Chapter 5. Indigenous Canada in the Era of Contact

5.7 The Five Nations: War, Population, and Diplomacy

From the highest elevation, it might seem as though Indigenous peoples did little to resist European intrusion. Nothing could be further from the truth. Much of the history of Canada from 1600 to 1867 is marked by continual — and continually shifting — resistance mounted by the original inhabitants.

The League of the Great Law of Peace

No Indigenous nation was to manifest such a key role in the political history of northeastern North America in the 17th and 18th centuries as the Haudenosaunee Five Nations League. The Haudenosaunee allied with the Dutch and then the English, but contained them to their seaboard markets; they tore up Wendake (Huronia) by the roots and became dominant across an area that covered what are now nine American states and all of southwestern Ontario; they expanded their League while exacting tribute from intimidated Indigenous nations all around them. They became a military, economic, and political force with which to be reckoned.

Haudenosaunee traditions of warfare were never static. Their success arose from an ability to adapt tactics of both conflict and diplomacy in ways that their neighbours could not foresee. The Haudenosaunee were able to do this in part because their councils worked so effectively. Their processes demanded unanimity and they were able to achieve that because avoiding internal fractiousness was valued so highly. Political geography was another source of strength. The League’s territory included unimpeded access to the lower Great Lakes (Erie and Ontario), the St. Lawrence, the Lake Champlain corridor, and the Hudson River. They were a short voyage from New Amsterdam, as compared to the Wendat, who were hundreds of kilometres from the St. Lawrence. The Haudenosaunee could thus play a role as adversary or ally on short notice.

The French earned the enmity of the Haudenosaunee at Ticonderoga in 1610 but there were opportunities to win peace as well, although neither party was especially interested. In 1624 the League struck a peace with the Algonquin and Wendat so that they could turn their efforts against the Mahican (a.k.a. Mohican) whose lands lay along the Hudson River and who enjoyed primacy in the fur trade with the Dutch. Both the French and the Dutch were unhappy with this outcome, but it was a clear demonstration of the commercial goals of the League: they now could enter markets in both New Netherland and New England.

The Mourning Wars

The peace with the Wendat-Algonquin alliance lasted until 1636, although peace with the French was never assured. Champlain’s principal concern was to ensure the safe passage of the Wendat fur fleet in the spring. To that end he requested more troops from France and ordered the building of fortified settlements (including Trois-Rivières) along the St. Lawrence in 1634. The Haudenosaunee response was to build their own chain of fortified positions from which to better raid the fur brigades. For the next decade the League focused its efforts on harassing and capturing the Wendat-Algonquin fleets. This process intensified in the 1640s until 1647–1648 when the focus shifted to attacks on Wendat villages. Conflict between the Wendat and the Haudenosaunee had not before this time been so comprehensive. The Mourning Wars to that point had been retaliatory and retributory, but not a scorched-earth program. Taking the war into the heartland of the Wendat was a significant change in strategy, against which the Wendat failed badly.

The change in Haudenosaunee tactics reflected new circumstances. If the French were to be starved of furs to the point that they would seek peace and commerce with the League, then clearly their Wendat supply network had to be shattered. If the impact of smallpox and other exotic diseases on the Haudenosaunee was to be survived, then the practice of adopting captives would need to be more vigorously pursued. To that end, clearing out as many captives as could be harvested from a Wendat village and then torching it made sense. The loss of homes and food stores reduced the competition’s ability to serve the fur trade and made it impossible for captives to expect sanctuary at home if they were to run away. The Wendats’ trading partners would look elsewhere for maize and the Five Nations aimed to be the last major farming community in the region. Furs would head across Lake Ontario to the lands of the League, Haudenosaunee numbers would be replenished, and the Dutch and English would have no incentive to look beyond the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) trademarts and merchants.

The largest share of the Wendat exiles wound up in the League. The Tahontaenrat joined the Seneca, the Arendarhonon were absorbed by the Seneca as well but also by the Onondaga, and the Attignawantan were adopted by the Kanien’kehá:ka. These realignments were complex and they had interesting outcomes. Some of the Wendat took their Catholicism with them into the Five Nations and the Kanien’kehá:ka villages in particular; subsequently there was a significant out-migration to the area just south of Montreal where offshoot pro-French and pro-Catholic villages were established. As well, some of the former Wendat became prominent figures within Haudenosaunee political and military life.[1]

By 1660 the Haudenosaunee controlled the western lands that extended from the former Wendake (Huronia) east to the Ottawa River and south around Lake Michigan through the Ohio Valley. French accounts at the time suggest that the impacts of smallpox in the 1660s — on top of war losses in the 1640s and 1650s — combined with captive adoptions to create a situation in which there were more “foreigners” in Haudenosaunee villages than natives. The League’s purposes and vision did not change in the 17th and 18th centuries, but it is worth noting that by the 1660s the Five Nations was made up of very different personnel. It had, in effect, become an instrument for a more cosmopolitan Indigenous control of the region.

