5. Food Systems in British Columbia

Case Study 2: Managing the BC Salmon Fishery

A fishery is a marine environment concerned with breeding and or or harvesting populations of fish and other forms of marine life, such as bivalve molluscs (e.g., mussels, clams). “Fishery” often refers to the area, the type of fish, the method and tools of fishing (including the vessels if any, used in fishing) and the people responsible for stewardship, harvesting and other forms of managing the fishery. BC fisheries are a key natural resource to both the physical and material wealth of the province, yet they are complex environmental systems. While fish are a renewable resource, they are difficult to manage. Estimating populations, as we shall see below, is increasingly difficult due to their mobility, the changing nature of global and localized environmental processes and considerations for other human activity in the region.

Ten thousand years before European settlers arrived in BC, Aboriginal people were sustained by the abundant marine life available along the Pacific Coast and up through the many lakes and rivers. For example, the oolichan harvest was, and remains, an important first spring harvest of fish, coming before the spring salmon runs. Oolichan, rich in nutritionalvalue, was sought after not only as a food but also for the oil that was rendered from it. Oolichan oil was transported along “grease trails,” or trade routes that extended south and east beyond the borders of what is present-day BC, and into southern California, Alberta and Saskatchewan. These same trade routes supported other trade and migration in the area. When European settlers and fur traders travelled west, they did so using Aboriginal guides taking them along the established trade infrastructures that were made for transporting the bounty of Pacific coast fisheries.

The same fisheries that sustained people in the region for the past 10,000 years were also seen as an abundant renewable natural resource by European settlers. With colonization came commercial fishing in a form similar to what we know today. Commercial fishing is the harvesting of wild fish for sale on in the marketplace. It stands in relation to aquaculture, which is the farming of marine life under controlled conditions.

In BC today, there are both commercial fishing and aquaculture industries. Over 80 ocean and freshwater species of fish are traded from BC. This includes several types of salmon, with five species dominating trade: coho, sockeye, pink, chum and chinook. As of 2012, salmon has a declining overall share of the overall seafood harvest.

| Scientific Name | Common Name | Market Name |

|---|---|---|

| Oncorhynchus tshawytscha | Chinook salmon |

Chinook, spring, king |

| Oncorhynchus keta | Chum salmon |

Silver-bright, semi-bright, dark; dog; summer; keta |

| Oncorhynchus kisutch | Coho salmon |

Coho, silver |

| Oncorhynchus nerka | Sockeye salmon |

Sockeye, reds, red salmon |

| Oncorhynchus gorbuscha | Pink salmon |

Pink, humpbacks |

Salmon fisheries in BC, much like other resources, have been subject to technological change and to boom-and-bust cycles related to the global marketplace and food safety. Most salmon are caught in the ocean, which is under federal management. Salmon are anadromous (i.e., they live in the ocean and breed in fresh water), and while the Fisheries Act mandates that the federal government is responsible for both fresh and saltwater salmon habitat, freshwater marine areas are also under provincial management during a key point in the life cycle of the salmon, during their early life and when they return to fresh water to spawn after four years.

Technology has changed the way salmon are fished and prepared, from drying, salting and smoking in the early 19th century and before, to canning, which gained popularity during the 1850s gold rush because of its compact and protected format. In the subsequent 1898 gold rush, authorities required all miners going into the north have 1,100 pounds of provisions.

By the early 1900s, BC was producing 837, 489 cans of salmon a year. This was made possible by the introduction of the Smith Butchery Machine in 1903. A good butcher could remove fins, head, tail and innards from about 2,000 fish per 10-hour day. But the machine could clean 22,000 fish in nine hours, or about 40 fish per minute, drastically increasing production capacity. Changes in marine vessels, on-board refrigeration and the use of radar and sonar all contributed to increased fishing in BC and globally.

Challenges for Management

Salmon return to the same rivers in which they were born to spawn, so each river has its own salmon run. The Fraser River sockeye run is one of the largest in BC. Managing the salmon can be difficult due to mixed demands by industry, First Nations, sport fishers and the need to maintain a sustainable population. Overfishing during the “fish wars” between the United States and Canada has affected the salmon populations, as have competing land use claims.

