Marketing and Launch

Chapter Audience:

Program Managers

Program Managers

Marketing

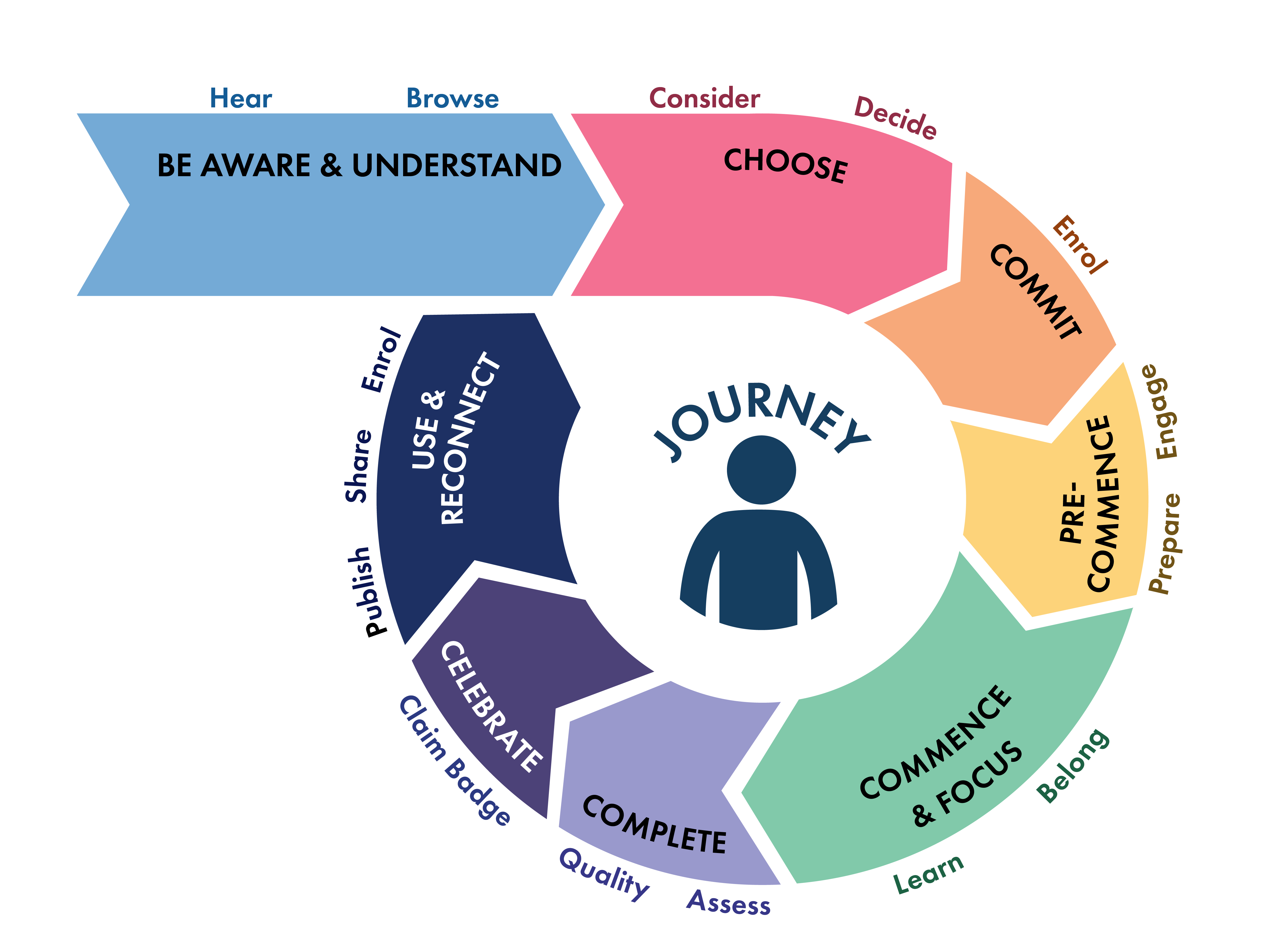

Without marketing and promotion, a new program risks becoming your institution’s best kept secret. While established programs may be able to rely on word of mouth and reputation to recruit learners, new programs must expend considerable resources to raise awareness about the new training among prospective learners and employers. They must also convince their targeted audience that completing the program will be a good investment of their time and money, resulting in tangible outcomes that address their needs. The journey that the learner takes as they move from becoming aware of the training to enrolling and using their new knowledge is captured in Figure 1.

This chapter provides resources for developing a promotional strategy to help facilitate the learner’s journey, particularly through the early stages of becoming aware of and choosing a program. It also presents two approaches for developers to select from for launching their new program.

Timelines

There is a tendency to market a new program only once it is fully developed or nearing completion. The rationale for adopting this approach is twofold. First, it buffers against delays in the development of the program and ensures that there are no false starts. The second reason is that institutions want to invest marketing dollars to generate registrations; if a program is not ready to enroll learners, there is a tendency to view the promotional expenditure as not generating a return on its investment.

Waiting to market a new program once it is developed can work, especially when the institution is well known in a particular field. It is also appropriate when there is a partnership with an organization that has committed to sending its employees to the training and a short marketing period is sufficient to recruit learners.

