3. The Language of Mental Health

Mental health terms are often used interchangeably or inaccurately. This section introduces the Mental Health Continuum and defines different mental health states so participants can begin to accurately use mental health terms and understand the difference between mental distress, mental health problem, and mental illness.

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading the slide deck, see the Introduction.

In the last 10 years, mental health awareness has increased to a point where we can openly discuss mental health in many contexts. Talking about mental health is an important part of decreasing the stigma associated with mental illness. However, when we are talking about mental health, we often use words loosely and interchangeably so that they can start to lose their true meaning.

We’re going to look at some models to help us understand the language of mental health. Mental health models challenge us to be more thoughtful about how we are using our words. They can help us differentiate between different mental health states: no distress, mental distress, mental health problems, and mental illness.

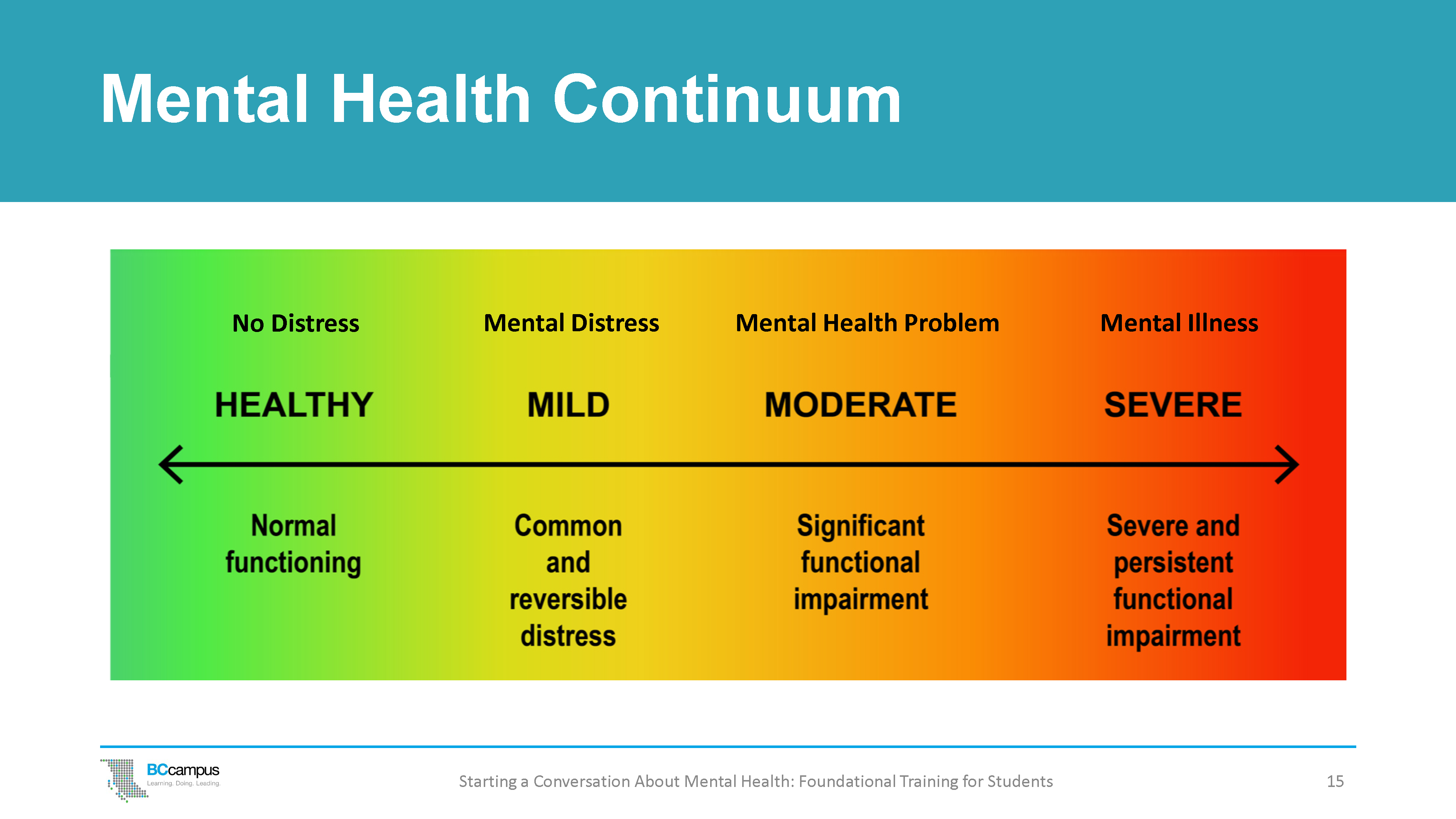

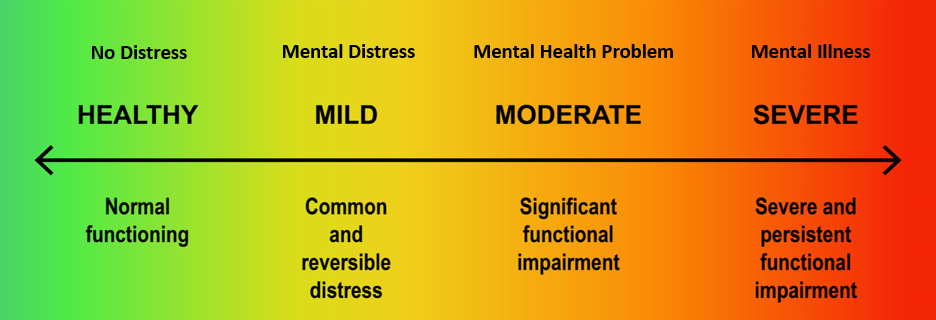

Mental Health Continuum

The Mental Health Continuum is one way to think about mental health. All of us have a mental health life; we all experience changes in our mood, changes in our level of anxiety – from life stressors or from crises – and those changes can be considered on a spectrum or a continuum. On this continuum, we can move from healthier to more disrupted levels of functioning and back. At each level, there are resources available to promote health and reduce disruption.

While it is important to recognize different people’s backgrounds and experiences when dealing with this language, it is crucial that we also recognize that there are a number of words that are specifically reserved for talking about diagnosed medical conditions. The Mental Health Continuum shows four different states: no distress (healthy functioning), mental distress (common and reversible stress), mental health problem (significant functional impairment), and mental illness (severe and persistent functional impairment).

