Chapter 11. Politics to 1860

11.16 Summary

Politics between 1818 and 1860 was very much like the economy. It was fluid and evolving while remaining deeply unchanged. Some Tory values, which included a deep dislike for republicanism, survived and percolated out to influence groups that were their dedicated foes. Papineau, for example, embraced loyalty to the Crown for most of his career and Lafontaine did so as well. The Tories themselves were not a fixed point: they changed from being the landed gentry in most colonies into a commercial class with heavy investments in infrastructure, distilleries, and breweries. They required the support of a professional class of lawyers and notaries who would, in turn, challenge the various Family Compacts around British North America.

The commercial and capitalist orientation of the Haligonian and Montreal elites became obsessions of this new liberal professional class as well. There is much to be learned about the nature of British North American society through a close study of the life of someone like John A. Macdonald, and nothing is as revealing as his pilgrimage from the periphery of Toryism as a francophobic Scottish Presbyterian lawyer in deepest Loyalist Kingston to the leadership of a dualist Conservative Party. A contrary tide took many of the most staunchly Tory elements in Montreal into the arms of republicanism in the late 1840s as, feeling abandoned by Britain, they nearly turned their back on the monarchy to seek a future exclusively in North America. One expects positions to change; the speed with which British North American political leaders dramatically adjusted their thinking and their priorities in these years makes the 20th century look static by contrast.

At least one other feature of this period deserves careful thought, because it is so often dismissed in a cavalier way. The Constitutional Act of 1791 may have had structural weaknesses that provoked and hardened opposition and demands for reform, but it lasted for 50 years. There wasn’t a single constitution in France that lasted that long before the 20th century. The Act of Union had a lifespan of 26 years. As historians we must ask what features of the Constitutional Act created conflict; we must also ask what features made it so durable under the circumstances.

These are questions to keep in mind as we consider the steps taken to achieve Confederation in 1867. What values lay behind the movement to bring together the colonies and what external forces played a role? What was happening and what did people believe was happening? What was the level of public engagement in this process? How did this take place in the utter absence of any involvement of Indigenous representation? Who were the disenfranchised of this period and how was their status reflected in the constitutional arrangements worked out in Charlottetown, Quebec City, and London?

Key Terms

Act of Union, 1841: The constitutional arrangement for the Canadas that replaced the Constitutional Act of 1791. Its main features were union of Lower and Upper Canada, creating one colony and one colonial government and an identical number of assembly seats for both partner colonies, with an eye to subsuming the French-Catholic community. The Province of Canada retained some regional divisions, and the old colonies perpetuated their separate identities as Canada East and Canada West.

Chartists: A movement for political reform in Britain during the 1830s; the supporters of the People’s Charter of 1838 — the Chartists — called for universal adult male suffrage, equitable constituencies, and other innovations, which would radically broaden British democracy.

Clear Grits: Reformers in Canada West who coalesced in 1850 behind a platform of universal adult male suffrage and attacks on privilege. Principally rural at first, it became more urban under the leadership of George Brown in the late 1850s. Its founders called for men who were morally incorruptible, “all sand and no dirt, clear grit all the way through.” The Clear Grits joined with the Reformers and subsequently became the Liberal Party.

Durham Report: The Report on the Affairs of British North America of 1839 was the product of Lord Durham’s investigation in 1838 into the causes of the crisis in Canadian politics.

established church: The single official institutionalized religion of a state or nation. In the case of France prior to the Revolution and New France prior to the Conquest, it was unquestionably the Catholic Church; in Britain and its colonies, it was the Anglican Church (or Church of England). Post-Conquest attempts to impose the Anglican Church on the Canadas as the established church failed.

guardian: In the case of Indigenous relations with the state, the Crown (effectively, the Government of Canada) acts as the caretaker of Indigenous lands and property in a capacity roughly comparable to that of a parent or guardian of a child. The process of creating this role began in 1839 with the Crown Lands Protection Act and was fleshed out after Confederation in the Indian Act of 1876.

humanitarianism: A movement and philosophy that enjoyed particular support in the first half of the 19th century. Humanists argued that every individual shared a common moral significance. It was, as a movement, opposed to slavery and advanced the cause of working-class rights. It also sparked a renewed interest in the condition of Indigenous peoples.

