving learning outcomes, intensive and traditional courses are equivalent (Scott, 2003).

Work-Integrated Learning

Given the close connection between micro-credentials and the world of work, another key consideration is the setting in which the micro-credential takes place: whether in a traditional classroom or in the workplace. The Suggested Resources section contains information about projects that combine work-integrated learning and micro-credentials.

Seet and Jones (2021) refer to work-integrated learning micro-credentials as “micro-apprenticeships.” In their article, the authors argue that this type of learning can help newcomers rapidly gain short, but authentic, workplace experiences that can help them find jobs in their new country.

LMS Considerations

When choosing a learning management system (LMS) for adult learners, there are several factors to consider. The article by Braunston (2018) explains some of the administrative factors, such as costs, licensing, and internal capabilities to maintain the system. In terms of learning design, here are five important factors to consider:

- User-friendly interface.

Adult learners are typically busy and may not have the time or inclination to navigate a complicated or confusing interface. The LMS should have a simple and intuitive interface that makes it easy for users to access and complete their courses. - Customizability of learner experience.

In competency-based learning, adults proceed at their own pace, repeating a module until they have mastered the competency. An LMS that allows for customization, such as the ability to personalize learning paths or choose different modes of delivery (e.g., self-paced vs. instructor-led) may be important for a micro-credential. - Mobile compatibility.

Many adult learners are on-the-go and may prefer to access their courses on mobile devices. An LMS that is mobile-compatible and can be accessed from smartphones and tablets can provide the flexibility that adult learners need. - Analytics and reporting.

When learners are proceeding at their own pace, it’s important to track progress and measure success. An LMS that provides analytics and reporting features, such as the ability to track progress and monitor learner performance, can help instructors and administrators identify areas for improvement and optimize the learning experience. - Support and resources.

Adult learners may not be familiar with the use of an LMS or with your institution’s organization of courses on this platform. It is therefore imperative to consider designing a short orientation course that helps learners become proficient in its tools and structures. - Export capability.

Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) is a file format for an online course package that can be transferred between LMS systems. Not all LMS use this format to make this possible. As described in the companion chapter Design Considerations: Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector (in the section VCC’s Exploration of LMS Options for Micro-credentials), this could be an important factor to consider when choosing an LMS for a micro-credential.

For additional information about how to create effective and engaging online learning environments, as well as a model for choosing the right technology, readers are directed to Tony Bates’s pressbook Teaching in a Digital Age (2022).

Micro-credential Program Structure

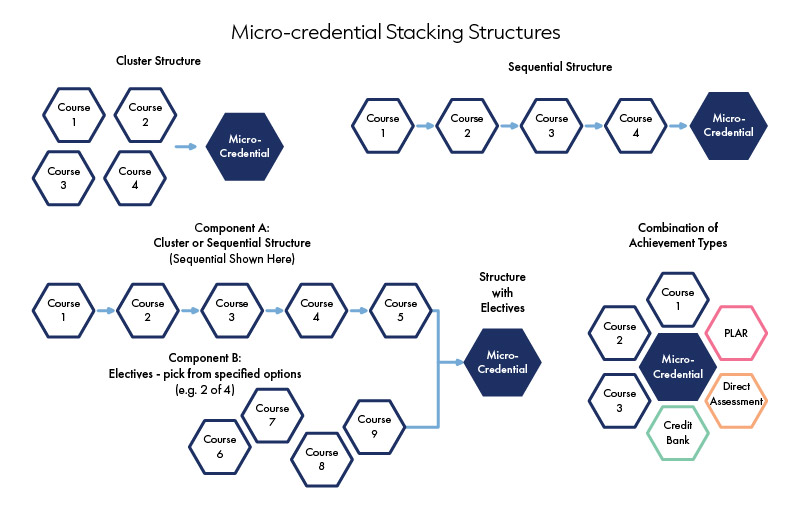

Some micro-credentials are composed of several courses. There are several ways to structure the learner’s progression through the program. These options are depicted in Figure 4 and described below:

- Cluster structure.

This approach allows learners to complete a set of courses in any order, which is useful when the goal is to expose learners to breadth in a field and the courses do not build on each other. An example is the British Columbia Institute of Technology’s Applied Circular Economy: Zero Waste Buildings micro-credential, which requires learners to complete three courses in any order. - Sequential structure.

