Chapter 2. Indigenous Canada before Contact

2.5 Languages, Cultures, Economies

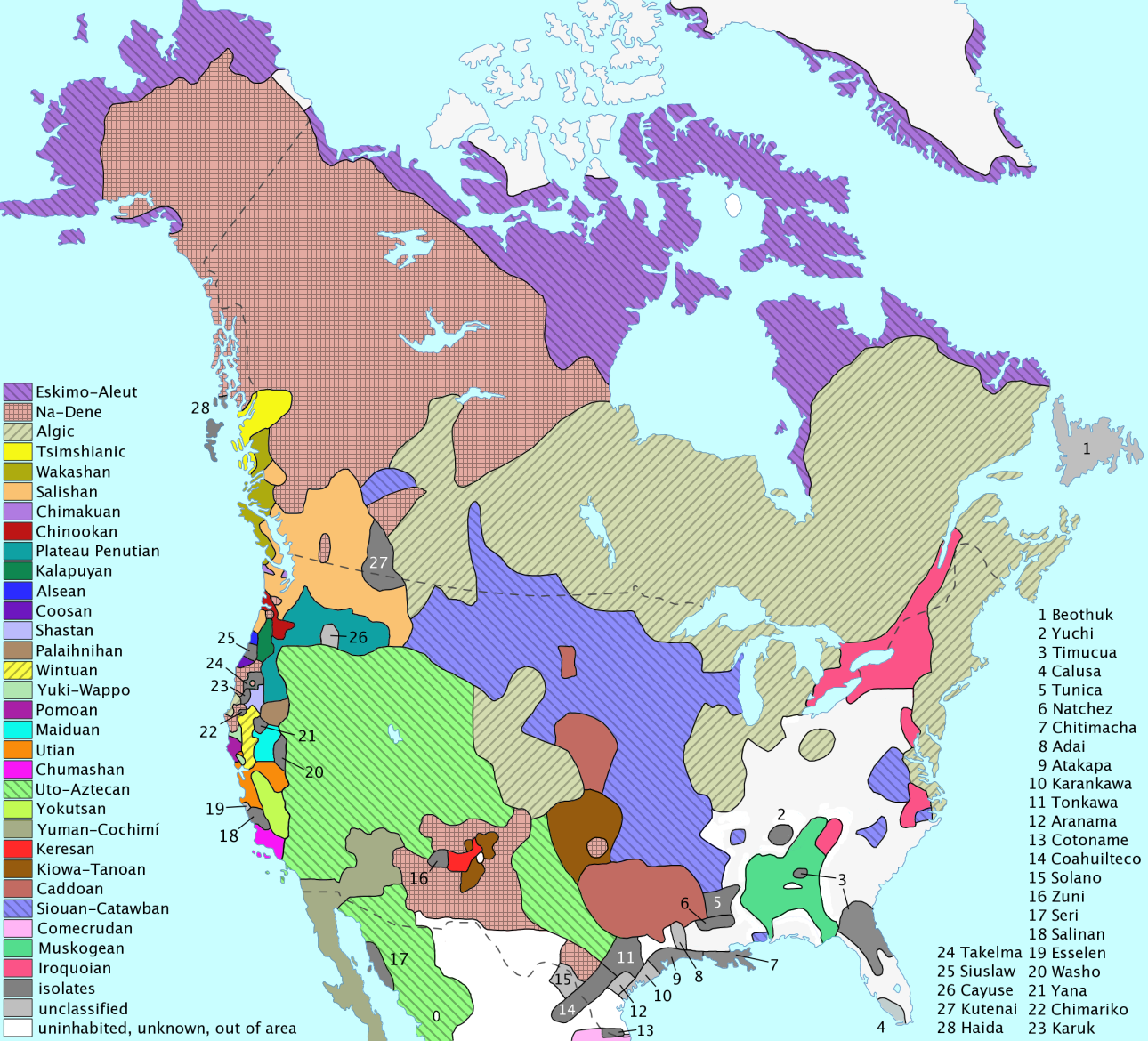

These brief histories of Indigenous peoples and societies reveal that categorization is complicated. Take language, for example, which is often used as a key element of nationality (e.g., French people speak French and live in France and almost everyone in France speaks French). For Indigenous peoples, there are no political units that encapsulate the whole of the largest and most widespread language groups in Canada. As the maps in Figures 2.12 and 2.13 show, the two most widely spoken language groups before contact — Athabascan or Na-Dené and Algonquian — cover massive areas and include societies that were separated by huge distances. Na-Dené dialects are spoken by Apache and Navajo in the American southwest, as well as by peoples from Alaska’s Łingít (Tlingit) to Alberta’s Tsuu T’ina (or Sarcee) who migrated south onto the Plains in the early 1700s. Similarly the Algonquian-speakers are represented by agricultural societies, bison hunters like the Siksika (Blackfoot), and lowland fisher-hunter peoples like the Cree, the Mi’kmaq, and the Anishinaabe, as well as large populations (some of them agriculturalists) in what is now the United States. Within these two language areas, dialect differences can be very great, but the core elements of the language mostly survive.

One of the challenges facing anyone interested in Indigenous language groups is that European contact was a catalyst for migration, generally in a westward direction. European observers were, thus, recording the presence of language groups whose more recent homelands in some cases were somewhere else. Figure 2.14 gives a sense of the huge diversity of language groups in North America but no sense at all of the internal diversity within the broad linguistic categories.

Pre-Contact Societies

Agriculture, horticulture, foraging, hunting, and fishing were key features of the economies of the pre-contact Americas. In Canada, rocky, stingy, or hard-packed soils (like those on the Prairies) made agriculture all but impossible (as did, of course, the climate in many zones). Despite some mastery in metalwork, as evidenced in silver, gold, and copper decorative arts, the knowledge and skills necessary to produce iron tools that would give agriculture a lift were not available. “Digging sticks” used to drill seed holes are far more labour intensive but less