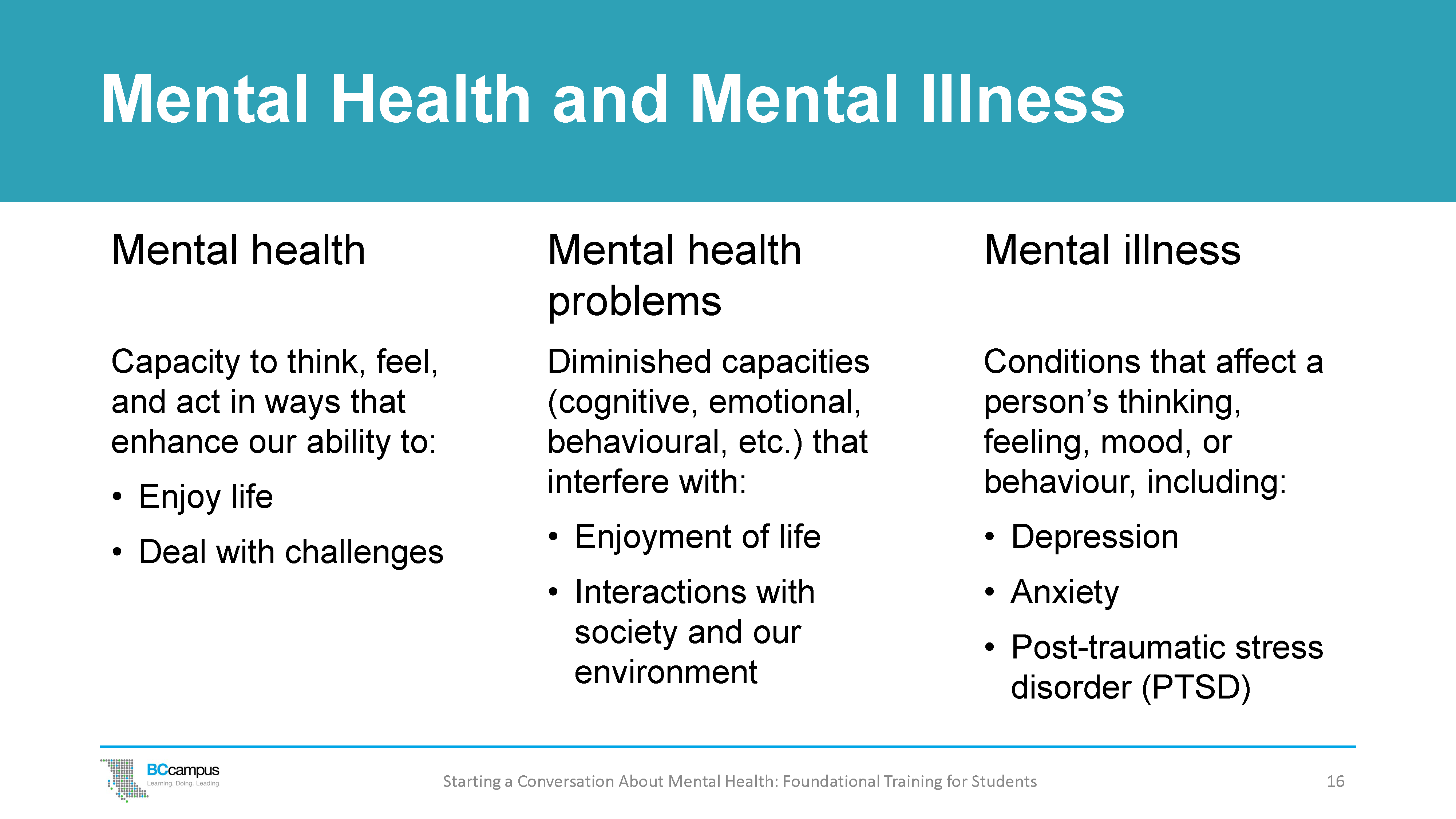

Mental Health Terms

No distress

(Healthy – Normal functioning)

Starting at the left side of the continuum, we see the category No Distress. Most of us are in this state most of the time. This is when we’re having fun with our friends and families, engaging at school or work, enjoying ourselves in a recreational activity, reflecting on the day’s events, or even asleep. We can cope with whatever comes our way, and we can do the things we need or want to do. Thinking back to the Wellness Wheel, this is when everything is mostly in balance on the wheel or in our lives.

Mental distress

(Mild – Common and reversible distress)

When we experience daily mental distress and feel sad, disappointed, angry, or overwhelmed in the moment. These experiences of stress are to be expected at times in our lives; they may be common and reversible, and they are usually temporary, such as the stress we experience during exam time. We can maintain hope that when it’s all over, we’ll likely feel a lot better – the stressor will come to an end and there is usually some relief.

We may not need any intervention; people are often resilient and able to adapt by themselves by engaging positive coping strategies and with support from family or friends. We can share our troubles with others and talk about ways to change the situation.

Mental health problem

(Moderate – Significant functional impairment)

Mental health problems may arise when a person is faced with a much larger stressor than usual. These occur as part of normal life – for example, in response to the death of a loved one, moving to a new country, or having a serious physical illness – and are not mental illnesses.