However, when the micro-credential is new, and in a field where prospective learners may not know to turn to the institution for training, or where there is no built-in pool of registrants, it may be wise to consider promoting the program earlier.

While the program is under development, it is generating content that could be used in its promotion. This content – syllabi, video clips, blogging by the instructor with updates on the course’s development, milestones in registration (e.g., 75 per cent full), interviews with employers helping to develop the program – could be posted on social media. This kind of advance promotion acts as “sneak peaks” that raise awareness and enthusiasm among prospective learners. It also gives them an authentic feel for what the program will provide and who is involved, helping them make the decision to enroll in the program.

Thinking about the program’s promotion could even begin sooner, as early as its inception. In the Using Start-Up Models case study below, Joyce Ip of Capilano University suggests promoting the prospect of a new micro-credential as a way to gauge interest in a program through the response of prospective learners. In other words, promotion and the needs assessment for a new program are merged into a single step.

The take-away from this section is that planning the marketing of a program should go hand in hand with its development.

Envision Your Target

Identify Your Goals

As with any project, it’s best to begin with a clear goal and direct all your efforts toward that target. If your goal is to increase your unit’s reputation in a field, the marketing tactics that you will use will likely be different from those that seek to generate registrations in a particular program.

Ask yourself why you are investing resources in marketing. The answer for most micro-credentials is likely to be that you want to generate registrations. However, there may be other goals as well. For example, your goals may be to:

- Generate excitement for a new program ahead of its launch.

- Obtain a list of prospective learners for your program, as a way to gauge interest in a new micro-credential and to market new programs related to these people’s interests as they become available (in marketing speak, this is called “generating leads”).

- Let the community know that a long-awaited program is now accepting registrations (e.g., a Level 2 training for an existing successful program).

- Increase traffic to your unit’s website, particularly if you offer a suite of related micro-credentials (in other words, the goal of the marketing is not to register prospective learners in one micro-credential, but to solicit the interest of people who might be interested in several programs you offer).

- Raise awareness and educate employers about the merits of a new micro-credential so that they can become allies and endorse the new training.

- Position your program or institution’s reputation as a trusted source and authority in a particular training domain[1].

- Celebrate the success of your program, e.g., by sharing the outcomes of learners who completed the program.

- Attract “repeat customers,” i.e., learners who have taken training from you previously return to refresh their skills and credentials (e.g., to recertify for a credential that has an expiry date).

Create Client (Learner) Profiles

When developing your marketing plan, an important step is to articulate who you are trying to reach and then take steps to gain a deeper understanding of the messages that will resonate with them.

Are you hoping to communicate with prospective new learners, returning learners, employers, or some other group? The messages you craft will be different for each audience.

Identifying your marketing targets is only one step. The next is to research who they are and what they want. Adult learners can be broadly classified into four categories, each with different goals, motivations, and preferences (Eduventures, Inc., 2008; Wiley University Services, 2022):

- 40% are career advancers,

Who are looking for career progression in their field and want their chosen program to be relevant to their work context; - 30% are degree completers,

Who want to finish a degree in order to be agile in the workplace and they want credit for their prior skills and experience; - 20% are career searchers,

Who are looking to change careers and seek mentorship and networking opportunities; - 10% are lifelong learners,

Who are returning to school for personal growth and enrichment and who seek low-cost opportunities to socialize while learning new thing.

Marketers often create client profiles (sometimes called customer profiles or persona) to envision, in concrete ways, the people for whom they are crafting their messages.

As you create your client profiles, consider the following questions:

- Who are they? Consider their demographic characteristics (gender, age, relationship status and whether they have children, industry type, hobbies, geographic location, education, income, daily activities, etc.).

- What is their context or life situation? Are they stay-at-home caregivers? Professionals who travel a lot? Do they ride on transit or in cars? Are they technologically proficient? Who do they hang out with? What is their community?

- Why might they want to take your micro-credential? What matters to them in terms of training outcomes? What factors would they consider in making a training decision? For example, do they want data on employment rates after completing the program? What are some of the contingencies in their lives that might impact their ability to take the program? Which features of your program might appeal to them (e.g., is it offered flexibly online giving them the opportunity to do it wherever and whenever they can devote time to it?). What are their most pressing needs? How do they typically engage with institutions like yours to pursue their education?

- Where do they spend their time? Where might you reach out to them? Do they use social media? If so, which platform(s) do they use? How do they use the internet? Do they frequently visit certain websites? Do they follow specific blogs? Do they listen to podcasts? Do they use public transportation? Do they read the local newspaper? Where do they live? Do you have an existing connection to them? If so, describe it.

Brainstorm answers to these types of questions, but also be prepared to conduct research to ensure your assumptions don’t miss the mark. A short online survey can help generate insights. Some data can also be obtained online in other ways. For example:

- Not sure which social media platform is used by your target audience? Hirose (2022) has a guide with descriptions of the typical user of the main social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, YouTube, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and TikTok).

- Marketing tools on most social media platforms allow you to gain insights into their users’ behaviours, interests, demographics, and connections. You can drill down into the data to learn, for example, how their users interested in a specific topic are distributed across the country or how they break down into certain age groups or employment status. What’s more, some social media platforms allow you to create “look-alike” audiences, which are users of the platform who may resemble the people that already follow you on social media.

