Chapter 8. Rupert’s Land and the Northern Plains, 1690–1870

8.3 Intrusions during the 17th Century

Until the 1690s, Europeans made only small forays into the lands of the Innu (Montagnais and Naskapi), the Cree, the Dënesųlįné, and the Inuit. Existing networks of traders and middlemen (such as the Wendat and the Innu) made it unnecessary for the French to extend their reach farther north. Another factor that limited the French intrusion in the North was the persistent belief that a body of water bisected the continent. Given how deeply the St. Lawrence penetrates North America and how much farther still the Great Lakes basin can be followed inland, this makes some sense. What massive river must somewhere feed into the Great Lakes and thus into the St. Lawrence? Would it just be a matter of finding the right portage? Somewhere between the Missouri and the Assiniboine, it was reckoned, there was a river that was to the west what the St. Lawrence was to the east. That hope that a waterway to the Pacific and then to China existed was difficult to shake and it served to delay French movement northward from the colony of Canada.

The British were similarly impelled to hunt out a northwest passage. They, however, came at the problem from the North, via Hudson Strait and then Hudson Bay.[1] The first documented attempt to do so was that of Henry Hudson in 1610–1611. It ended badly for Hudson: his crew mutinied and cast Hudson, his son, and his remaining loyal crew adrift. Efforts to find a northwest passage would continue for more than two centuries but, in the meantime, there were renewed fur trading opportunities in the North.

It is likely that the Cree first encountered Europeans before Hudson’s ill-fated expedition. A single Cree male, without being urged to do so, offered Hudson and his crew deer and beaver pelts and then withdrew them when goods offered in exchange were not to his liking. This story is taken by some scholars as evidence that the Cree trader was familiar with European goods and their value relative to Indigenous products.[2] For the next 40 years, Cree furs would find their way into the hands of merchants on the St. Lawrence via Anishinaabe and Algonquin middlemen and the Wendat trademart. The destruction of the Wendat Confederacy closed that outlet, although their first-tier middlemen were still mostly in place.

The prospect of direct trade was attractive to the Cree. Price markups that were added as goods passed south along the way to New France meant that the original suppliers on Hudson Bay received far less than their commercial allies closer to the St. Lawrence. And the goods the Cree received in return were costly and of poorer quality. With that in mind, Cree trappers attempted from the 1670s on (if not earlier) to draw the attention of the French to their rich stock of fur animals in the North. The French, however, were in the midst of their compact colony experiment and were concerned that opening posts on “the frozen sea” would undermine what little progress had been made in the development of the St. Lawrence Valley.

Two French fur traders (and brothers-in-law) — Pierre Esprit-Radisson (1636–1710) and Médard des Grosilliers (1618–1696) — held a different perspective. They tried to demonstrate the value of this new market intelligence by heading straight to James Bay. They returned with a daunting number of high-quality pelts. Rather than receive a hero’s welcome, however, they were disciplined for ignoring the governor’s strictures against trading farther north. Subsequently Radisson and Grosilliers took their knowledge to Bostonian merchants and then to the English. They found an interested party in Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619–1682), an entrepreneurially astute German-born cousin of King Charles II. In 1670 a monopolistic charter modelled on the East India Company was granted to “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay,” known more economically as the Hudson’s Bay Company (or simply, the HBC). The territory involved was a massive drainage basin, which the Crown named Rupert’s Land.

Into the Bay

Looked at straight on, the map of North America shows Hudson Bay as a gut that sags into the middle of Canada. For navigators, however, it is a vast inland sea with a huge coastline, a gulf that opens through the wide channel of Hudson Strait into the North Atlantic. In nautical miles, the distance between Bristol and York Factory is almost exactly the same as between La Rochelle and Montreal. There was hope, too, that one of the river systems that empties into the western bay might lead to a Pacific opening. On this score the British (and the French) were disappointed. Once in the bay, however, European fur traders had direct access to the principal Indigenous trappers and traders with whom the French had been dealing second-hand down south. This cheered them up.

In 1668, two years before the formation of the HBC, the English established a fort in an area on James Bay (known to the Cree as Waskaganish) and named it Rupert House (a.k.a. Charles Fort). The HBC followed up with two other James Bay posts: Moose Fort (a.k.a. Moose Factory) in 1673 and Fort Albany in 1677. The French launched a response almost immediately. In 1672, in a case of foreshadowing that was ignored by the English, a Jesuit priest (Charles Albanel) and a small party of French from Canada crossed Innu territory from Tadoussac via the Saguenay and reached Rupert House. The intent of this mission was evidently diplomatic but it was inconclusive: no one was at home at the HBC fort, so the Jesuit left a note and his party returned to Canada.