demanding on the soil than wooden or metal ploughs. This is not to say that agriculture is the higher form of economic activity in a pre-industrial world. Farming societies have many advantages, such as the ability to achieve rapid and substantial growth, the wherewithal to build villages and armies, political sophistication of a particular kind, and so on. But they also have significant health issues, less flexibility in the event of famine or drought, and are at more risk of being attacked by enemies. Indigenous economies were far more adaptable in this respect than their Old World contemporaries.

What is more, everyone participated in commerce. These were trading societies that augmented their output with goods from their neighbours. Sometimes these were raw materials, such as furs or maize, flint or wampum; other times they were crafted goods like clothing, hides, or the much-sought-after sinew-backed bows made by the Shoshone. Everywhere one looks, the archaeological evidence turns up exotic artifacts in village sites, indicating a rich intercommunity and intercultural life that dates back thousands of years. For example, red ochre suitable for rock painting and other uses as a dye was mined for centuries from caves in the Similkameen Valley in southern British Columbia; it shows up in pictographs as far afield as Arizona.

Exercise: History Around You — Indigenous History Where You Live

In Vancouver’s Stanley Park there is a clutch of totem poles arranged near the old cricket oval on Brockton Point. It is a favourite spot for tourists to stop for photographs. The display became much more complex and informative in preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympics. However, a long-standing complaint was that the poles were not examples of local, Coast Salish work, but rather, northern Kwakwawa’wakw and Ts’msyan styles. In other words, the people who used to live on Brockton Point (and whose graveyards remain nearby) were excluded from this display of “native” history.

How is Indigenous history depicted in your community? Is there a museum or gallery dedicated to the subject? Is there one on a nearby reserve? Do a mental inventory of the statues and memorials and plaques in the community: how many of those pertain to the experiences of indigenous people? Do they get it right? (If you’re not in Canada, consider paying a visit to the consulate or embassy — if one’s nearby. How is the nation’s Indigenous heritage represented?)

