Chapter 3. The Transatlantic Age

3.6 France in the Americas

The Spanish literally struck gold in the Caribbean and in the Aztec Empire. The torrent of gold and silver plunder flowing into western Europe changed the continent overnight. Until the 16th century, Iceland, the British Isles, and northwestern France were perceived by the commercial and political leaders of the great Eurasian capitals as the farthest reaches of trade networks, backwaters of economic stagnation with little to offer the rest of the world. In terms of wealth measured in spices or precious metals, northwestern Europe was regarded as impoverished and wanting. Spanish coups in the Americas (both political and economic, not to mention territorial) did two things: they invigorated the economies of Europe and fuelled interest in further imperial ventures. What if similar riches existed in the northern continent?

French Expeditions

French imperial activity in the New World got off to a poor start. The earliest official French expeditions to North America, and particularly to Canada, were largely forgettable ventures. The first voyages, led by Jacques Cartier between 1534 and 1542, made contact with local peoples, including the Mi’kmaq, Montagnais, Algonquin, and the St. Lawrence Iroquois. Cartier’s mission followed Pizarro’s by only two years. Significantly, Cartier was instructed to “discover certain islands and lands where it is said that a great quantity of gold and other precious things are to be found.”[1] Clearly the French Crown would have liked nothing better than to copy the success of the Spanish. These early voyages, however, established that the area contained no bounty of natural or human resources that was valuable to the French at the time. There was, simply put, no gold.

What Cartier came across instead was a region in economic transition. French fishermen had already scouted out North America at least as far as the Gaspé Peninsula, the south shore of the St. Lawrence River at its entrance to the Gulf. When Cartier’s first expedition rounded the northern tip of Newfoundland and arrived in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, he found the local people eager to trade with him and clearly aware of a French interest in obtaining furs. This was a sure sign that there had already been contact between Indigenous peoples and European fishing/whaling fleets, and that some of the contact relationship involved commerce. The Algonquin people Cartier encountered indicated that they preferred some European goods over others, a sign that they were becoming knowledgable about the newcomers.

Cartier made contact with St. Lawrence Iroquois on the Gaspé, where he offended his hosts by erecting a large cross bearing the words, “Long Live the King of France.” A year later he returned, venturing into the St. Lawrence River and moving westward. At this time many small villages dotted the north shore of the river in particular, especially near Île d’Orléans. Cartier’s team visited the largest village, which he regarded as the “capital” of the St. Lawrence Iroquois, near the site of present-day Quebec City. This was Stadacona and its chief was Donnacona.

Cartier’s relationship with the St. Lawrence Iroquois, and especially with Donnacona, was not especially civil. On his first visit, Cartier attempted to abduct several of the Stadaconans, believing that they would make excellent proof of the success of his voyage. He even tried to abduct Donnacona himself, but settled for his two sons, Taignoagny and Domagaya. They travelled back to France where they spent the winter before returning to Stadacona in the summer of 1535 as part of Cartier’s second voyage.

