Chapter 7. British North America at Peace and at War (1763–1818)

7.8 The War of 1812

The situation in Europe had changed drastically by the end of the 18th century. Inspired by the American Revolution and especially by its democratic ideals, the common people of France took up arms against their absolutist rulers. From 1789 to 1793, the French Revolution took the form of civil war and bitter infighting. France exported its violence in the French Revolutionary Wars that ran from 1792 with little in the way of breaks until the first years of the new century. An increasingly militarized state, France reverted in 1803 from republic to empire, with General Napoleon Bonaparte its new emperor. What followed was a near-global series of conflicts known collectively as the Napoleonic Wars.

Britain declared war in 1793 and one of the first consequences was a tightening of the Navigation Acts that closed off American access to the West Indies. The Americans responded with the Embargo Act (1807). The effect of these changes was to lift the Maritime economy once again. Baltic sources of lumber were soon closed off to Britain, which benefited the New Brunswick forest industry. On the whole, the Napoleonic Wars were very good to British North America’s economy. Conflict on land and sea in North America, however, put a damper on things. The first of these conflicts was a resumption of unfinished Indigenous business in the Ohio Valley.

Tecumseh’s War

The first Northwest Indian War (or Little Turtle’s War) followed hard on the heels of the American Revolution and lasted until the defeat of Indigenous forces by American soldiers at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Indigenous people thereafter ceded most of the Ohio Valley to the United States, moving farther west into the “Indian Territory” or “Indiana.” In the years that followed, many leaders of Indigenous tribes (that is, smaller units of organization) in the American “Northwest” tried to adapt to the newcomers’ ways. They signed treaties ceding lands in Ohio and Indiana to the United States, thus allowing for American settlers to move in and slowly expand American territory.

