Recognition of Learning

Chapter Audience:

Program Managers

Program Managers Faculty

Faculty

How Micro-credentials Recognize Achievements

When thinking about an official recognition of learning, most people think of the college or university transcript. This is an official document, owned, controlled, and issued by the post-secondary institution, that lists each of the courses taken, and includes one summative assessment of performance for each course (i.e., a letter or percentage grade). Alternatively, people think of the parchment, the printed document that attests that a learner has completed a program at an institution and that describes the date when the program was completed but provides no information on what learning outcomes were achieved or to what degree.

While the completion of some micro-credentials is documented in this way, many record the achievement in an alternative format: a digital badge. Why are many micro-credential achievements documented with a badge rather than (or in addition to) a transcript or parchment?

The first reason is that transcripts and parchments don’t really communicate what a person can do — an important goal of a competency-based micro-credential. A key stakeholder in micro-credential training are employers, and they have a challenging time translating a summative grade for a course (such as a B+) into a meaningful assessment of a prospective employee’s practical skills and capabilities (see the story Role of Competency-based Education in Undergraduate Courses in the chapter Educational Pathways). Employers want a document that describes, in a concrete way, the things that the person has a demonstrated ability to accomplish (Goger & Laniyan, 2022). Ideally, they would also like these competencies recorded in a standardized, machine-readable format, so that software can sift through job applications to identify potential candidates with the desired skills (Barabas & Schmidt, 2016).

There are other reasons for using digital badges to recognize micro-credential achievements. Transcripts may not conform to the needs and expectations of today’s learners, especially when it comes to modularized learning. Learners increasingly want greater control over their education, including how, with whom, and when they share their achievements (Hope, 2019; West et al., 2020). Learners are used to a culture where services are customized to each person’s needs. They curate their own music and video playlists, collating them from several different providers. They want to do the same with their education, customizing their learning journey by taking offerings from different training organizations, curating them in a personalized portfolio, and controlling how they share those portfolios (for example, curating a collection of achievements that showcase a particular expertise) with the people and venues they choose (ContactNorth, 2016; Institute-Wide Task Force on the Future of MIT Education, 2014, p. 13, Moroder, 2014).

Connected to this, and as mentioned in the chapter Educational Pathways, there is increasing interest in recognizing the experience that adult learners bring to their educational journey, which often comes from outside of formal education — in on-the-job training and from non-formal educational providers like massive open online courses (MOOCs) or industry courses such as those offered by IBM, Microsoft, Cisco, and others (Brown & Kurzweil, 2017; Gibson et al., 2016; Jones-Schenk, 2018; Leaser et al., 2020; Lumina Foundation, 2015). These types of educational experiences are not usually captured on a post-secondary transcript, but they could be recognized by a digital badge that is included in a person’s personalized online training portfolio.

Finally, educators may want a more granular way of capturing what learners can do than a summative grade for a course (West et al., 2020). Having the ability to recognize individual skills as they are attained can serve as a pedagogical and motivational tool in the classroom, helping learners see their own progress (Fedock et al., 2016; Iwata et al., 2017). It can also help educators recognize the individualized paths that learners take through a course (see the story UBCO Embeds Micro-credentials in a Freshmen BFA Course in the chapter Educational Pathways). And it can eliminate the need for writing personalized letters of reference to describe a learner’s skills attained in a course, since it could be documented in a record that tracks the achievement of individual skills as a learner progresses through a course.

For all these reasons — the need to capture specific competencies and document learning from formal, informal, and non-formal sources and multiple providers, to make that learning machine readable, and to give control of the collecting and sharing of those competencies to learners — there is vigorous interest and research in identifying alternative forms of learning recognition. The ultimate goal is to provide a deeper understanding of a person’s abilities and learning journey beyond what is captured in a traditional transcript or parchment.

Many formats are emerging to address these issues. Duklas and Bridge (2017) list e-portfolios, comprehensive learner records, complementary records, co-curricular records, and digital badges as some of the alternative credentials currently awarded. Of the range of possible alternative credentials, digital badges are the most popular to capture the achievements of micro-credentials. This is likely because micro-credentials are issued by a range of providers (some that are not post-secondary institutions and do not have ready access to formats like complementary records or co-curricular records), and because their focus on competencies and the ability for learners to control them make them suitable for job applications. According to a 2016 survey, 94 per cent of 190 American post-secondary institutions were already offering alternative credentials, with one in five institution offering digital badges (Fong et al., 2016). Given the explosion of interest in this field, it is likely that this number is even higher today.