In this type of program, each course builds upon the previous one, and learners must complete them in a specified order. This is the structure to choose when the goal of the micro-credential is to achieve depth of learning. A curriculum map is particularly helpful when designing this type of program to ensure that the program goals are progressively developed during the sequence of courses. An example is the Capilano University’s Award of Achievement in Data Analysis, where learners must first complete the introduction course, then an intermediate and then an advanced course, and finally a capstone project. - Structure with electives.

This structure requires learners to complete a set of mandatory courses, either in a cluster or sequentially, followed by a prescribed number of courses from a larger pool that gives learners choice in creating their program. An example is the Climate Adaptation Fundamentals Micro-credential offered by Royal Roads University, where learners must complete two core courses (in any order), followed by any two of eight electives. - Combination of achievement types.

In cases where some learners are expected to have prior experience related to the micro-credential, it is possible to unbundle the program and create a flexible program structure that matches the learner’s background and training needs. In this case, prior learning and assessment recognition, credit bank, or direct assessments (see the chapter on Educational Pathways) can help a learner meet some of the program’s learning objectives and the learner achieves the remaining ones through formal education.

The course path through a micro-credential is one element of the program design structure. The other to consider is the scope or size of the micro-credential. For example, in Figure 4, it is assumed that a micro-credential is composed of individual courses. However, it is also possible to stack micro-credentials to create a larger one, which is sometimes called a “milestone micro-credential.”

Some institutions have their own micro-credential framework that specifies different levels of achievement and articulates how one micro-credential might lead to the larger one. For example, Figure 5 shows Capilano University’s micro-credential framework for non-credit offerings, where the different levels of micro-credentials can stack toward the larger ones, making it more accessible for learners.

Curriculum Mapping

When a program is composed of several courses (or when a milestone micro-credential is composed of several smaller micro-credentials), it is important to ensure that by completing each of the constituent courses a learner will achieve the program’s learning outcomes. Ideally, there will also be a progression of skills, with each course helping learners move one step closer to the program’s target goals and competencies.

A curriculum map is a visual tool that captures this information. The data is usually captured in the form of a table where the program competencies are listed as rows and each course is listed as columns. Then, in each cell, the level of achievement expected for each competency for each course is indicated. Typically, the levels are novice, developing, and mastery, or similar terms to indicate progression. Using this chart, it is easy to spot that each competency is achieved by completing all of the courses in the program, and that learners have an opportunity to progress in their skills from the beginning to the end of the program. An example of a curriculum map is provided in Table 2 of the chapter Quality Assurance. Quick guides for creating curriculum maps are available from Dyjur et al. (2019) and McCartin and Tocco (2020). Note that in these guides, the information contained in the rows and columns are switched from what’s described above (i.e., rows list the courses in a program, and the columns list the competencies — either means of displaying the information is acceptable).

The University of British Columbia Okanagan has created an online tool to develop curriculum maps and ensure the design integrity of a program. Curriculum MAP is accessible to anyone in the B.C. public post-secondary sector. An overview of the tool was presented at a BCcampus event and is accessible through the Suggested Resources section.

Evaluation of the Micro-credential

The ADDIE process concludes by evaluating a micro-credential and using the data to improve the next offering of the program. There are two types of data to draw from in evaluating a program: those pertaining to learning design and effectiveness, and those that pertain to the administration of the program.

Kirkpatrick (1998)’s four level model is a standard for assessing the effectiveness of professional development training (Mind Tools, n.d. a). Kirkpatrick outlined how educational interventions can be assessed at any of four levels, which are described below in order of increasing impact, but also of increasing level of difficulty in assessing them.

- Level 1: Reaction.

This level gauges how learners feel about the educational experience. While not an assessment of learning per se, engagement is a prerequisite of learning. Assessing this factor thus serves to diagnose whether there is a foundation for learning. Kirkpatrick was also mindful that employee reaction to a program was often critical in a manager’s decision to continue or discontinue a training program. It is therefore important to collect this data. - Level 2: Learning.