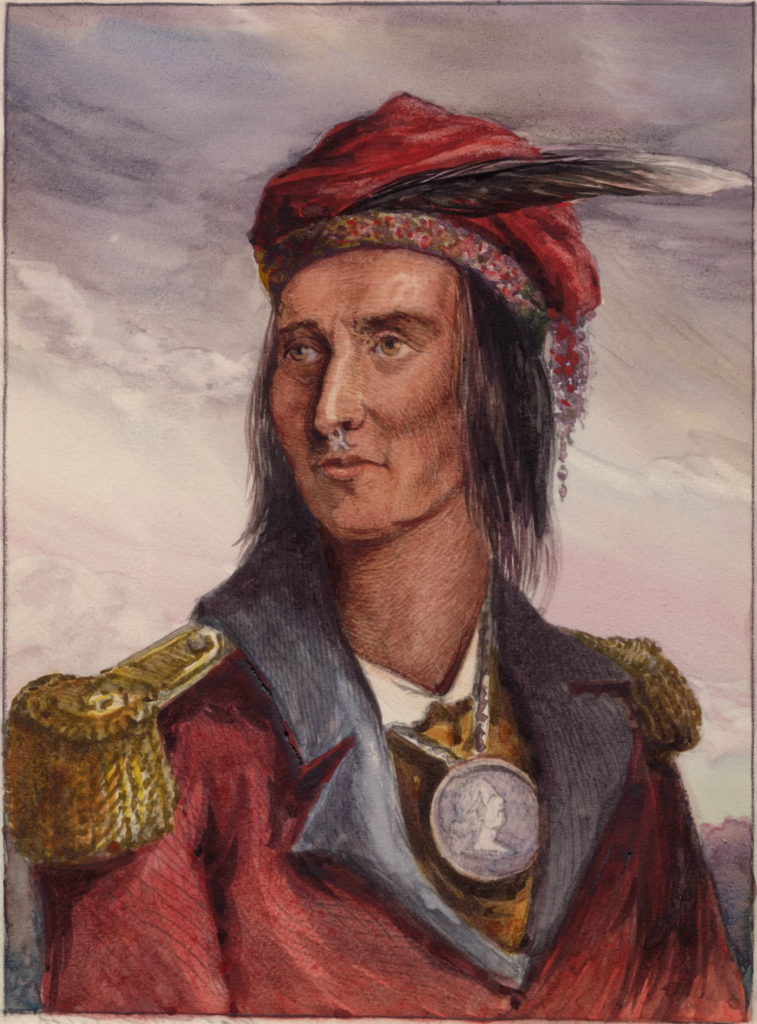

The chiefs who supported peace with the United States dominated the Amerindians of the area, such as the Shaawanwaki (Shawnee), Myaamiaki (Miami), and Lenape (Delaware), until 1805 when smallpox, influenza, and other illnesses swept through the Indigenous population. Among the dead was a Lenape leader, Buckongahelas, who had shepherded his tribe from Delaware to Indiana to escape American expansion years before. He and others like him did not trust the Americans and did not want contact with them, due in part to the history of violent conflict between the newcomers and the Lenape. With the death of Buckongahelas, new leaders rose from the tribes in the region, including two brothers from the Shaawanwaki: Tenskwatawa (1768–1836), also known as “the Prophet,” and his brother Tecumseh (1768–1813).

Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh both opposed American expansion into the region and what they saw as an unhealthy American influence on their people. Tenskwatawa had himself been a heavy drinker before having a transformative experience during an illness in 1805. From then on, he promoted a return to the old ways, calling upon Indigenous peoples of the Ohio and the Northwest to throw off Euro-American technologies, products, clothing styles, and cultural adaptations. This included rejecting Christianity. In this respect he was following in the footsteps of Neolin the Prophet. Tecumseh’s contribution was to argue for a unified, pan-Indigenous front that ignored the ancient distinctions between First Nations.

The leader of a large and extensive confederacy of mostly Algonquian-speaking peoples in the Ohio and lands to the west, Tecumseh’s message was one of common ownership of Indigenous land, as opposed to individual tribal treaties that signed away, piecemeal, the Ohio and then the rest of the continent. As the brothers rose to prominence and attracted followers, they drew American attention and contempt, which, in turn, created problems for pro-American Indigenous peoples who sought a peaceful co-existence with the settlers.

In 1808 the brothers and their followers moved westward and established Prophetstown on the Wabash River where it joins the Tippecanoe River, south of Lake Michigan. There, in November 1811, the Americans launched an attack on what had grown into a community of more than 3000 Indigenous people. Tecumseh was away on a recruiting mission and Tenskwatawa led his people to defeat. Tecumseh wasted no time in rebuilding the alliance, pointing to Prophetstown as an indication of what lay in store for Indigenous people who did not resist American incursions. Tecumseh sought out support from the British, which he secured. It was for this reason that the Americans accused the British of stirring up trouble on their western frontier.

The Second American War of Independence

Meanwhile, the British were harassing American shipping headed to France. The Royal Navy tried to starve France of imports and American shipping was an easy target. As well, the British were looking for British sailors who jumped ship to American vessels. There were plenty and they provided an excuse for the Royal Navy to seize American ships. An attempt to stop the American vessel Chesapeake in 1807 resulted in American casualties (including three dead) and the seizing of four alleged British deserters. The Chesapeake Affair pushed the so-called War Hawks in the U.S. Congress to agitate for war with Britain. It took nearly five years but they got a declaration of war on June 1, 1812. For the Americans this seemed like an enormous risk, one requiring a lot of bravado. But it wasn’t. Britain was not prepared to turn the full force of its military might on the United States; it was too busy in Europe fighting France. In fact, the British government had not wanted a war with the Americans at all. The actions of British admirals on the high seas reflected the needs of the Royal Navy, not the desires of the British government.

Nor did the rise in hostilities necessarily reflect the desires and interests of settlers on either side of the border. Trade across the frontier between British North America and the United States had, in fact, been stimulated by the Napoleonic conflict. Rising British demand for wheat could not be met by British North America alone, and American producers and shippers took advantage of the situation to export their grain through Canadian ports (as well as Halifax and Saint John). According to contemporaries, American grain shippers smuggled sledges over snow and ice to Montreal in winter and in summer, “gigantic rafts loaded with the produce of forest and farm and guarded by armed men were floated down the Lake Champlain route from Vermont north.”[1]

Upper Canadian settlers in the Niagara Escarpment included a great many Americans who had simply migrated westward and paid little heed to the border between the two countries. Likewise, Canadian exporters on the north side of Lakes Erie and Ontario shipped goods across the water to American ports. Families in exile since 1783 were in some instances reunited by these economic linkages before 1812. War, in these circumstances, was bad for business, even if one’s business was subsistence farming. Such concerns did not, of course, factor into the thinking of Britain or Washington.