Historians on Video

Aspects of inter-cultural diplomacy are considered here by historian Peter Cook (University of Victoria). Here is a link to the transcript for the video titled What characterized the European approach to inter-cultural diplomacy? [PDF].

The Iroquois Wars

For the remainder of the century, the League pursued a complex plan to do two things: secure its southern frontiers against the rival Susquehannock nation and contain the French threat. The League established a truce with the French (1667) and with the northern and eastern Algonquin (1672). Turning their attention to the south, they secured that frontier by 1679 only to discover the French and French allies back in their western lands. This provoked the bloodiest confrontations to date between the Haudenosaunee and the French.

In 1680 the League returned to raiding Canadian settlements. The French replied with new infusions of troops and, in 1687, a path of devastation across Seneca territory. On July 26, 1689, the Haudenosaunee launched a reprisal attack on the village of Lachine, about 10 kilometres upriver from Montreal. Some 200 French and their allies were killed; the same number captured and marched off to League villages for torture and/or adoption. Lachine was razed.

The tide turned to the advantage of the French with the return of Count Frontenac, who found his forces facing both the Haudenosaunee and the English. Fortunately for Frontenac, the English were ineffectual as warriors and unreliable as allies to the Haudenosaunee. He was able to inflict a telling blow on League villages and food stores in the winter of 1694, an attack that, for once, caught the Haudenosaunee by surprise. The damage was severe and, following further French predations in 1696, the Haudenosaunee began to seek peace. The war with the French would, however, persist until 1701.

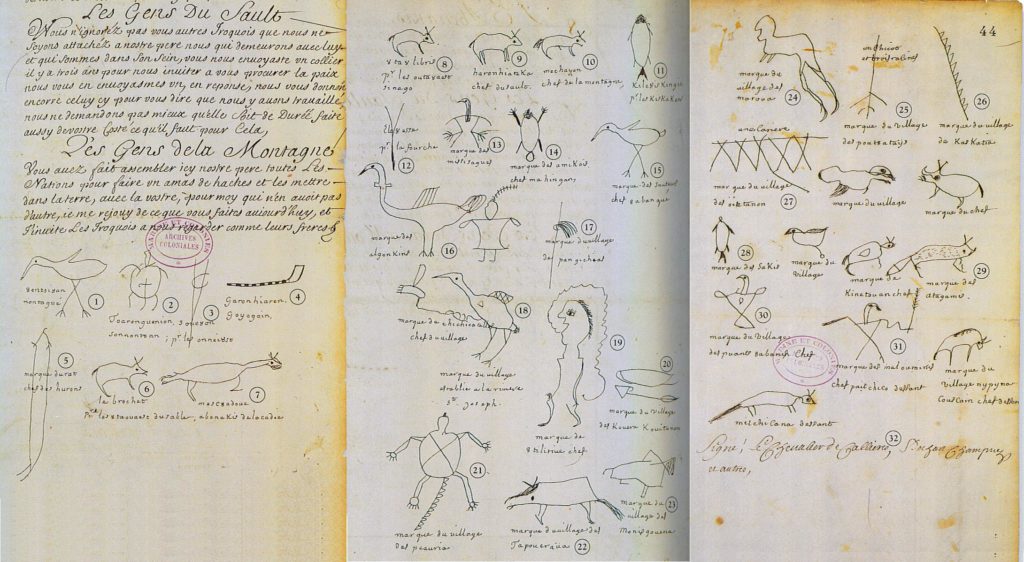

In the history of intercolonial conflict in North America the standard practice was to negotiate treaties between the European players and treat the Indigenous participants as subsidiaries. A treaty with the English was, as far as the French were concerned, binding on the Indigenous allies of the English. Frontenac broke with that practice in 1697: he regarded the Treaty of Ryswick of that year as having no purchase on the Haudenosaunee and he pressed for a separate treaty. This he won at the Great Peace of 1701, also known as the Great Peace of Montreal.

