Chapter 4. New France

4.6 Canada, 1663–1763

The years between 1649 and 1663 boded ill for Canada while, simultaneously, they offered new opportunities. Wendake’s (Huronia’s) collapse and dispersal eliminated the very backbone of the trade network on which the French relied. The Haudenosaunee weren’t finished there, as they pursued their goal of territorial control across all of southern Ontario and the Ohio Valley. The loss of Wendat support sent a chill through Canadien villages and trading houses, but it also opened up the possibility of a market for colonial farm products. Canada was in a position to become what Wendake (Huronia) had been: the granary of the north. The coureurs de bois, moreover, had by now plunged deep into the interior of the continent by means of the river and lake systems that (including a few portages) joined the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Louisiana and Hudson Bay. The freighting service that they could provide to Indigenous trading partners enabled the French to step into the role of middlemen themselves or, to be more precise, to eliminate Indigenous middlemen altogether. There would be Indigenous trading chiefs who approximated middlemen roles but none would ever attain the stature in the trade once held by the Wendat.

Another change in circumstances was the Crown’s reinvigorated interest in the colony. Louis XIV (born 1638, ruled 1643–1715) came to the throne as a child of five years but his first opportunity to take charge only came in 1661, when he was barely 23 years of age. The death of the chief minister, the gifted and well-connected Cardinal Jules Mazarin, provided Louis with a chance to take power from his mother, the regent. What looks outwardly like a break in the Richelieu-Mazarin legacy was, on closer inspection, a continuation. Louis inherited a system of governance that Mazarin had been building up for years, one that was more centralized and enabled to the Crown to exercise absolute authority. Louis XIV pushed the system farther down that path, took on the mantle of the “Sun King,” made it clear that he subscribed to belief in the divine right of kings (that is, that monarchs derive their power directly from God), and set about declawing the French nobility. Louis XIV’s reign had great consequences for New France: he remained in power for more than 72 years and thereby provided a degree of stability that had hitherto been lacking. Of course, no one in 1661 could know that the Sun King was going to enjoy such longevity. What New France could not mistake, however, was the king’s seriousness of purpose as regards the colonies.

The Royal Administration

In 1663 the era of private monopolies in the colonies came to an end and New France became a royal colony. Troops were sent out almost immediately to counter the Haudenosaunee threat and the men of the Carignan-Salières Regiment were given land and an opportunity to become part of the colonial elite. Immigration was stimulated, as was natural population increase by the recruitment and arrival of the filles du roi (the king’s daughters). Roughly 800 women (most of them young) were sent out from France at the Crown’s expense between 1663 and 1673. The plan was to marry them off to the men of the regiment and anyone else who might thereby be encouraged to settle down, raise a farm and a family, and become a permanent part of Canadien life. Another important category of recruit to the colony was the indentured servant or engagé. Almost exclusively a population made up of men in their early twenties, engagés signed on for three to five years of obedient service to a master in the colony. Often the party that owned the servant’s contract was a religious order. The Sulpicians of Montreal in particular made use of many engagés during the 17th century. The work of servants was hard, mostly thankless, and largely consisted of farm labour. For the most part, attempts at escape were punished publicly and physically. Engagés were too poor to marry and form households and were, in any event, prevented from doing so by law. Freed engagés, on the other hand, could do so, providing they had the necessary resources — which few did.

These population initiatives were mostly the responsibility of Louis’ new Ministre de la Marine, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683). As a royal province, Canada was now viewed by Versailles as more an extension of France than a remote colony. To that end Colbert launched projects that would tailor the embryonic colony into something much more like France, ideally without the institutions that most worried the king. For example, the clergy were to carry on playing important roles (some of which would be enhanced) but they were to defer to the king rather than to Rome. Mercantilism was to become less single-minded: the colonies would continue to serve the interests of the empire first and foremost, but opportunities for economic diversification and greater self-sufficiency would be explored. To that end, Colbert created a new official position in the colonies, one that would represent the Crown’s interests while promoting economic development.

The first occupant of the office of the intendant was Jean Talon (1626–1694). Appointed for two terms (1663–1668 and 1670–1672), Talon initiated bold and ambitious plans to improve the circumstances, potential, and viability of Canada at a time when the colony was economically and physically vulnerable. His strategy included building up agricultural output, establishing shipyards, and generally addressing the trade imbalance of New France by linking Canada with markets in the French West Indies. Very little of this came to pass but the population increased substantially under Talon and the possibility of a self-sufficient colony could now be seen in the distance. At the heart of this was the seigneury, a landholding system akin to French feudalism with distinctive North American modifications.