- Statistics Canada makes census data available and searchable to aid in your research.

- Canada Post’s Precision Targeting tool offers a wealth of information on Canadian neighbourhoods organized by postal code. You can use the interactive map to learn whether the people living in certain neighbourhoods have children, their level of education, their average income, etc.

The Suggested Resources section of this chapter provides examples and templates to create your client profiles.

Articulate Your Program’s Unique Value Proposition

Once the characteristics of the target learners are known, the next step is to articulate how your program can help them achieve their goals and meet their needs. It’s a way to frame the benefits of the program from the perspective of the learner. Identifying this will help you formulate messages that are tailored to your audience.

Beverley Oliver has developed a framework to help institutions think through the value of a training program for learners (Oliver, 2021). The framework, shown in Tables 1a and 1b, categorizes learners into two groups: those seeking a career advantage and those seeking personal interest learning. From there, the framework guides institutions to consider eight benefits of micro-credentials and two costs for the learners. Working through this framework can help an institution develop messaging about a micro-credential from the learner’s perspective.

| Benefits | Learners seeking | Explanatory comments and questions about a micro-credential |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career advantage | Personal interest | |||

| Outcomes | Knowledge/skills | Includes new knowledge skills or insights that are validated | ||

| Employability | Includes recruitment, promotion, salary, job security | |||

| Certification | Types of attestation | Includes paper, digital certificate, badge, or a combination | ||

| Portability | Is it recognized elsewhere (professionally, geographically)? | |||

| Security | Is the certification tamper proof and verifiable? | |||

| Signalling power | Provider brand | What is the standing of the provider, including in industry? | ||

| Partner brand | If there is a partner provider, what is their standing? | |||

| Interoperability | Micro-credentials | Does it lead to other micro-credentials? | ||

| Macro-credentials | Is it a (credit) pathway or supplement to a qualification? | |||

| Quality and standards | Quality assurance | Is the provider accredited and quality assured? | ||

| Industry-accredited | Is it recognized and accredited by industry? | |||

| Assessment and feedback | Assessment | What is the quantity and quality of assessment? | ||

| Identity verification | Is academic integrity assured? | |||

| Main assessor | Is assessment mainly by educators, peers, technology? | |||

| Feedback | Is formative feedback provided? | |||

| Engagement | With educators | Is formative feedback provided? | ||

| With peers | Is there meaningful engagement with peers? | |||

| With industry | Is there engagement with industry? Career advice? | |||

| Convenience | Flexibility | Scheduled or on demand; synchronous or asynchronous? | ||

| Costs | Learners seeking | Explanatory comments and questions about a micro-credential |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Career advantage | Personal interest | |||

| Financial | Course fee | Financial cost, loan, scholarship, or sponsorship? | ||

| Payment method | Is cost up front or is delayed payment available? | |||

| Temporal | Effort | What is the likely level of effort required? | ||

| Travel time | Fully on-site; mostly on-site; mostly online, fully online? | |||

| Opportunity | Could the learner use this time more effectively elsewhere? | |||

Anderson et al. (2006) caution against making assumptions about what your prospective learners value, and advise that you conduct research in order to understand them and their concerns, constraints, and challenges. They give the example of a paint manufacturer that initially assumed that their customers prioritized low cost in a paint product. However, after conducting research, they realized that paint only accounted for 15 per cent of their clients’ business expenses; the cost of labour was the most expensive element. The company designed a paint that required fewer coats (and hence lower labour costs) and marketed the product as addressing the customer’s true needs. They even priced the paint 40 per cent higher than their competitors. It was a hit because the product’s value proposition resonated with its audience.

If learners have a choice for training between similar programs, the value proposition should also outline what makes your program distinct.

Once you have researched, identified, and prioritized the value of your program for learners, you should capture it in a brief statement that is one to two sentences long. You can think of it as a tag line or elevator pitch. It can be included in your marketing materials (often it is included on brochures, social media posts, and at the top of a program’s web page description).

As you craft your value proposition statement, be sure to include:

- The main benefit of your program (the one that truly matters to your prospective learners and addresses a need or pain point);

- Why your offering is distinct from similar programs.

Here are examples of value propositions from B.C. micro-credential programs:

- “Build confidence in providing care to victims of violence while preserving critical evidence” (from BCIT’s Advanced Forensic Nurse Examiner microcredential);

- “Launch your career as an editor or validate your experience with a respected credential” (SFU’s Editing Certificate);

- “Accelerated entrepreneurship, business administration, and leadership course content tailored to Indigenous individuals, communities, and organizations that partner with our Ch’nook team” (UBC’s Sauder School of Business’s Ch’nook Accelerated Business Program);

- “Understand basic food safety, learn to protect yourself and others from foodborne illnesses and leave with a 5-year certificate” (Selkirk College’s Foodsafe Level 1 certificate);

- “Help expand the potential of people with disabilities by learning to assess, plan, design, and build accessible venues” (VCC’s Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility CertificationTM Training);

- “An award-winning program for recent immigrant and refugee women to learn how to make and sell handcrafted goods at farmers’ markets and craft fairs in Victoria” (Camosun College’s Maker to Market Program).

