Chapter 13. The Farthest West

13.8 The Island Colony

The loss of the Oregon Territory was a blow to the HBC but not necessarily to British ambitions in the region. The former remained resilient while the latter remained modest. The HBC had experimented with commercial diversification for years, expanding its network across the Pacific. The arrival and employment of Kanakas throughout the Pacific Northwest reflected the diversity of marketplaces into which the HBC reached.[1] It was clearly about much more than beaver and sea otter pelts.

One noteworthy (if Pyrrhic) victory in this regard was the Puget Sound Agricultural Company (PSAC), a barely-at-arm’s-length subsidiary of the HBC created in 1840 and centred at Port Nisqually (Tacoma) in what is now Washington State. The PSAC had several goals, including the establishment of a loyal British settler community in the face of American intrusion into the Oregon Territory, improved self-sufficiency in terms of food supply to the northern forts, and an experiment in settler colonialism. Like Lord Selkirk’s project at Red River, the HBC conceived PSAC in part as an attractive retreat for retired employees and their families. The Oregon Treaty ended the PSAC experiment but its objectives were to continue to the north, on Vancouver Island.

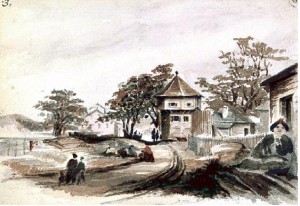

Fort Victoria

Fort Camosun opened in 1843 and its name changed to Fort Victoria in 1846 in honour of the new queen. This was the first settlement of Europeans on the island since the Spanish abandoned Fort San Miguel at Yuquot in 1795. The HBC feared the Lekwungen (Songhees) and their neighbours, and there was little confidence that even a simple landfall would succeed. The priorities of the Lekwungen, however, included incorporating the British operations into their own. Some 300 to 400 Indigenous men took on the task of building the fort and the band provided all the lumber required for the task. Historian John Lutz argues that this apparent welcome was a kind of appropriation by the Lekwungen. In their society, housebuilding was a communal activity and it was one that signified, importantly, community ownership of the structure. Building the HBC fort, therefore, signified a Lekwungen stake in the affair.[2]

Relations between Indigenous peoples and the HBC entered a new phase after the construction of Fort Victoria. There were confrontations, some of which involved what Barry Gough describes as gunboat diplomacy.[3] Often the source of irritation was cultural differences. Many northwest coast peoples were horticulturists, though not farmers in a sense that newcomers instantly recognized. Europeans often witnessed them clearing the land with fire in order to create meadows, so the newcomers knew that land management was underway. For example, the West Coast camas bulb was an important source of food for Indigenous peoples and a trade good in its own right. But the camas bulb is one of many local foodstuffs that did not gain admittance to the Columbian Exchange: Europeans never really came to like its flavour. If they had, they might have done more to protect camas patches against the newly introduced cattle and pigs. Of course, a cleared patch of land is more attractive to a farming settler than a stand of towering Douglas firs: the gardens of northwest coast peoples were much sought after and were quickly seized by newcomers. Indigenous peoples, for their part, regarded anything on four legs as potential game, which was predictably bad news for livestock and for the newcomer-Native relationship, but good news for the banquet table.

The Colony of Vancouver Island

In 1849 the British extended to the HBC a 10-year lease on the proprietary colony of Vancouver Island, conditional on its settlement by newcomers. The new colonial paradigm was difficult for the HBC to accept. Settlers and furs and Natives were not viewed as a good mix, not by the HBC’s officers and not by the Indigenous populations. The Whitman Massacre of 1847 was still at the forefront of everyone’s minds. Aware of the possibility of foot-dragging on the settlement front, the Colonial Office dispatched Richard Blanshard (1817-1894) to serve as governor.

Blanshard was probably the only non-Indigenous person on the whole island who did not work for the HBC and, as he was soon to discover, the company did not work for him. In the space of 10 years the HBC had experienced an enormous shift, one that had seen the end of their Oregon and Californian enterprises along with the loss of Fort Vancouver and the York Factory Express route. The company’s local operations were headed by Chief Factor James Douglas but he now had to take orders from London and the Colonial Office. What’s more, Westminster instructed the HBC to bring in significant numbers of non-company personnel to become settlers; it was likely that the newcomers’ relationship with the Indigenous nations would be different from — which is to say, at odds with — that of the fur trading company. It is hardly any wonder, then, that Governor Blanshard found himself isolated and frustrated. If that weren’t enough, his timing was spectacularly bad.