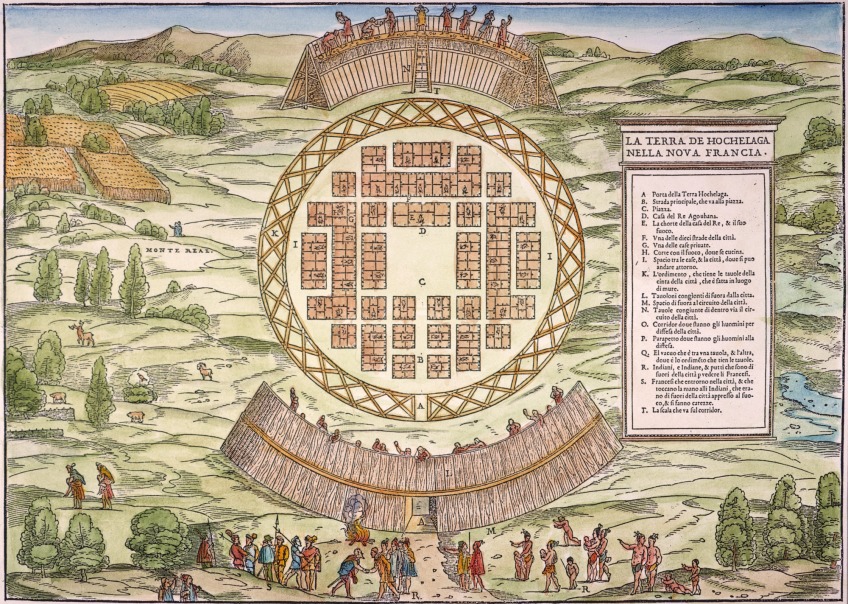

It was during this second tour that Cartier travelled farther upriver to another large settlement, Hochelaga. Unlike Stadacona, Hochelaga was fortified with a triple palisade of wood. The town contained about 3,000 people and was surrounded by cornfields. Its location remains a source of debate, but there is general agreement that it was near the foot of what Cartier called Mount Royal (that is, Montreal), though on which side is uncertain. A drawing made subsequently of Hochelaga by a European artist working from Cartier’s descriptions suggests an Italianate order, which most likely was the artist’s invention. Nevertheless, its 50 longhouses (each perhaps 30 metres deep) are represented. Hochelaga would have been an important meeting place at or near the confluence of the Ottawa/Outaouais River, the Rivière des Prairies, and the St. Lawrence, abutting Algonquin territory to the north, Mohawk lands to the south, and Stadaconan territory to the east. Those three palisades, however, strongly suggest a community living in the shadow of violence and warfare.

Cartier’s expedition returned downriver to Stadacona, where they spent an especially cold and difficult winter. Most of the crew died from cold and scurvy. The good news was a cure provided by the Stadaconans that mitigated the vitamin C deficiency that causes scurvy and without which the whole of the French expedition would have been doomed. Despite Cartier’s erratic and consistently ungrateful behaviour toward the St. Lawrence Iroquois, and despite losing about 50 of his own men — evidently to ailments introduced by the Europeans — Donnaconna supported the foreigners through the winter. The Iroquoian leader made the mistake of telling Cartier about metal sources upriver (likely copper around Lake Superior) and this set off Cartier’s gold fever. The reduced French party would have to be reinforced and in order to do that Cartier would have to first return to France and sell the court of Francis I on the idea of further investment. To that end, and with an eye to supporting a local coup, Cartier abducted Donnaconna, his sons (again), and seven other Stadaconans and took them all to France. Nine of the ten perished, and the tenth never returned to Canada.

Although Cartier received a warm welcome in Stadacona when he returned for the last time in 1541, that feeling did not last long. In that year the French made the last attempt of the century at establishing a colonial foothold in Canada. Cartier led a settlement cohort of 300 French to Charlesbourg-Royal, a site now identified as at Cap Rouge near Stadacona, but the settlement lasted barely a year, beset as it was by bad weather and hostility from the Stadaconans whose hospitality and generosity Cartier had repeatedly scorned.[2]

Cartier’s account of his 1541 voyage is silent on Hochelaga, from which scholars conclude that the town was gone by then. It may have been destroyed by enemies or disease, but it was the practice of Iroquoian farmers to move their villages every few years to find locations with better soil and to escape the accumulation of waste and vermin that beset older settlements, so it may have been dismantled and rebuilt elsewhere. At the present time — and perhaps forever — the fate of Hochelaga remains unknown.