Know Your Institutional Context

Before you get too far into your marketing plans, be sure to consult your institution’s marketing documentation and policies. Most B.C. post-secondary institutions have them although they will vary in what they are called and their coverage (e.g., here are UBC’s, Langara College’s, and UNBC’s). Your program’s brand will need to align with your institution’s brand, and your marketing will need to comply with your institutional guidelines. The documents may also specify how the institution’s brand assets (e.g., its logo or motto) must appear and how it should be included on all marketing materials.

Develop Your Brand

People often associate “brand” with a logo and a motto or tag line. While a brand does include these elements, they are the output of a discussion about what the product evokes – what it stands for – not the brand itself. Developing your brand means establishing the characteristics of your finished product. For example, do you want it to reflect an edgy program, with a prototype, bottom-up feel that attracts young entrepreneurs? Or, are you looking to create a more polished product that evokes authority, professionalism, and attention to detail that will appeal to mid-career professionals? This should be a discussion with your team and your partners. Once you have sketched out your brand, every aspect of your program – its content and marketing – should reflect that brand.

More information about developing your brand and its importance in attracting learners to your program is available in the Suggested Resources section.

Review Your Assets

Before you shape your marketing strategy, consider taking stock of your financial and human resources, as well as existing communication channels to reach your target audience. This will ensure that you create a plan that is realistic and achievable.

Budget

Determining how much of a new program’s budget should be spent on marketing can seem like a balancing act. On the one hand, marketing is costly, and it can feel like precious dollars spent on resources that are not directly related to the training of learners. On the other hand, if you underinvest in marketing, you may have to cancel the program for lack of registrations. What’s the right amount to put in the budget?

To find out, a first step is to consult people with expertise in marketing post-secondary programs. Consider contacting the marketing department or school of continuing education at your institution. If you are partnering with another organization in offering the micro-credential, your partner may also be able to offer some insights. If similar programs exist at other institutions, consider reaching out to colleagues there to inquire about their budget and experience. These sources may provide a ballpark number to put into your budget as a placeholder.

You can turn to the business world and examine how much they allocate to marketing new products and services. The amount varies by industry (with education usually on the lower end) but it is usually pegged at around 10 per cent of revenues (Business Development Bank of Canada, n.d; Myers, 2021). This translates to between 10 to 25 per cent of the overall budget based on a 2022 survey of 2,937 American companies (Moorman, 2022).

A third option is to draft your marketing plan and then research the cost of each element in the plan. Be sure to build in a contingency for unexpected costs (10 per cent of the budget is a typical number).

What products or services do marketing costs usually cover? Below is a non-exhaustive list.

- Costs for conducting research on your target audience. This could include the purchase of industry reports or providing a monetary token of appreciation to people completing a survey.

- Creation, purchase, and/or design of multimedia assets such as licensing rights to stock images, hiring a photographer to take original photos, hiring a graphic designer to create logos, posting to social media posts, web pages, print ads, pamphlets, etc.

- Paid digital advertising (the cost of embedding your social media posts in your target audience’s social media feeds). These costs can vary widely depending on the channel (e.g., Google Ads compared to Instagram) as well as the aggressiveness of the marketing campaign.

- Traditional advertising, such as newspaper ads, transit ads, print catalogues pamphlets, and radio or television spots. Fees to rent a vendor table at a professional conference.

- Someone to manage digital marketing, including tasks such as optimizing the likelihood that search engines will find your web page when prospective learners search the internet (aka search engine optimization), analyzing the impact of paid digital advertising, and managing social media posts.

- Subscription or access fees to digital platforms to manage social media calendar, marketing analytics, and other tools to manage your marketing campaign.

- Content producers, if the marketing plan includes a content strategy (this means putting out content on social media that not only serves as an advertisement, but also helps to build an audience and shares your expertise on a topic). A possible content producer is the subject matter expert who develops the curriculum. You may consider building this task into their contract.

Team Resources

It may be helpful to take an inventory of the human resources at your disposal before putting together a marketing plan. This will ensure that you draw upon existing knowledge and skills and do not overshoot your ability to execute.

Some of the people to consult include:

- Your team

- Marketing lead. Is there someone on your team with knowledge of marketing? Do they already manage (and are therefore familiar with) your unit’s social media channels? Do they have the time to manage this project?

- Subject matter experts. Are your subject matter experts willing to contribute to marketing the program? For example, are they willing to blog about their progress, post multimedia of draft course content, present at information sessions, etc.?

- Your institution

- Marketing unit. Does your institution have a centralized marketing unit that can provide expertise and support in rolling out the marketing plan for your micro-credential? If so, contact them early to ensure that they have the time and resources to support your project. Their work schedule can fill up months in advance.

- Your partner

- Marketing expertise. Your partner may offer insights about how to reach your target audience (e.g., what industry podcast they follow, or what industry conference or meeting is coming up). They may also have experience in marketing in their industry that could prove helpful.

- Endorsements. Ask whether the partner is willing to publicly recognize the value of your program by endorsing it.

- Approval. If your micro-credential is co-developed and will carry your partner’s brand, get clarity on approval processes. It is likely that they will need to review and approve any communications as a way to protect their brand. Be sure to factor this review period into your timelines and ensure that it is done to maintain a good relationship with your partner.