From the Haudenosaunee perspective, the 1701 Great Peace reflected a need to reconcile conflicts within the League. It was reckoned that two-thirds of the Kanien’kehá:ka population had gone over to the French side while the remainder continued their staunch loyalty to the British. By winning a peace with the French and their allies, the Haudenosaunee were in a position to whipsaw the English against the French for trade and military support. This was confirmed when the Haudensaunee struck a separate treaty with the English at Albany in the same year. Having given the French permission to build a trading post at Detroit (Fort Pontchartrain), they secured commitments from the English to keep the French out of that very region.

It was this strategy of ostensible neutrality coupled with the Europeans’ fear that the Five Nations could tip either way that the Haudenosaunee used to protect their territory. Signing two treaties with the Europeans underlined, too, the Five Nations’ self-awareness as an autonomous political entity. One obvious goal of the Haudenosaunee — one that other Indigenous nations did not pursue with as much success or alacrity — was containing the newcomer settlements. So long as the Haudenosaunee were a buffer state between the French and the English, the Europeans were happy with their continued presence. The Five Nations knew this and would find ways to exploit their position in the 18th century.

At the same time, by 1712 it was clear that the League was not the force it had been. Its warrior numbers had been reduced by half, the Kanien’kehá:ka had lost as much as two-thirds of their population to villages nearer to Canada, and the League was divided over whether the English were a threat or a source of support against the French.[2]

Key Takeaways

- The Haudenosaunee League was positioned and equipped to be a resilient military force and commercial hub.

- Destroying the French-Wendat-Algonquin fur trade alliance was part of a larger Haudenosaunee agenda in the late 17th century.

- Having destroyed Wendake (Huronia), the Five Nations launched a military campaign that won them a huge territory and an advantageous position as a buffer state between the English and the French.

Long descriptions

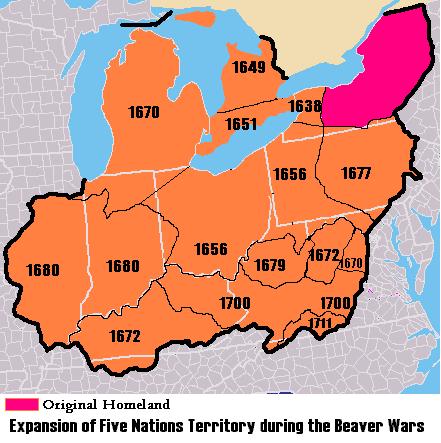

Figure 5.11 long description: Map showing the expansion of Five Nations territory during the Beaver Wars. The original homeland of the Five Nations was in what is now eastern New York state and bordered on the southern and eastern shores of Lake Ontario. During the Beaver Wars (1609–1701), the Five Nations expanded their territory along the following timeline:

- 1638: Five Nations territory expands to include more of southern New York state, westward along the southern shore of Lake Ontario and to the eastern shore of Lake Erie.

- 1649: The Five Nations claim a swath of land in southern Ontario west of Lake Ontario and east of Lake Huron, including the modern-day cities of Toronto and Mississauga.

- 1651: The Five Nations expand south to the southernmost strip of southern Ontario along the northern shore of Lake Erie.

- 1656: Territory expands to include southwest New York state, western Pennsylvania, most of Ohio, northern West Virginia, and a strip of northern Maryland.

- 1670: The Five Nations gain control of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, part of northern Indiana, a slice of northwest Ohio, and a small area in eastern Virginia.

- 1672: The Five Nations claim another region farther to the west in Virginia, as well as western Kentucky and a strip of northern Tennessee.

- 1677: The Five Nations expand to eastern Pennsylvania, strips of southeastern New York state, and another slice of northern Maryland.

- 1679: Territory expands to include central West Virginia.

- 1680: The Five Nations gain control of a slice of southwestern Ohio, the rest of Indiana, and eastern Illinois.

- 1700: The Five Nations expand to eastern Kentucky and a large swath of western Virginia.

- 1711: The Five Nations gain control of another pocket of southern Virginia.

Video Attributions

- Dr. Peter Cook Question 3 – European approach to inter-cultural diplomacy. © 2015 by TRU Open Learning is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Media Attributions

- Five Nations Expansion, 1638–1711 © 2011 by Codex Sinaiticus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- La Grande paix de Montréal © 1701 by Louis-Hector de Callière is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bruce G. Trigger, Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s ‘Heroic Age’ Reconsidered (Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1985): 259–280. ↵

- Richard Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier, 1701–1754 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1983), 70–71. ↵

A treaty struck between New France and 40 Indigenous nations. The Great Peace drew to an end the long-running war between Canada and the Haudenosaunee Five Nations and what had become known in some circles as the Beaver Wars. Also known as the Great Peace of Montreal.