Hunter Lodges, Hunter Patriots: Lodges formed by 1837-38 rebels who sought sanctuary in the United States and proposed to launch attacks on the Province of Canada from across the border. Members of the Lodges were called Hunter Patriots.

Master and Servants Acts: A suite of laws dating from the 18th and 19th centuries that sought to regulate the relationships between employers and employees. Formed the bedrock of industrial relations law, although these Acts were heavily weighted to the advantage of employers and were designed to minimize the ability of labour organizations to interfere with the ability of business to act freely.

Montgomery’s Tavern: The site of the main confrontation between Radical-Reform rebels and colonial troops in Upper Canada in 1837.

Ninety-Two Resolutions: A list of demands put forward by Louis-Joseph Papineau and the Parti patriote in 1834 calling for extensive political reforms. Britain replied with the Ten Resolutions.

patrilineal: Lines of inheritance that descend through fathers to their children. Compare with matrilineal.

representation by population: A series of demands assembled by the Parti patriote under the leadership of Louis-Joseph Papineau in 1834.

republicanism: In British North America, a pro-democracy movement; anti-monarchical and modelled on the American republic and, to a lesser degree, the French republic.

responsible government: The principle that the executive council should be subject to the approval of the elected assembly and that, should it lose that approval, the executive council can be dismissed by the elected assembly. Under the Constitutional Act of 1791, the executive council was entirely appointed; under the Act of Union of 1840-41, the executive was in practice elected.

status: In the context of laws affecting Indigenous peoples from the mid-19th century on, the notion that some Indigenous people have official standing as Indigenous peoples and that the criteria behind this “status” is determined not by the Indigenous community but by the state.

telegraph: Communications technology that permits the transmission of a message electronically across significant distances. Characterized in the Victorian era by the use of lengths of telegraph wire, which ran on posts parallel to the railroads and thus kept stations in touch with one another.

Ten Resolutions: In response to the Parti patriote’s Ninety-Two Resolutions, the British Colonial Secretary, John Russell, submitted to Parliament a counter-proposal that ignored all of the Patriotes’ demands.

ultramontanism, ultramontanists: In British North America, Catholic clergy who took their institutional, spiritual, and political leadership from the Vatican.

Short Answer Exercises

- How did the Constitutional Act create oligarchical regimes?

- Who were the main critics of the Constitutional Act?

- Who were the leading figures in government and who were their critics?

- What solutions were proposed to the constitutional crisis in the 1820s and 1830s?

- What was the role of media in the mid-19th century?

- What were the objectives of the rebellions of 1837-38? How did Lord Durham understand these events?

- What were the goals of the Act of Union?

- What is “responsible government” in the context of 19th century politics?

- How did the forces of Toryism respond to the new constitutional conditions in the Act of Union years?

- What was the role of political parties in these years?

- How did working people, Indigenous peoples, and women figure into the political culture?

- What weaknesses were built into the Act of Union? What strengths?

Suggested Readings

- Cadigan, Sean T. “Paternalism and Politics: Sir Francis Bond Head, the Orange Order, and the Election of 1836.” Canadian Historical Review 92, no.1 (March 2011): 319-347.

- Greer, Allan. “Rebels and Prisoners: The Canadian Insurrections of 1837-38.” Acadiensis 14, no.1 (1984): 137-145.

- Greer, Allan. “From Folklore to Revolution: Charivaris and the Lower Canadian Rebellion of 1837.” Social History 15, issue 1 (January 1990): 25-43.

- Morgan, Cecilia. “’When Bad Men Conspire, Good Men Must Unite!’: Gender and Political Discourses in Upper Canada, 1820s-1830s.” In Gendered Pasts: Historical Essays in Femininity and Masculinity in Canada. Edited by Forestell, Nancy M., Kathryn M. McPherson, and Cecilia Louise Morgan, 12-28. Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 2003.

- Radforth, Ian. “Political Demonstrations and Spectacles during the Rebellion Losses Controversy in Upper Canada.” Canadian Historical Review 92, no.1 (March 2011): 1-41.

Attributions

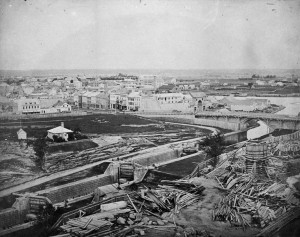

Figure 11.16

Canal locks and Major’s Hill 1860 by Skeezix1000 is in the public domain.