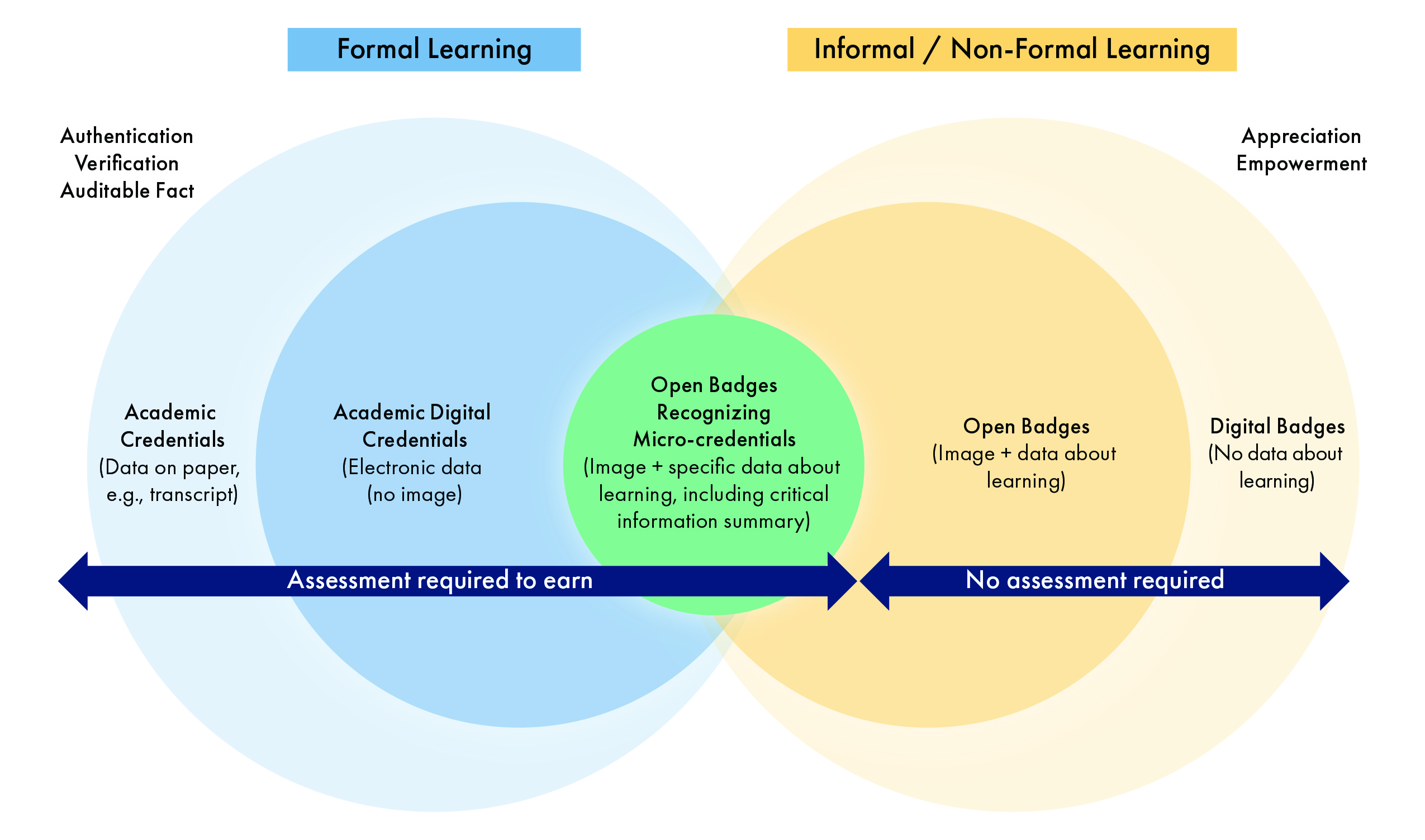

Figure 1 shows the relationship between different types of learning recognition. The ones on the left in blue are the ones typically provided at the end of a formal educational experience. They are issued upon successful completion of rigorous assessments and consist of institution-controlled documents like transcripts. The learning shown on the right in yellow, which typically results from informal or non-formal learning experiences, uses less rigorous assessments, such as attendance and completion. The recognition is awarded through digital badges that the learner controls. Micro-credential programs are earned through a formal assessment process (like academic credentials), but the attestation of learning is more similar to that awarded for informal or non-formal learning experiences. This chapter will describe what a digital badge is, how an open digital badge is a subset of this format, and how micro-credentials are recognized through a format that is itself a subset of open digital badges.

What Is a Digital Badge?

It’s worth beginning this section with an acknowledgement that some of the terms used in this field are still in flux and their definition is under discussion (Weaver, 2021). Notably, in some contexts, and in some resources, the term “digital badge” is used synonymously with “micro-credential.” However, a distinction is emerging, and this is the one that is adopted in this toolkit (University at Buffalo, n.d.; see UBCO’s Development of a New Micro-credential Policy and UFV’s Development of a New Micro-credential Policy).

A micro-credential is the program.

The digital badge is what’s awarded to learners who have successfully completed the micro-credential as evidence of that achievement.