Populations

Given the fragmentary nature of the evidence, even semi-accurate pre-Columbian population figures are impossible to obtain for the indigenous populations prior to colonization. Estimates are extrapolated from small bits of data. Recent research suggests that the 13th century marked a critical break in the demographic history of North America. As the climate changed for the worse and the little ice age began, populations struggled to survive famine and competition for resources intensified. It has been suggested that peak pre-contact population numbers may have occurred two or three centuries before contact.[1]

In 1976, geographer William Denevan used the existing estimates to derive a “consensus count” of about 54 million people for the Americas as a whole.[2] There is, however, no “consensus.” Estimates for North America range from a low of 2.1 million (Ubelaker 1976) to 7 million people (Thornton 1987) and even to a high of 18 million (Dobyns 1983).[3] The Indigenous population of Canada during the late 15th century is estimated to have been between 200,000 and 2 million, with a figure of 500,000 currently accepted widely. These numbers are utterly conditional: on the West Coast alone estimates range from 80,000 (c. 1780) to 1.6 million, although the evidence to support either the low count or the high count is sparse.[4] Nonetheless, if the widely touted figure of 350,000 for British Columbia is reckoned as fair, then the national figures would jump up by as much as 200,000 (a 40% increase on the widely accepted figure of half a million)! Thus, there are significant discrepancies.

As we shall see in Chapter 5, the contact experience brought with it terrible disease epidemics that raced ahead of the Europeans in the proto-contact period. It is important to note here that the work of historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, and others — often supported by oral testimony from Indigenous sources — suggests that the pre-contact Americas were not disease-free. Contagious diseases included tuberculosis, hepatitis, and respiratory infections. Syphilis and gastrointestinal illnesses might also belong to this list. And there were, in parts of the Americas, significant numbers of parasites. With the exception of tuberculosis, however, none of these are proper epidemic diseases. Syphilis, for example, spreads only on a one-to-one basis through intimate contact between individuals; influenza, by contrast, can be transmitted by one infected individual to dozens of other hosts at a time by the simple means of coughing. For the most part, then, experience with epidemics was both limited and very different from what Asians, Africans, and European humans witnessed regularly. This lack of knowledge meant that Indigenous societies were badly unprepared for highly contagious disease epidemics. It does not mean, however, that life expectancies were particularly good. All indications suggest that, as in most human societies, a person was lucky to reach 30 years of age and very fortunate to reach 50. If infant mortality levels were higher in the Americas (and evidence suggests they were) it wasn’t helped by extended breastfeeding practices. Probably in most Indigenous societies, infants were nursed for four years. This custom has an effect beyond nourishment and hydration: prolonged breastfeeding reduces fertility. Fewer infants may have generated more intensive childcare overall but, obviously, dampened fertility rates placed an upward limit on population growth rates. This would prove a critical weakness when it came time to recover from epidemic depopulations.[5]

Key Takeaways

- Indigenous societies at contact defy simple categorization by language, economic activity, or location.

- Population estimates suggest that humans were very numerous in the Americas in the late 1400s but perhaps not as numerous as they were even a century earlier.

Long descriptions

Figure 2.12 long description: Before contact, speakers of Na-Dené languages could be found in most of modern northwestern Canada, including the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and the northern parts of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, but excluding Nunavut and the northern coast of Canada’s three territories. Na-Dené languages were also spoken in central Alaska, along the California coast, and in some of the southern United States. [Return to Figure 2.12]

Figure 2.13 long description: Before contact, speakers of Algonkian languages could be found in most of modern eastern Canada, including Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and much of Labrador and Quebec. Algonkian languages were also spoken in parts of southern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, as well as small parts of the central and northeastern United States. [Return to Figure 2.13]

Figure 2.14 long description: Map showing the distribution of Indigenous languages in North America before contact. This description uses modern political terms to demonstrate where languages were spoken.

The map depicts the following language families:

- Eskimo–Aleut: Spoken along the coast of Alaska, the northern coast of the Northwest Territories, throughout Nunavut, along the northern and western coasts of Quebec, on the northern coast of Labrador, and along the coast of Greenland.