- Leverage their networks and connections. Your partner likely has existing mechanisms to contact employers in their industry or prospective learners such as their newsletter, website, or social media channels. Inquire whether the partner would be willing to boost your communications on their own channels (i.e., reshare a social media post that you publish).

- Your sponsors

- Approval. Some sponsors require that any promotion bear their logo in recognition of their support for the program. This usually comes with a requirement to consult and get approval before putting out any communication. This must be factored into your timelines.

- Reporting. Do the sponsors require a form of reporting on the marketing for the program and its outcomes? Check early in order to be sure to collect data that aligns with their expectations.

- Alumni and past students

- It may be possible to leverage the outcomes of alumni of your program. For example, consider conducting a LinkedIn search for past learners that display their digital badge for your micro-credential on their profile. You can use such success stories in your communications. Consider reaching out to them to ask for their permission before you develop any communications.

Communication Channels

Finally, review the communication channels at your disposal. These may be ones that you have access to or have used in the past to reach prospective learners. Some ways of reaching your audience may include:

Your own channels:

- Alumni email list;

- Newsletter;

- Existing social media channels, such as LinkedIn or Facebook, which are followed by people interested in what your unit does;

- Website;

- Faculty connected to employers or to current or past learners at your institution.

Your institution’s channels (usually part of the marketing department):

- Social media channels with a larger audience;

- Ability to put out press releases;

- Negotiated discount pricing for purchasing print media advertisements.

Your partner’s channels:

- Newsletter;

- Email list;

- Social media channels targeting people in the industry;

- Website.

Create a Marketing Plan

What Is a Marketing Plan?

A marketing plan is both a strategic and operational document that captures why you are marketing a program (i.e., your marketing goals) and how you plan to achieve these goals.

Why Do I Need a Marketing Plan?

Why should you invest time in writing a marketing plan? There are several reasons. The first is that sitting down and thinking through each aspect of a new program’s marketing will ensure it is complete and each element is aligned. It creates marketing that is deliberate and targeted as opposed to reactive and inconsistent. It also serves as a communication tool for your team so that everyone understands what is being done, why, when, how, and by whom.

It is important to monitor the audience’s response to your marketing tactics and to adjust the plan in light of this data. In addition, situations sometimes change (e.g., the unexpected announcement of a similar program by a peer institution), requiring that you re-examine your strategy. The marketing plan is just that – a plan – and should be viewed as a living document.

How to Write a Marketing Plan

Although there are several models for writing a marketing plan, it typically contains the following elements, many of which were covered in the above sections.

- Goals. What should your promotional efforts accomplish? This was tackled in the section Identify Your Goals.

- Market analysis

- Positioning. Often, this takes the form of a SWOT analysis. A SWOT analysis is commonly used in business for understanding current conditions before deciding on a strategic plan of action. The goal is to identify internal and external factors that are favorable and unfavorable to achieving your objectives. A table is often used to display the information. The table captures your strengths (assets and competitive advantage), weaknesses (things that limit your ability to carry out your plans, such as a lack of resources), opportunities (where do you see that you can make the most headway, e.g., by promoting to a new audience), and threats to your organization in promoting your program (external factors that could impact your plans negatively, e.g., the launch of a similar program or a downturn in the target industry). SWOT is an acronym of these four elements: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Client profiles. A description of the target market, their needs, and what they value.

- Value proposition. A brief statement of what your program offers that will resonate with the target audience.

- Marketing strategy. What approaches will you take to reach your goals? What are the principles guiding your actions? For example, will marketing rely on purchased advertisement? Will it depend on earned media (e.g., someone from your team gives a free lecture on the topic of their expertise and mentions that they are developing the program). In elaborating this section of the plan, you may consider the four Ps of marketing: product, price, place, and promotion.

- Action plan. The actions that your team will take in order to reach your goals. They should align with your strategy. There can be one campaign or several, depending on the scale and scope of your plan. Each one should detail:

- Name of each campaign;

- What is to be done[2];

- When and for how long;

- The budget allocated to it.

- Key performance indicators (KPI). How will you measure the effectiveness of your marketing efforts or the return on your marketing investment? Digital tools make this step easy to do by reporting data on engagement with your posts. It also allows you to set up A/B testing where you carry out marketing campaigns that vary slightly (e.g., using different tag lines on media posts) and monitor the difference in the response to the two strategies (Gallo, 2017). It is also possible to measure the impact of traditional marketing methods by asking prospective learners where they heard about the program when they contact you or register for a program. You should plan when and where you will monitor the impact (e.g., every Monday morning) and revise your marketing plans based on this data.

The Suggested Resources section refers readers to further information for developing a marketing plan and guides for developing a digital marketing strategy. It also provides links to templates and examples.

Promotion Ideas

There are many ways to promote a new micro-credential program.

Traditional marketing ideas:

- Put out a press or news release (see CafePress (n.d.) for instructions on how to write one);

- Write an article or editorial on a newsworthy topic for the local newspaper that is connected to your micro-credential (i.e., “earned media”);

- Purchase a print ad in a local newspaper;

- Develop a pamphlet and use mass mailout to distribute it;

- Use email marketing to promote your new program through your newsletter;

- Advertise on transit (bus shelters, buses, taxies, trains, and ferries);

- Advertise on the radio;

- Pay for an ad campaign using social and/or digital media;

- Use your own social media channels to create engagement (through content marketing) and use the audience to promote your program;

- Create a web page to provide information on your program and serve as a landing page for social, digital, and print advertising.