Another way of stating this distinction is to say that a digital badge is to a micro-credential what a transcript is to a degree. The digital badge and transcript are evidence of accomplishments, not the activities that led to earning them.

A digital badge, as the name implies, is digital. It lives online. It is an indicator of achievement or skill that is composed of two elements: an image and its accompanying structured information (its meta-data).

The image is usually a design that conveys visual information about the micro-credential and sometimes the organization that issued it, although there is no standard or rule about the image’s content. Examples from two B.C. institutions are shared in Figures 2 and 3.

The meta-data attached to the digital badge provides information about the micro-credential. It describes the organization that issued the badge and the criteria for earning the badge, and it confirms the information about the person who earned it. The information is embedded in the image itself, but it can be extracted and displayed on a webpage for ease of viewing.

A digital badge “can be displayed, accessed, and verified online” (Iafrate, 2017). To have value, a digital badge needs to be trusted and understood by all stakeholders in the community. Some characteristics are emerging as important to their uptake:

- Portability. Badges need to be transferred and exchanged between institutions and learners. They need to be independent of the platform on which they are stored or viewed. One way to think about it is that it is a file format. In the same way that a PDF is a type of file that can be interpreted and opened by several software, a digital badge is a file type that can be interpreted by many badge platforms.

- Validity and reliability. How does a program demonstrate that it successfully achieves its goals – that its graduates can do the things that the program sets out to teach them? Traditionally, post-secondary institutions have relied on academic accreditation and their reputation to provide evidence of this alignment. However, micro-credentials, with their link to employment, may require more transparency and an external evaluator to confirm the program’s merits (that its goals are relevant to the workplace and its graduates are competent in job settings). Endorsement by employers and professional organizations may become a means of validating a program (Everhart et al., 2016). Such endorsement can be made public and shared as part of a digital badge’s meta-data.

- Data security. To be trusted by the community, digital badges need a means of protecting the integrity and authenticity of the information they contain. This includes protecting against unauthorized access, modification, or duplication of the badge or the data associated with it. Different sorts of badge will lend themselves to different levels of data security, depending on the sensitivity of the information they contain. This can range from ways of authenticating the meta-data (to confirm the identity of the institution, recipient, and badge) to methods for encrypting the data (to prevent unauthorized access or interception).

Who Are the Digital Badge Stakeholders?

There are always several stakeholders in the certification of learning, but these are perhaps more involved in digital badges due to the close alignment of the certification and the world of work, their digital (online) nature, and the de-centralized ownership of the certification itself. Here is the nomenclature used to describe some of the badge stakeholders and their roles (Everhart et al., 2016; Milligan & Kennedy, 2017).

- Badger earner. This is the person who has completed training and/or successfully demonstrated their abilities to meet the requirements for a micro-credential and has earned a digital badge. Once a badge is issued to them, they own the badge and control with whom they would like to share it. Badge earners claim a badge, collect all their badges in a portfolio (also referred to as a backpack or wallet,) and share them with other stakeholders.

- Badge issuer. This is the organization that defined the requirements for earning a micro-credential and assessed each learner’s abilities to meet those requirements. Digital badges make public the contents of a program and the way in which learners are assessed, creating a greater level of transparency for post-secondary institutions than traditional credentials (Jorre de St Jorre, 2020). In issuing a digital badge, they are putting their reputation behind the learner and stating, publicly, that the learner can do the things listed in the digital badge.

- Badge provider. This is an organization that provides the technology infrastructure, knowledge, and support to badge issuers. They create tools to issue, display, and host badges, design online systems that can verify the information contained in a badge, track usage, and create templates that badge issuers can use to create badges that comply with standard badge formats. Often such services are purchased by the badge issuer to host the badges that it creates and issues.

- Badge verifier. This is usually a third party in the learning experience — typically an employer, professional or industry association, other training organization, educator, community or Indigenous partner, or other interested person who would like information about the badge and what it certifies that a person can do. They want to understand the earner’s abilities and need to trust that the badge provides valid information. There is evidence that most employers are currently unaware of digital badges and may need to be educated about them (Perkins & Pryor, 2021).

- Badge endorser. This stakeholder is optional but can lend credibility to a badge. It is a third-party organization that validates that the badge earner, or the badge issuer, or the badge itself, are meaningful and align with their organization’s values. Note here that there are three possible levels of endorsement: the badge, the earner, or the issuing organization. Badge formats and platforms often allow for such granularity of endorsement. This external attestation lends credibility and helps a badge, or a badge earner or badge issuer, gain currency and trust in the community. A badge endorser is putting their reputation behind a badge, earner, or issuer in stating, publicly, that they value and trust the information contained in the badge.