The lacklustre interest on the part of the French in setting up a trading post in the St. Lawrence can be explained by a number of factors. First, Spain had a head start in the Americas and was vigorously protecting its foreign monopoly. This was evident even in the Gulf of St. Lawrence where, after 1543, the Basque whaling fleet — made up of very large, well-armed and generally intimidating ships — “fulfilled [Spain’s] geopolitical aim of controlling the gateway to the gulf at [a] time of transatlantic rivalry….” The rise of New France in the next century allows us to lose sight of this Spanish initiative and its strength in the second half of the 15th century: “For the next 35 years, while the French shelved their explorations, the Strait was the scene of a whaling industry of unprecedented scope and intensity, centred at Red Bay” on the Strait of Belle Isle.[3] It was fortunate for French interests that the Spanish, Basques, and Portuguese overwhelmingly pursued their maritime interests in the offshore fisheries. They had enough salt at their disposal to process their catch without making landfall and, under those conditions, had no real reason to establish even a toehold. Second, Cartier disappointed his sponsors with samples of quartz and iron pyrites from Canada, which he very optimistically claimed were, respectively, diamonds and gold. (Hence the origin of the French saying, “as false as a diamond from Canada.”) He never found the mythological Kingdom of the Saguenay, which his St. Lawrence Iroquoian hosts painted as a city of gold to rival the Inca capital at Cuzco. Finally, in the latter part of the 16th century, the Wars of Religion distracted the French from further overseas efforts in Canada. Anyone reflecting on the French experience in North America to 1600 would be safe in concluding that it had been a failure and perhaps was over.

Florida

As a result of Cartier’s unpromising expeditions, the French retreated from the North and spent much of the next 50 years trying to establish themselves elsewhere in the Americas. In an effort to emulate the success of the combative Dutch, the French turned their attention to Portuguese-claimed territory in Brazil. They established a position at Rio de Janeiro (“France Antarctique”) in 1555 and another much later in 1612 at São Luís (“France Équinoxiale”). Nothing came of either effort.