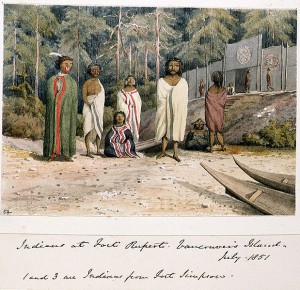

Gold fever had erupted in California in 1848. By 1849 eager prospectors were streaming into San Francisco, some of them from Fort Victoria. At around the same time, the HBC decided to pursue more aggressively a coal mining possibility at the northern tip of the island. The company established Fort Rupert in the late 1830s at Beaver Harbour, a Kwagu’ł (Kwakiutl) village site called ʦax̱is. This was the company’s only fort that existed for purposes other than trading furs or growing food. Kwagu’ł men and women dug out the coal or gathered it along the beach and traded it to the HBC, thus expanding their range of commerce. By 1848, however, the company was preparing to lurch into the industrial age by bringing out a party of experienced Scottish coal miners. The experiment was a disaster. It outraged the Kwagu’ł and they made common cause with the miners against the HBC. In 1850 the Scots were either chained up in the fort’s bastion or preparing to make a run for it.

As this drama unfolded, another came into view. Two British sailors who hoped to hitch a ride to San Francisco and the riches of the Californian El Dorado jumped ship in Victoria and then, mistakenly, onto a vessel headed north. Arriving in a troubled Fort Rupert, they fled into the forest where they were murdered by parties unknown. Blanshard’s response was to sail a gunboat into Beaver Harbour and shell the nearby Nahwitti village as he pursued the killers. Fed up with his low wages, poor living conditions, and lack of real authority, he returned to Fort Victoria and submitted his resignation — which London was happy to accept, given his rampage at Nahwitti.

Douglas was now governor of the colony with orders to take material steps to settle the island with colonists loyal to the Crown. Recruitment efforts were modest, not least because the prospect of new settlers was viewed as inconsistent with diplomatic and commercial relations with the Indigenous peoples. There was a veneer of theory applied to this hesitance. In the early 1850s the colonial theories of Edward Gibbon Wakefield (1769-1862) — one of members of Lord Durham’s expedition to the Canadas — gained wider support. Wakefield’s views resonated nicely with the HBC establishment on the island: he thought it was better to reproduce in colonies the kind of social relations found in Britain’s hierarchical culture than to open up the land to homesteading and an influx of commoners. As a result, land prices were set at a level that was seen as attractively exclusive. Only a certain class of settler would, in effect, be admitted. In the face of free land policies south of the border, the Wakefieldian approach on Vancouver Island failed.[4] The number of land sales was acceptable, but the number of settlers was never great. What’s more, those HBC servants who might have had it in mind to achieve some independence on the land were kept in their social class by this expense, thus preserving a pool of labourers. Finally, the hierarchical society that Wakefield (and James Douglas) had in mind for Vancouver Island led to the creation of the “squirearchy,” an HBC-connected elite that occupied all the key appointed positions in the colony, including the whole of the judiciary.

The Crown had been reluctant to hand authority to Douglas for fear that he was in a conflict of interest. Indeed he was. Douglas was mistrustful of settlers and defensive of aboriginal rights as he saw them. He negotiated a suite of 14 agreements, known as the Douglas treaties. These were initiated under Blanshard’s watch and Douglas continued pulling treaties together through the decade. Each aimed at obtaining lands deemed suitable for settlement or HBC enterprise. The treaties preserved First Nations village sites intact and allowed for one-time compensation payments. Some First Nations actively sought treaties from the HBC but Douglas had a limited budget at his disposal and no interest in obtaining territory where there was no immediate likelihood of use by newcomers. These treaties stand as the only ones negotiated west of the Rockies until very recently.

West Coast Industrialization

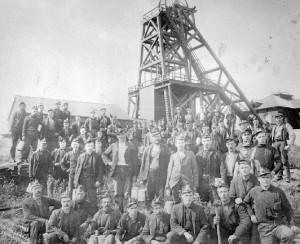

The experiment in coal mining at Fort Rupert was a disappointment. The Kwagu’ł claimed ownership of the coal and obstructed the use of Scottish miners. The immigrant coal miners — who constitute the first group of foreigners delivered to the region for the purpose of settling or doing a particular job since Meares’s Chinese shipbuilders — objected to the way the work was organized, the conditions under which they were mining, and the whole culture of HBC fort life. The operation was wound down and a promising coal seam to the south was explored. Many of the miners subsequently wound up at Fort Nanaimo in the Sneneymuxw territory. Douglas signed a treaty with the Sneneymuxw in 1854 and in that year a shipload of English miners from Staffordshire arrived, along with their families. In total, the HBC sponsored the immigration of 435 individuals for the coal mining projects until 1855, 85 of which were children. These immigrants and those who followed them were exceptional in the history of Canadian population: they were working-class people drawn from isolated communities in Britain and their voyage west by sea took them around the southern tip of South America, to Hawaii, and then to the island colony. There was effectively no going back. In a colony where the “squirearchy” looked down its nose at agricultural labour, the status of the miners and their families was lower still.

The success of the coal mining enterprise was slow in coming. It was helped along, indirectly, by the Russians. The island’s proximity to Russian waters pulled the colony briefly into the orbit of the Crimean War (1854). A joint British-French assault on the Russian Pacific port of Petropavlovsk ended in disaster and the injured troops were evacuated to Fort Victoria. These events advanced the case for a Royal Navy base and one was established next to Victoria Harbour at Esquimalt in 1865. Naval officers subsequently developed close links with the coal mining operations around Nanaimo. As more steam-powered naval vessels arrived in the Pacific, the coal resources became more important; as the coal mines grew in strategic significance so too did the value of having a naval base nearby to protect them.