- Na-Dené: Spoken throughout the interior of Alaska, all of the Yukon, the interior of the Northwest Territories, northern British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, another sliver of Alberta near the Rocky Mountains, a few tiny areas along the coast of California, and throughout New Mexico and parts of Texas, as well as in Oregon and Washington along the Columbia River.

- Algic: Spoken in southern to mid-Alberta, parts of southern Saskatchewan, most of Manitoba, all of Ontario, nearly all of Quebec, plus New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and the eastern United States from New England to Virginia, as well as Michigan, Illinois, part of Ohio, and an area including Wyoming.

- Tsimshianic: Spoken in a small region on the coast of northwestern British Columbia, crossing just barely over the border with Alaska into the Aleutian Islands. This language family was spoken along the Skeena River and on a few small islands to its south.

- Wakashan: Spoken in parts of the southern coast of British Columbia, including the area immediately to the south of the Tsimshianic range, as well as the western half of Vancouver Island, and the northwesternmost tip of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state.

- Salishan: Spoken throughout southern British Columbia, including the eastern half of Vancouver Island, the Lower Mainland, the southern Interior up until the Kootenays, and one little area on the west coast between two Wakashan regions. This language family is also spoken throughout much of northern Washington state and the Olympic Peninsula and one coastal region in Oregon, just south of the mouth of the Columbia River.

- Chimakuan: Spoken in two small regions on the west and east coasts of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state.

- Chinookan: Spoken in Oregon along the Columbia River, which leads to the west coast of Oregon. The range of this language family culminates around Portland, Oregon.

- Plateau Penutian: Spoken in southern Washington, north-central Oregon, two regions in central and southern Oregon, the northeast corner of California, and an area overlapping the southeast corner of Washington, the northeast corner of Oregon, and central Idaho.

- Kalapuyan: Spoken in the Willamette Valley of western Oregon, stretching south from Portland.

- Alsean: Spoken in one small area on the central coast of Oregon.

- Coosan: Spoken in one small area on the southern coast of Oregon.

- Shastan: Spoken in northern California and southern Oregon.

- Palaihnihan: Spoken in northeastern California.

- Wintuan: Spoken in the Sacramento Valley of the interior of northern California, which is just east of San Francisco.

- Yuki–Wappo: Spoken in two small areas on the coast of California.

- Pomoan: Spoken in one small area on the coast of California, wedged between the two Yuki–Wappo areas.

- Maiduan: Spoken in one mid-sized area in northeastern California.

- Utian: Spoken in one U-shaped area in central California, with one half of the U being on the coast and the other being in the interior.

- Chumashan: Spoken in one region on the southern California coast, including three tiny islands.

- Uto–Aztecan: Spoken throughout the western and southwestern United States, including southeastern Oregon, southern Idaho, much of eastern California, and parts of Nevada and Utah. This language family was also spoken in a sizeable chunk of Texas, as well as an area beginning in southern Arizona and continuing south across the border into western Mexico.

- Yokutsan: Spoken in one interior region in central California.

- Yuman-Cochimí: Spoken in the southern tip of California, western Arizona, and on the Baja California Peninsula, which is a narrow strip of Mexican land protruding from the southern part of the state of California.

- Keresan: Spoken in a small region in northern New Mexico.

- Kiowa–Tanoan: Spoken in small regions in northern New Mexico and one larger region covering parts of northern Texas and western Oklahoma.

- Caddoan: Spoken in parts of the central United States, including a small region in South Dakota, a region stretching from central Nebraska south to northern Kansas, and a larger area covering eastern Texas, southern Oklahoma, southwestern Arkansas, and northern Louisiana.

- Siouan–Catawban: Spoken in many areas of the United States, particularly the Midwest, and a few areas in Canada. Specifically, this language family was spoken in southeastern Montana, northern Wyoming, North Dakota, southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and one area in western Alberta. This language family was also spoken in South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and in eastern Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Smaller areas where this language family was spoken include a spot on the southern coast of Mississippi and a few smaller regions in North and South Carolina.

