Chapter 6. Intercolonial Rivalries, Imperial Ambitions, and the Conquest

6.9 Colonial Conflict to 1713

Any odds-maker looking at the prospects for French victory against the English in the colonial wars from the 1620s on would have to call it a long shot. The colonies all depended on naval support, and England’s Royal Navy was larger than that of France or Spain by 1660. The population in the English colonies grew at a much faster rate so that by 1760 they were 20 times larger than New France. What settlement existed in New France was stretched out and difficult to defend, certainly compared to the more urban and compact colonies to the south. Many of the young Canadiens who might act as a colonial regiment were off trading for furs in the spring and summer — precisely when they were needed most at home for defence. Nevertheless, the French record against the British in North America is remarkably good.

This is, however, a two-dimensional view in a three-dimensional world. Indigenous nations were in an almost constant state of resistance against European intruders in these years. Whether it was the Beaver Wars or the Wabanaki Wars or battles too small to acquire a name, Indigenous communities in northeastern North America were struggling to adjust to a world in which trade relationships were changing, epidemics were devastating their numbers, and aggressive neighbours (European or Indigenous) were impinging on their lands. Some of these conflicts become apparent in the historical record only when they folded neatly into intercolonial or inter-imperial wars. While it is true that the French, to take one side, sought out and nurtured alliances with Indigenous partners in their struggle to contain the British and their colonists, it is also true that Indigenous nations had their own agendas and welcomed the French into their crusades, regardless of the European context.

The End of the Iroquois Wars

As described in Chapter 5, the Haudenosaunee launched attacks against Canada in the late 1680s, one of which was a spectacular assault on Lachine. The governor, Count Frontenac, responded with raids against the settlements of the Iroquois and those of their English allies. The French forces by this time had adopted guerrilla tactics favoured by the Algonquin and the nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The raids were lightning-fast and terrifying. By destabilizing the English colonial frontier, Frontenac hoped to sever the connection between his two enemies, and he was eventually successful. This was a bloody, no-holds-barred campaign in which civilians and children were not spared.

The English colonists responded with a naval assault that captured the Acadian capital of Port-Royal and then a failed attempt to take Quebec. It was in this latter conflict that Massachusetts’ future governor, Sir William Phips, demanded Frontenac’s surrender, to which the latter offered to reply from the “mouths of my cannon and muskets.” Phips’s forces found Quebec a challenging opponent, and they became anxious about the coming winter and freeze-up on the river. They retreated with nothing to show for their efforts. Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville captained several naval sorties into Hudson Bay in an effort to root out the English HBC, but the outcomes of these battles were continually undone the next season.

The European powers were too preoccupied with their own conflicts to wade in on either side, which is much of the reason that there was no decisive result. France and England were consumed with sectarian wars involving, among others, the Protestant alliance between England and the Netherlands against their common Catholic foe, France. The War of the League of Augsburg lasted nine years in Europe and the outcomes in North America were decided at the treaty table in 1697 (in the Treaty of Ryswick), not on the battlefield. This was a theme that was repeated throughout the 18th century when colonial conflicts would be fought mostly by locals and settled abroad by the mother countries after the fact.

A key outcome of the War of the League of Augsburg was the appearance of sharp divisions within the Haudenosaunee League. For the Kanien’kehá:ka, located farthest east, the British position at Fort Albany (formerly Fort Orange) was regarded as part of a deepening pact. They were not about to desert this asset and commitment. That was not the case, however, for the rest of the Iroquois. The League had played a key role in renewing hostilities with the French at Lachine, and they didn’t care one way or the other about agreements made at Ryswick: they had their own agenda. The French felt similarly that Ryswick addressed European issues and that Canadian security against the Iroquois had to be resolved in battle. It took another three years for the two sides to become sufficiently exhausted by war to seek a separate peace. The agreement signed by the Onyota’a:ka (Oneida), the Seneca, the Onondaga (whose main village had been levelled), and the Gayogohó:no (Cayuga), on the one side, and the French, on the other, was the Great Peace of 1701. War between the two parties had been almost continuous since 1608 and now, with the exception of the Kanien’kehá:ka (which was a very big exception indeed), Canada could relax a little. For the League, however, it meant that their relationship with the English was compromised. How badly compromised would soon be revealed.