When faced with large stressors, people can sometimes experience strong negative emotions (such as grief, anguish, or desolation). These emotions are also accompanied by substantial difficulties in other domains, such as:

- Cognitive/thinking – for example, “nothing will ever be the same,” “I don’t know if I can go on in my life”

- Physical – for example, sleep problems, loss of energy, numerous aches and pains

- Behavioural – for example, social withdrawal, avoidance of usual activities, angry outbursts

Sometimes someone experiencing a mental health problem will exhibit noticeable difficulties in everyday functioning. People experiencing mental health problems may need extra help, such as counselling, in addition to support from family, friends, and their community. Medical treatment (medication or long-term psychotherapy) is usually not necessary.

Mental illness

(Severe – persistent functional impairment)

A mental illness is very different from mental distress and from a mental health problem. It arises from a complex interplay between a person’s genetic makeup and the environment in which they live or have been exposed to at different times in their lives.

A mental illness (also called a mental disorder) is a medical condition diagnosed by a trained health professional (such as a doctor, mental health clinician, psychiatric nurse, or psychologist) using internationally established diagnostic criteria. People with mental illnesses will require the best evidence-based care from properly trained health care providers.

The Relationships Between Mental States

The Mental Health Continuum is just one way to help us to differentiate between different mental health states. It’s important to understand the differences because different mental health states should be managed or supported differently.

A person can be in each of these states at the same time. For example, over the course of one day a person can be laughing and having fun with their friends (no distress, problem, or disorder), can experience distress (lost their house key), be experiencing a mental health problem (their uncle with whom they were close died earlier this week), and have a mental disorder (such as depression).

