3.2 Morphemes

If we consider meaningful units in a language, we come to a unit beyond which we cannot derive further meaning. This smallest unit of meaning is known as a morpheme. Consider the word ‘dogs.’ It is composed of two morphemes: ‘dog’ and ‘s’ with the latter conveying the plural number. Here we see that while ‘dog’ can be a free morpheme, ‘s’ cannot. Such a morpheme which always needs to be connected to other morphemes is known as a bound morpheme.

One important issue to keep in mind is that while some words are morphemes, not all morphemes are words. Words can be made up of numerous morphemes. In a sentence such as “Jon found the box to be unbreakable” we know there are seven words. However, we can break that sentence into nine morphemes as: “Jon found the box to be un-break-able”.

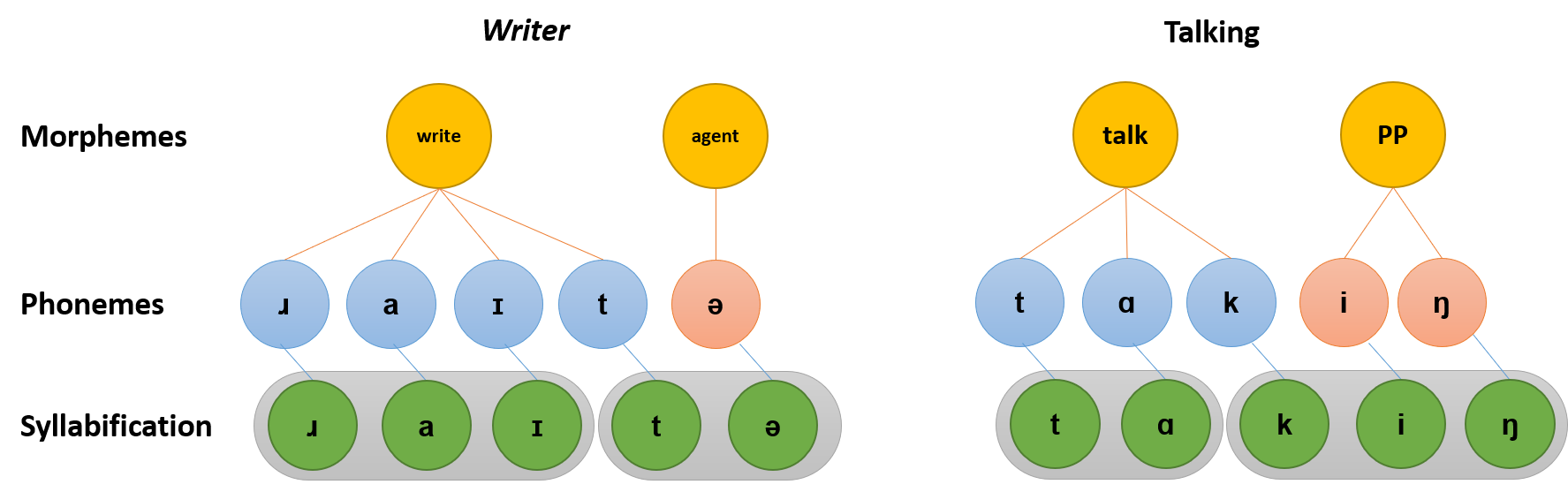

In Figure 3.1 we see examples of free and bound morphemes. The -er and -ing in writer and talking are known as suffixes. These are morphemes that attached to the ends of other morphemes. Examples include the plural suffix -s and the past tense -ed. English also has prefixes as in reheat, invisible and disagree.

Allomorphs

Previously we came across the concept of an allophone. These were variations of the smallest sound unit in a language or phoneme. Similarly, the smallest unit of meaning in a language, the morpheme, can also have variations called allomorphs. These allomorphs often vary depending on the environment. The most common example of this is the indefinite article ‘a’. It comes from the Old English ān meaning one or alone. Gradually, the n was lost before consonants by the 15th century so you get the allomorphs a and an. So, you say ‘a book’ but ‘an apple’. Some allomorphs actually change the form of words due to over analysis. For example, a norange overtime became an orange because people thought the initial n was part of the indefinite article. Similarly, an ekename /iːkneɪm / (from Middle English eke or suppliment) was analysed as a nickname. This time the n in an became attached to the following word.

Another example of an allomorph in English is the plural suffix -s. This comes in three variations: [s], [z], and [əz]. So, after a unvoiced consonants we get [s] as in carrots and books. It is pronounced [z] after voiced segments as in friends and iguanas. It is also pronounced (and written) differently in words such as churches and bushed.

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.1 Examples of Morphemes by Dinesh Ramoo, the author, is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

The smallest unit of meaning in a language.

A morpheme that can stand on its own without being dependent on other words or morphemes.

A morpheme that can only appear as part of a larger expression.

An affix that is placed after the word stem.

An affix that is placed before the word stem.

A variant form of a morpheme.