Chapter 4. New France

4.5 The Heroic Age of New France

The first 50 or 60 years of French colonial activity in Acadia and the St. Lawrence were challenging but also quite lucrative. There was a degree of independence from the Crown that allowed colonial leaders, entrepreneurs, and even common settler/traders a significant amount of latitude, for good or ill. This was, too, a period in which Indigenous neighbours and hosts were trying to decide whether they were better off with or without the Europeans. The Five Nations decided early on that the French were unwelcome, and this made the colonial enterprise all the more tenuous.

It is a reflection of these conditions that the colonial phase from around 1600 to 1663 has long been described as the “heroic age of New France.” In terms of building a patriotic myth around the French presence, this has been a useful storyline. It overlooks the fact that French heroism would have counted for little had it not been for the aligned interests of Indigenous neighbours and hosts. Historians in a post-colonial era tend to eschew the idea that there was much “heroic” to an invading band of merchants whose presence resulted mainly in cultural and demographic losses among the Indigenous peoples. Chapter 5 accordingly looks at aspects of the Indigenous experience in this period. It is, however, worth considering the circumstances facing the French interlopers in this period and how they met the challenge. No one more represents the pre-royal phase than Champlain.

Samuel de Champlain

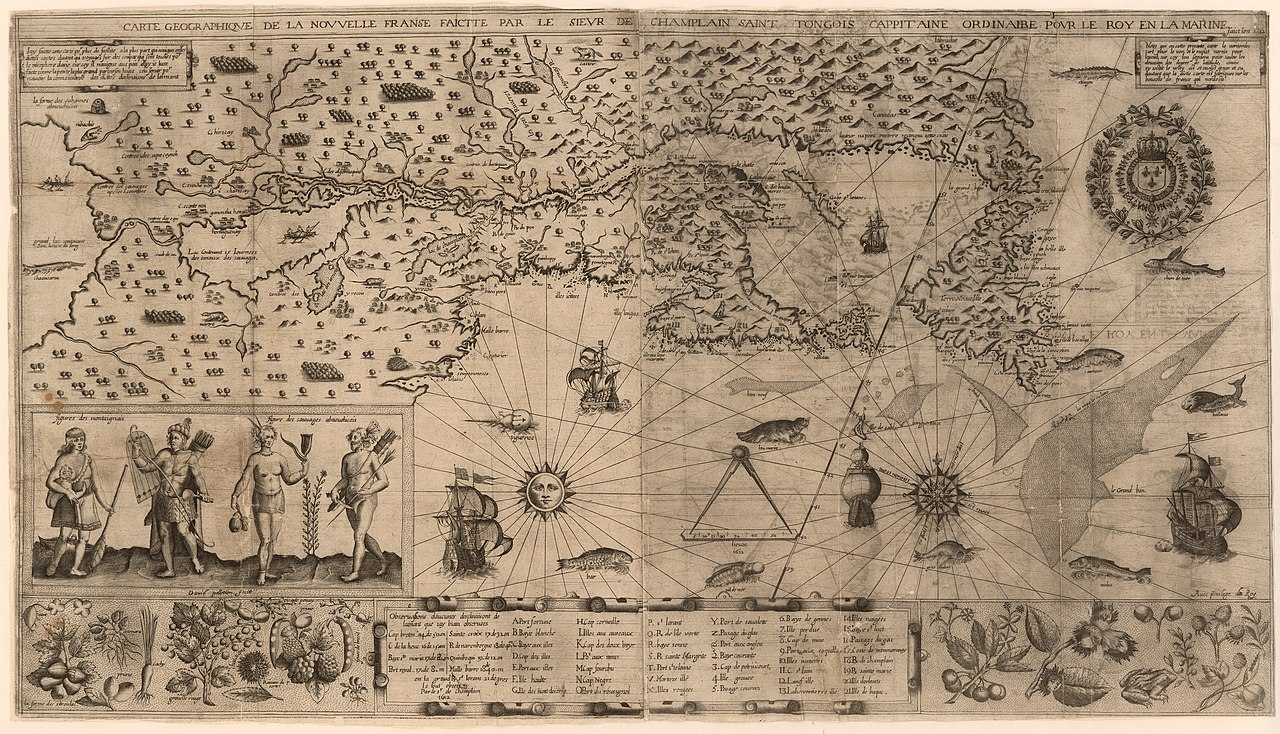

Samuel de Champlain (1574–1635) deservedly attracts attention. His early years remain shrouded in mystery — although he was almost certainly born a Huguenot at the end of the Wars of Religion. He may have travelled with Spanish ships to Brazil and Mexico, but the evidence is uncertain. By the time he was in his 30s he was regarded as an accomplished geographer and draughtsman and was receiving a royal pension which, along with an inheritance, allowed him to pursue his interests. It was as a cartographer, it seems, that he was first sent across the North Atlantic by France. There, he quickly acquired additional responsibilities. The first winters spent by the French in Acadia and Quebec were very hard. The weather was cold beyond the expectations and experiences of the French and, 70 years after Cartier’s ordeal, scurvy continued to plague them. Champlain, however, proved to be indefatigably curious, talented, and resourceful.

Faced with another long and depressing winter in Acadia in 1606, Champlain established l'Ordre de Bon Temps (the Order of Good Cheer), the principal objective of which was defeating the mid-winter blues with regular feasts, performances of plays, and other entertainment. In his late 30s, if not his early 40s, he joined in on regional wars as a leader and a combatant. On separate occasions he took an arrow in the neck and two in the knee. Around the same time he sought to impress his Wendat and Algonquin friends by shooting the rapids at Lachine in a canoe, which he accomplished successfully. He travelled wherever and whenever the opportunity presented itself and he drew beautiful maps of the lands he visited. He listened well to Indigenous companions and noted that his informants claimed that Hudson Bay was not the Pacific Ocean but a gulf coming off the Atlantic — many years before the British proved to the satisfaction of Europe that this was the case.

