7.2 A Standard Reading Model

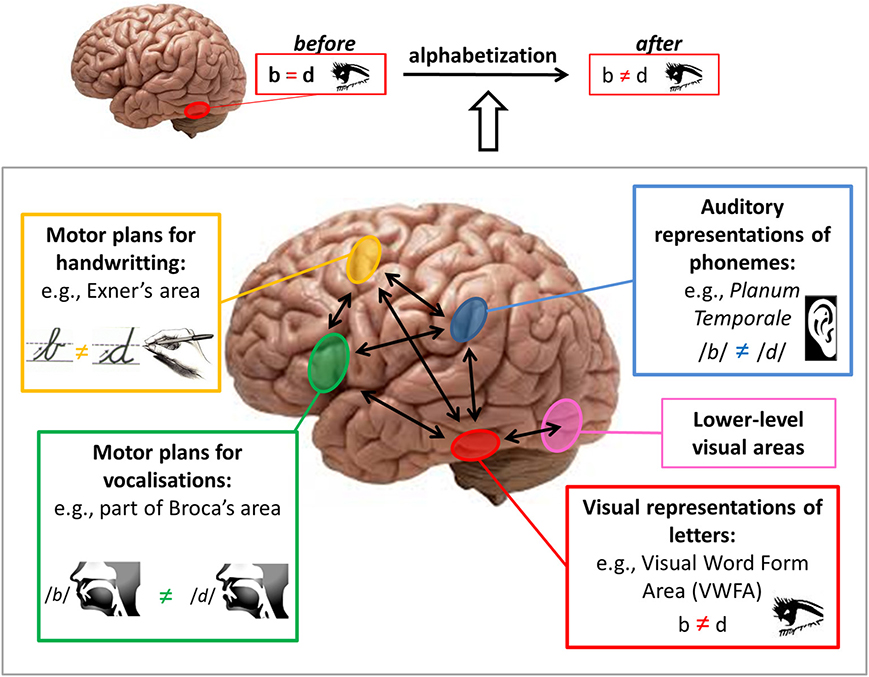

Unlike speech, reading is not a biologically evolved mechanism. Writing emerged in different cultures starting around 5000–6000 years ago unlike speech which may go back as far as 2 million years. Therefore, the mechanisms that we employ for reading and writing would be those which evolved for other cognitive tasks but adapted for this new purpose. As we see in Figure 7.9, various brain regions which evolved to form associations between different modes of sensation and perception have been adapted to engage in reading.