The Seigneurial System

The key elements of the seigneurial system include the personnel and their roles, the land-use pattern involved, and the ways in which the system integrated into the rest of the economy. Seigneurs occupied a position similar to that of the French nobility, both with regard to their peasantry and the king, to whom they had to swear an oath of loyalty. (Louis XIV was careful not to create a colonial aristocracy that might challenge his authority.) The seigneurs were granted large tracts of land along the river systems of the colonies, out of which they had to carve their own farm or domain. They had to provide common land and long, narrow strips of land stretching back from the riverfront for the censitaires or habitants. The Canadien equivalent of the French peasantry, the habitants were meant to defer to the seigneur, pay a fee or cens et rentes annually and a tithe to the church. The seigneur was to build a manor house on the domain, as well as a gristmill and a church. The seigneury, then, was to become the centre of population and community along the river. Unlike New England townships (as we shall see in Chapter 6), there were no villages to speak of in the seigneurial system, only a small number of large towns/cities. “Thus,” as one study concludes, “the importation of a European system of landholding led, under different geographical circumstances, to a radically modified dispersion of population and activities.”[1] Theoretically, the seigneurial system would produce a linear colony, one that hugged the riverbanks and pushed back the frontiers of forest at its rear.

In practice the seigneuries saw very little settlement before the 1730s. Many of the best seigneuries were granted from 1663 to 1700 but few were actually taken up and developed by the seigneurs. Seigneurs struggled to meet their expensive obligations and often found themselves with a noble-sounding title and a peasant-sized fortune. Habitants put a premium on cleared land and were not tied to the seigneury as fully as French peasants were in Europe: they could pack up and leave for a better piece of land if they so desired. Or, as many did, they could head west and north and join the fur trade. And, of course, fear of Haudenosaunee attacks put a further damper on seigneurial expansion until 1701. Nonetheless, the French had successfully established a core population on the land and Canada inched closer to self-sufficiency. Except for the Carignan-Salières Regiment, officials, and the filles du roi, almost all of the population growth in the century between the start of royal governance and the Conquest came from natural increase. In the whole of Canada’s colonial history from 1608 to 1760, it is reckoned that only 14,000 immigrants became part of the Canadien community.[2] By contrast Britain sent some 600,000 settlers to its colonies on the Atlantic seaboard in the same period.

The Compact Colony

From Talon on, intendants sought measures to reduce Canadien mobility and increase their commitment to the rural economy of the St. Lawrence Valley. As New France grew more sprawling, the more difficult it became to defend. And the more menfolk there were off trading along James Bay or skirting the Great Lakes in pursuit of furs, the fewer there were at home to build up food production and defend against British attacks. The intendants, however, were swimming against the current: Canadiens — from the habitants to the governors — saw the colony’s future as an expansive one of closely threaded alliances across an interior made up of Indigenous communities and a few French trading posts.

Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac (1622–1698), is probably the most outstanding example of this view. He was governor of the colony twice, from 1672 to 1682 and then from 1689, dying in office. Not only did he pursue policies that were at odds with those of Paris, he did so at the very time when Talon and Colbert were pulling in the opposite direction. Building forts further inland, encouraging René-Robert Cavalier de La Salle (1643–1687) to explore deep into the far west and down the Mississippi, and doing what he could to expand the fur trade were significant parts of Frontenac’s legacy, all of which was inconsistent with the goal of a “compact colony,” a Canada that was manageably small.