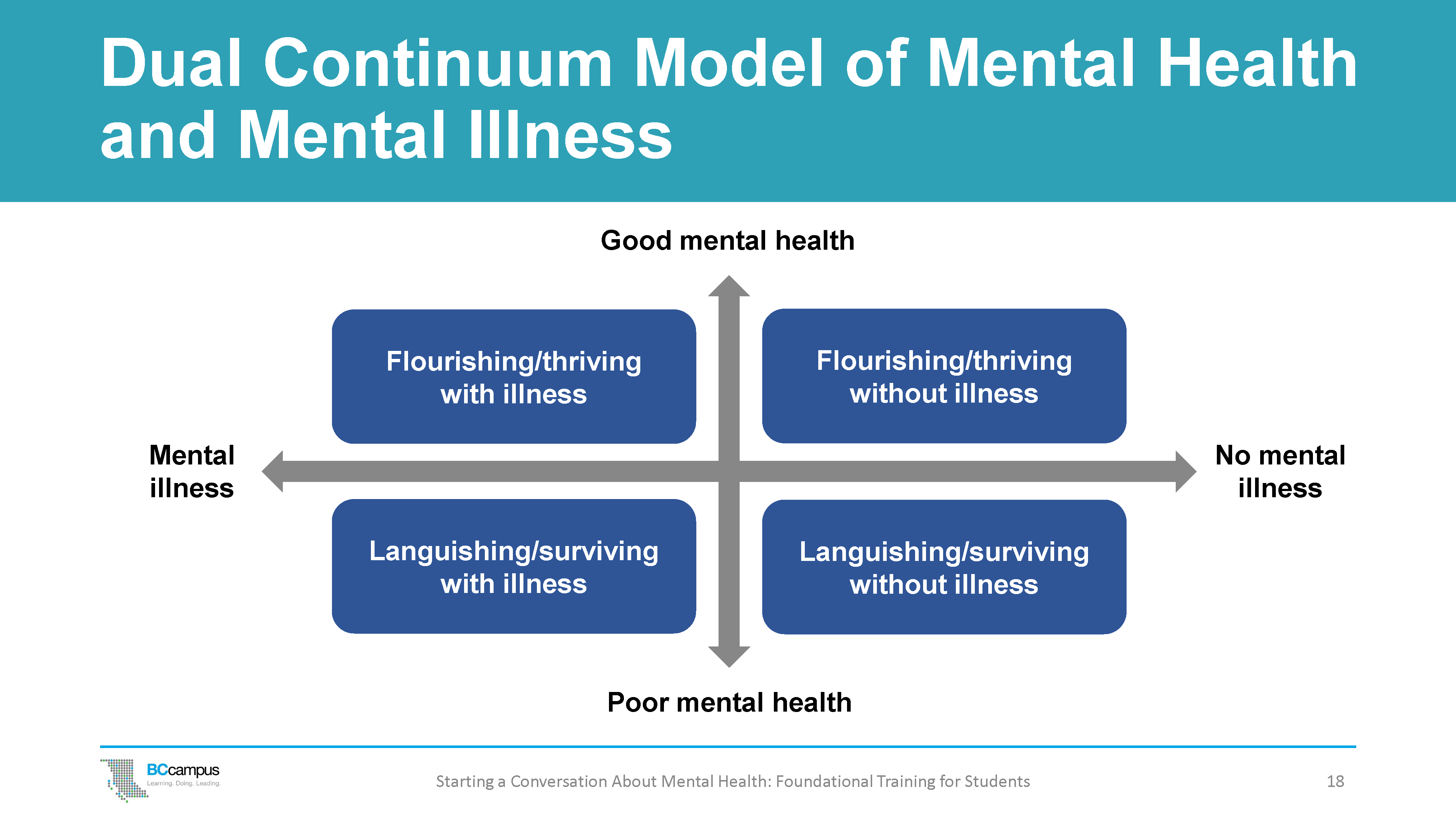

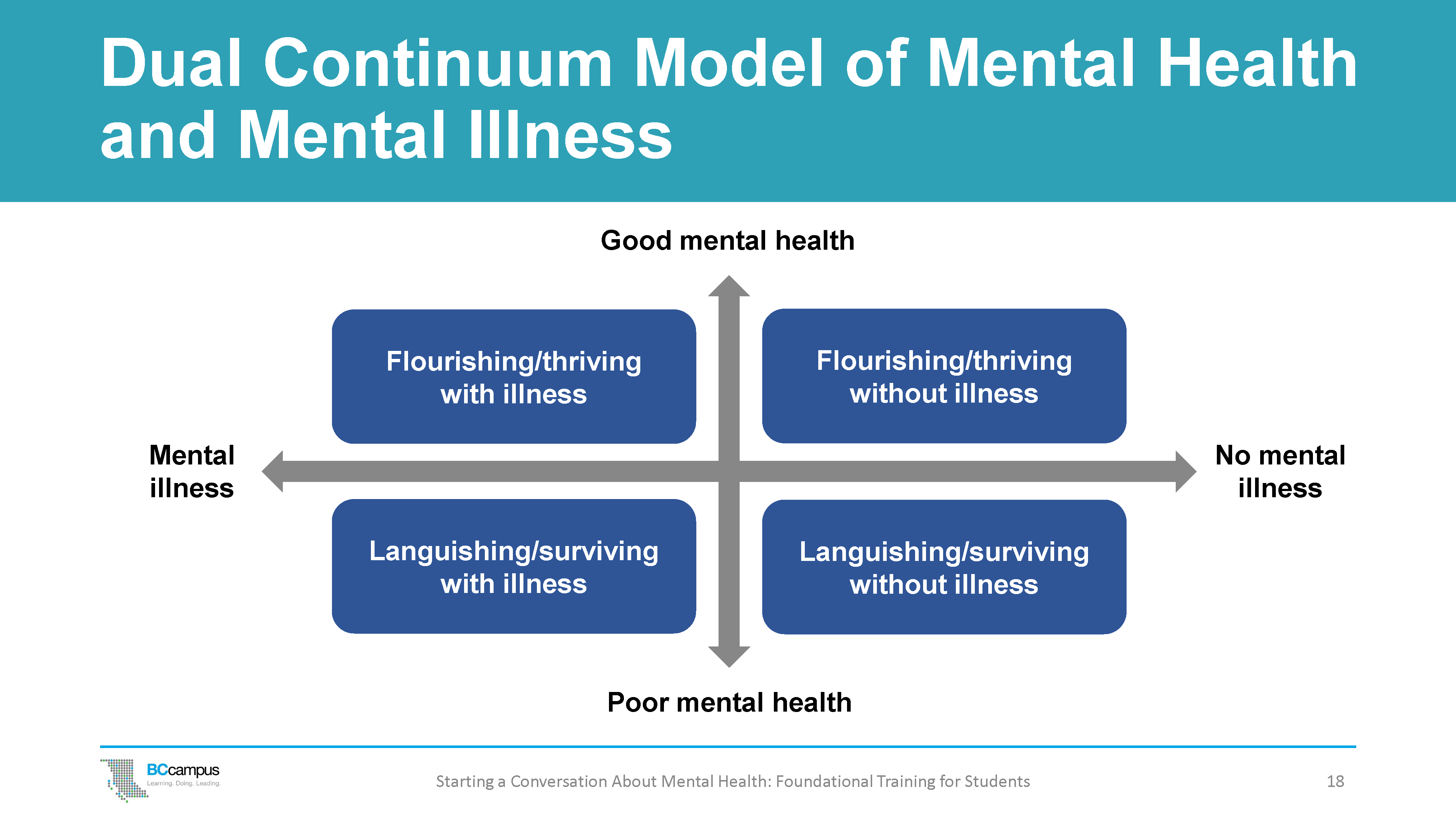

Dual Continuum Model of Mental Health and Mental Illness

Mental health is more than the absence of mental illness. It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It is influenced by many factors, and it affects how we handle the normal stresses of life and relate to others.

The Corey Keyes Dual Continuum Model illustrates how a person diagnosed with a mental illness can have good mental health and be flourishing and thriving. Likewise, a person can be languishing or experiencing poor mental health and not be diagnosed with a mental illness.