A more robust response came in 1686 when Chevalier de Troyes, a French captain recently arrived in Canada, led an overland expedition to James Bay. The attack on Moose Fort was successful and de Troyes (along with the d’Iberville brothers) went on to capture Rupert House and then Fort Albany. This hat-trick campaign took place when France and England were officially at peace, another case where colonial agendas superseded imperial interests. The English returned in 1688 but failed to win back the forts; they were more successful in 1696. The Treaty of Ryswick the following year settled very little and war on the bay resumed in five years’ time. It was not until the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) that French claims on both James Bay and Hudson Bay were formally relinquished.

More than two generations of intermittent conflict and what the Cree experienced as useful competition between the Europeans around the bay finally came to a close. The 18th century would see the French presence expand in the West and the HBC would follow suit. Thanks to wars in the eastern woodlands and in Europe, as well as skirmishes in the bay itself, the cultural and other consequences of commerce between Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties in the West and North were at this stage not yet extensive. Things would quickly change in this regard.

Exercise: Documents — Beaver Fever

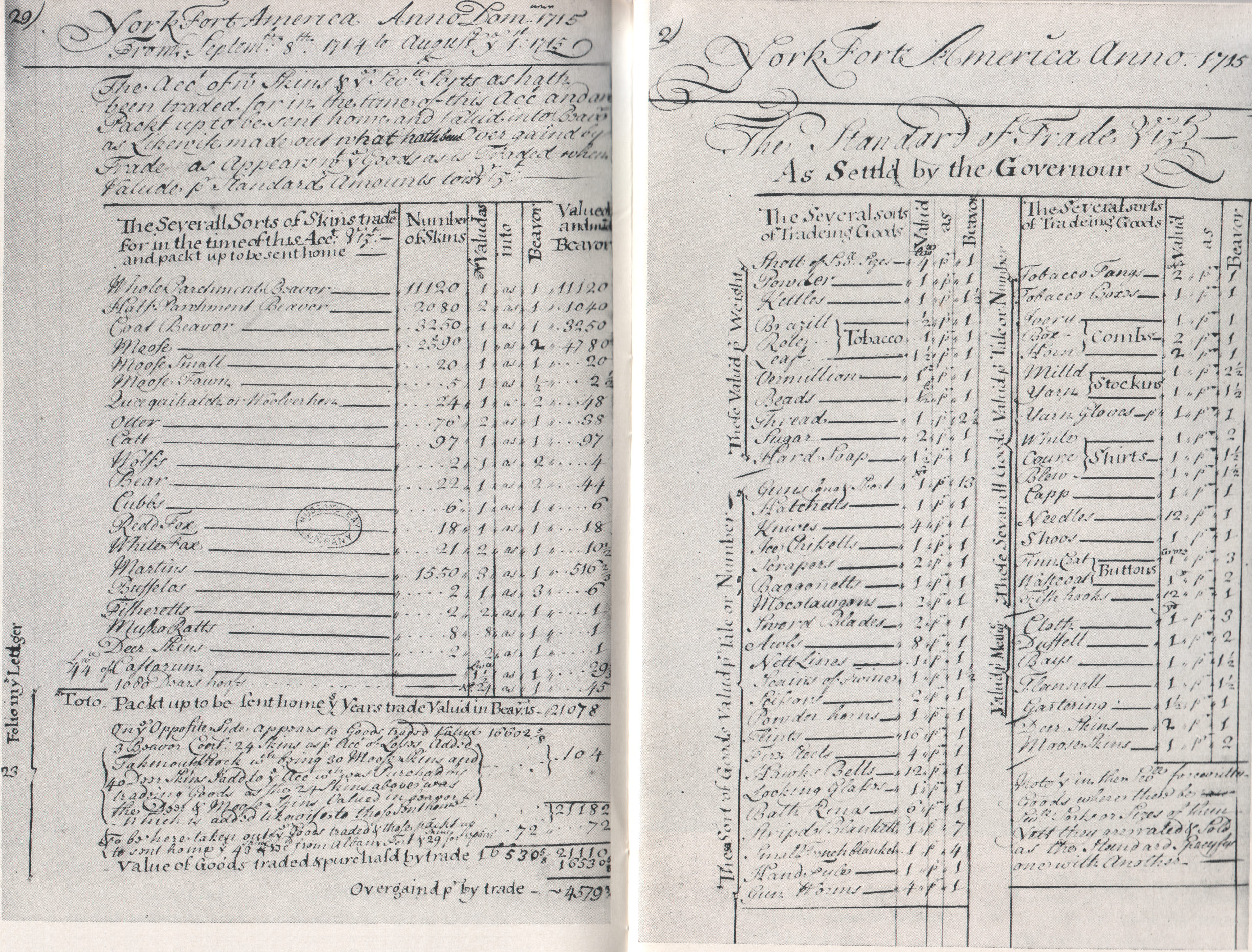

The fur trade in the interior of North America is about beaver. In countless museum exhibits, films, re-enactments, and so on, it’s about beaver. The crest of the HBC proudly incorporates a beaver. Truth be told, the HBC (and the North West Company) were pretty open-minded when it came to other kinds of pelts. Certainly beaver pelts were at the heart of the industry and some of the confusion arises from what might be called the “exchange rate” of the fur trade: the “made beaver.” This standard was based on an adult male beaver taken in winter, when the fur would be at its thickest.