Montreal and the West

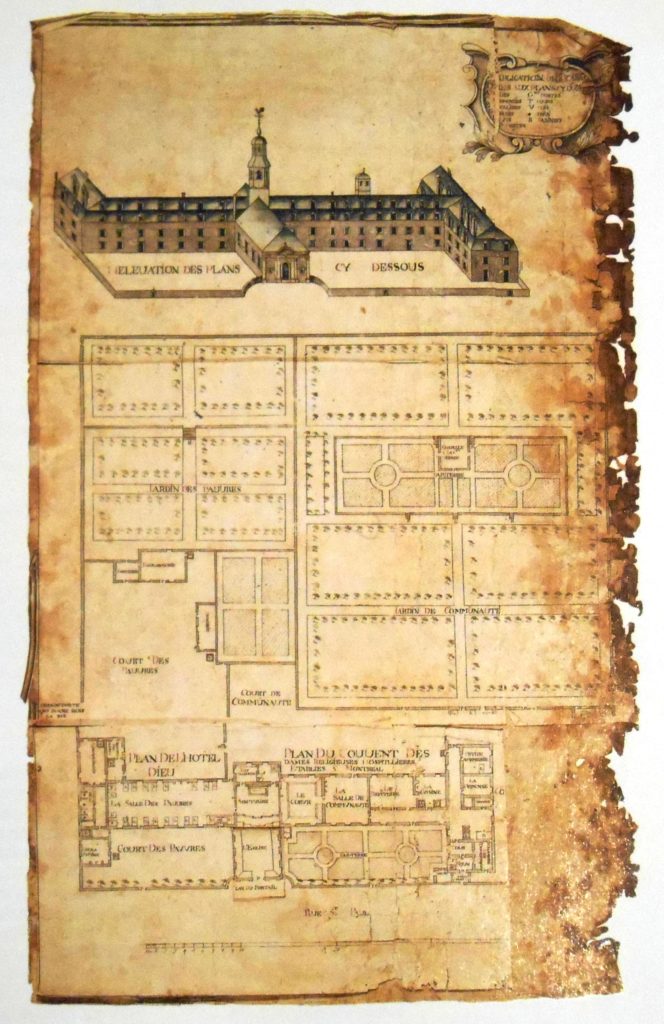

The history of Montreal in these years exemplifies some of the problems facing Canada and New France as a whole. Ville-Marie was established in 1642 as a religious outpost by the Société de Notre-Dame. This was a project in which Jeanne Mance (1606–1673), a member of the Ursuline order of nuns and the founder of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital, played a leading part. Montreal’s role quickly changed to fur-trade entrepôt. The population reached about 600 in 1685, many of whom were soldiers. The village was constantly under attack or seige or threat of these from the Haudenosaunee through the 17th century, and the destruction of Lachine in 1689 only a few kilometres away nearly doomed the village. From 1687 until the signing of the Great Peace of 1701 (discussed in Chapter 5), Montreal suffered from war with the Iroquois, a series of crop failures, and epidemics, which included a particularly virulent measles outbreak in 1687 that claimed 6% of the colonist population followed by another bout with smallpox in 1703. Small wonder that the opening of opportunities in the West was seized upon by many of its inhabitants: there were jobs to be had and possibly fortunes to be made in Detroit and the Pays d’en Haut.[3]

Some of the outcomes of Frontenac’s efforts should have been predictable. Longer supply lines in the fur trade required new systems of administration and investment. Larger, consolidated fur trade businesses began to emerge and demands for greater protection in the West were coming in from French traders and Indigenous allies alike. Rapid expansion into the West and South also brought an expanded supply of furs and, shortly thereafter, a glut on the European market. As one study points out, the fur trade did not respond well to market forces overseas: prices fell but the need for supplies continued to rise.[4] In part, responsibility for the deteriorating economy stemmed from a crisis of control. As one historian has memorably put it (her words having been translated from French into English), “Confusion reigned as market conditions continued to deteriorate. The interior monopoly was violated, and each [Canadien trader] struggled to save his own skin.”[5] Other historians have placed responsibility for the glut with Indigenous suppliers:

Instead of fewer furs coming in in response, however, there were more. This result … reflects a particular response of some native tribes. Many of them were nomadic, and accumulation of goods presented real difficulties. Extra pots, pans, or whatever, could be burdensome during the journeys from place to place. There was, in other words, a fixed number of goods desired by many [Indigenous] bands. The higher the price for their furs, the fewer the furs that would be necessary to supply their wants. In times of lower prices, however, more would be needed and more would be supplied.[6]

There were diplomatic considerations as well. Just because the market was bad that didn’t mean that New France could suddenly stop the cycle of gift-giving and commerce that undergirded alliances in the North and West. In this respect European and Indigenous markets worked at cross-purposes, and France was soon awash in furs while bills for colonial expenses piled up higher and higher. Exports tripled between 1685 and 1700.[7] Prices continued to fall after the Great Peace of 1701 and they stayed low for the duration of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714).