The War of the Spanish Succession

Within a year the peace in Europe was shattered. England and France were once again at war. In North America, conflict followed quickly. In this relatively short period of time, however, much had changed. Frontenac had completed building a chain of forts deep into the Mississippi Valley and his plans for a more integrated New France were gaining ground. The forts were established both for trade and to consolidate military alliances with Indigenous nations. The Great Peace gave the French some room to manoeuvre in the Ohio Valley and build a presence and forge a role with the Council of Three Fires. Moving the principal western post from Michilimackinac to Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit (Detroit) created opportunities for closer connections with the Potawatomi and the Miami (another Algonquian-speaking group, one that had been displaced by the Haudenosaunee during the Beaver Wars and was at this time returning to the Ohio Valley). The fort attracted conflict almost immediately, especially between the Council (which regarded the Miami as intruders in their zone of influence) and various Iroquois who were now able to participate in regional trade under the protection of the Great Peace. Diplomacy on the part of the French was essential to taking advantage of the western forces that could be mustered in another war with English colonists, but this endeavour was neither smooth nor particularly successful.

As well, years of war had hardened New France. Canadien soldiers emerged as ferocious guerrilla fighters who could more than hold their own against the Haudenosaunee and take the battle to the enemy’s doorstep with impunity. The administrative structure of New France was also militaristic. Frontenac had put his stamp on the whole of the colony in this respect and was able to deploy resources without difficulty. This simplified the business of building alliances with Indigenous nations. While the individual British colonies had to work out their own alliances piecemeal, New France could speak with one voice when it came to the Wabanaki Confederacy or the peoples of the Pays d'en Haut.

These were important differences. While the French were establishing outposts throughout Indigenous territory and extending their commercial and military influence, they were not claiming land for their own exclusive use. New Englanders, New Yorkers, and other English colonists, however, were much more aggressive in this respect, enlarging their frontiers inch by inch in smaller conflicts with native populations. It was for this reason that the Wabanaki Confederacy aligned so strongly with the French. The presence of priests in their communities gradually and successfully introduced Catholicism, giving the Wabanaki another reason to despise their Protestant English neighbours.

The War of the Spanish Succession (also known as Queen Anne’s War) began officially in 1702. The first five years were dominated by failed New England attempts to retake Port Royal (which had been handed back to France at Ryswick) and highly effective assaults by the French-Wabanaki alliance on New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The attack on Deerfield, Massachusetts, a village of hardly 300 people, saw more than a hundred prisoners being marched off to Caughnawaga (a.k.a. Kahnawà:ke and Kahnawake), a mostly Iroquois mission village near Montreal where many were adopted into their captors’ population. New England responded with raids on Acadia, which had roughly the same impact. It wasn’t until 1710 that a British force was brought into the struggle and was able to capture Port Royal (renamed Annapolis Royal). In 1711 Britain once again attempted to take Canada. Seven regiments along with 1500 colonials sailed into the St. Lawrence. Ten of their ships were sunk and the expedition failed.

The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 ended the war and settled the disposition of territorial prizes, mostly to the disadvantage of New France. On balance, the French were right to claim victory on the battlefield, but the French colonies did badly at the bargaining table. The treaty resulted in the relinquishing of French claims to mainland Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Newfoundland, including the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon. France retained Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) and Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island); the Acadians remained a question mark for the British throughout their new possession, now called Nova Scotia. This outcome was, of course, very bad news for the Wabanaki Confederacy, as it was now sandwiched between two regions of British colonization.

Key Takeaways

- New France was able to withstand repeated attacks from the British and the British colonies by forging alliances with Indigenous neighbours and by adapting their guerrilla warfare techniques.

- Indigenous interest in the fur trade and regional security resulted in alliances with colonial settlements and imperial powers.

- Whatever the outcome of war on the colonial battlefields, the final outcomes were settled at the treaty table in Europe.

- The Treaty of Utrecht reconfigured the colonial map in North America.