The Americans could not attack Great Britain directly; an invasion of the British Isles was out of the question. To conduct the war, the Americans had to find British military targets at sea, in the form of the Royal Navy, and on land in North America, where the first obvious target was Canada. By 1812, some Americans believed that an invasion of Canada would trigger a Canadian revolt and help ensure an American victory, which might even bring the war to a quick end. They were wrong. The former American president Thomas Jefferson famously claimed that the “acquisition of Canada” would be a “mere matter of marching.” The war in the north went badly for the Americans at every stage.

Although the United States had declared war, Britain was better able to communicate to their colonists in North America about the outbreak of official hostilities. For this reason, the American garrison at Fort Michilimackinac was surprised when a British force arrived in July 1812 and demanded their surrender. The British force was small, consisting of the garrison from St. Joseph Island along with Indigenous warriors from several nations and some Canadians. The fort fell without a shot being fired. It was an inauspicious start for the Americans, and it sent a signal to Tecumseh that it was time to ready his troops for a coordinated attack on the Americans.

British relations with the Indigenous nations of the Great Lakes had improved after 1783. Rounds of gift-giving and quiet support for anyone who was harassing the Americans repaired Britain’s reputation in the Ohio and the Northwest. (The War Hawks were right in their suspicions in this regard.) Keeping the Americans off-balance in the West was undoubtedly in the best interests of the British and Canadians, although the settler society was hardly anti-American. Efforts to drum up support and voluntarism among the Upper Canadians was, as historian Jane Errington has demonstrated, largely a failure.[2]

The War in Canada

Tecumseh joined General Isaac Brock (1769–1812) near Detroit in an effort to jointly capture Detroit. Victory followed quickly on August 16, 1812, one that demonstrated a shared genius on the part of both commanders for psychological warfare. Through clever ploys and simple deception, they were able to convince the Americans that their forces were much larger than they actually were, and they both preyed on the Americans’ fear of an unbridled Indigenous attack. Brock had nothing but good things to say about Tecumseh. “A more sagacious or a more gallant Warrior does not I believe exist,” he wrote.[3] The fall of Detroit meant that the whole of the American Northwest was vulnerable. More Indigenous troops were emboldened to rise against the Americans and support the British, and they were all further encouraged by the subsequent fall of Fort Dearborn (Chicago) to a force of Potawatomi. Neither Tecumseh nor Brock would have long to savour these victories.