All commodities traded in or out of Rupert’s Land were reckoned in terms of their “made beaver” value. Look at this record of furs traded at Fort York (York Factory) in 1714–1715 (see Figure 8.6). The left-hand ledger shows the quantity of furs purchased at the fort and their relative value in “made beaver.” The right-hand ledger shows the value of European goods reckoned per “made beaver.” For example, while red fox pelts were accepted at par with “made beaver,” white foxes were only half as valuable. And one “made beaver” could purchase two “scrapers.” Just looking at the columns (and not the very-difficult-to-read material at the bottom), how many different animal remains were being traded at Fort York and what was the most valuable? Looking at the right-hand column, what does 21,078 “made beaver” buy?

Key Takeaways

- French forays into the Hudson Bay drainage before the late 1600s were largely unnecessary and less promising than explorations into the West.

- British interest in the region resulted in the creation of a chartered monopoly and the erection of forts along the edge of Hudson Bay.

- The HBC monopoly was not a deterrent to French incursions and competition, all of which worked to the advantage of Cree and Innu traders.

Long descriptions

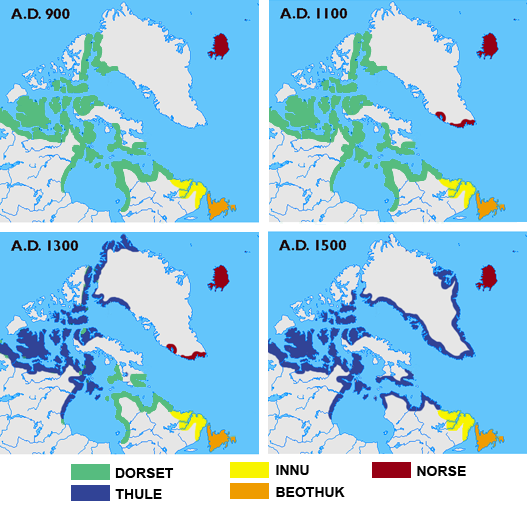

Figure 8.4 long description: Four maps of the Arctic showing the territorial ranges of five cultures — the Dorset, Thule, Norse, Innu, and Beothuk — between 900 and 1500 CE. In order:

- 900 CE: The Dorset occupy the coasts and islands of northwestern Quebec, Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories, as well as a small portion of the coast of Greenland. The Norse occupy Iceland. The Innu occupy northeastern Quebec and Labrador. The Beothuk occupy Newfoundland.

- 1100 CE: The Norse now occupy the southern coast of Greenland, plus Iceland.

- 1300 CE: The Thule have taken over much of Dorset territory on the coasts and islands of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, plus a larger portion of the northern coast of Greenland. The Dorset still occupy the northwestern coast of Quebec, a few isolated areas of islands in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, parts of the southern coast of Baffin Island, and one sliver of coast near the north of Manitoba.

- 1500 CE: The Thule occupy virtually all of the territory that used to belong to the Dorset, with minor variations. The Thule are the sole occupants of Greenland, holding about three-quarters of its coast. The Dorset are completely gone from the Arctic. The Norse hold Iceland; the Innu hold northeastern Quebec and Labrador; and the Beothuk hold Newfoundland.