This level assesses whether learners have acquired new knowledge. It does not assess whether they can apply that information. Kirkpatrick recognized that in order to be able to perform a new task, a person must first know — cognitively — how to do it. This is what this step measures. - Level 3: Behaviour.

This level is about demonstrating a competency in context. Can learners translate their knowledge into practice? Can they recognize contexts where and when the new concepts should be applied and use them appropriately? Can they resolve unexpected problems as they try to apply their competencies? This is the focus of competency-based education. - Level 4: Result.

In professional development, the goal of training is usually set at the level of the organization, for example, to improve efficiencies and cut costs. This is what this final level measures. Is the organization operating more efficiently as a result of the training? Is it cutting costs, and if so, by how much? This is the data that provides support that the training was worth the effort.

When engaging in evaluation activity at any of the four levels, there are several potential sources of information to consult:

- The published literature for evidence about best practices;

- Registration and enrollment data to evaluate demand, satisfaction, and persistence;

- Learners can be queried about their experience;

- Instructors can reflect on their observations and offer suggestions;

- Subject matter experts and employers can provide input about the continued relevance and validity of the materials;

- Artefacts submitted by learners, such as assignments, assessments, and grades, can be used to identify what may be clear and/or challenging in the course;

- Learner analytics (i.e., data from the LMS on learner engagement, progress, and performance in the online course) can provide insights into learner behaviour that can be used to improve the course;

- Peers (educators from other departments or institutions) can conduct a review of the course materials (including syllabus, activities, learner artefacts, etc.);

- Educators (such as professionals from the institution’s teaching and learning centre) can conduct a classroom observation, using a classroom observation protocols developed in-house or one that is published (e.g., the Reformed Teaching Observation Protocol (RTOP) to measure teaching effectiveness (Sawada et al., 2000) or the Decibel Analysis for Research in Teaching (DART) to record and automatically categorize the time spent on different activities in a class (Owens et al. (2017)) and to assess the effectiveness of course delivery using established criteria;

- Kirkpatrick’s Level 4: Results can be evaluated through various learner outcomes, including professional accreditation exams, workplace performance, employer satisfaction with newly trained employees, job search success rate, career advancement, etc.

To evaluate the management of a micro-credential, consult staff who administered the program, including those in your unit and those who interacted with your unit in the delivery of the program. Learners may also be able to provide feedback about their experience of navigating program registration, orientation to the course resources, the ease with which they received and used the digital credential awarded, etc. This information can be used to make improvements to the next micro-credential offering.

The Suggested Resources section contains excellent resources for planning the assessment of a micro-credential program.

Suggested Resources

Andragogy Best Practices

Becker, K. L. (2022). Why the “why” matters to adult learners. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/course-design-ideas/why-the-why-matters-to-adult-learners/

Caffarella, R. S., & Ratcliff Daffron, S. (2013). Planning programs for adult Learners: A practical guide (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Crockford, J. (2021). Five tips to creating a more engaging online course for adult learners. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/online-student-engagement/five-tips-to-creating-a-more-engaging-online-course-for-adult-learners/

Doherty, B. (2012). Tips for teaching adult students. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/tips-for-teaching-adult-students/

Gutierrez, K. (2021). 3 Adult learning theories every e-Learning designer must know. Association for Talent Development. https://www.td.org/insights/3-adult-learning-theories-every-e-learning-designer-must-know

Sedlak, W. (2021). How to reach adult students? For starters, talk to them like adults. Lumina Foundation. https://www.luminafoundation.org/news-and-views/insightful-study-shows-how-to-engage-and-enroll-adult-learners/

Sockalingam, N. (2012). Understanding adult learners’ needs. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/understanding-adult-learners-needs/

Team-Based Design Approaches

The following resources describe ways to facilitate a team’s input toward the collaborative design of a curriculum.