The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) concluded the war in North America, although it stuttered on for a few more months in Europe. It had the ironic effect of intensifying expansionist tendencies in Canada. Hudson Bay, Newfoundland, and Acadia were all handed over to the British. New France was reduced, though not severely, but in areas where the French had expended a great deal of effort. Rather than take this as a sign that the goal of a compact colony was more necessary than ever, it spurred new efforts. The loss of Hudson Bay certainly refocused French efforts along the Laurentian-Great Lakes routes and into the Pays d’en Haut. This situation arose in large part because France sought to use New France as a whole as a tool against Britain. By hemming in the 13 mainland British colonies, New France would frustrate British plans for continental dominance and, at the same time, limit the amount of support the British-American colonies could offer Britain in wars against France. For once, the imperial objectives of France were congruent with the more materialistic goals of the fur-trading colonists.

Exceptional Growth

After the Treaty of Utrecht, Canada improved on its uneven agricultural record and its population expanded rapidly. Women in the colony married younger than their counterparts in New England and France; they began producing children at a younger age and continued doing so for much of the rest of their lives. Widowhood was common (thanks to risks in the fur trade, intercolonial wars, and attacks by Indigenous opponents) and they remarried quickly. The effects were remarkable: by the middle of the 18th century, completed family size averaged between six and eight children, despite high infant mortality rates.[8] A high ratio of men to women in most of this period, combined with official encouragements to marry and form families and a strong cultural disinclination to reduce fertility in any way, shape, or form, yielded one of the most profoundly reproductive communities in the post-contact period.

Not only did the colony as a whole grow from about 10,000 in 1700 to nearly 50,000 people in 1760, the towns of Quebec and Montreal became somewhat more substantial. The former grew to about 8000 and the latter to 3500. The addition of the Fortress of Louisbourg and military reinforcements for the many fortifications that sprang up in the interior of the continent added still more “urban” people who were dependent on the farm produce of the Canadien seigneuries. For those habitants whose farmlands were sufficiently productive, these were good years and farm prices were healthy. For those living on newly cleared lands or in the tertiary “ranges” or rangs of the seigneuries, where soil was almost invariably worse and transportation more difficult, rising demand made little difference. For seigneurs — who received rents based on a share of output — the more mature farming areas were finally generating something like wealth.

Historians have maintained that the average censitaire in Canada was better off than his or her feudal counterpart in France. Some have argued, too, that they enjoyed greater liberties. By the same token, the seigneurs are widely thought to have been significantly less well off than even the more modest nobility in France, but were gaining on at least the lower aristocracy by mid-century. The impression remains, however, of a slow rate of change. Certainly there was no wave-after-wave of immigration as there was in the British colonies to the south, no land-hungry new arrivals whose presence alone could drive up the price of land. However impressive the natural increase of the Canadien population, the bottom line is this: the biological settler colony (as opposed to the territorial claim of New France) was vastly smaller than its neighbours.

The remainder of Canadien society presents something of a puzzle. Historians have long debated the importance of the merchant class in the colony. Insofar as their businesses remained mostly tied to the fur trade they weren’t significant agents for social and economic change before 1760. French merchants continued to exert a tremendous influence and controlled much of the import-export business from their homes in La Rochelle and Bordeaux. Economic historians Norrie and Owram have argued that what emerged by the mid-18th century, if not earlier, was a metropolitan-hinterland relationship of two steps: merchants in France capitalized and made the greatest profits from the traffic across the Atlantic, and they also had a hefty influence on the merchant class of Canada — often by dint of the fact that those colonial merchants were their employees/agents. The Canadien merchants, by extension, enjoyed a similar relationship with the interior of North America as the metropolis of a further hinterland.[9] Wealthy and influential merchants in the colony were nonetheless secondary to those in the home ports on the west coast of France and only some could translate their wealth into the status of a seigneur. This meant that upward social mobility was limited.

