Introduction

In sitting down to think about what a regional geography of British Columbia (BC) might look like, the ideas in the room were as diverse as the people there. However, we all agreed on one thing: a traditional textbook format was not something that would fit the scope of the project that we had been set. Regional geography is often considered to be an inwardly focusing geographical perspective with analysis pertaining to local networks and drawing on isolated contextual examples. So what did regional geographies of BC mean to us as a diverse group of geographers?

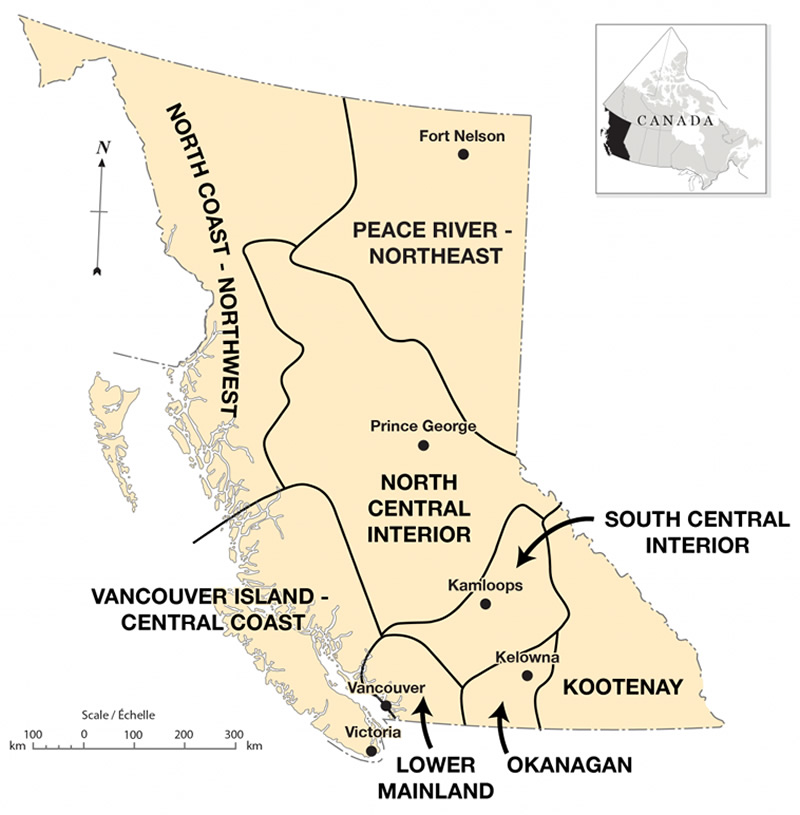

The discussion generated two themes: the first, illustrated by the Regions of British Columbia map (see Figure 1), comes from an understanding that BC is an incredibly diverse place. There are vastly different physical features of landscape, from temperate rainforests to deserts to beautiful boreal forests in the north.

The second theme is the importance of natural resources. BC’s rich natural resources such as forestry, fishing, metals, minerals and natural gas not only provide for a vibrant local economy, but make the province a key part of Canada’s economy in relation to the global marketplace. If you put “British Columbia Canada” into a Google search, you’ll be offered a snapshot of some of the issues relevant here in BC, but whose effects are felt across the globe.

The main scope of the book is, therefore, to apply the fundamental geographical approach of understanding our globally changing world by looking at the local processes. These local processes and events are intrinsically linked to the same processes and events elsewhere. For example:

- Mining and its effects are a global issue and we can see how these unfold in BC.

- The recent apologies to First Nations peoples on the residential school issue are similar to events that have occurred in the US, Ireland and Australia.

- Processes of urbanization, a phenomenon that people all over the globe are experiencing, can be seen in Vancouver with our discussion of the city’s development and its rating as the second-most expensive city in the world to purchase a home.

Geography students, indeed all first-year students, need to know and be able to critically assess their own contexts and environments in order to properly engage with our continually globalizing world.

The People of BC

The story of British Columbia is also one of continuous settlement, from the ancestors of the Aboriginal peoples of BC who crossed the Bering Strait 10,000 to 12,000 years ago to the first settlements along the Pacific coast 5,000 years ago, with inward and southern migration throughout the province. European contact and settlement came relatively late in the “age of exploration” and is a familiar story of people in search of resources.

BC is home to an incredibly diverse population including 203 distinct First Nations and Métis groups. Other Canadians can trace their roots to Europe, Asia, Africa and Middle Eastern descent, and an increasing number of recent immigrants are arriving from places such as India, China and Iran. In 2013, BC welcomed 36,161 international immigrants (Government of British Columbia, 2013). All the stories of settlement connect the land of what is now British Columbia to places elsewhere.