IDEO.org. (2015). The field guide to human-Centered design. DesignKit. https://www.designkit.org/

Drysdale, J. T. (2019). The collaborative mapping model: Relationship-centered design for higher education. Online Learning, 23(3): 2019 OLC Conference Special Issue. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i3.2058

Friis Dam, R. (2023). The 5 stages in the design thinking process. Interactive Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/5-stages-in-the-design-thinking-process

Lipmanowicz, H., and McCandless, K. (2019). Liberating structures including and unleashing everyone. https://www.liberatingstructures.com/

Mei, B., May, L., Heap, R., Ellis, D., Tickner, S., Thornley, J., Denton, J., & Durham, R. (2021). Rapid Development Studio: An intensive, iterative approach to designing online learning. SAGE Open, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211047574

Rossiter, D., & Tynan, B. (2019). Designing and implementing micro-credentials: A guide for practitioners. Commonwealth of Learning. http://hdl.handle.net/11599/3279

Young, C., & Perović, N. (2015). ABC learning design method. https://abc-ld.org/

Here are approaches to analyzing the learning outcomes for a course or program to ensure that they cover the complexity of desired outcomes.

University at Buffalo. (2023). Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Curriculum, Assessment and Teaching Transformation. https://www.buffalo.edu/catt/develop/design/learning-outcomes/blooms.html

University at Buffalo. (2023). Fink’s significant learning outcomes. Curriculum, Assessment and Teaching Transformation. https://www.buffalo.edu/catt/develop/design/learning-outcomes/finks.html

DACUM (Guides)

The following handbooks and articles provide instructions for implementing the DACUM process.

Bhattarai, S. (2023). Training manual on DACUM. Colombo Plan Staff College for Human Resources Development in Asia and the Pacific Region. https://pub.cpsctech.org/tm-dacum/pdf.pdf

DeOnna, J. (2002). DACUM: A versatile competency-based framework for staff development. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 18(1), 5–11. DOI: 10.1097/00124645-200201000-00001

Norton, R. E. (1997). DACUM handbook (2nd ed.). Center on Education and Training for Employment. Leadership Training Series No. 67. Ohio State University.https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED401483.pdf

Norton, R. E. (2009). Competency-based education via the DACUM and SCID process: An overview. Center on Education and Training for Employment, The Ohio State University. https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/CBE_DACUM_SCID-article.pdf

DACUM (Examples)

Some examples of DACUM charts can be found in the following sources:

- Halbrooks (2003) used DACUM to create the skills profile for horticultural technology workers. This information was used to revamp Kent State University’s associate degree program.

- Johnson (2010) describes the use of DACUM to develop a curriculum for GIS technicians. The article contains data obtained from each step in the DACUM process.

- Nickbeen et al. (2017) used the DACUM process to address the knowledge and skills needed to engage in green construction, a competency gap identified by the construction industry.

- Ohio State University’s Center on Education and Training for Employment is the home of the DACUM International Training Center. For a modest fee, curriculum developers can access over 65 DACUM charts produced for a range of occupations. These charts can serve as examples or as a starting point for developing a curriculum (though the competencies and tasks in the chart should be locally validated). The Types and Application of DACUM Sample Charts webpage has a selection of examples, including DACUM charts in the areas of:

Resources to Develop Lesson Plans, Activities, and Online Courses

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (2020). Student engagement techniques: A handbook for college faculty (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H., Cross, K. P., (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty (2nd edition). Jossey-Bass.

Bates, A. W. (Tony) (2022). Teaching in a digital age (3rd ed.). Tony Bates Associates Ltd. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev3m/

BCIT. (n.d.). Designing a course. Learning & Teaching Centre. https://www.bcit.ca/learning-teaching-centre/resources/

Brookfield, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2016). The discussion book: 50 great ways to get people talking. Jossey-Bass.

Darby, F., & Lang, J. M. (2019). Small teaching online: Applying learning science in online classes. Jossey-Bass.

Lang, J. M. (2021). Small teaching: everyday lessons from the science of learning (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Multimedia Learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Wall Kimmerer, K. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Competency-Based Education

As part of its capacity-building efforts to support micro-credentials development, BCcampus conducted an online workshop titled Micro-credentials: Competencies at the Core on February 22, 2023. Those who are new to the field of competency-based education are encouraged to view the recordings of this event to familiarize themselves with the concepts. The following two keynote sessions are especially recommended:

- Lena Patterson, program director of micro-credentials and business development at the Chang school of continuing education at Toronto Metropolitan University, delivered a 45-minute session entitled Why are competencies at the core of micro-credentials? in which she defined competencies in a clear and straightforward manner.