It is worth nothing that the badge issuer, particularly in the context of a post-secondary institution, may involve several units or groups in the organization. For example, it may involve collaboration between the registrar’s office, centre for teaching and learning, school of continuing education, information technology department, marketing team, or other units. Those wanting to issue digital badges should investigate their institution’s policy and procedures for issuing them, which may provide details about the internal stakeholders to contact.

Digital Badge Platforms

Digital badge platforms are cloud-based software that can create, issue, display, curate, share, and authenticate digital badges. Users will interact with digital badge platforms in different ways — using them for different purposes. All users may use the same digital badge platform provider, but the portability of digital badges means that they have the option to use different ones that better suit their needs. Below are the uses and considerations of each of the digital badge stakeholders in using a platform.

Badge Issuers

As badge issuers, institutions need the ability to create badges, store the information contained in them on a platform, and issue them to deserving learners. They can also collect certain metrics, such as the percentage of issued badges that are claimed and displayed. Once a badge is issued and claimed by a badge earner, the institution no longer has control of the badge (i.e., there are no opportunities to fix a typo or change the information). It now belongs to the earner and is under their control. There are many providers to choose from, each offering different features and options. A number of publications explore the range and usefulness of these features and summarize them to help others select the one that best meets their needs (see, for example, Hanafy, 2020; Kiiskilä et al., 2022; and Dimitrijević et al., 2016). In B.C., one of the considerations in choosing a badge platform is that it complies with the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA). Depending on the level of data security required, it is possible to protect the information through block chain technology and give badge verifiers confidence that the data they view has not been altered (Chukowry et al., 2021; Johnson, 2017).

Badge Earners

Badge earners use a badge platform to claim a badge, collect them in a digital portfolio (also called a backpack, passport, or digital wallet), curate and share them with others through digital means such as on social media sites or in a resumé or email. Many social media organizations, such as LinkedIn and Twitter, enable badge earners to disseminate their badges on their sites. Once a badge has been claimed, it resides in the learner’s backpack and is independent of the institution that issued it. Some learning management systems (e.g., Moodle) can serve as a learner’s backpack, though there are also badge-specific options outside of an institution’s learning management system. Many badge platform providers that sell their services to institutions provide access to the student backpack free of charge.

Badge Verifiers

Badge verifiers, like employers, need to access the badging platform to validate and verify the credentials.

What Is the Open Badge Format?

Learners want to be able to curate their learning from multiple providers, be they different post-secondary institutions, massive open online course providers, or industry training. If each institution creates their own method of encoding digital information for a digital badge, learners will have a hard time assembling the different formats. Imagine if a learner tried to assemble a PDF, a Word document, and an Excel spreadsheet, each containing different information. It would be difficult to showcase it all on one platform and in a way that is relatively uniform.

At the same time, learners want to be able to select the platform they will use to collect, curate, display, and share their digital badges — their prefered backpack or data wallet platform. This also requires that the platform “speak the same language” as each of the organizations that issued the badges.

Finally, an employer or verifier will want to view and verify that the badge is legitimate. They will also need a platform that cross talks with the issuers’ platform and the badge earners’ wallet.

In order to enable learners to collect and curate digital badges from any issuer, showcase them on a platform of their choice, and allow reviewers to view and validate the information, a standard format was created to ensure interoperability. It’s called the open badge format. It’s the common way of packaging information about a digital badge that all platforms use to ensure that the information is readable across all systems (i.e., that the badge issuer, badge earner, and badge verifier platforms all “talk” the same language).

The open badge standard is free to use and is the most widely used digital badge format. It was developed as a community effort by Peer 2 Peer University, the Mozilla Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation in 2011. As interest in the open badge format grew, the Mozilla team founded the Badge Alliance in 2014 as a way to foster discussion within the community of users. In 2017, the IMS Global Learning Consortium took over responsibility for continuing the development of the open badge format (IMS Global Learning Consortium, 2022). Note that the open badge format continues to evolve, with new categories of information added based on the needs of the community. In 2018, for example, the version Open Badges 2.0 made it possible to add external endorsement to the open badge meta-data.

Some fields in the open badge format are machine readable, meaning that its possible input are restricted. This makes it possible for the information to be readily scanned by a computer when an employer is searching for a particular type of applicant. Other fields are not machine readible; they are human readable. The format of the information in these fields is not as tightly defined. Often these fields consist of a URL, which are links to another webpage where the information can take on any format. This gives badge issuers more flexibility in the information they add to the badge. The flip side is that this data, by not conforming to a standard, cannot be searched and indexed by a computer as easily. Thus employers are less likely to use these fields in automatically assessing a large pool of applicants.