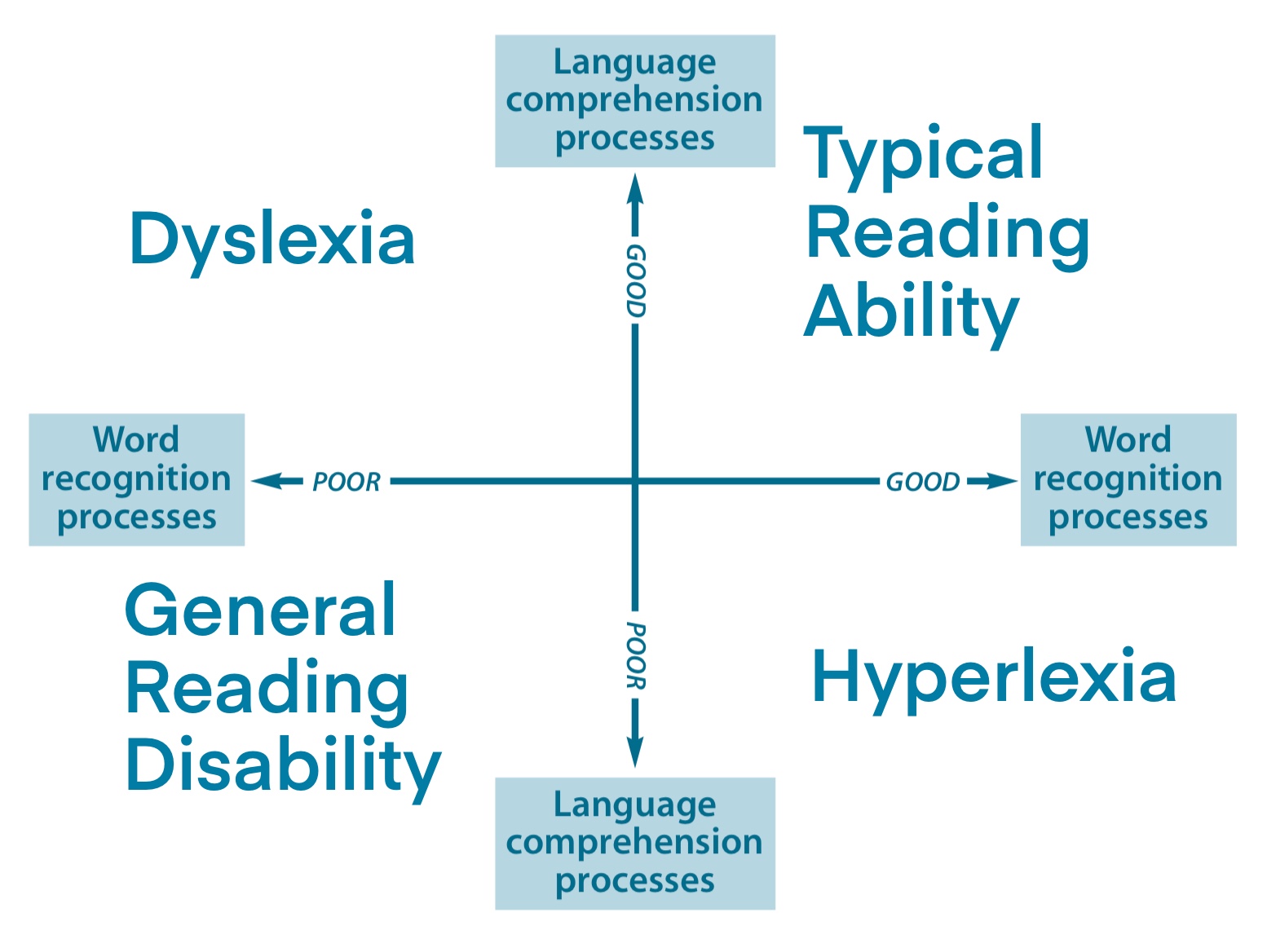

The scientific study of reading is therefore a multidimensional area exploring the everything from the linguistic aspects of reading (as we did in this chapter) to the psychological mechanisms and neural circuits involved. To begin our exploration of various psychological models of reading and the evidence for supporting them, let us start with the Simple View of Reading. This view is based on the idea that reading requires word recognition and linguistic comprehension which need to interact in order for reading to develop (Catts et al., 2016; Savage, 2001). This view also classifies readers into four broad categories: typical readers; poor readers (general reading disability); dyslexics; and hyperlexics (see Figure 7.10).

As we are dealing with a variety of writing systems from around the world, we need to familiarize ourselves with some basic concepts associated with reading. For example, we know that reading requires some way of associating graphemes with phonemes to build meaningful units (words and morphemes). In some cases, this is pretty straightforward in that graphemes map onto phonemes in a regular manner (as in the word “feet”). We don’t need special knowledge to pronounce the word. Even if we were to be presented with a non-word such as ‘pont,’ we don’t need any special knowledge to know how to pronounce them. However, not all words are regular. There are irregular or exception words. Consider place names such as ‘Leicester’ (pronounced /lɛstər/) or surnames such as Featherstonhaugh (pronounced /fænʃɔː/). These are irregular in that the graphemes don’t map clearly onto the phonemes they are supposed to represent. More familiar exceptions would be ‘have’ as opposed to ‘gave.’ English has a plethora of these irregular words which make it difficult for learners of English as a second language.

The fact that we can understand how to pronounce regular words and regularly spelled non-words suggests we must have a mechanism for storing and decoding regular rules for spelling. Our ability recognize irregularly spelled words suggests that there must be another route for retrieving their pronunciation. In other words, there is the suggestion for a dual-route model of reading. The classic dual-route model is based on the assumption of two routes for pronouncing words. There is direct access or lexical route where the word-form needs to be retrieved from the lexicon along with its pronunciation. There must also be a non-lexical route which has a grapheme-to-phoneme converter (GPC) that maps each grapheme to its corresponding phoneme using regular rules (Gough, 1972; Rubenstein, Lewis, & Rubenstein, 1971). The non-lexical route is also evident when children are learning to read letter by letter. In most versions of the dual-route model, whenever a word is encountered, there is a race between the two routes to access the pronunciation. Whichever route gets the final word-form out produces the output. Whether these two routes are necessary for understanding reading is a primary question in most psycholinguistic research. In addition, not all writing systems are the same and may need to employ different strategies for decoding their graphemes. We will explore the evidence for these various models in the next chapter.

Image description

Figure 7.10 The Simple View of Reading

The simple view of reading classifies readers in four broad categories based on the language comprehension and the word recognition. These categories are:

- Typical reading ability: good language comprehension, good word recognition

- Dyslexia: good language comprehension, poor word recognition

- Hyperlexia: poor language comprehension, good word recognition

- General reading disability: poor language comprehension, poor word recognition

[Return to the place in text (Figure 7.10)]

Media Attributions

- Figure 7.9 Brain Areas and Visual Language by Pegado F, Nakamura K and Hannagan T is licensed under a CC BY 3.0 Unported license.

- Figure 7.10 The Simple View of Reading by Smilingpolitely is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 International license.

In the dual-route model, the pathway that processes whole words.

In the dual-route model, the pathway that processes words using grapheme-to-phoneme conversion.

The hypothesized system that converts graphemes into phonemes when reading aloud.