His goals were materialistic and his moral code was flexible when it came to finding wealth in Canada. Indeed, he married a 12-year-old, Hélène Boullé, in Paris not for love or even for companionship, but for the dowry she brought with her. Their marriage was not consummated (if it ever was) until Hélène was 14. She never bore any children, so Champlain adopted three daughters from the Algonquin nation in the late 1620s.

Champlain died in Quebec in 1635 at the age of 59 or 60 years, a devout convert to Catholicism who spent a lifetime skillfully walking the tightrope between sectarian division in his native France. After 30 years off and on in the colonies, Champlain had done much to shape the expectations of France and relations with Indigenous peoples, both of which had enormous implications and a very long legacy.[1]

Exercise: Think like a Historian — Biography and Context

Take a look at the biography of either Samuel de Champlain, the Comte de Frontenac, or Jeanne Mance in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Write a 200-word obituary for one of them. In doing so, assume the voice and perspective of someone who occupied a social position either above, below, or level with your subject. Also, consider what the measure of these individuals was in their time.

Feel free to present a critical account — as long as it’s based on fact. As an exercise, this will help develop your ability to select and compress information in tight prose; it also obliges you to look at someone in the past within their historic context. For example, Frontenac didn’t care whether he had voter support — he functioned in a non-democratic environment — so it wouldn’t make sense to say that he should have gone to the polls and campaigned for public approval.

Key Takeaways

- The period between 1600 and 1663 is sometimes described as the “heroic age” of New France.

- The French colony was built around a particular kind of commerce in an age of religious combativeness and rising merchant power, all of which gave form to the colony of Canada.

Media Attributions

- Map of New France © 1612 by Samuel de Champlain is licensed under a Public Domain license

- An excellent source on Samuel de Champlain is Marcel Trudel's “Samuel de Champlain” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/champlain_samuel_de_1E.html . ↵

The Order of Good Cheer was suggested by Champlain in 1606 as a means of improving morale among the residents at Port-Royal. It is reckoned that the first meeting of the Order constitutes the first performance of European-style theatre in North America.