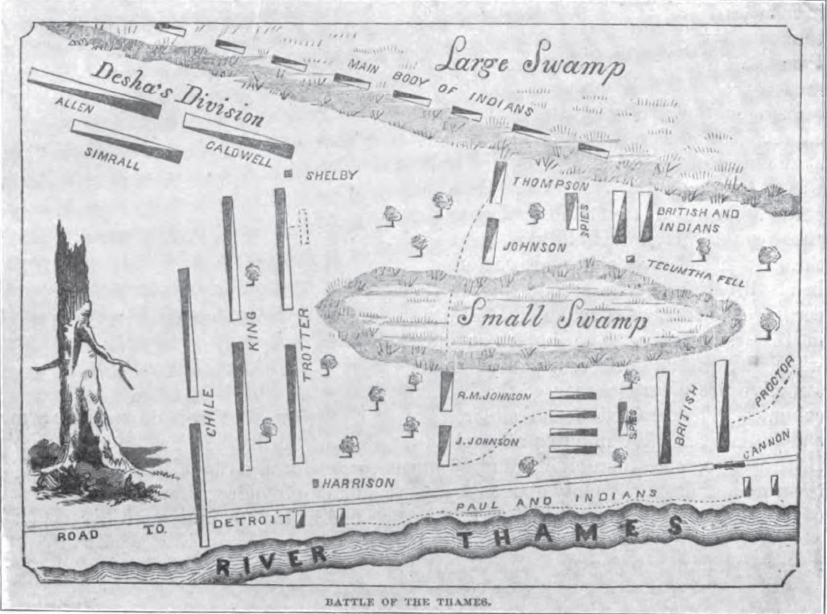

Tecumseh’s path took him into battles along the Lake Erie frontier. His forces were obliged to follow in the wake of Major General Henry Procter, a commander who lacked Brock’s resolve and imagination. Following setbacks on the lake and at Amherstburg, Procter led a retreat up the Valley of the Thames repeatedly refusing to take up offensive positions. Finally, at Moraviantown on October 5, 1813, Procter stopped running. His troops were, however, much depleted and demoralized. Against an American force three times that of the British-Indigenous-Canadian alliance, the outcome was almost certain. Tecumseh was one of the casualties of the battle. With his death the Confederacy and the dream of a unified Indigenous peoples’ homeland in the Great Lakes region perished as well. The Indigenous warriors from across the region dispersed and thereafter played only a minor and supporting role in the war.

Brock peeled off from the western frontier to defend the Niagara Peninsula in October 1812. An American assault on Queenston Heights failed badly with 1000 American soldiers captured, but Brock died leading an attempt to dislodge the Americans from the hilltop. In April 1813 the Americans launched a new cross-lake offensive, briefly capturing, burning, and looting York, then the colony’s capital. This was the first instance of destruction of public buildings for which the Americans would repeatedly pay a high price in 1815. The main focus of battle then shifted back to the Niagara Peninsula where Fort George fell to the Americans, but the Indigenous forces — alerted by Laura Secord, a local woman who had overheard American officers laying out their plans — were able to repel them at Beaver Dams on June 24, 1813. British regulars and Canadian militia played a larger role at Lundy’s Lane on July 25, but the outcome was largely inconclusive. This became a theme of naval battles on the Great Lakes in the year that followed.

The Americans were clearly exploring the pinch-points of Canada’s supply lines. Capturing the Niagara would have controlled the flow of supplies between Lake Erie and downstream Lake Ontario. Likewise the eastern end of Lake Ontario at Prescott became a target in an effort to cut off Upper Canadian troops from Montreal suppliers. The Battle of Ogdensburg, however, provided another victory for the British. The American garrison withdrew and commerce across the border resumed as though there was no war. Likewise the American attacks in late 1813 failed along the Champlain corridor. (Champlain Lake issues into Champlain River and then into the St. Lawrence and was a Haudenosaunee invasion route for centuries.) Battles at Chateauguay and Crysler’s Farm went well for the British forces. Importantly, Chateauguay was fought mostly by Canadien Voltigeurs, a volunteer regiment bolstered by promises of significant land grants at the end of the war, along with Kanien’kehá:ka from near Montreal.

Historians on Video

Cecilia Morgan (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto) has written a good deal on the creation of Canadian heroes in the 19th century. In this video she considers the elevation of Laura Secord a nationalist icon and an ideal of femininity. Here is a link to the transcript for a video about Laura Secord’s hero status in Canadian history [PDF].

Heading to a Draw

By 1813 American attacks on the Canadas ended. Abandoning their position around Fort George, the Americans decided to torch the town of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) and did so with the enthusiastic support of pro-American Canadians led by a member of the legislative assembly of Upper Canada, John Willcocks. The burning of Newark — and the subsequent deaths of civilians from exposure in metre-deep snow — led to the retributive assault on Lewiston, New York, which was only halted by Tuscarora warriors who interceded on behalf of American settlers. This moment stands out in the War of 1812 because it reflects the lack of the pan-Indigenous vision that Tecumseh had in mind: the troops stopped by the Tuscarora — the sixth of the expanded Six Nations Iroquois — included a large contingent of Kanien’kehá:ka warriors. Disunity among the Haudenosaunee clearly had not improved since 1783.