The open badge format requires that a badge have information on three things (Crytzer & Gance, 2018; Everhart et al., 2016):

- Badge issuer

This is the organization that awarded the badge to a learner. To satisfy the reqirements of the open badge format, this category includes:- Name of the issuing organization;

- Unique internationalized resource identifier (IRI) for the organization;

- URL of the organization;

- Information about the type of organization;

- Description of the organization;

- Optional information includes:

- Image (such as the logo) representing the organization;

- Email of a contact at the organization;

- Endorsement by another organization (here the endorsement refers to the post-secondary institution as a whole, not a specific badge).

- Badge class

The section defines a particular badge (i.e., the recognition for succesfully completing a specific micro-credential program). It is linked to the information above about the badge issuer. It can be awarded to more than one badge earner. It includes the following information:- Badge name;

- Short description of what the badge represents;

- Unique internationalized resource identifier (IRI) for the badge;

- Information about the type of badge;

- Badge image, listed as a URL to the image;

- Criteria for earning the badge, provided as a URL to a webpage. The information on that webpage is human readable, not machine readable, and allows a badge verifier to see more information about what was done to earn the badge.

- Optional information includes:

- Alignment, provided as a URL to a webpage. This information resides on another webpage and is meant to be human readable, not machine readable. It could contain information about the standards that the badge aligns to, such as a specific competency framework.

- Tags that describe the badge and the type of learning it represents (think of a hashtag used to categorize information and make it searchable);

- Endorsement by another organization (here the endorsement refers to the specific badge).

- Badge assertion

This section is specific to the learner who earned the badge. The information in this section is linked to the above two. This section contains the following information:- Recipient — name of the badge earner;

- Date on which the badge was issued;

- Information that allows the badge consumer to authenticate the infomation;

- Optional information includes:

- Evidence of the work done by this learner to earn the badge, provided as a URL to a webpage. This could be, for example, a link to the badge earner’s ePortfolio or digital product such as a video they created as part of their coursework. This information resides on a separate webpage, is human readable (not machine readable), and gives concrete examples of the learner’s abilities.

- Expiry date for the badge, if the skills need to be refreshed or new competency standards are expected to come into effect on a certain date;

- Endorsement by another organization (here the endorsement refers to the learner, not the badge or post-secondary institution).

An overview of the endorsement function added to the Open Badge 2.0 version can be found in an article by Hickey (2017).

The development of the open badge format achieved four main objectives:

- Interoperability. As outlined above, when different internet tools and platforms use a common format for a digital badge, they can exchange information and cross-talk. This means that dedicated badge platforms can share information with learning management systems, social media platforms, and blogs, and each system knows how to interpret the information contained in the badge file.

- Portability. This feature is related to interoperability but focuses on the ability to move data easily between one platform to another — a critical component of digital badges since they move from the control of the institution to the control of the earner, who can then share the badge with others on digital platforms.

- Verification. To trust digital badges, employers and other badge verifiers want the information that they obtain in a digital badge to be accurate. They want a system that automatically checks that the digital badge is still valid (i.e., it has not expired or been revoked), that it was issued by the expected organization (i.e., that a person is not claiming a fake badge), and that the person claiming it was the person who earned it. The open badge format provides some of this authentication. The verification happens when a badge earner claims a badge and imports it into their digital wallet and when a badge verifier calls up the information of a badge. It’s not a perfect system. For example, the system might not pick up a situation where the badge issuer, creator, and earner are the same entity, but future developments of the format might address such loopholes.

- Common usage. Adopting a common format — a set of basic information that all digital badges contain, formatted in an agreed upon manner – ensures that members of the learning and training community have a shared language and can quickly access, understand, and verify the information that digital badges contain.

Critical Information Summary (Meta-Data Manifest)

The open badge format provides guidance and consistency in terms of what information to include in a digital badge and how to structure it. This ensures that each badge contains at least the minimum amount of information that users need to vet a badge.

However, some of the fields give badge issuers greater flexibility in what they choose to share and how they share it. This is especially true of the human readable fields. For example, the open badge field that captures the criteria for earning a badge is simply a link to a webpage where badge issuers can provide additional information in a format of their choosing. The open badge format does not specify how such details should be shared. Remember that the open digital badge format is meant to be used for more purposes than simply recognizing the completion of a micro-credential. It could be used to recognize any form of accomplishment with varying degrees of formality and assessment. A badge could be awarded, for example, for simply attending a webinar. This is why the open format is not prescriptive for the fields describing a program’s content.

Micro-credentials are a more rigorous form of education, and as such, they demand more details about the learning that took place, its delivery format, the learning outcomes it targeted, the competencies achieved, as well as how they were assessed. There is a need to create a standardized way to display the micro-credential’s information. This will help users understand the information more easily. Without it, there will be a degree of inconsistency in how a micro-credential is defined in an open badge format. For example, Lau (2021) describes the different ways in which six Ontario post-secondary institutions embed their micro-credential information in the badges’ meta-data.