- Comecrudan: Spoken in the northernmost part of eastern Mexico, on the border with Texas.

- Muskogean: Spoken in the southeastern United States, including parts of Alabama and Georgia.

- Iroquoian: Spoken in the eastern United States and eastern Canada. This includes along the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, around Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, and in New York state. Other smaller regions where this language family was spoken include one stretching from central Pennsylvania to Maryland, one near the coast of North Carolina, and one overlapping western North Carolina, northern Georgia, and northwestern South Carolina.

The map distinguishes language isolates (languages without evidence of being related to any other language) and unclassified languages (languages that have not been proven to be affiliated with any other).

Language isolates depicted include:

- Yuchi: Spoken in one small area in the southeastern United States, approximately around Kentucky or Tennessee.

- Timucua: Spoken in one small area in northern Alabama, within the region where the Muskogean language family was spoken, and in a larger region covering southern Georgia and northern Florida.

- Tunica: Spoken in southwest Mississippi or central Louisiana.

- Natchez: Spoken in southwest Mississippi or central Louisiana, in the area directly below the range of the Tunica language.

- Chitimacha: Spoken along the southern coast of Louisiana.

- Atakapa: Spoken in one area along the coast in southwestern Louisiana and eastern coastal Texas.

- Tonkawa: Spoken in one small area in eastern Texas.

- Cotoname: Spoken in one tiny area overlapping the border between the southern tip of Texas and eastern Mexico.

- Coahuilteco: Spoken in one area stretching from southwestern Texas across the border into eastern Mexico.

- Zuni: Spoken in one small area along the border between New Mexico and Arizona.

- Seri: Spoken in one small area along the northwestern coast of the main part of Mexico (excluding the Baja peninsula).

- Salinan: Spoken in one small area on the central coast of California.

- Washo: Spoken in one small area on the border between California and Nevada.

- Yana: Spoken in one tiny spot in north-central California.

- Chimariko: Spoken in one tiny spot in northwestern California.

- Karuk: Spoken in one small area in northwestern California.

- Takelma: Spoken in one small area in southwestern Oregon.

- Siuslaw: Spoken in one small spot on the coast of southwestern Oregon.

- Kutenai: Spoken in one small area covering part of the Kootenays in southeastern British Columbia and parts of northern Idaho and Montana.

- Haida: Spoken along the central coast of British Columbia, around Prince Rupert and south of the Aleutian Islands.

Unclassified languages depicted include:

- Beothuk: Spoken on the island of Newfoundland.

- Calusa: Spoken in southwest Florida, around where Everglades National Park now is.

- Adai: Spoken in one small area in northwestern Louisiana.

- Karankawa: Spoken in one small area in eastern coastal Texas.

- Aranama: Spoken in one small area in eastern Texas, wedged between the Karankawa, Tonkawa, and Coahuilteco language ranges.

- Solano: Spoken in one area straddling the border between southwestern Texas and northeastern Mexico.

- Esselen: Spoken in one tiny spot on the central coast of California.

- Cayuse: Spoken in one small area in northeastern Oregon.

Media Attributions

- Distribution of Na-Dené language speakers, pre-contact © 2005 by ish ishwar is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Distribution of Algonkian language speakers, pre-contact © 2005 by ish ishwar is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Pre-contact distribution of Indigenous language families © ish ishwar is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Kwakiutl Chief at the Ethnological Museum © FA2010 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: U of R Press, 2013), 2. ↵

- William M. Denevan, The Native Population of the Americas in 1492 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976). ↵

- Douglas H. Ubelaker, “North American Indian Population Size: Changing Perspectives,” in Disease and Demography in the Americas, eds. John Verano and Douglas H. Ubelaker, (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1992), 172–3; Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History since 1492 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987); Henry F. Dobyns, Their Number Become Thinned: Native American Population Dynamics in Eastern North America (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1983). ↵

- John Belshaw, Becoming British Columbia: A Population History (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), 72–6. ↵

- Roderic Beaujot and Don Kerr, Population Change in Canada, 2nd edition (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2004), 21. ↵