- Dennis Green, co-author of the eCampusOntario Open Competency Toolkit, presented a 45-minute session titled What are competencies and competency frameworks?, which picked up where Dr. Patterson’s presentation left off, with a focus on groups of competencies that are necessary to perform a job successfully.

The recommended guide for writing competency statements and creating competency frameworks is the eCampusOntario open toolkit.

Green, D., & Levy, C. (2021). eCampusOntario Open Competency Toolkit. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/competencytoolkit/

The next three resources can help write competency statements.

Braxton, S. (2022). Back to basics: Defining a digital badge taxonomy using cognitive learning and competency frameworks. The Evolllution. https://evolllution.com/programming/credentials/back-to-basics-defining-a-digital-badge-taxonomy-using-cognitive-learning-and-competency-frameworks/

The British Columbia Institute of Technology has developed the following guide to writing competency statements.

University of Victoria. (n.d.) Using competencies. Action verbs. Career Services. https://www.uvic.ca/career-services/build-your-career/using-competencies/action-verb-list/index.php#ipn-action-verbs

This article describes how to develop a competency framework in a step-by-step fashion.

Mind Tools (n.d. b). Developing a competency framework. https://www.mindtools.com/ad66dk2/developing-a-competency-framework

This chapter presents a good overview of competency-based education, including how to design it, how to train faculty, and some administrative challenges of implementing this model of education.

Pluff, M. C., & Weiss, V. (2022). Competency-based education: The future of higher education. In New models of higher education: Unbundled, rebundled, customized, and DIY (pp. 200-218). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-3809-1.ch010

The following three papers used different approaches to collect the knowledge and expertise of competency-based education practitioners. The findings are principles of effective practice.

Cunningham, J., Key, E., & Capron, R. (2016). An evaluation of competency‐based education programs: A study of the development process of competency‐based programs. The Journal of Competency‐Based Education, 1(3), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbe2.1025

Johnstone, S. M., & Soares, L. (2014). Principles for developing competency-based education programs. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 46(2), 12–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2014.896705

McIntyre-Hite, L. (2016). A Delphi study of effective practices for developing competency-based learning models in higher education. The Journal of Competency-Based Education, 1(4), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbe2.1029

In this article, the authors explore the relationship between short-term training and competency-based education. One reason to read this article is that it provides concrete examples, in the form of screen captures, of the student view of an online competency-based course. It conveys how achieving each skill leads to a sense of progression in a course.

Zhang, J., & West, R. E. (2020). Designing microlearning instruction for professional development through a competency based approach. TechTrends 64, 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00449-4

Connecting Competency Communities (C3) is a LinkedIn group that brings together people interested in the creation and management of competency frameworks. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce hosts a monthly webinar series on the latest developments in competency frameworks worldwide. It is a good place to make connections with others engaged in this work.

The following three articles share the experiences of practitioners of competency-based education.

Roth, A. (2015). Competency-based education: What we learned from experience. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2015/7/competencybased-education-what-we-learned-from-experience

Sonnenschein, N. (2016). Balancing pedagogy and assessment in competency-based education. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2016/10/balancing-pedagogy-and-assessment-in-competency-based-education

Weise, M. (2014). Got skills? Why online competency-based education is the disruptive innovation for higher education. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/11/got-skills-why-online-competencybased-education-is-the-disruptive-innovation-for-higher-education

This white paper argues for the creation of a national system of competency frameworks, like those developed in other countries.

Lane, J., & Griffiths, J. (2017). Matchup: A case for pan-Canadian competency frameworks. Canada West Foundation, Human Capital Centre. https://cwf.ca/research/publications/matchup-a-case-for-pan-canadian-competency-frameworks/

Learner Assessment Resources

The following resources are focused on learner assessments and provide ideas and instructions for designing an assessment plan that aligns with learning outcomes of competencies.

Angelo, T. M., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd edition). Jossey-Bass.

Center for Standards, Assessment, & Accountability. (2023). Assessment design toolkit. WestEd. https://csaa.wested.org/spotlight/assessment-design-toolkit/

Conrad, D., & Openo, J. (2018). Assessment strategies for online learning: Engagement and authenticity. AU Press. https://www.aupress.ca/app/uploads/120279_99Z_Conrad_Openo_2018-Assessment_Strategies_for_Online_Learning.pdf