Chapter 13. The Farthest West

13.9 The Gold Colony

Tranquille Creek pours into Kamloops Lake about 15 kilometres west of the HBC’s fort at the confluence of the two branches of the Thompson River. In the 1850s the Tk’emlúps people retrieved small quantities of gold from the creek and canyon and offered it in trade at Fort Kamloops. After amassing a considerable nest egg’s worth of minerals, the HBC traders became concerned that it might be nothing more than fool’s gold. James Douglas (who still played the role of leading trader on the mainland, as well as governor of Vancouver Island) quietly shipped out a sample to the mint at San Francisco for assaying. Word of the gold’s quality leaked out of the mint within hours of testing and the Fraser River gold rush was underway.

The Rush

The earliest phase of the Fraser gold rush included production of gold by Indigenous labour on a commodity-trade basis from 1856, if not earlier. The Nlaka’pamux in particular were industriously pulling gold ore from their river (which appeared on European maps as the Thompson beginning in the 19th century) in 1857 and were already fighting off Americans from the old Oregon Territory who had followed rumours of gold in the north. What happened in 1858, however, was of a different order of magnitude.

No other event in Canadian history so transformed a region and its people in such a short period of time. This story goes well beyond the 15,000 to 20,000 who sailed out of San Francisco to Victoria and the mainland in the summer of 1858. It is much more than the administrative and political changes entailed in the creation of the new Crown colony of British Columbia, the appointment of Douglas as its first governor, and the establishment of a capital at New Westminster. And it goes well beyond the thousands of newcomers who added to the existing non-Indigenous community as permanent residents.

The gold rush had severe environmental implications. Miners compromised salmon runs by flushing sand and silt into the spawning grounds as they tried to extract gold. They stripped hillsides of trees needed for mine posts, flumes, and houses; erosion followed. Extensive and sterile rock piles throughout the interior even now indicate where Chinese miners painstakingly piled river rocks after they had been carefully washed clean of gold dust.

There was, too, bloodshed in the Okanagan by American prospectors accustomed to killing off Indigenous people who got in their way, and that was followed by warfare in the Fraser Canyon as the Nlaka’pamux resisted foreign incursions.[1] The Fraser Canyon War was instigated by French miners who allegedly raped a Nlaka’pamux girl; their bodies were subsequently found downstream, decapitated. Claims at the time of huge mortalities must be taken with a grain of salt, but it is clear that skirmishes did take place, lives were lost, and the event could have easily cost Britain its new colony.

Douglas could not afford to wait for the Colonial Office to send instructions. He raced a gunboat to the mouth of the Fraser and imposed a licensing system on the incoming miners, a way of demonstrating British sovereignty and gathering revenues. Shortly thereafter the Colonial Office made Douglas governor of the new colony of British Columbia and insisted he cut his ties with the HBC. A new capital was established at New Westminster (at the Kwantlen village of Sxwoyimelth) and Fort Langley enjoyed a brief renaissance. A corps of Royal Engineers were introduced and acted as a kind of police force throughout the colony. Steamboats were soon plying the river to the height of navigation at Yale.

The Cariboo

The gold frontier rapidly spread north, one arm diverting east to reincorporate Tranquille Canyon and the main part headed into the Cariboo Plateau. Barkerville emerged in these years as the largest centre of population in both British Columbia and Vancouver Island with numbers in excess of 10,000 (Victoria held barely 6,000 in 1863). The boomtowns of Likely, Richfield, and Quesnel also appeared at this time, many of them heavily populated by Chinese miners from Taishan.

Few of the gold prospectors made the fortunes they’d hope to. The cost of supplies was grotesquely inflated, the miners chased off much of the game they might have lived off, and Indigenous communities tended to give them a wide berth. Survival became the chief preoccupation of many prospectors. Shopkeepers and saloon keepers, however, did quite well, though never well enough to pay for the infrastructure needed to sustain the gold rush. The Cariboo Wagon Road was the major government initiative of the day, connecting Lillooet and Lytton (Camchin) with Barkerville. Way stations appeared (the many Mile Houses of the interior) and the whole was policed by a regiment of British Royal Engineers, called the Sappers.

The Fraser and Cariboo gold rushes peaked in 1863 and were in decline by 1865. Thousands of newcomers drawn from dozens of countries remained in its wake, some continuing to prospect in the area of Likely and Quesnel Forks. There are two noteworthy aspects of this population influx. First, despite the appearance of a map of newly named locales, very few of the gold rush towns were, in fact, new human settlements. New Westminster (the capital of the new mainland colony), Hope, Yale, Port Douglas, and Lillooet were — like Kamloops — Indigenous village sites before they were newcomer villages and towns. Barkerville and its neighbour Richfield were exceptions, being two of very few entirely new settlements. Second, this population infusion was overwhelmingly young and male, a foretaste of life in a resource-extraction and industrial frontier. The pattern would be reinforced by smaller gold rushes in the Boundary District in 1860, on the Stikine River in 1861-62 (which briefly produced the separate administrative district, Stikine Territory), and in a few smaller pockets in 1871.

Exercise: History Around You — Invasive Species

Thanks to the widely circulated photograph in Figure 13.33, Frank Laumeister has the unfortunate distinction as the man remembered for bringing camels into the Cariboo in the 1860s. He was, no doubt, thinking of their ability to handle freight, their durability in hot climates (which describes the Interior Plateau in the summertime), and the fact that miners used them in California before the B.C. goldrush. The soil, however, was too rocky for their soft feet, the winters were hard on them, and they terrified the horses and mules. These “Cariboo Camels” did not, however, leave much of an impression on the B.C. environment: the last one died around 1905. Thinking of where you are or where you’ve been in Canada, what other “introduced” species of animals and plants might one encounter regularly? Which, if any, have had a serious impact on the local ecology?