Figure 8.6 long description: A photocopy of a trade ledger showing two tables. The first table is a list of skins traded from September 8, 1714, to August 1, 1715, by the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fork York (York Factory) in Ontario. The second table shows the value of European goods in units of “made beaver,” which was the “exchange rate” of the fur trade.

| Skin | Quantity | Skin to Made Beaver Ratio | Value of Quantity in Made Beaver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole parchment beaver | 11,120 | 1 to 1 | 11,120 |

| Half parchment beaver | 2080 | 2 to 1 | 1040 |

| Coat beaver | 3250 | 1 to 1 | 3250 |

| Moose | 2590 | 1 to 2 | 4780 |

| Moose, small | 20 | 1 to 1 | 20 |

| Moose, fawn | 5 | 1 to ½ | 2½ |

| Quickhatch or wolverine | 24 | 1 to 2 | 48 |

| Otter | 76 | 2 to 1 | 38 |

| Catt[3] | 97 | 1 to 1 | 97 |

| Wolves | 2 | 1 to 2 | 4 |

| Bear | 22 | 1 to 2 | 44 |

| Cubs | 6 | 1 to 1 | 6 |

| Red fox | 18 | 1 to 1 | 18 |

| White fox | 21 | 2 to 1 | 10.5 |

| Martens | 1550 | 3 to 1 | 516⅔ |

| Buffalo | 2 | 1 to 3 | 6 |

| Fishers | 2 | 2 to 1 | 1 |

| Muskrats | 8 | 8 to 1 | 1 |

| Deer skins | 2 | 2 to 1 | 1 |

| Castoreum | 44 | 1½ to 1 | 29⅓ |

| Deer hooves | 1080 | 24 to 1 | 45 |

| Total | N/A | N/A | 21,078 |

| Trading Good | Good to Made Beaver Ratio |

|---|---|

| Shot of [illegible] sizes | 4 to 1 |

| Powder | 1 to 1 |

| Kettles | 1 to 1½ |

| Tobacco, Brazil | 1 to 1 |

| Tobacco, rolls | 1 to 1 |

| Tobacco, leaf | 1½ to 1 |

| Vermilion | 1 to 1 |

| Beads | ½ to 1 |

| Thread | 1 to 2½ |

| Sugar | 2 to 1 |

| Hand soap | 1½ to 1 |

| Guns [illegible] | 1 to 13 |

| Hatchets | 1 to 1 |

| Knives | 4 to 1 |

| Ice chisels | 1 to 1 |

| Scrapers | 2 to 1 |

| Bayonets | 1 to 1 |

| Mocotaugons | 2 to 1 |

| Sword blades | 2 to 1 |

| Awls | 8 to 1 |

| Net lines | 1 to 1 |

| Skeins of twine | 1 to 1½ |

| Scissors | 2 to 1 |

| Powder horns | 1 to 1 |

| Flints | 16 to 1 |

| Fire steels | 4 to 1 |

| Hawk bells | 12 to 1 |

| Looking glass | 1 to 1 |

| Bath rings | 6 to 1 |

| Striped blanket | 1 to 7 |

| Small French blanket | 1 to 4 |

| Hand file | 1 to 1 |

| Gun worms | 4 to 1 |

| Tobacco tongs | 2 to 1 |

| Tobacco boxes | 1 to 1 |

| Combs, ivory | 1 to 1 |

| Combs, box | 2 to 1 |

| Combs, horn | 2 to 1 |

| Stockings, milled | 1 to 2½ |

| Stockings, yarn | 1 to 1½ |

| Yarn gloves | 1 to 1 |

| Shirts, white | 1 to 2 |

| Shirts, [illegible] | 1 to 1½ |

| Shirts, blue | 1 to 1½ |

| Cap | 1 to 1 |

| Needles | 12 to 1 |

| Shoes | 1 to 1 |

| Buttons, tin coat | 1 to 3 |

| Buttons, waistcoat | 1 to 2 |

| Fish hooks | 12 to 1 |

| Cloth | 1 to 3 |

| Duffle | 1 to 2 |

| Bays | 1 to 1½ |

| Flannel | 1 to 1½ |

| Gartering | 1½ to 1 |

| Deer skins | 2 to 1 |

| Moose skins | 1 to 2 |

Media Attributions

- Arctic cultures, 900 to 1500 CE © 2006 by Masae adapted by Premeditated Chaos is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Rupert’s Land © Themightyquill is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- List of skins traded at York © 1715 by Hudson’s Bay Company is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Historically, the possessive is used, i.e., Hudson’s Bay. In the 20th century the possessive gradually fell out of use for the place, but not for the company. Thus: Hudson Bay and Hudson’s Bay Company. ↵

- Olive Patricia Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, 3rd edition (Don Mills: OUP, 2002), 73. ↵

- Possibly “bobcat.” ↵

The water route connecting the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean via the Arctic Ocean.

In 1670, a monopolistic charter modelled on the East India Company that was granted to “The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.” Also known as the HBC.

According to the HBC’s charter of 1670, all the lands draining into Hudson Bay. Includes northwestern Quebec, northern Ontario, most of Manitoba, some of central Saskatchewan and Alberta, as well as southeastern Nunavut.