The gold rush on the mainland also helped the coal mines, as did the growing demand for household fuel in San Francisco and Victoria. In the early 1860s the HBC sold its interest in Nanaimo to a London-based company and the chartered company gave way to industrial capitalism. A former HBC employee, Robert Dunsmuir, found his own coal seam nearby in 1869 and began building an industrial empire and dynasty. Two years earlier the first Chinese mine workers arrived at Nanaimo, the beginning of a migration wave that would continue through the rest of the century. By the third quarter of the century Nanaimo and environs was one of the largest industrial nodes in British North America.

Christianizers

Missionary activity on the coast also began at the mid-century. William Duncan (1832-1918), a controversial and mercurial representative of the Church of England’s Church Missionary Society (CMS), arrived in 1857. He set up shop at Fort Simpson (also known as Lax Kw’alaams and Port Simpson, near current-day Prince Rupert) and subsequently relocated hundreds of Ts’msyan to a mission town of his creation: Metlakatla. “Duncan shaped a landscaped place,” at Metlakatla, according to one source, “with rows of identical, single-family dwellings. Each house had a small garden, glass windows, sash curtains, and was fitted with beds and clocks. The church and other public offices were Metlakatla’s largest and most imposing buildings.” The overall effect was that of a European community built around ideals of individualism, the nuclear family, and “slum clearance.”[5] Duncan aimed to change people by changing their environment first: notably his idea of appropriate housing, individualism, and patrilineal inheritance was a direct critique of local culture. Duncan took the view that good Christians came out of nuclear households with a strong patriarchal legal and belief system in place.[6] While cultural change among Indigenous people on the northwest coast had been occurring throughout the fur trade period, the arrival of missionaries like Duncan and his successor at Fort Simpson, the Methodist Thomas Crosby (1840-1914), witnessed the first concerted efforts by newcomers to transform Indigenous societies and beliefs on the West Coast.

The 1850s were marked, then, by a rising colonial administrative presence, the beginnings of cultural assaults, some increase in newcomer settlement, and further decline in the fur economy counterbalanced somewhat by increased diversification of HBC activities. Where Fort Rupert failed as a mining operation, Fort Nanaimo succeeded and new arrivals from British coal fields continued the process of industrial resource extraction. The decade also witnessed diversification of Indigenous economies, a greater number of Indigenous peoples trading their labour for goods, and significant instances of resistance to newcomer transgressions. All of this change would be very suddenly eclipsed by events in 1858.

Key Points

- The HBC established the Colony of Vancouver’s Island to replace Fort Vancouver and as a starting point for a joint HBC-Colonial Office settlement project.

- The presence of newcomers in their midst both enriched and endangered Indigenous peoples of the island and the central coast.

- Agriculture, harvesting coal, and other economic activities were undertaken to further trade with the foreigners and also to increase their dependence.

- Settlement in the colony took two forms: a patriarchal and pastoral echo of the relationship between British gentry and commoners, and an industrial, proletarian townscape.

- The industrial revolution arrived on Vancouver Island in the late 1840s and spread in the 1850s to the mid- and south island.

- Missionary efforts on the West Coast accelerated in the 1840s, richly funded in the first instance by the CMS.

Attributions

Figure 13.24

Fort Victoria watercolour by Bonas is in the public domain.

Figure 13.25

HMS Sutlej gun deck LAC by Rcbutcher is in the public domain.

Figure 13.26

Blanshard by Fishhead64 is in the public domain.

Figure 13.27

Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Indians at Fort Rupert, Vancouver’s Island, July 1851 (Canada) by KAVEBEAR is in the public domain.

Figure 13.28

Nanaimo Mine Explosion-1 by Drovosekk is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

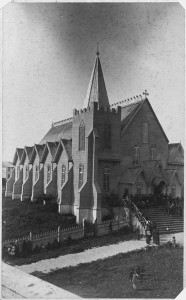

Figure 13.29

William Duncan’s church, Metlakahtla, B.C. is in the public domain. This image is available from the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the ARC Identifier (National Archives Identifier) 297830.

- Tom Koppel, Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: Whitecap Books, 1995). ↵

- John Lutz, Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 70-71. ↵

- Barry M. Gough, Gunboat Frontier: British Maritime Authority and Northwest Coast Indians, 1856-1890 (Vancouver; UBC Press, 1984). ↵

- Tina Loo, Making Law, Order and Authority in British Columbia, 1821-1871 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 38. ↵

- Daniel Clayton, "Geographies of the Lower Skeena," in Home Truths: Highlights from BC History, eds. Richard Mackie and Graeme Wynn (Madeira Park: Harbour, 2012), 114-115. ↵

- Clarence Bolt, Thomas Crosby and the Tsimshian: Small Shoes for Feet Too Large (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992), 24. ↵