Gum Shan, the Gold Mountain

This was, too, the most international community that would be seen in any part of British North America for a century. Thousands of Taishanese could be found in the Cariboo, the two colonial capitals, and the coal mines of Nanaimo. Kanakas were working and living everywhere and increasingly in concentrations on the Gulf Islands. African Americans fleeing slavery and its possible extension to California arrived in large numbers, some establishing a volunteer rifle regiment in Victoria. Continental Europeans, Scandinavians, and even Australians fleshed out the population made up mostly of British, Americans, and even Canadians and Maritimers.

The majority of the gold rush influx, however, exited. For colonists and colonial political figures, the loss of the newcomers meant that the colony was bankrupt and teetering once again on the brink of annexation by the United States. The feeling that British Columbia’s days as a Crown Colony were numbered was particularly strong after the Americans purchased Alaska in 1868. The trappings of imperial power — a few officers of the judiciary (including Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie, who was unafraid of applying gallows law), a Royal Navy base at Esquimalt, and a small legislative council in Victoria — were not entirely reassuring. Voices in the Colonial Office suggested that it was time to cut their losses and hand over the region to the Americans. The Asian population found itself increasingly marginalized physically in the towns and cities as “Chinatowns” appeared, reflecting Euro-North American policies of containment and exclusion. Indeed, as discussion over the wisdom of “confederating” with other British North American colonies and provinces developed, the peoples of British Columbia were roughly a third each of Indigenous, Asian, and European (with Kanakas and Blacks mostly counted among the Whites).

After the Gold Rush

By the mid-1860s, the Indigenous world was in the midst of seismic transformation. The whirlwind of the gold rush years changed much in the region. Newcomer towns appeared and newcomer institutions arose. Newspapermen arrived with their printing presses: the New Westminster British Columbian and the Victoria Daily British Colonist gave voice to familiar Euro-North American ways of understanding law, order, civilization, politics, and power. Catering to a newcomer population, they had little or nothing to say to the majority of people in the region who were Indigenous. According to a study of the impact of colonization on one Indigenous nation,

The most enduring effect of the gold rush was the entrenchment in language and thought of two categories of people, “shama” (semeʔ) and “Indian.” Within a short time the Nlaka’pamux language also had specific terms for Chinese, African American, and Jewish people, but all were shama. Before the arrival of Europeans, the concept of “Indian” simply did not exist. People were simply seyknmx.[2]

The colonial regime certainly distinguished the groups of people under its watch. It was suspicious of Americans, contemptuous of the Chinese, dismissive of Canadians, and uncertain about what it should do with or to the Indigenous population. Douglas did not bring his treaty process to the mainland colony. Historians have theorized that he lacked the budget to do so, needed a larger bureaucracy to manage the time-consuming negotiations (the Nanaimo Treaty took two years to work out), and determined that drawing up generous reserves was a better and more effective way to address the problem than treaties.[3] In 1864 Douglas retired, leaving the outlines of a Native policy but little more. Joseph Trutch (1826-1904) was appointed chief commissioner of Lands and Works and worked under Douglas’s successor on the mainland, Frederick Seymour (1820-1869), to move Indigenous peoples out of the way of settlers and ranchers. When Seymour died, Anthony Musgrave (1828-1888) was appointed to the office of governor, with a mandate to unify the colonies. Musgrave married Trutch’s sister and the brothers-in-law worked to minimize aboriginal title, a process that carried over into the Confederation era.

Almost overnight, Indigenous people lost a variety of liberties and freedom of movement. Douglas had promised to protect their villages, farms, and homes; Trutch actively sought to dispossess them. How could this happen only a few short years after the Nlaka’pamux, the Secwepemc, and the Syilx (Okanagan) demonstrated considerable military ability and capacity? The answer is a familiar one: smallpox.

Key Points

- The British Columbia gold rush consists of distinct phases including the pre-1858 mining of gold by Indigenous people, the 1858-59 stampede into the Fraser Canyon, and the 1860-63 Cariboo phenomenon.

- The gold rush brought roughly 20,000 newcomers into the mainland colony. This population comprised people from around the world.

- The presence of large numbers of Americans posed a threat to British sovereignty, and the Colonial Office responded with strategies aimed at entrenching British power.

- New colonial institutions and the physical disruption entailed in the gold rush had severe repercussions for Indigenous peoples in south and central British Columbia.

Attributions

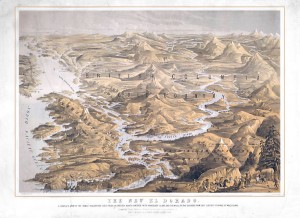

Figure 13.30

BC-New_Eldorado by DarkEvil is in the public domain.

Figure 13.31

Chinese man washing gold by LibraryArchives is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 13.32

Barnards Express at Yale by Ras67 is in the public domain.

Figure 13.33

Cariboo camel by Magnus Manske is in the public domain.

- Daniel P. Marshall, “No Parallel: American Miner-Soldiers at War with the Nlaka’pamux of the Canadian West,” in John M. Findlay and Ken S. Coates, ed., Parallel Destinies: Canadian-American Relations West of the Rockies (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 64-65. ↵

- Andrea Laforet and Annie York, Spuzzum: Fraser Canyon Histories, 1808-1939 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998), 56-7. ↵

- Cole Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002), 32-37. ↵