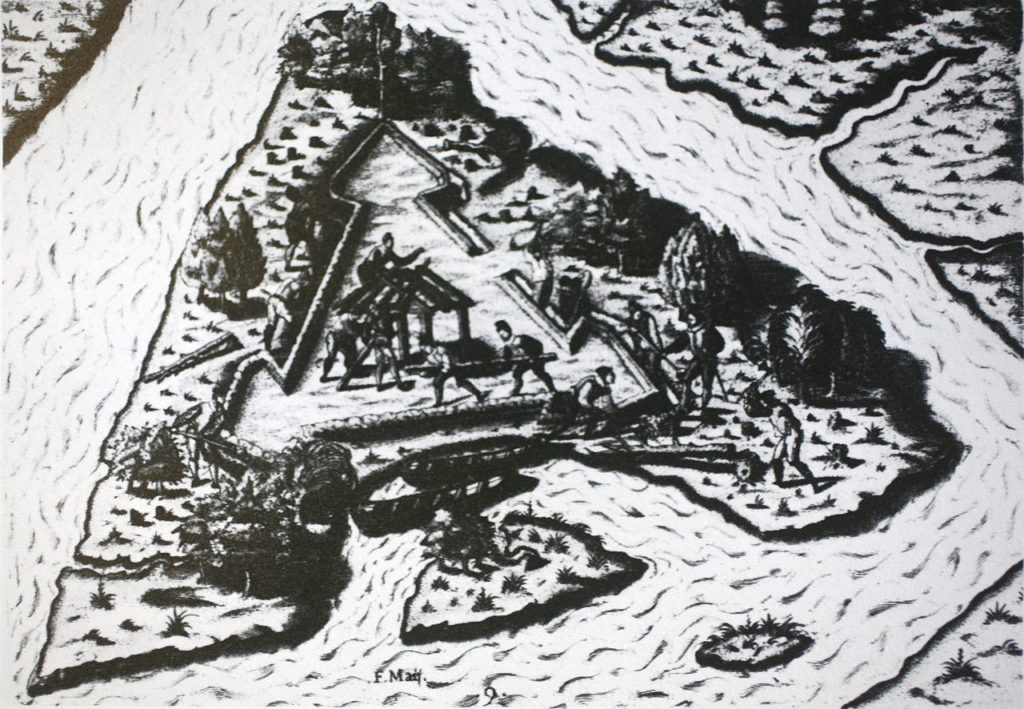

There was slightly more promise in the prospect of a colony in Florida, which was then controlled by Spain. The ambitious goal in this instance was to weaken the Spanish political hold on the Americas as a whole. In 1564, René Goulaine de Laudonnière led an expedition to Florida, establishing Fort Caroline at the mouth of the St. Johns River in Timucuan territory near modern-day Jacksonville. Florida’s proximity to the rich Spanish Caribbean made it a strategically important position from which relatively easy wealth could be won. The French hoped to establish a successful settlement there, and thus a stepping-off point to contest Spanish power in the Caribbean. A foothold in Florida could also provide the opportunity to weaken the Spanish Crown through piracy; the prevailing currents and winds of the Caribbean and Atlantic ensured that the treasure fleets travelled up along the Florida coast before venturing out across the Atlantic. The settlement at Fort Caroline also reflected French concerns at home. Rising religious tensions between Catholics and Huguenots (Protestants) made it attractive to send Protestants to Fort Caroline where they could have refuge while, at the same time, serving France.

The Spanish, hearing of the French incursion into Spanish territory, established their own colony just south of Fort Caroline at San Agustín (St. Augustine). A September 1565 expedition against the French settlement quickly overwhelmed their defences and the Spanish killed many of the men, sparing most of the women and children. Twenty-five of the Frenchmen escaped, making their way along the Florida coast. The Spanish caught up to them about 15 miles outside of St. Augustine, where Pedro Menéndez de Avilés offered the Protestant Huguenots the chance to renounce their “apostate” faith and embrace Catholicism; their refusal was part of what sealed their fate. The men were executed and Spanish dominance in Florida was secured. The massacre of the French settlers and soldiers marked the end of the French experiment in Florida and their attempts to undermine Spanish political control in the area.

Failure in Florida would cause the French to revisit the possibility of colonies in Canada, although a generation would pass before a new French effort in the north came to pass. In the interim, French fishing boats were still making the voyage to the Grand Banks fisheries and they continued to encounter Indigenous people who wished to trade. French merchants soon realized the St. Lawrence region was a reliable and rich source of valuable fur-bearing animals, especially the beaver, which were becoming rare in Europe at a time when it was fashionable to wear fur hats. Encouraged by the merchants of its Atlantic ports, the French Crown decided to colonize the territory to secure and expand its influence in America.

Key Takeaways

- The Spanish and Portuguese conquests in the Americas resulted in rapid economic growth in northwestern Europe, thus enabling and encouraging competitive missions from England, France, and other countries.

- Cartier’s missions to the St. Lawrence brought back little of wealth but they represent the first sustained and documented contacts between Europeans and Indigenous peoples in what becomes Canada.

- The French failed to establish an ongoing presence in the north and in Florida. France retreated from the field for the rest of the century.

Media Attributions

- Jacques Cartier stamp © 1934 by George Arthur Gundersen is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) village of Hochelaga © 1556 by U.S. National Library of Medicine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Founding of Fort Caroline © unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Quoted in Thomas McIlwraith and Edward Muller, North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent (Washington, DC: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001), 67. ↵

- Arthur J. Ray, I Have Lived Here Since the World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada's Native People (Toronto: Key Porter, 1996), 51–53. ↵

- Brad Loewen and Vincent Delmas, “The Basques in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Adjacent Shores,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology 36, issue 2 (2012): 223. ↵

The village of the St. Lawrence Iroquois at or near the current site of Quebec City.

St. Lawrence Iroquoian fortified town at or near what is now Montreal.

According to Donnacona and other Stadaconans, a wealthy settlement north of the Laurentian Iroquois territories. Perhaps mythical, perhaps meant to distract or deceive the Europeans, the story may have legitimate roots in an oral tradition now disappeared.

A series of wars fought in Europe arising ostensibly from divisions within Christianity. The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) distracted the Crown from transatlantic enterprises.

Established by the French in 1564, it is reckoned to be the oldest fortified European settlement in what is now the United States.