Strategies specific to the promotion of educational programs:

- Create a splash page for a program before the program is greenlit as a way to gauge interest and decide which programs to develop (see Using Start-Up Models in Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector below);

- Host an information session online or in person;

- Attend an event where your audience will be, e.g., host a booth at a professional conference;

- Provide free public lectures on the topic of your micro-credential to attract an audience of interested people (see UBCO’s Experimentation with Promotional Approaches in Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector below);

- Obtain funding to support free or discounted tuition for the pilot cohort. This group can provide feedback to improve your first offering while spreading news about your program through word of mouth (see UBCO’s Experimentation with Promotional Approaches in Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector below);

- Use tuition discount tactics to encourage registrations, such as early bird specials and package deals (e.g., register for the first two courses in the micro-credential and get the third one for free);

- Promote laddering opportunities in your communications. For example, position the micro-credential as a way for learners to test whether a larger program is right for them (its short duration and cheaper cost reduce the risks) (see BCIT Ladders Micro-credentials into Associate Certificate in the chapter Educational Pathways );

- Search past learner’s digital badges on social media to find success stories about the outcomes of the program.

Launch

Once the marketing has brought learners to your program, it’s time to plan the launch. There are two possible approaches to launching a new program: a soft launch or a splash launch. A soft launch is adopted when the pilot is seen as a prototype. This is typically used when the first cohort buys in to this approach (e.g., if the micro-credential received funding to subsidize the pilot offering’s tuition and the first cohort understands that they are expected to provide feedback to improve the program in exchange for the reduced tuition). A splash launch is used when the content of the course is timely and there is strong institutional support for the program (e.g., the program is linked to a current and public concern for skill shortages in a particular industry). Table 2 compares the two approaches. One approach is not better than the other; choose the one that best fits your situation and needs.

| Soft Launch | Splash Launch | |

|---|---|---|

| Elements | (Common to both types of launches)

|

|

|

|

|

| Benefits |

|

|

| Risks |

|

|

| Suggestion |

|

|

Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector

Using Start-Up Models

At the 2021 Forum of the Continuing Education and Training Association of B.C. (CETABC), Joyce Ip, interim associate vice president of strategic growth, analytics, and continuing studies at Capilano University, presented a session entitled “Start-Up CS: De-Risking Your Program Design by Leveraging the Power of Start-Up Methodology.” Inspired by the book The Lean Startup (Ries, 2011), Ip introduced strategies used by start-up entrepreneurs to safely test whether there is interest and a market for new products. Below, she shares the principles behind some of these ideas.

Interview

How might micro-credential practitioners test interest in a program idea?

“The idea is to test whether there is interest in a micro-credential by collecting real data from the target audience. Institutions can build a ‘splash page’ describing a potential new program before it invests in its development – indeed, even before the program is greenlit.”

“A splash page is a web page that shares information typically provided to learners to help them decide to enroll in a program: title, learning outcomes, scope, target audience, industry opportunities, potential instructors, duration and format, etc. Then, the web page invites visitors to take a small action, perhaps to join an email list to learn more about the program when it moves ahead.”

“By asking prospective learners to act, program developers obtain real-world data about potential learner interest. People don’t just indicate on a survey that the topic sounds interesting; they have left their contact information to keep informed of next steps. This strategy also builds buy-in (by taking action, people invest in the program), spreads awareness about a prospective program, and builds a database of prospective learners to use if the program goes ahead.”

“The approach could also be used for A/B testing (Gallo, 2017). Consider, for example, building two versions of a splash page that describe the program in slightly different ways (e.g., with different program names) to gauge the audience’s response to the two versions. Again, the key is to roll out this kind of marketing strategy early – even before a program is greenlit.”

VCC’s Use of Course Development Materials to Create Promotional Materials

Reflecting on his institution’s experience of developing a new micro-credential, Adrian Lipsett, dean of continuing studies at Vancouver Community College (VCC), realized that a marketing campaign could have started during the program’s development.

Interview

When should micro-credential marketing be planned?

“We typically wait to put up marketing until registration is open. That means we give everybody six weeks to learn about a new program and register. Reflecting back, I see that during the development of the new program we had subject matter experts at our disposal who we could have used to run an information session. Or, we could have posted a prototype of the course content online as a teaser. For example, we could have posted a draft of a short video produced in the workplace as a way to build excitement, showcase the course content, and spread the word much earlier. Institutionally, we are simply not in the practice of applying this tactic. We tend to use social media or online ads to drive registration and avoid expenses that don’t lead to an immediate action. Given how unique each micro-credential is, we’ll likely need to take a new approach to marketing these things and start much earlier. We need to become more proactive and aggressive in our marketing.”