There is currently no standard way to capture and display this micro-credential-specific information in an open digital badge. The global micro-credential community has recognized this and it is an active area of work. The first attempt at creating a standard for the Criteria section of the open badge format was made by noted micro-credential scholar Beverley Oliver (2019) (see Table 3 of that document), who called it a critical information summary (sometimes called a meta-data manifest). Soon after Oliver suggested this structure for the Criteria field, several other organizations built on it, adopting it as the standard in their jurisdication (e.g., the Australian Government’s National Microcredentials Framework (2022, p. 3); the European Union’s standard elements (Orr et al., 2020; European Commission, 2021; Council of the European Union, 2022)). The eCampusOntario Micro-credential Toolkit (2022) suggests including a set of critical information in the badge of a micro-credential that aligns with this information. And on his blog, Don Presant (2023) has collated information from several sources to propose a model for the Criteria field of the open badge format that also aligns with this model. Thus, while there is no international standard, there is clear alignment and most thinkers agree on the information to include in the Criteria section of the open badge format.

While there is no formally accepted critical information summary standard in B.C., one is emerging. A group of B.C. institutions are piloting a credit bank for Ministry-funded micro-credentials that would allow learners who earn these credentials to have their learning recognized as PLAR credit at other institutions (see TRU’s Experience with the Credit Bank in the chapter Educational Pathways.) As part of this pilot, the workgroup developed a critical information summary inspired by Oliver’s (2019) work that would contain the information required to inform inter-institutional micro-credential recognition and transfers. A draft of the emerging B.C. micro-credential critical information summary is shown in Table 1a and 1b.

Using the critical information summary developed for the pilot micro-credential credit bank advisory group is likely to result in the province-wide adoption of a model that allows for easier communication across institutions.

To ensure consistency across all digital badges issued by an institution, each institution may wish to establish other (institution-specific) standards such as criteria for the design of the digital badge visual (i.e., guidelines to ensure brand identity, possibly provided through a template).

Table 1a and 1b The critical information summary developed by the advisory committee for the pilot provincial micro-credential credit bank. This data standard is inspired by Beverley Oliver’s critical information summary (Oliver, 2019) and matches widely accepted data requirements for the description of a micro-credential in a digital badge. This proposed standard includes mandatory fields that all credentials should include, as well as optional ones. Given that several B.C. institutions have collaborated on it (the advisory committee is composed of representatives from RRU, VCC, KPU, UBCO, TRU, and BCCAT), this format is likely to become adopted as the B.C. standard. However, note that this proposed standard is currently under development and will likely evolve as it is implemented and tested.

| Core Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Institution | The institution or organization issuing the micro-credential. |

| Title | The title of the micro-credential. |

| Description | Description of the structure of the micro-credential and a summary of the content (key topics) that will be taught. |

| Delivery Mode | The method of delivery of a micro-credential, e.g., on site, online or a combination of both, and whether the micro-credential requires synchronous engagement or is asynchronous. |

| Learner Effort (estimated hours) | The commitment/ effort (volume of learning) required of learners. This estimate of hours should include:

|

| Pre-requisites (if applicable) | List any pre-requisites required before taking the micro-credential course or program. |

| Learning Outcomes | The knowledge, skills or competencies the learner will acquire upon completing a micro-credential, course, program, and credential assessment. |

| Assessment Method | The method and type of assessment (competency versus proficiency). |

| Credit/Other recognition | Credit towards other credit courses, credit towards vendor/ industry certifications, pathways or other recognition that can be given upon completion of a micro-credential. |

| Learner Pathways (stacking/laddering) | Any other micro-credentials that a micro-credential combines with that lead to an overall certification being awarded upon completion (stacking), or entry into a further credit course or program (laddering). |

| Quality Assurance Statement | The assurance that micro-credentials are developed and delivered in an educationally sound manner for learners. If there is a review cycle for the micro-credential, please specify. |

| Optional Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Department | The department within the institution that developed and delivers the micro-credential. |

| Level | Intended level of learning for micro-credential. (e.g., 1st year, 2nd year, 3rd year, 4th year, graduate level). |

| Endorsement | The assurance that micro-credentials meet an industry need and reflect skills sought by employers. For example, a statement of support from industry. |

| Instructor Qualifications | The academic and/or industry certification required to teach the micro-credential. |

| Further information | Additional comments might include a statement about depth of learning, learner resources, linkages to an industry competency framework, or regulatory body for the micro-credential as non-credit for non-specified credit. |

Suggested Resources

Open Digital Badges

A few primers on open digital badges.

Clements, K., West, R., & Hunsaker, E. (2020). Getting started with open badges and open microcredentials. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(1), 154–172. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i1.4529

ContactNorth. (2019). Ten facts about open digital badges. https://teachonline.ca/fr/node/101329

Alternative and digital credentials and badges

Don Presant, a Canadian authority on digital badges, maintains a blog that provides insightful commentaries on various aspects of digital badges. Notably, the blog features numerous figures and charts to help people understand and visualize important concepts, which are available for re-use and sharing under a Creative Commons licence.

