Chapter 8. Rupert’s Land and the Northern Plains, 1690–1870

8.5 The Montrealers versus the HBC

Although the French were blocked from directly reclaiming territory on Hudson Bay, there was nothing to stop them from extending a string of trading posts in the Ungava Peninsula and the West. This strategy allowed them to block the supply of furs heading downriver to the bay.

Before the Conquest

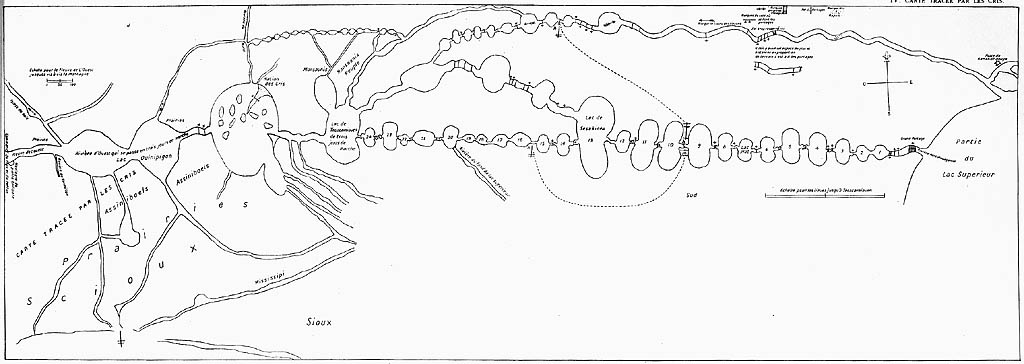

This chapter opens in 1727 with the western expeditions of Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de La Vérendrye. His mission represents, in part, a resumption of French efforts to find a northwest passage to the Pacific. His contacts around Lake Superior included Tacchigis, Ochagach, and Mateblanche, three Cree informants who provided La Vérendrye with intelligence and maps of the lake and river systems across the West. Complications arose when the Cree-French party encountered the Dakota Sioux at Lake of the Woods. There was long-standing enmity between the Dakota and the Cree, but also a recent alliance between the Dakota and the French in the Pays d’en Haut. The Dakota responded to this new French-Cree configuration as a betrayal on the part of the Europeans and slaughtered 19 in La Vérendrye’s group, including one of his sons.[1]

These French incursions and uncertain relations with some of their own Indigenous trading partners obliged the British to launch ambitious building projects on Hudson Bay. The most outstanding of these, though never completed, is Prince of Wales Fort at the mouth of the Churchill River. Begun in 1731, it was taken by the French in 1782 (during the American Revolution) without a shot being fired. The structure was partially demolished by the French before they handed it back to the British a year later. This was a minor setback for the HBC and the French were, in any event, out of the picture after the War of Independence (1775–1783). But it was part of a larger emerging competitive era, one which had its centre along the St. Lawrence.

The Rise of the Montreal Merchants

After the Conquest the main players in the fur trade out of Montreal were British-American merchants. Their trading houses absorbed elements of the old French operations, and the largest and most successful of the new conglomerate enterprises to emerge was the North West Company (NWC). Its leaders were mainly Scots who (like its founder, Simon McTavish) arrived in Canada after the Treaty of Paris (1763) and before the arrival of the Loyalists (1783). They had deftly avoided taking the American side in the War of Independence but that didn’t make them warm friends of the English regime. Nor did their Presbyterian creed stop them from marrying French-Canadian Catholic women. Between the Conquest and the end of the American Revolution they worked in competition with one another in the near-west and the Pays d’en Haut. The outcome of the Revolution and the Treaty of Paris (1783) encouraged them to band together; they were further obliged to develop new strategies for an area north of the 49th parallel after Jay’s Treaty (1794) reduced their ability to work in what was now the American northwest. Hard-headed businessmen with strong connections in New York, the Nor’Westers were a fluid and sometimes fractious set of partnerships that did their level best to subvert the HBC and evade the monopoly held in Asia by the British East India Company.

There may have been discontinuities in entrepreneurial leadership in Montreal, but the fieldwork remained structured much as before. The main corridor of trade was along the Canadian Shield via the site of Wendake (Huronia), into the northern Great Lakes, on to Michilimackinac, and then to the NWC’s main posts at, first, Grand Portage then at Fort William (now part of the city of Thunder Bay). Canadiens continued to play an important role in the actual trading and transshipment process, as did Iroquois, and Métis trip men and voyageurs. (Looking at a typical personnel list from any western expedition, it is difficult to imagine that it would be conducted in any language other than French.) The NWC pressed far into the interior of North America, seeking out furs. This expansionism was a direct challenge to their chief competitors, the HBC, which was just breaking out of its shoreline redoubts and heading upriver.