The Burning of Newark

Newark was Upper Canada’s original capital, but Governor Simcoe thought it was too vulnerable to attack and so moved the seat of government to York. He was prescient. The Americans were withdrawing from the Niagara Peninsula in the second week of December 1813. Their Canadian allies, led by John Willcocks, were exasperated at this turn of events and demanded that Newark pay a price for Upper Canada’s resistance. Willcocks and his volunteer regiment, overseen by the American troops, razed the town by fire. One eyewitness, a 16-year-old girl named Amelia Ryerse, subsequently reported on what she had observed: “When I looked up I saw the hillside and the fields as far as the eye could reach covered with American soldiers… My mother knew instinctively what they were going to do. She entreated the commanding officer to spare her property and said that she was a widow with a young family. He answered her civilly and respectfully and regretted that his orders were to burn… Very soon we saw a column of dark smoke rise from every building and what at early morn had been a prosperous homestead, at noon there were only smouldering ruins.”[4] Accounts claim that 149 homes were destroyed. The burning of Newark as well as the American raid on Port Dover in May 1814 (which was also burned) and the attempt to raze York (Toronto) contributed to the British decision to later torch the American capital.

The war dragged on for another year and a half, but the theatre of conflict was no longer along the British North American frontier. The Royal Navy’s attempts to press Britain’s advantage at sea on the east coast was intended in part to draw American troops away from Canadian targets. These new tactics, however, led only to gestures and stalemates, such as the burning of Washington and the shelling of Baltimore. British failure at New Orleans early in 1815 failed to dislodge the Americans from the Mississippi Valley holdings they had recently acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase.

Historians are divided over the outcome of the war, although everyone agrees that the Indigenous peoples of North America lost. Tecumseh’s Confederacy fell to pieces with his death, the Haudenosaunee remained divided, and even if the British and Americans could agree to provide a sacrosanct Indian territory in the midwest there was no one of Tecumseh’s stature left to pull it together. Continental domination, in any event, was within the grasp of the Americans and this was certainly confirmed by the outcome of the war. Indigenous populations across the northwest and the southeast were forcibly relocated to Kansas and Oklahoma, part of which is remembered as the “Trail of Tears.” The Wyandot — a coalition of Wendat (Huron) and Tionontati (Petun) — were among those removed to Kansas in the 1840s. British commitments to their Indigenous allies grew stale and a centuries-old partnership turned into something more like guardianship in the decade that was to follow.

Canada was a victor in that it did not lose any territory. Britain didn’t concede anything at the Treaty of Ghent, so it can be argued that the American failure to punish Britain for the Chesapeake counts as a British win. But the Americans had inflicted serious wounds on Canada, on British forces, on Indigenous alliances, and on the British Treasury. It was back to the status quo ante bellum after Ghent, but America was a changed nation. British North America’s survival was earned and deserved, but it lived with the consequences of 1812–1815 for many years to come.

Rush–Bagot, Republicanism, and British North American Identity

In 1817 the British and Americans signed the Rush–Bagot Treaty, which demilitarized the Great Lakes. Rather than a zone of conflict they became a zone of commerce. This worked splendidly for small and large merchants alike. Ideologically, however, it represented a significant change.

The elites of British North America were distinguished by a number of qualities, one of which was their Toryism. Loyalists from 1783 and their heirs were reinforced by a mythological legacy of 1812–1815 when, it was claimed, brave Canadian militiamen repelled American armies. This account purposely underplays the lack of interest (if not distaste) many Canadians felt toward fighting with their southern neighbours, but it served to legitimate the Chateau Clique in Lower Canada and the Family Compact in Upper Canada and the Maritime colonies. It was also a foil to brandish against those more republican-minded British North Americans who were outspoken in their admiration of American political institutions. To be a republican — rather than a Tory — was to climb into bed with the enemy to the south, not to mention the enemy in France. Toryism and privilege were safe for the time being.