UBCO’s Experimentation with Promotional Approaches

Megan Lochhead is manager of curriculum and academic programs in the Irving K. Barber faculty of science at the University of British Columbia Okanagan (UBCO). As part of her role, she uses her expertise in curriculum design to support faculty and departments as they create new micro-credentials. The faculty has been successful in promoting these new programs. Lochhead shares some of the approaches they have used and the rationale behind them.

Interview

How did you spread the word about these new programs?

“A lot of it comes down to existing networks. For example, professional associations have avenues to inform members of professional development opportunities. Some of our faculty and staff are well connected with these groups and found they were willing to share information with their members, which generated a lot of traction for the micro-credential. Word of mouth is an important strategy to have in your promotional toolkit.”

Did you employ other, more hands-on marketing approaches?

“For our Critical Skills for Communications in the Technical Sector micro-credential, we hosted a series of free webinars to increase awareness about the importance of communication skills because this is not a topic that’s emphasized during a typical bachelor’s degree in science or engineering. We wanted to ensure the link between strong technical communication skills and success in the workplace was on the radar. The webinars were a success, with over 1,000 people participating in the live webinars, and over 2,500 people registering. We saw this as an opportunity to give back to the community by building awareness and creating a learning environment around this topic.”

Where did you promote the free lectures?

“We promoted to our existing networks and professional associations in B.C. We also posted about the event on LinkedIn and Eventbrite. We used the latter to organize registrations to the free events.”

Did you use the email list you collected from these registrations to promote the micro-credential?

“No. We did not request expressed consent to contact participants. Also, the intention of the webinar series was not to generate mailing lists. We saw this as an opportunity to give back to the community and to build a reputation in this area.”

Did the free lectures ladder into the micro-credential?

“No. We didn’t build it that way. However, many participants requested formal recognition of their participation. UBCO has a non-credit credential called a ‘letter of attendance’ that could be used to recognize attendance in a lecture series. We may investigate this further, but we also need to be mindful of the integrity of the credential, if we do so.”

Did you experiment with any other ways to promote this program?

“Yes. In the development of our Critical Skills for Communication in the Technical Sector micro-credential, we asked experts from well-aligned organizations in several sectors to review modules from the perspective of someone working in industry. In exchange, they gained free access to the program for one of their junior employees, who also provided invaluable feedback in this process. We wanted to ensure that we delivered an excellent learning experience that was of value to participants whether they were taking the program to advance in their career, change career paths, re-enter the workforce, or for personal interest.

“About a tenth of the learners in the pilot offering were expert reviewers. In addition to giving us feedback to improve our course, this approach helped to spread news about the program through word of mouth.”

[Note: For more information about this approach (including the template used to collect feedback), see the chapter Employers, Indigenous and Community Partners: Stories from the B.C. Post-secondary Sector and in particular UBCO’s Use of Employers to Review Curriculum.]

Top Tips from UBCO’s Experience

- Give back to the community. Micro-credentials are a great way to extend your institution’s mission. They can build awareness about a subject and contribute to the continuing education of professionals. The UBCO’s free lecture series achieved both of these aims while promoting the new micro-credential.

- Network. Network. Network. Do not rely solely on conventional advertising. Do you have existing connections to your target audience? Consider engaging with them to help spread the word, through straightforward promotion, and by recruiting their input in the development of the program. Creating a network provides an opportunity to share information about micro-credentials and gather input on emerging needs and opportunities.

Suggested Resources

Client Profile

Still not sure how to develop your own client profile? There are many templates available that can direct your efforts. The following is provided in a polished-looking Power Point format along with a detailed article describing its key features and an example. The template is free but the website asks for your email address to gain access.

Matsen, J. (2023). 10 easy steps to creating a customer profile [+ templates]. Hubspot. https://blog.hubspot.com/service/customer-profiling

Developing Your Brand

The following article proposes 10 criteria upon which to evaluate your brand.

Keller, K. L. (2000). The brand report card. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 147. https://hbr.org/2000/01/the-brand-report-card

How do people make purchase decisions? How do you convert them from prospects to learners? In this article, the author argues that staple marketing concepts such as the “funnel” are antiquated in the age of digital media and that customers want on-going relationships with the brands with whom they do business.

Edelman, D. C. (2010). Branding in the digital age: You’re spending your money in all the wrong places. Harvard Business Review, 88(12), 62. https://hbr.org/2010/12/branding-in-the-digital-age-youre-spending-your-money-in-all-the-wrong-places

Marketing Budget

Putting together a marketing budget for a new program can be a daunting task. The following blog post provides a guide, including how much to budget, what to include, examples, and free templates.

Carmichael, K. (2022). Startup marketing budget: How to write an incredible budget for 2023. Hubspot [blog]. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/startup-marketing-budget

Written by and for entrepreneurs, this article explains how to allocate marketing costs for a start-up business. While the costs of acquiring customers cited in this article are quite high, post-secondary institutions would likely incur fewer costs because they are not starting from scratch; they have an established reputation they can leverage to obtain new clients.

Minieri, T. (2022). How much should you spend on marketing. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2022/04/13/how-much-should-you-spend-on-marketing/?sh=30ac6fd258f9

Direct Mail

Canada Post has published a guide to using direct mail (e.g., for mailing pamphlets or catalogues). The guide is free but requires email registration.