The following edited book contains chapters on several aspects of micro-credentials and digital badges.

Ifenthaler, D., Bellin-Mularski, N., & Mah, D. K. (2016). Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials. Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-15425-1.pdf

An excellent report providing an overview of alternative digital credentials with recommendations.

ICDE Working Group. (2019). The present and future of alternative digital credentials (ADCs). The International Council for Open and Distance Education. https://www.icde.org/publication/the-present-and-future-of-alternative-digital-credentials/

A summary of principles for creating successful digital badging programs based on examples.

Smith, S. R. (2015). 10 lessons learned from an award-winning digital badging program. https://www.nextgenlearning.org/articles/10-lessons-learned-from-an-award-winning-digital-badging-program

Works Cited

Australian Government. (2022). National microcredentials framework. Department of Education, Skills and Employment. https://www.education.gov.au/higher-education-publications/resources/national-microcredentials-framework

Barabas, C., & Schmidt, P. (2016). Transforming chaos into clarity: The promises and challenges of digital credentialing. The Next American Economy’s Learning Series. Roosevelt Institute. https://luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/the-promises-and-challenges-of-digital-credentialing.pdf

Brown, J., & Kurzweil, M. (2017). The complex universe of alternative postsecondary credentials and pathways. American Academy of Arts & Sciences. http://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/academy/multimedia/pdfs/publications/researchpapersmonographs/CFUE_Alternative-Pathways/CFUE_Alternative-Pathways.pdf

Chukowry, V., Nanuck, G., & Sungkur, R. K. (2021). The future of continuous learning — Digital badge and microcredential system using blockchain. Global Transitions Proceedings, 2(2), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gltp.2021.08.026

Council of the European Union. (2022). Proposal for a council recommendation on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability – Adoption. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9237-2022-INIT/en/pdf

ContactNorth. (2016). Uber-U is already here. https://teachonline.ca/fr/node/85175

Crytzer, C., & Gance, S. (2018). A companion to the open badges specifications. IMS Global Learning Consortium. http://www.imsglobal.org/sites/default/files/Badges/OBv2p0Final/faq/index.html

Dimitrijević, S., Devedzić, V., Jovanović, J., & Milikić, N. (2016). Badging platforms: A scenario-based comparison of features and uses. In D. Ifenthaler, N. Bellin-Mularski, & D. K. Mah (Eds.), Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15425-1_8

Duklas, J., & Bridge, J. (2017). Creating a typology for alternative credentials to enhance student success, mobility, and transfer. Ontario Council on Articulation and Transfer (ONCAT). https://duklascornerstone.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Creating-a-typology-for-Alternative-Credentials.pdf

eCampusOntario. (2022). Quality assurance. In Micro-credential toolkit. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/microcredentialtoolkit/chapter/quality-assurance/

European Commission. (2021). A European approach to micro-credentials. https://education.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-01/micro-credentials%20brochure%20updated.pdf

Everhart, D., Derryberry, A., Knight, E., & Lee, S. (2016). The role of endorsement in open badges ecosystems. In D. Ifenthaler, N. Bellin-Mularski, & D. K. Mah, (Eds.), Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15425-1_12

Fedock, B., Kebritchi, M., Sanders, R., & Holland, A. (2016). Digital badges and micro-credentials: Digital age classroom practices, design strategies, and issues. In D. Ifenthaler, N. Bellin-Mularski, & D. K. Mah (Eds.), Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15425-1_15

Fong, J., Janzow, P., & Peck, K. (2016). Demographic shifts in educational demand and the rise of alternative credentials. Association for Professional, Continuing, & Online Education (UPCEA). https://upcea.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Demographic-Shifts-in-Educational-Demand-and-the-Rise-of-Alternative-Credentials.pdf

Gibson, D., Coleman, K., & Irving, L. (2016). Learning journeys in higher education: Designing digital pathways badges for learning, motivation and assessment. In D. Ifenthaler N. Bellin-Mularski, & D. K. Mah (Eds.), Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15425-1_7

Goger, A., & Laniyan, F. (2022). Whose learning counts? State actions to value skills from outside the classroom. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/whose-learning-counts-state-actions-to-value-skills-from-outside-the-classroom/

Hanafy, A. (2020). Features and affordances of micro-credential platforms in higher education. [Master’s thesis, Faculty of Management and Business.,Tampere University]. https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/124188/HanafyAhmed.pdf?sequence=2

Hickey, D. (2017). Endorsement 2.0: Taking open badges and e-credentials to the next level. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/2/endorsement-2-taking-open-badges-and-ecredentials-to-the-next-level

Hope, J. (2019). Give students ownership of credentials with blockchain technology. Enrollment Management Report, 23(2), 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/emt.30533