The Book

Chapter 1 Urban Settlement in British Columbia charts urban settlement patterns in BC up to current urbanization trends. The intention is to give students an understanding of how BC has been created through, what Doreen Massey (British social scientist and geographer) calls, a global sense of place. How is it that a place is different from other places? Especially one so connected to the global economy? It is through understanding differences, both within BC and without, that the values and diversity of the province begin to shine through. The case studies contained in this chapter offer insights into contemporary socio-ecological processes concerned with sustainability. In one case study, we look at a history of social planning in Vancouver to see what historic decisions have impacted the city and how economic, social and environmental interests are a series of ongoing complex, and often competing interrelationships.

Chapter 2 Socio-Economics in British Columbia sharpens the focus of social and economic relationships in BC by giving readers a clear understanding of how the global economic success and resulting high quality-of-life indicators are not evenly distributed. While Chapter 1 sets up the settlement story of BC, Chapter 2 grounds the reader with a key perspective that runs throughout the book, bringing in the political economies of place into broader socio-economic processes. Throughout this chapter, readers begin to look at the relationality of a place under complex, socially produced forces. The case study of homelessness in the northern community of Williams Lake and the provincial capital of Victoria show that even a social problem within provincial boundaries does not appear uniform across regions.

Chapter 3 Aboriginal Issues in British Columbia focuses on the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have shaped the landscape, politics and lives of millions of people in BC since European settlement of the province. After a brief look at the diversity of Aboriginal people in BC, the chapter examines the modern treaty process in the province, which has been a key issue affecting land tenure and property rights, relations between Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginals, and the ability to realize a stable and healthful livelihood. The case study in this chapter highlights another historical event with an ongoing legacy: the Indian residential school system that was in place across Canada from the 1880s until 1996. The case study provides a look at the history, implementation and effects both inside of BC and among Aboriginal people across the country. It ends by asking readers to consider how such a systematic abuse of a group of people can be reconciled in relation to ongoing land claims and current inequalities that the system engendered.

Chapter 4 Resources in British Columbia focuses on natural resources in the province, which are a source of wealth and sustenance. The extraction of natural resources from land and waters has allowed BC to hold a key place in today’s global economy. At the same time, intensive extraction processes have threatened the natural environment. Mining non-renewable resources such as gold also threatens ecologies that support food systems, fisheries and forests. The case studies in this chapter pick up on the historical and contemporary realities of mining in BC, and ask readers to think about how these extraction processes are related to their relationship to the landscape.

Chapters 5, 6 and 7 all focus on important resources in BC.

Chapter 5 Food Systems in British Columbia looks at food systems, a key form of sustenance, and brings a holistic understanding of the physical and social production of food in contemporary society. Rather than focusing solely on agriculture as an industry, this chapter considers food systems in relation to broader resource management strategies such as fisheries management, food security and urban agricultural land use patterns.

Chapter 6 Forestry in British Columbia takes an in-depth look at forestry management and the lumber industry as it has worked over time. It closes by looking at a major bio-social issue facing BC’s forests, the mountain pine beetle infestation. In the case study, readers are reminded that there are overlapping factors that contribute to the management of our natural resources, and that even renewable resources can be put into precarious positions despite local stewardship initiatives.

Chapter 7 Health Geography in British Columbia moves away from natural resources and turns its attention to the maintenance of another key resource in BC: its people. It provides a broad overview of the health landscape in BC, focusing on the role of GIS in mapping vast territories of health surveillance. The first case study in this chapter considers acute trauma care in BC by mapping the distance to trauma centres. The second looks at the role of urban “heat islands” that exist in the summer months because of the changes in climate; these heat islands increase health risks in some populations, such as the elderly.

Finally, Chapter 8 Physical Geography of British Columbia looks at the physical makeup of the province. In a more traditional volume, this chapter would be placed first, directly after the introduction. But the authors chose to place it at the end in order to emphasize that the social processes explored throughout the book are always deeply rooted in place.

Also included in this book is an appendix that we hope students and teachers alike will use as a resource for understanding and employing research methods across all areas of geography. As mentioned above, this text is meant to be a dynamic resource, for you, the reader, to add to as you explore deeper into the multiple geographies that BC has to offer.

Attributions

- Figure 1. Regions of British Columbia by Hilda Anggraeni

References

Government of British Columbia, 2013. Welcome BC – Immigration Data, Facts and Trends [WWW Document]. Welcome BC. URL http://www.welcomebc.ca/Live/about-bc/facts-landing/immigration-data-facts-trends.aspx (accessed 6.17.14).

McGillivray, B., 2011. Geography of British Columbia: people and landscapes in transition, 3rd ed. ed. UBC Press, Vancouver.