No one was completely fooled by the more exaggerated claims of Tory myth-makers; there was no chance that a British North American militia could hold off an American assault without British support. British North Americans would continue, therefore, to thread their Western Hemispheric identity with one that involved Britain. Certainly the economy would continue to point in that direction as the colonies strove to survive and advance in the depression years after the Napoleonic Wars.

Historians on Video

The question of English-Canadian identity and its links to the War of 1812 are considered here by Jack Little (Simon Fraser University). Here is a link to the transcript of Jack Little’s introduction and video on English-Canadian identity in relation to the War of 1812 [PDF].

Key Takeaways

- The years between 1783 and 1815 were marked by almost continuous Indigenous resistance to American expansion into the Ohio Valley and what the Americans described as the “Northwest.”

- Americans suspected the British of stirring up and provisioning Indigenous resistance which, combined with British attacks on American shipping, contributed to a growing call in Washington for a “second War of Independence.”

- The initial stages of the War of 1812 went well for the British/Canadian/Indigenous forces but significant setbacks at Moraviantown and along the Niagara Escarpment resulted in an inconclusive outcome.

- The War of 1812 became a myth-building moment in the development of an Anglo-Canadian identity.

Video Attributions

- Dr. Cecilia Morgan Question 10 – Laura Secord. © 2015 by TRU Open Learning is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Dr. Jack Little Question 1 – Introduction. © 2015 by TRU Open Learning is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Dr. Jack Little Question 2 – The War of 1812 and the English-Canadian identity. © 2015 by TRU Open Learning is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Media Attributions

- Tecumseh © 1915 by Owen Staples is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Forces at the Battle of the Thames © unknown is licensed under a Public Domain license

- T. J. A. Le Goff, “The Agricultural Crisis in Lower Canada, 1802–12: A Review of a Controversy,” in Perspectives on Canadian Economic History, ed. Douglas McCalla (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman, 1987), 22. ↵

- E. Jane Errington, “Reluctant Warriors: British North Americans and the War of 1812,” in The Sixty Years’ War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814, eds. David Curtis Skaggs and Larry L. Nelson (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001), 325–336. ↵

- Herbert C. W. Goltz, “TECUMSEH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed August 30, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tecumseh_5E.html . ↵

- Quoted in Alistair Sweeney, Fire Along the Frontier: Great Battles of the War of 1812 (Toronto: Dundurn, 2012), 187. ↵

Federal legislation that was passed in the United States in 1807 to effectively close off all exports to foreign ports, in an attempt to force the British and French to respect American shipping. The objective was to starve the importing nations of American goods and thus oblige them to cease preying on American shipping. The act was repealed in 1809.

Conflict from 1785–1795. Part of an ongoing attempt by the Indigenous Northwestern Confederacy to insulate the Ohio Valley and what the Americans referred to as their Northwest Territory against American invasion. Also known as Little Turtle's War. Followed Pontiac's Rebellion and anticipated Tecumseh's War.

A British attempt during the Napoleonic Wars to reduce American shipping to France by capturing U.S. shipping vessels and impressing (forcing) sailors into the British Navy. In 1807, the USS Chesapeake, a warship, was bombarded and captured by the HMS Leopard; four sailors were seized and tried for desertion from the British Navy, one of whom was subsequently hanged. The Americans regarded this as an act of aggression, and the incident fomented war fever in some quarters.

American politicians mainly from the South and the West who were angered by British predations on American shipping out of their ports and harassment of American settlers and regiments by British-Indigenous armies. In 1812, their enthusiasm for war finally won out over New England's caution.

The sale of the Louisiana Territory by Napoleon to the United States in 1803. In 1800, Spain returned to France the territory it had ceded to Spain in 1762, which encompassed the western half of the Mississippi drainage (that is, from New Orleans to southern Alberta and Saskatchewan). Less than three years later, France decided to forgo attempts to rebuild New France and sold the territory to the United States.

Intended to end the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States. The treaty was agreed to in 1814, but not signed into law by the U.S. Senate until February 1815. The treaty restored the status quo ante bellum between British North America and the United States, which meant that Britain was removed from the American Northwest, leaving Indigenous peoples without an ally to help defend their interests.