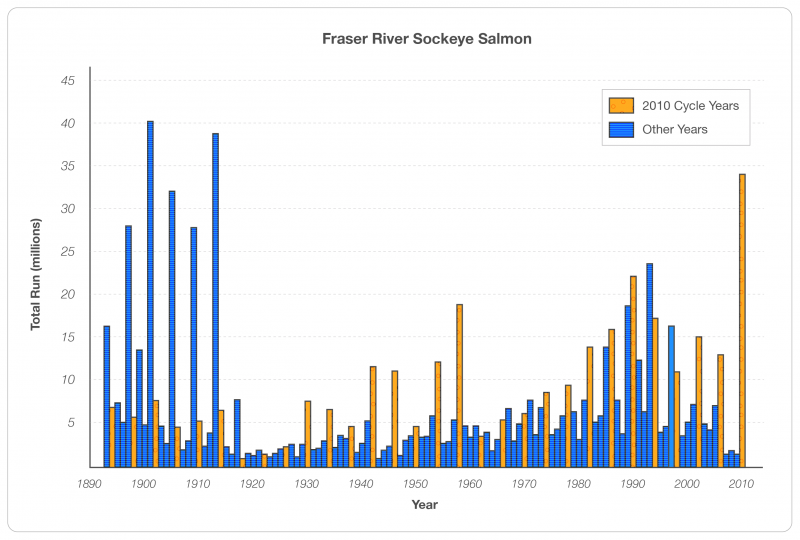

Look at the chart in Figure 1, which shows a drastic drop from recorded salmon runs, which had numbered in the range of 25 to 41 million in the early 1900s to less than 5 million in the years around 1917. Why do you think that is?

The answer doesn’t lie in the mismanagement of fisheries, as you might suspect. Instead, the culprit is the Hell’s Gate slide. In 1912 and 1913, the Canadian National Railway was being built along the steep narrow bank of the Fraser River at Hell’s Gate. Railroad construction necessitated blasting into the rock, which fell into the Fraser River in the canyon below, which contributed to an already steep and difficult passage for the salmon. In 1913, a rock slide occurred in the same place in the season just before the salmon returned to their spawning grounds. As you can see in Figure 1, salmon levels remained staggeringly low until 2010. Despite the significant jump in 2010, the Fraser River run is still recovering from the the 1913 slide, over 100 years ago.

More contemporary threats to the BC salmon fishery include oceans, climate change, fish farming and hatcheries. Oceans house natural predators of salmon, such as seals and sea lions. Mackerel is moving north as waters warm, competing for food sources with the salmon. In the oceans salmon also face over-harvesting in international waters, which is exhibited by the many disputes over salmon harvesting rights. Climate change affects salmon due to warming waters, which are not favoured by salmon, who tend to thrive in colder temperatures.

Salmon Farms

Salmon farms have seen exponential growth since the 1980s. Salmon farming entails raising salmon in net pens, which are stationary in bays or inlets, rather than existing in the open ocean. Fish farming contrasts with hatcheries, which use and maintain freshwater hatching beds to artificially increase salmon production.

In 1984 there were only 10 salmon farms in BC, and five years on, there were 135 farms run by 50 companies. In 2004 there were 129 farms in operation by 11 companies. The spike in farms lead to overproduction, driving the world price of salmon down and increasing environmental and biological risk. From 1994 to 2002, BC put a moratorium on new fish farms, which helps to explain the drop in their number from 1989 to 2004.

Disease transfer is the largest concern of fish farms. Some salmon, such as coho, cannot be farmed because they experience high stress levels due to containment and therefore do not reach maturity. Higher levels of disease among farmed salmon pose a risk to wild salmon populations if the farmed salmon escape and mix with wild salmon populations. Salmon farms use nets to hold Atlantic salmon populations of 700,000 to 1.3 million fish close to the rivers where pink and chum salmon are at their smallest and most vulnerable, and therefore most susceptible to disease transfer. The major solution to the risks of salmon farming is to produce the fish on land in tanks; this, however is a significantly more expensive option.

One of the major biological risks to the salmon population come from sea lice, which are increased by salmon farming. Larvae hatching from sea lice on wild adult salmon migrating into rivers infect the farm salmon in the fall. The close quarters of the fish in the net pens allows the sea lice to spread. Researchers in Norway have found a young salmon or sea trout can bear approximately one louse for every gram of the fish’s weight. Research suggests that at 0.3 to 0.4 grams pink and chum fry are much too small to survive even a single louse.

There are two species of sea lice commonly found on farmed and wild salmon in BC: Gravid Lepeophtheirus salmonis, which are only known to live on salmon and appear to damage juvenile salmon. The Gravid Caligus clemensi can live on many fish species and appears not to damage fish. Sea lice exist in large numbers near fish farms and are virtually absent elsewhere in the ocean.

Summary

As we have seen from this case study, there are many threats to a key resource in our food system. Additionally, it is a complex system to manage between economic and environmental sustainability pressures. Some of the challenges, as in the case of the Hell’s Gate slide, happened over a century ago, and we are still dealing with the consequences.

The Pacific salmon was added to the list of BC’s official symbols in February 2013 (as the fish emblem) in recognition of its huge impact on the environment, culture and the economy. What sort of solutions do you see to help manage the BC salmon fishery?

Attributions

- Figure 5.10 Fraser River Sockeye salmon by Hilda Anggraeni derived from Pacific Salmon Commission (http://www.psc.org/)