Chapter 9. Economic Transformation and Continuity, 1818–1860s

9.6 The Atlantic Colonies

As was the case with the Canadas, the Maritimes and Newfoundland also enjoyed an economic boom during the war years. After the war, they staggered and struggled until eventually entering an unparalleled period of prosperity. Expanding Atlantic markets would, overall, usher in an age of wind, wood, and water for the four colonies, even as steam-driven shipping was chugging across the ocean.

Wood

Various imperial tariff policies favoured wood products from British North America, most of which came from New Brunswick. Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland profited as well in the short run, but New Brunswick enjoyed two key advantages over the other colonies in this regard. First, it had better and bigger forests; second, it was criss-crossed by rivers that allowed logging camps to move deep into the interior in search of more trees.

While all four Atlantic colonies engaged in the lumber trade, they did so in different ways. Prince Edward Islanders depleted their own forests and then shipped out to New Brunswick in large numbers to work as seasonal labourers in the mainland logging camps. As well, Prince Edward Island manufactured some of the largest and most diverse ships associated with the forest industry. Newfoundland, too, produced large numbers of ships from its own forest supplies, but these were overwhelmingly in service of the fisheries industry and not meant to serve other exports. Newfoundland’s forest industry would grow on the Avalon Peninsula in particular in the 19th century but, like Nova Scotia, it faced limitations based on access. With few rivers that reached deep into either colony’s interior, the forests along the foreshore were denuded and the industry’s advance slowed until new investment and technology made inland tree stands more accessible.

In New Brunswick logging and sawmilling became year-round activities, spawning smaller milltowns along the Saint John River in particular. Demand for New Brunswick lumber was so great that the port towns (St. Andrews and Saint John especially, but also the settlements at the mouth of the Miramichi) began to produce ships designed specifically to carry squared timber. On arrival in British ports, these boats were either sold as shipping capacity or for their timber. With the exception of some brief market downturns (including, in 1821, a fire that burned across the middle of the province from the Miramichi through Fredericton) and some uncertainty from time to time about tariffs, the forest sector as a whole grew until 1860.

Imperial tariffs and other protectionist measures ensured privileged access to West Indian markets for Maritimers. During these years the links between the Atlantic colonies and British (and Spanish) Caribbean colonies strengthened. With New England frozen out of the British West Indies, the opportunity arose for Maritimers to stock them with fish, farm surpluses, and shipping capacity. Prince Edward Island benefited mainly from the market for farm products as none of the other three colonies had the same agricultural potential. Charlottetown in particular benefited from the need for more shipping capacity.

Wind and Water

Shipbuilding throughout the region was a leading sector, supported heavily, of course, by the timber industry. Saint John was home to the largest fleet and Charlottetown was second. Both ports built, registered, and chartered out their vessels. Some of these ships were bound for distant parts of the world such as the eastern Mediterranean and the west coast of South America. There, they would carry freight from one port to the next under the command of notoriously tough “bluenose” (Maritimer) skippers whose reputation for cutting costs was eclipsed only by that of their ship owners.

Wealth accumulated in Yarmouth, Halifax, Charlottetown, and Saint John, especially in the pockets of shipbuilders and owners. Their view of the world was not narrow and parochial: they were shipping in very distant waters and trafficking in exotic goods. More than that, their ships were themselves products for market. At mid-century, ships built in Charlottetown were being sold to buyers in Britain and the West Indies; more often than not island shipbuilders sold their output to Canadians and Newfoundlanders.[1]

Newfoundland began to tap more into the fisheries and seal colonies of Labrador as well and provided most of the fish that was traded abroad. Markets in Britain continued to be strong, although French competition returned to the Grand Banks from their base on St. Pierre and Miquelon. Tariff changes badly undermined Newfoundland cod exports to Spain (formerly its major marketplace) and forced a reorientation toward Portugal and the Italian states. Even Brazil, a Portuguese colony with Portuguese tastes, emerged in the early 19th century as a viable market for Newfoundland salt cod.

The internal workings of this industry changed in the first quarter of the century when the truck system arose. St. John’s merchants provided fishermen with credit to purchase nets and other essentials of the codfishing trade in exchange for their catch. The merchants bore the bulk of risk if the market failed, but the fishermen faced comparable risks if they borrowed too much and/or the catch was not big enough to settle accounts. On the face of it, this may seem to be a symbiotic relationship, one in which the success of one side depends ultimately on the success of the other. In practice, merchants and codfish buyers, or cullers, often took advantage of their knowledge of the marketplace to fix a lower price for the catch so that they could maximize profit. Fishermen were thus faced with two threats: the size of the catch might fall short and, even in good years, it might fetch a lower price than usual. Indebtedness and merchant financial worries became ongoing themes in the St. John’s and Newfoundland economies.[2]

Overall, the Atlantic colonies experienced the first half of the 19th century as years of growth and relative prosperity. Merchants in the main towns took on many of the aspects of the old Bristol merchants of early mercantilist days. They wanted to work in protected markets, they saw themselves benefiting from their colonial/imperial connection with the Crown, and they engaged in a kind of triangular trade involving the Caribbean plantation colonies. They also had a growing influence over colonial and imperial policy and came to form a powerful political force. These connections enabled the establishment, too, of financial institutions in the Maritimes, including the Bank of New Brunswick (founded in 1820 as the first chartered bank in British North America), the Bank of Nova Scotia (1832), and the Newfoundland Savings Bank (1834). These institutions facilitated the accumulation of colonial capital and its reinvestment in public and private enterprises.

Exercise: Documents — France in America, 1852

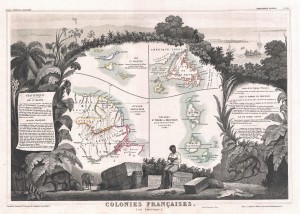

Victor Levasseur was part of a generation of cartographers whose work was meant to stimulate the mind in several ways. On the map in Figure 9.8 he shows what little is left of the French presence in the Americas, including St. Pierre and Miquelon, the little island chain south of Newfoundland that enables France to remain a presence in the Grand Banks and the Gulf of St. Lawrence to this day. Apart from the rather abashed looking tiger (embarrassed, perhaps, because he’s meant to be on a different map), what does Levasseur want you to take away from his document?

Key Points

- The Atlantic colonies enjoyed certain advantages in the timber trade and were able to parlay these into an expanded shipping and shipbuilding sector.

- New Brunswick was the leading timber exporter from the region, providing jobs for migrant seasonal workers from Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia.

- The interconnectedness of the Atlantic colonies with Britain, the West Indies, and farther afield were features of the colonial economies that distinguished them from the Canadas.

Attributions

Figure 9.6

New Brunswick map general by Qyd is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 9.7

Nova Scotia stamp by File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske) is in the public domain.

Figure 9.8

Colonies françaises (en Amérique) by AncelyBot is in the public domain.

Long descriptions

Figure 9.8 long description: A map framed by a scene of floral. Below the map, a man sits with his arms crossed and a dejected expression. Around him are animals and supplies. In the top corner, ships are sailing away. [Return to Figure 9.8]

Media Attributions

- Mr. Bell’s Forges on the St. Maurice River, near Trois-Rivières © 1844 by George Seton is licensed under a Public Domain license