IMS Global Learning Consortium. (2022). Open badges: Elevate your learning with open badges. https://openbadges.org/

Kiiskilä, P., Hanafy, A., & Pirkkalainen, H. (2022). Features of micro-credential platforms in higher education. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022), 1, 81–91. https://www.scitepress.org/Papers/2022/110306/110306.pdf

Iafrate, M. (2017). Digital badges: What are they and how are they used? eLearning Industry. https://elearningindustry.com/guide-to-digital-badges-how-used

Institute-Wide Task Force on the Future of MIT Education. (2014). Final report. http://web.mit.edu/future-report/TaskForceFinal_July28.pdf

Iwata, J., Telloyan, J., Murphy, L., Wang, S., & Clayton, J. (2017). The use of a digital badge as an indicator and a motivator. International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies, Sydney, Australia. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED579293.pdf

Jones-Schenk, J. (2018). Alternative credentials for workforce development. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 49(10), 449–450. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180918-03

Johnson, S. (2017). In the era of microcredentials, institutions look to blockchain to verify learning. EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2017-10-31-in-the-era-of-microcredentials-institutions-look-to-blockchain-to-verify-learning

Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2020). Sharing achievement through digital credentials: Are universities ready for the transparency afforded by a digital world? In BM. Earman, P. Dawson, R. Ajjawi, J. Tai, & D. Boud, (Eds.), Re-imagining university assessment in a digital world. The enabling power of assessment (vol. 7). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41956-1_19

Lau, J. (2021). Digital badge metadata: A case study in quality assurance. Journal of Innovation in Polytechnic Education, 3(1), 27–36. https://jipe.ca/index.php/jipe/article/view/93

Leaser, D., Jona, K. & Gallagher, S. (2020). Connecting workplace learning and academic credentials via digital badges. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2020(189), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20396

Lumina Foundation. (2015). Connecting credentials: Making the case for reforming the U.S. credentialing system. https://www.luminafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/making-the-case.pdf

Milligan, S., & Kennedy, G. (2017). To what degree? Alternative micro-credentialing in a digital age. In R. James, S. French, & P. Kelly (Eds.), Visions for Australian Tertiary Education (pp. 41–54). Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne. https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2263137/MCSHE-Visions-for-Aust-Ter-Ed-web2.pdf#page=49

Moroder, K. (2014). Micro-credentials: Empowering lifelong learners. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/micro-credentials-empowering-lifelong-learners-krista-moroder

Oliver, B. (2019). Making micro-credentials work for learners, employers, and providers. Deakin University. https://dteach.deakin.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/103/2019/08/Making-micro-credentials-work-Oliver-Deakin-2019-full-report.pdf

Orr, D., Pupinis, M., & Kirdulyte, G. (2020). Towards a European approach to micro-credentials: A study of practices and commonalities in offering micro-credentials in European higher education. Network of Experts Working on the Social Dimensions of Education and Training (NSET). Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/en/resources/library/towards-a-european-approach-to-micro-credentials-a-study-of-practices-and-commonalities-in-offering-micro-credentials-in-european-higher-education/

Peer 2 Peer University, The Mozilla Foundation, & The MacArthur Foundation. (2011). An open badge system framework. https://wiki.mozilla.org/images/f/f3/OpenBadges_–_Working_Badge_Paper.pdf

Perkins, J., & Pryor, M. (2021). Digital badges: Pinning down employer challenges. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 12(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2021vol12no1art1027

Presant, D. (2023). Recipes for recognizing diverse badges and micro-credentials. [Blog post] Littoraly Don. https://donpresant.ca/open-badges/recipes-for-recognizing-diverse-badges-and-micro-credentials/

University at Buffalo. (n.d.) About micro-credentials. State University of New York. https://www.buffalo.edu/micro-credentials/about.html

Weaver, K. (2021). 6 common misconceptions about microcredentials and stackable credentialing. The Evolllution. https://evolllution.com/programming/credentials/6-common-misconceptions-about-microcredentials-and-stackable-credentialing/

West, R. E., Newby, T., Cheng, Z., Erickson, A., & Clements, K. (2020). Acknowledging all learning: Alternative, micro, and open credentials. In M. J. Bishop, E. Boling, J. Elen, & V. Svihla. (Eds.), Handbook of research in educational communications and technology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36119-8_27

Media Attributions

- Figure 1. This Venn diagram was adapted from Don Presant, who had himself adapted the image from Doug Belshaw which is under a CC BY licence.

- Figure 2. Examples of the image component of a digital badge, as issued by Capilano University’s school of continuing studies by Capilano University’s continuing studies, used with permission.

- Figure 3. Example of four digital badges that learners in the UBCO course Introduction to Digital Media can earn by Myron Campbell, UBCO, used with permission.