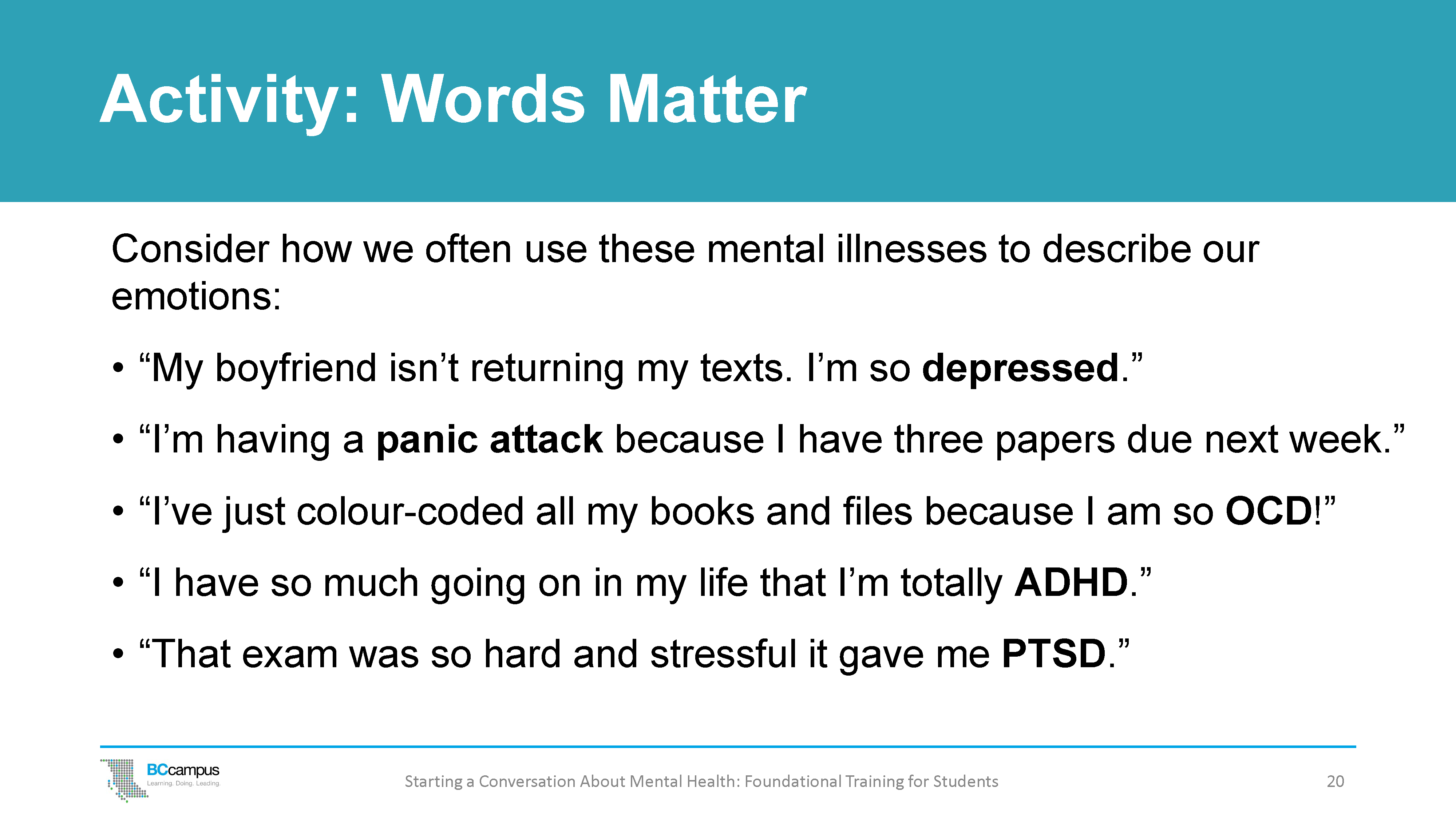

Ask participants to break into pairs or small groups to think about and discuss how we often incorrectly use the mental health terms to describe how we’re feeling.

When we are talking about mental health, we often use words loosely and interchangeably so that they can start to lose their true meaning.

- For example, someone is experiencing a certain level of stress due to an upcoming deadline and they might say, “I’m having a panic attack.” But what does that really mean? Are they actually having a panic attack or are they feeling overwhelmed?

- Using these words when we actually mean that we’re feeling sad, overwhelmed, or nervous can diminish or invalidate the experience of those who live with these clinical conditions.

It can also mean that those seeking help for these conditions may not be able to get the help they need because resources may then be unintentionally diverted to those who are using these words to describe their everyday feelings.

Have each group consider one of the sentences in the slide to discuss how we frequently use mental illness to describe our feelings and emotions.

What are some words we could use instead?

- “My boyfriend isn’t returning my texts. I’m so depressed.”

- “I’m having a panic attack because I have three papers due next week.”

- “I’ve just colour-coded all my books and files because I am so OCD!”

- “I have so much going on in my life that I’m totally ADHD.”

- “That exam was so hard and stressful it gave me PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder).”

Then, have everyone come back together as a large group to discuss how we can be more mindful of the use of these words in common everyday speech despite having precise meanings that are tied to specific clinical diagnoses of mental illnesses.

We need to be careful of our use of words. For example:

- Depression is not the same as having a bad day.

- Having a panic attack is not the same thing as feeling afraid.

- OCD is not the same as being organized.

- ADHD is not the same thing as being hyperactive.

- PTSD is not the same as feeling upset or stressed about an exam.