Canada Post (n.d.). The essential guide to direct mail. https://www.canadapost-postescanada.ca/blogs/business/marketing/our-essential-guide-to-direct-mail-is-here/

Marketing Plan

The Business Development Bank of Canada has a Marketing Hub where they make resources and articles available to the Canadian business community. This includes an article detailing how to write a marketing plan.

Business Development Bank of Canada (n.d.). How to write a marketing plan. https://www.bdc.ca/en/articles-tools/marketing-sales-export/marketing/5-no-nonsense-strategies-attract-customers

They also offer a marketing plan template. The template is free but requires providing an email address.

Business Development Bank of Canada (n.d.). Marketing plan template. https://www.bdc.ca/en/articles-tools/entrepreneur-toolkit/templates-business-guides/marketing-plan-template

If a marketing plan developed for non-profit organizations is more relevant to your situation, consider looking at the following, easy-to-follow guide to writing a marketing plan for this type of organization.

Network for Good (n.d.). 7 steps to creating your best nonprofit marketing plan ever. https://artsandmuseums.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Nonprofit-Marketing-Plan-Guide-1.pdf

Digital Marketing

The following eBook is an open resource that covers every aspect of digital marketing.

Stokes, R. (2018). eMarketing: The essential guide to marketing in a digital world (6th edition). Open Textbook Library. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/14

Hootsuite has developed a thorough guide to help businesses set up social media marketing campaigns. It includes a step-by-step handbook with resources for every step, including examples, templates, and data to inform decisions about your campaign.

Newberry, C., & Wood, A. (2022). How to create a social media marketing strategy in 9 easy steps (free template). Hootsuite [blog]. https://blog.hootsuite.com/how-to-create-a-social-media-marketing-plan/

Hubspot has also put together a comprehensive guide to social media marketing. It includes information about each social media platform to help businesses decide which is the better platform for them, step-by-step instructions, information on measuring the effectiveness of the tactics used, templates, and examples.

Baker, K. (2022). Social media marketing: The ultimate guide. Hubspot [blog]. https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/social-media-marketing

Works Cited

Anderson, J. C., Narus, J. A., & van Rossum, W. (2006). Customer value propositions in business markets. Harvard Business Review, 84(3), 90 – 149. https://hbr.org/2006/03/customer-value-propositions-in-business-markets

Business Development Bank of Canada (n.d.). What is the average marketing budget for a small business? https://www.bdc.ca/en/articles-tools/marketing-sales-export/marketing/what-average-marketing-budget-for-small-business

CafePress (n.d.) The anatomy of a press release. https://web.archive.org/web/20240712022256/https://www.cafepress.com/cp/learn/index.aspx?page=pr_anatomy

Cancred (2020). Micro-credentialing implementation playbook [revised draft]. Unpublished.

Eduventures, Inc. (2008). The Adult Learner: An Eduventures Perspective [White paper]. https://blogs.bu.edu/mrbott/files/2008/10/adultlearners.pdf

Gallo, A. (2017). A refresher on A/B testing. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/06/a-refresher-on-ab-testing

Hirose, A. (2022). 114 social media demographics that matter to marketers in 2023. Hootsuite. https://blog.hootsuite.com/social-media-demographics/

Moorman, C. (2022). The CMO Survey: Marketing in a post-Covid era. Highlights and insights report. https://cmosurvey.org/results/

Myers, G. S. (2021). How much should I spend on marketing. University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/how-much-should-i-spend-marketing

Oliver, B. (2021). Micro-credentials: A learner value framework. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 12(1), 48 – 51. https://ojs.deakin.edu.au/index.php/jtlge/article/view/1456

Ries, E. (2011). The Lean Startup. Crown Business.

Rossiter, D., & Tynan, B. (2019). Designing & implementing micro-credentials: A guide for practitioners. Commonwealth of Learning Knowledge Series. https://oasis.col.org/entities/publication/e2d0be25-cbbb-441f-b431-42f74f715532

Wiley University Services (2002). Your Marketing Guide to the 4 Kinds of Adult Learners [Infographics]. https://universityservices.wiley.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Adult_Learners_Infographic_FINAL_PDF.pdf

Image Descriptions

The journey starts with:

- Hear, browse

- be aware and understand

- Consider, decide

- choose

- Enrol

- commit

- Prepare, engage

- pre-commence

- Learn, belong

- commence & focus

- Quality, assess

- complete

- Claim badge

- celebrate

- Publish, share, enrol

- use & reconnect

Media Attributions

- Figure 1 Learner Journey was adapted from Designing and Implementing Micro-credentials: A Guide for Practitioners by Darien Rossiter & Belinda Tynan, Commonwealth of Learning, CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- For an example of this, see the blog content for Hubspot and Hootsuite, two social media companies that provide free information on social media marketing. Businesses that want to learn about social media marketing find these web pages and grow to trust the provider. As a result, these businesses may become clients. The two social media companies have thus positioned themselves as trusted brands by making their content expertise broadly available. ↵

- Note: Digital marketing requires considerable work to plan, carry out, and monitor responses, perhaps more so than traditional forms of marketing. It may involve, for example, developing a content calendar that schedules each social media post ahead of time. This is beyond the scope of this toolkit, but readers are directed to the guides and resources for developing a digital marketing plan in the Suggested Resources. ↵