Another feature that distinguished the NWC is that it operated on a profit-sharing basis. A trader in the company could easily amass a good deal of wealth and had the motivation to do so. The wintering partners — the prominent NWC employees who spent the year in the West — were also part of the decision-making processes of the company. Sometimes also called hivernants, they would meet annually with the Montreal agents at Fort William where company-wide plans would be made in council. The family connections within the NWC — with McTavish at its centre — contributed a patriarchal structure to the decision making.

The consultative approach and shareholder system of the NWC was a stark contrast to the hierarchical business model of the HBC. Headquartered in London, the HBC was led by individuals with no direct experience of the fur trade who have been described, consequently, as “cautious, even timid.” Its employees were called “servants,” a title that reflects the deferential and status-conscious relationship they had with their “officers.” Indeed, many of the “servants” were working off seven-year indentures and could look forward at the end to a good letter of reference and a suit of clothes. “But,” as one scholar of the HBC says, “if the Hudson’s Bay Company was at times sluggish, it was never inert. Rigor mortis was not setting in. When it embarked in new directions the Company moved forward relentlessly, and all its advantages of organization and experience made it a formidable competitor.”[2] And when the HBC seemed most on the ropes — as it did in the first two decades of the 19th century — it bounced back.

Key Takeaways

- By the mid-18th century, French traders were making headway into the West.

- The post-Conquest fur trade saw the rise of British and British American merchants in Montreal.

- The two principal fur trade companies were organized very differently and each had specific strengths and weaknesses.

Long descriptions

Figure 8.8 long description: Map showing the routes that Hudson’s Bay Company explorers Henry Kelsey, Samuel Hearne, and Anthony Henday took while journeying across the interior of what is now known as Canada.

From 1690 to 1692, Henry Kelsey travelled southwest from York Factory at the mouth of the Hayes River, which feeds into southwest Hudson Bay. Kelsey followed the Hayes River southwest, past Lake Winnipeg in southern Manitoba and across Saskatchewan. Then, Kelsey looped back around to return to York Factory.

The map shows that Samuel Hearne took two journeys from Fort Prince of Wales, which is north of York Factory on the shore of Hudson Bay and right next to modern Churchill, Manitoba.

Hearne’s first journey in 1770 went west and north of Fort Prince of Wales and looped around Dubawnt Lake, which is on the modern border between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, a few hundred kilometres north of the point where Saskatchewan meets Manitoba, a few hundred kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. Then, Hearne travelled southeast to return to Fort Prince of Wales.

Hearne’s second journey was from 1770 to 1772. Hearne travelled northwest from Fort Prince of Wales across Manitoba and Saskatchewan to about 200 kilometres north of Lake Athabasca, which is on the border of Saskatchewan and Alberta. Then, he went north, past the eastern shore of Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories, past the Coppermine River, to a small bay near modern Kugluktuk, Nunavut, on the shore of the Arctic Ocean.

On the return journey, Hearne travelled south the way he came, then went southwest so that he cut across Great Slave Lake, then travelled east and eventually southeast to return to Fort Prince of Wales.

From 1754 to 1755, Anthony Henday travelled southwest from York Factory across modern Manitoba and Saskatchewan into Alberta. He reached Red Deer, Alberta, just east of the Rocky Mountains, then headed northeast along the North Saskatchewan River to return to York Factory.

Media Attributions

- Hudson’s Bay Company – Western Interior Exploration © 2010 by Alexrk2 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Map of Boundary Waters region © c. 1730 by Ochagach is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fort Prince of Wales © 1996 by Ansgar Walk is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- View of the two Company Forts on the level prairie at Pembina on the Red River, and surprise by the savages at nightfall of May 25, 1822 © 1822 by Peter Rindisbacher is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Arthur J. Ray, I Have Lived Here Since The World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People (Toronto: Lester Publishing, 1996), 79–81. ↵

- Daniel Francis, “Traders and Indians,” The Prairie West: Historical Readings, eds. R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1992), 69. ↵

A joint-stock fur trading company established in Montreal after the Conquest and led by British American and Scottish merchants. The principal competition to the HBC. The NWC’s agents were called North Westers or Nor’Westers.

Members of the fur trade whose principal task was to move furs, people, and materials across great distances. Some voyageurs were also traders. Also called trip men.

The prominent NWC employees who spent the year in the West. As part of the decision-making process, they would meet annually with the Montreal agents at Fort William, where company-wide plans would be made in council. Also called hivernants.