Common Mental Health Terms and Definitions

Because it is so important to recognize diagnoses for what they truly mean, here is a list of some of the more common terms heard on a post-secondary campus, as well as their definitions. These terms and definitions are adapted from the American Psychiatric Association, 2013 and are based on information from the DSM-5, a manual developed primarily in the United States.[1] Other classification systems for mental health conditions include the ICD (global), the CCMD (China), and the GLDP (Latin America). You may find it helpful to share these definitions with participants after the small-group discussion activity.

anxiety: A type of body signal or a group of sensations that are generally unpleasant, including a variety of physical sensations that are linked with thoughts that make a person feel apprehensive or fearful. A person with anxiety will often also think that bad things may happen even when they are not likely to happen.

anxiety disorder: A group of common mental disorders. People with an anxiety disorder will experience things like mental and physical tension about their surroundings, or apprehension (negative expectations) about the future, and will have unrealistic fears (see anxiety). It is the amount and intensity of the anxiety sensations and how they interfere with life that makes them disorders.

attention deficit hyper-activity disorder/attention deficit disorder (ADHD/ADD): A mental disorder that is usually lifelong and is associated with a delay in the brain maturing and how it processes information. People with ADHD usually have varying degrees of difficulty paying attention, and may be impulsive or over-active, which often causes problems at home, in school, and in social situations.

depression: A term used to describe a state of low mood or a mental disorder. This can be confusing because people may often feel depressed but will not have the mental disorder called depression. Depression is more than just sadness. People with depression may experience a lack of interest and pleasure in daily activities, significant weight loss or gain, insomnia or excessive sleeping, lack of energy, inability to concentrate, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): A type of mental disorder in which people experience persistent unwanted and recurring thoughts (obsessions) and/or persistent and unwanted repetitive behaviours (compulsions).

panic attack: A sudden experience of intense fear or psychological and physical discomfort that develops for no apparent reason and that includes physical symptoms such as dizziness, trembling, sweating, difficulty breathing, or increased heart rate. Occasional panic attacks are normal. If they become persistent and severe, the person can develop a panic disorder.

panic disorder: A person with panic disorder has panic attacks, expects and fears the attacks, and avoids going to places where escape may be difficult if a panic attack happens. Sometimes people with panic disorder can develop agoraphobia (a type of anxiety disorder in which a person fears and avoids places or situations that might cause them to panic and make them feel trapped, helpless, or embarrassed). Panic disorder can be effectively treated with psychological therapies or medications.

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A mental disorder that can happen to people who experience a really scary, painful, or horrific event in which they felt scared or helpless and during which they were in danger of death or severe injury. People who develop PTSD will have flashback memories of or nightmares about the event and will avoid things that remind them of it. For example, if a person was assaulted in a park, they may be too fearful to go to parks and have to find new routes to work. PTSD can be effectively treated with psychological interventions or medications.

Personal Use of Mental Health Terms

Using mental health terms accurately is important, and it is helpful to check in with yourself to ensure that you are using the right words to describe your experience. It is equally important not to make assumptions about others who are using mental health terms, even if you suspect that they are not doing so correctly.

This is because we cannot assume to know another person’s history or experiences that are leading them to use those terms, and we also do not want to apply terms to others that may not accurately fit their experience – for example, assuming someone with depression is simply feeling unhappy or dramatizing minor concerns, or assuming that someone who is having a bad day has depression.

By checking in with your own use of words, you are making a great start at modelling the appropriate use of mental health terms.

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from Mental Health Literacy for Student Leaders © UBC Student Health and Wellbeing staff (CC BY 4.0 License).

Media Attributions

- Mental Health Continuum © BCcampus based on the University of Victoria continuum of mental health, which is adapted from on Queen’s University continuum of mental health and the Canada Department of National Defence continuum of mental health.

- Dual-Continuum Model © BCcampus based on the conceptual work of Corey Keys and a diagram created by CACUSS and Canadian Mental Health Association is licensed under a CC BY-NC license.

- Clear Blue Running Water at Daytime by Leo Rivas is used under an Unsplash License.

- American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™ (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 ↵