Canadien Society

This was a society with significant fracture lines and divisions. It wore the stamp of feudalism (however incomplete and modified to local circumstances) and had a strong military presence (with all the ranks and divisions that implies), a very large clerical presence with spiritual and everyday authority, a wealthy merchant class, and colonial managers who were regularly refreshed by new personnel from Louis XIV’s absolutist France. The poor and the common population were expected to recognize their superiors and show them deference. Indeed, no one was free from responsibilities of this kind: an insult inflicted on an official of rank or a senior cleric by an artisan or a creditor could result in a beating or a lawsuit. Cases seeking réparation d’injure verbale originated in all quarters of colonial French society and could involve men and women alike as both complainants and perpetrators. Canadiens and Canadiennes alike bridled at some of the social restraints imposed on them.[10] They were notoriously lax when it came to behaviour in church and records suggest that some appropriated titles — such as écuyer or esquire — to which they were not entitled. In a new country where reputations could be built, rebuilt, revised, and reduced, there was both sensitivity to status and a contrary willingness to undermine it. Gossip was an important regulating force when it came to domestic relations, probably more powerful than what little police force existed in the colony.[11]

This was, then, a rapidly growing Canadien society on top of which there was an cadre of metropolitan French authorities, some of whom wrestled mightily with the question of how far one should even want to control the colonials.

Key Takeaways

- The loss of Wendake (Huronia) forced changes on the colony of Canada.

- The introduction of royal administration placed a greater priority on establishing a more self-sufficient, Catholic, and compact colony along the St. Lawrence.

- A semi-feudal system of landownership and use was introduced that made Canada unique among European colonies in North America.

- The years between 1663 and 1712 saw an aggressive expansion of fur trade operations deep into the continent’s interior.

- The Treaty of Utrecht brought significant change to the shape and opportunities of New France.

Long descriptions

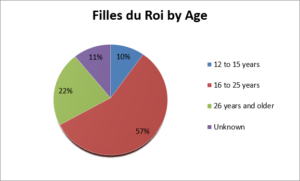

Figure 4.11 long description: Pie chart displaying the ages of the filles du roi between 1663 and 1673. The below table details the age ranges and their percentage shares.

| Age | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 12 to 15 years | 10% |

| 16 to 25 years | 57% |

| 26 years and older | 22% |

| Unknown | 11% |

Media Attributions

- Filles du Roi by Age © John Belshaw is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Plan de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal © 1695 by Gédéon de Catalogne is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kenneth Norrie and Doug Owram, A History of the Canadian Economy (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991), 74. ↵

- Roderic Beaujot and Don Kerr, Population Change in Canada, 2nd edition (Oxford: OUP, 2004), 24–25. ↵

- Louise Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth Century Montreal, trans. Liana Vardi (Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1992), 59–62. ↵

- Kenneth Norrie and Doug Owram, A History of the Canadian Economy (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991), 80–81. ↵

- Louise Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth Century Montreal, trans. Liana Vardi (Montreal and Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1992), 75. ↵

- Kenneth Norrie and Doug Owram, A History of the Canadian Economy (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991), 80. ↵

- Ibid., 80–81. ↵

- Roderic Beaujot and Don Kerr, Population Change in Canada, 2nd edition (Oxford: OUP, 2004), 25–26. ↵

- Ibid., 90–92. ↵

- Peter N. Moogk, “‘Thieving Buggers’ and ‘Stupid Sluts’: Insults and Popular Culture in New France, The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Series, Vol. XXXVI (October 1979): 524–547. ↵

- André Lachance and Sylvie Savoie, “Violence, Marriage, and Family Honour: Aspects of the Legal Regulation of Marriage in New France,” in Essays in the History of Canadian Law, Vol. V: Crime and Criminal Justice, eds. Jim Phillips, Tina Loo, and Susan Lewthwaite (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1994): 143–173. ↵

In English, known as “the king's daughters.” Between 1663 and about 1673, this cohort of women (mostly young and many orphans) was recruited by the Crown’s agents (mostly in Paris) for settlement in Canada. Their passage was paid for by the king, and they were provided with a dowry as an incentive to marriage.

Beginning in 1663, the administrative officer responsible for civil affairs in New France. The intendant’s portfolio included judicial affairs, infrastructure, military preparedness, addressing issues of corruption, and colonial finances. Notionally the most powerful figure in the colony, in practice, the intendant was often rivalled by the governor.

The seigneurial system in New France, and especially in the colony of Canada, sought to reproduce elements of the French feudal system. Although some of the seigneurs in Canada were nobles, most were military officers and members of the clergy. Rent values were based on rates set by the Crown, not on the scarcity of land or labour. Seigneurs had to provide their tenants (censitaires, habitants) with a gristmill (the use of which was essentially taxed), and the tenants provided an annual round of labour (corvée), which might involve road building or erecting a chapel.

Also known as “habitants,” the rent-paying tenants of the seigneurs. The rent is known as the cens.