Long descriptions

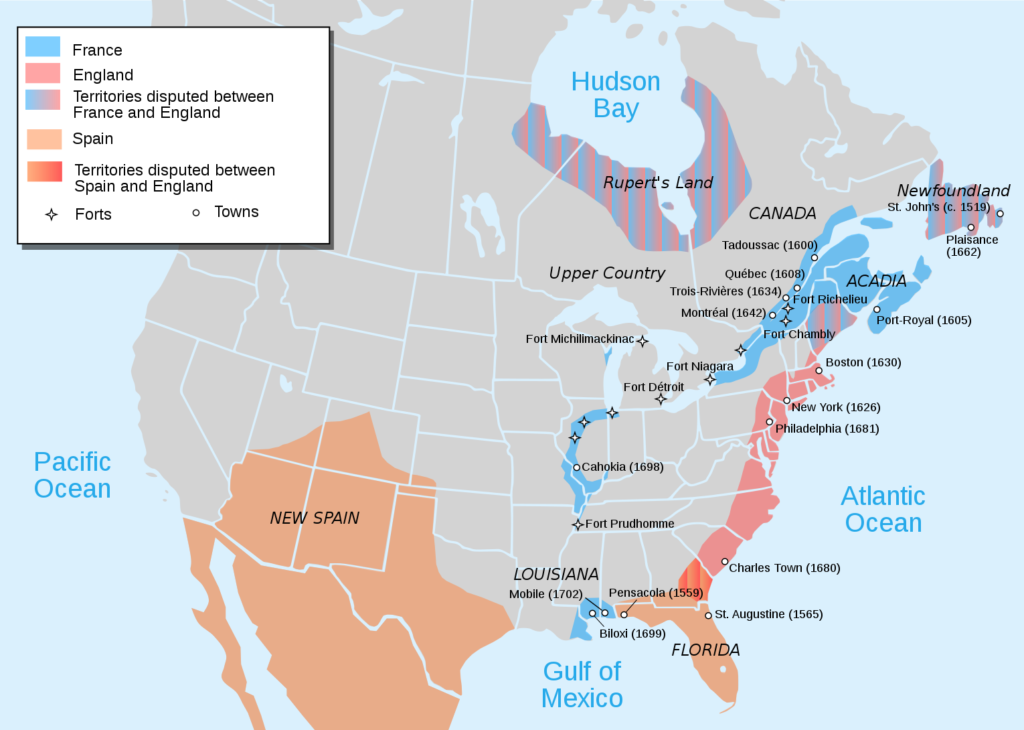

Figure 6.8 long description: Map showing the territory claimed by Spain, England, and France, respectively, in 1702, right before Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713).

Spain controlled much of southern North America. This includes Mexico, Arizona, New Mexico, southeast Utah, much of western Colorado, a sliver of southwest Kansas, the Oklahoma panhandle, and western Texas, as well as Florida and a sliver of southeast Alabama and southwest Georgia.

England controlled nearly the entire east coast of the United States, from New Hampshire to South Carolina, ranging from just the coastal areas of the states in that region to larger swaths.

Spain and England quarrelled over who owned southeast Georgia.

France controlled portions of the south coast of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. It also controlled a streak going from northeast to southwest Illinois and eastern Missouri. France also occupied a sliver of Wisconsin that protrudes into Lake Michigan.

Most notably, France controlled a large area around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, including Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and the land in Quebec, Ontario, and New York around the St. Lawrence River. France also controlled northern Maine and the south shore of Lake Ontario in New York.

France and England disputed over southern Maine, the island of Newfoundland, and the land around Hudson Bay from northeastern Manitoba to northern Ontario to western Quebec.

Media Attributions

- North America in 1702 © 2010 by Magicpiano is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

A form of warfare distinguished by the lack of structure and organization typical of formal warfare. Characterized by ambushes, small units, and lightning raids, guerrilla warfare aims to demoralize and wear down a larger opponent that lacks the same speed and mobility.

Treaty from 1697 that terminated the War of the League of Augsburg and restored the status quo in North America from before the war.

A treaty struck between New France and 40 Indigenous nations. The Great Peace drew to an end the long-running war between Canada and the Haudenosaunee Five Nations and what had become known in some circles as the Beaver Wars. Also known as the Great Peace of Montreal.

A part of New France containing much of what is now Ontario, the whole of the Great Lakes, and notionally all the lands draining into them. Extended as far as the Upper Mississippi and the Missouri. Translates roughly into the “upper country.”

Treaty from 1713 that ended the War of the Spanish Succession. French claims on territory in Newfoundland, on Hudson Bay, and Acadia (Nova Scotia) were ceded to Britain, except for Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean.