Chapter 9. Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

9.4 The Cold War

The Cold War refers to the period of heightened tensions between the West (that is, the United States, Canada, Britain, France, and their allies) and the Soviet Union, lasting roughly from 1945 to 1991. Its origins can be traced to several sources but it rapidly became a war of postures and proxy wars between the two heavy-hitters, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Cold War was so named as it never featured direct military action between the two superpowers or their main allies. With the old “great powers” of Europe exhausted and battered by World War II, the United States (largely unscathed, the main creditor state in the world, and heavily industrialized) and the Soviet Union (badly beaten up but in a position to rebuild its defenses) emerged as the dominant powers. The addition of atomic bombs to their respective arsenals entitled them to a new title: superpowers.[1]

The Allies Fall Out

Having combined to defeat the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan), the Allies (principally, the USSR, the United States, and the United Kingdom) found themselves disagreeing on the shape of the postwar world. At the February 1945 Yalta Conference, the Allies could not reach a consensus on crucial questions like the occupation of Germany and whether Germany should be forced to pay reparations again. Given Russia’s historical experience of invasions from the West and the immense death toll it recorded during the war (estimated at 27 million), the Soviet Union sought to increase security by dominating the internal affairs of countries on which it bordered, and especially Germany. On the other hand, the United States sought military victory over Japan, the achievement of global American economic supremacy, and the creation of an intergovernmental body to promote international cooperation.

At the Potsdam Conference in July 1945, the Allies met to decide how to administer the defeated Nazi Germany. Serious differences emerged over the future development of Central and Eastern Europe. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima (6 August 1945) and Nagasaki (9 August 1945) were, in part, a calculated effort on the part of the American government to intimidate the Soviet Union, limiting Soviet influence in postwar Asia. The bombings served to fuel Soviet distrust of the United States and are regarded by some historians not only as the closing act of World War II, but as the opening salvo of the Cold War.

Canada lacked the profile of the Americans in these events but was up to its elbows in complicity. The Quebec Agreement was signed by United States President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) on 19 August 1943 in the old capital of New France. The agreement ensured British and American collaboration on what became known as the Manhattan Project; Canadian involvement was simply assumed. In 1944, Canadian scientists and technicians joined the multinational team in the United States, along with tons of uranium-bearing ore from the Northwest Territories. A Combined Policy Committee was established on which Canada was represented; it had oversight and coordination responsibilities regarding the atomic bombs. Canada was not, however, permitted to participate in the decision-making process as to when and where to deploy the new weapons.

Canada’s role in the Manhattan Project and the corollary — that there were Canadians who possessed sophisticated knowledge about how to manufacture the world’s first weapon of mass destruction — made Canada a target worth spying on. In Ottawa on 5 September 1945, a Ukrainian cypher clerk slipped out of the Soviet Embassy where he worked, carrying more than 100 top-secret documents detailing Russian espionage activities in Canada. Igor Gouzenko (1919-1982) disclosed the existence of a spy ring that included sleeper agents working under deep cover in Canada. The whole of the operation was geared towards uncovering nuclear secrets so that the Soviet Union could match the American arsenal at the earliest opportunity.

By February 1946, the public was aware of the Gouzenko Affair, which played out in the press and in Parliament. Fred Rose (1907-1983), the lone Communist Party MP in Ottawa, was implicated in the Gouzenko documents and was subsequently jailed for nearly five years. The late 1940s, then, saw the beginnings in Canada of a panic about spies that would push Canada further and faster away from her former Soviet ally and deeper into the orbit of Cold War America.

On 5 March 1946, Churchill gave a speech declaring that an Iron Curtain had descended across Europe. This metaphorical curtain divided East from West, leaving those nations behind it, as Churchill said, “subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.” To the Soviets, the speech seemed to intended to incite the West to war with the USSR, as it called for a broad western alliance against the Soviets.

In response to perceived Western aggression, in September 1947, the Soviets created Cominform (Communist Information Bureau) to enforce orthodoxy within the international communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet satellites through coordination of communist parties in the Eastern Bloc.[2]

Tensions between East and West continued to rise. In the spring of 1948, the focus shifted to Berlin. Germany and Berlin — along with Austria and its capital city, Vienna — had been divided into British, French, Soviet, and American sectors. The western Allies were on the verge of unifying their respective sectors of Germany as a whole — a development that the Russians were understandably unwilling to tolerate. In response, the Soviet Army initiated a blockade of Berlin, ensuring that food and fuel could not reach the American, French, and British zones in the capital. Unable to deliver goods by land or water through Russian-controlled Germany, the Western nations gambled on an airlift into the city.

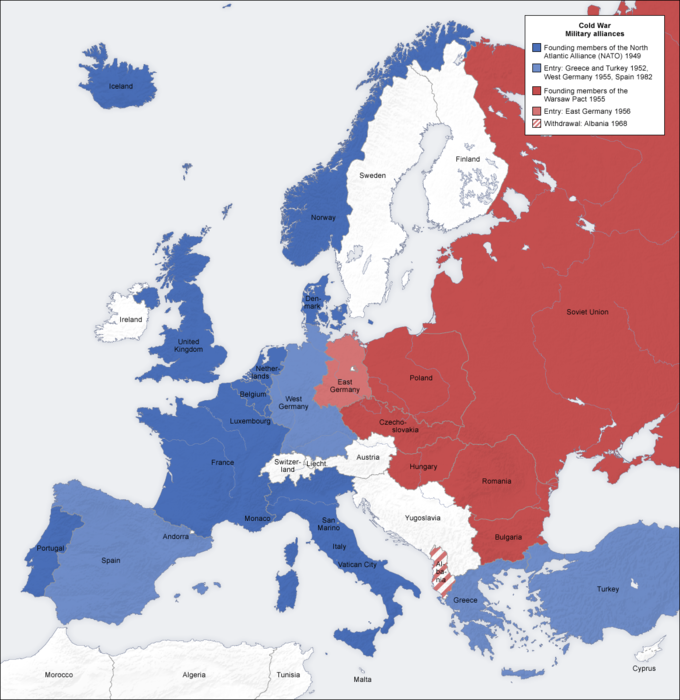

Just as these events were unfolding, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Britain, and Luxembourg entered into a new mutual defense treaty. The Berlin blockade and the vastly superior Soviet land forces in central Europe obliged the Treaty of Brussels group to look to a wider association that would include the United States, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Canada. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was the outcome: a mutual protection agreement under which an attack on one was to be regarded as an attack on all. For its first few years, NATO was not much more than a political association; the first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay (1887-1965), stated in 1949 that the organization’s goal was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” However, events quickly galvanized the member states, and an integrated military structure was built up in which Canada played a prominent role. [3]

By the late 1940s, the tone of global diplomacy and relations had changed dramatically from what it had been in 1939. When Britain declared war on Germany, the Canadian delay in responding was, in part, symbolic of the nation’s new relative autonomy; now, if Russia made a move on Luxembourg or Iceland, Canada would automatically be at war, regardless of what Britain might decide to do. Thee agreements reflected fears of a conventional attack involving aircraft, navies, and heavy armoured tank divisions. Then, in 1949, things became significantly more complicated and ominous.

On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. The United States’ monopoly on nuclear weaponry was over. A few months later, on 1 October 1949, Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung, 毛泽东, 1893-1976) announced the triumph of the Chinese Communists over their Nationalist foes in a civil war that had been raging since 1927. The Nationalist forces, under their leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣中正, 1887-1975), departed for Taiwan in December 1949. A few months later, an unresolved situation on the Korean peninsula would lead to the first hot moment in the Cold War. The Soviet Union had been granted control of the northern half of the Korean peninsula at the end of World War II, and the United States occupied the southern portion. The Soviets displayed little interest in extending their power into South Korea, and Stalin did not wish to risk confrontation with the United States over Korea. North Korea’s leaders, however, wished to reunify the peninsula under Communist rule. In April 1950, Stalin finally gave permission to North Korea’s leader Kim Il-sung (김일성, 1912-94) to invade South Korea, and provided the North Koreans with weapons and military advisors.

The Korean War

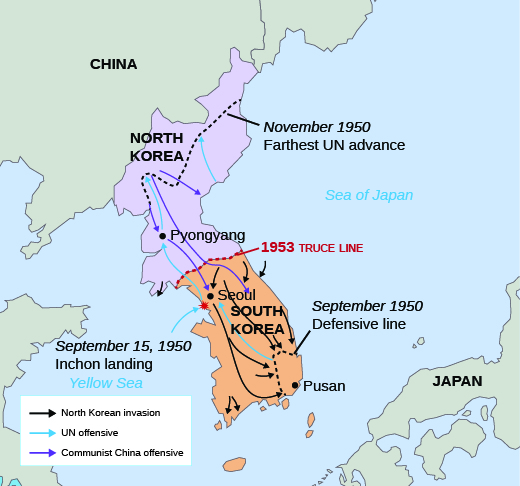

On 25 June 1950, troops of the North Korean People’s Democratic Army (PDA) crossed the 38th parallel, the border between North and South Korea. Within only a month, the PDA captured all but the southernmost region of the peninsula. The first major test of the West’s policy of containment in Asia had begun, for the domino theory held that a victory by North Korea might lead to further Communist expansion in Asia, in the virtual backyard of the West’s former enemy and newest ally in East Asia — Japan.

The United Nations (UN), which had been established in 1945, was quick to react. On 27 June 1950, the UN Security Council denounced North Korea’s actions and called upon UN members to help South Korea defeat the invading forces. As a permanent member of the Security Council, the Soviet Union could have vetoed the action, but it had boycotted UN meetings following the awarding of China’s seat on the Security Council to Taiwan instead of Mao’s People’s Republic of China (PRC). Spurred by the UN’s response, Canada’s Secretary of State for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson (1897-1972), proposed that Canada send troops under the UN flag, led by American military.

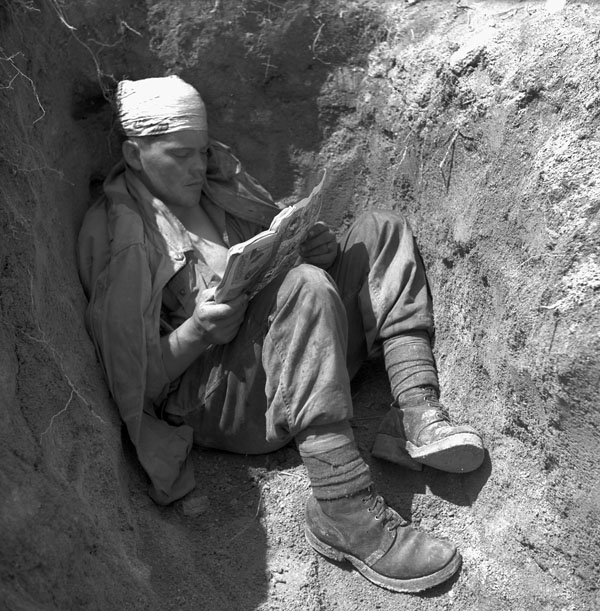

The Canadian troop commitment in the Korean War eventually reached nearly 27,000, and Canadians were active on sea, on the ground, and in the air — some of them flying combat jets, introduced in World War II but used only sparingly before Korea. Canadians performed many tasks but saw the most difficult fighting in three ground battles: Kapyong, Hill 355 (aka: Kowang-San), and Hill 187. Despite rapidly retaking not only the Republic of Korea but almost the whole of North Korea as well, the UN forces were confronted on the PRC’s border by hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops in the People’s Volunteer Army, who pushed the front back to the original dividing line, the 38th parallel, and forcing the American Eighth Army into a humiliating retreat. The status quo ante bellum was restored in 1953 — but not peace. Canadians stayed on duty in the PRC until 1957, monitoring — among other things — the Demilitarized Zone (aka: the DMZ). Both Koreas remain, technically, at war today. Five hundred and sixteen Canadians died in this conflict which, held against World War I or II, may not seem a great number. Nevertheless, this remains the third-largest loss of warriors experienced by Canada since Confederation.

Korea was a testing ground, too, for Canada’s approach to the Cold War. While the American administration under President Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) and Secretary of State Dean Acheson (1893-1971) was gambling on an Asian conflict that would cause the PRC to collapse in turmoil, the Canadians were much more committed to the objectives of the United Nations. Pearson was repeatedly at odds with Acheson, and the two foreign affairs offices developed a deep-seated mutual distrust and dislike. To take one example, Acheson claimed that a large number of Chinese and Korean prisoners of war (POWs) requested that they be allowed to remain in South Korea at the end of hostilities. The numbers were dubious, the whole idea was in conflict with the Geneva Convention, and Acheson’s transparent propaganda ploy blew up in his face when prisoners in the Koje-do Island POW camp demanded that they be returned to the North and to the PRC. Canadian troops were deployed to put down the ensuing riot, but without official Canadian consent. The effect was to entangle Canada in an affair that ran counter to its own foreign policy. As one study demonstrates, “Korea revealed the contradictions between the liberal-internationalist desire for the peaceful resolution of differences and the limitlessly aggressive logic of the anti-Communist Cold War crusade undertaken in Washington.”[4]

A Frosty Cold War

The Soviet Union’s involvement in Korea involved its new and impressive fleet of MiG-15 jet fighters, the PRC demonstrated its ability to put a massive and effective army into the field, and the UN showed that it could call on various member nations to contribute to the cause. It was also clear that the Americans had an agenda that was rather different from that of the UN, although the stopped well short of deploying atomic weapons to bring about a decisive victory. The Korean War, as well, served to establish a kind of Cold War protocol. Client states could host proxy wars that would stand in for the toe-to-toe conflict between the two superpowers.

Joseph Stalin’s (1878-1953) death did nothing to blunt fear of a Russian attack on Western Europe. By the mid-1950s, the West had come to terms with the need to re-arm West Germany (aka: the Federal Republic of Germany) because no other state had the population or industrial capacity to act as a physical barrier to Soviet aggression. A unified and re-armed West Germany was, of course, anathema to the Russians, who responded by bringing together their Eastern European tribute states (Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Bulgaria) into a mirror image of NATO: the Warsaw Pact. As in 1939, the northern hemisphere was dividing between liberal democracies and regimes characterized by the use of authoritarian power.

At home the Canadian response to the Cold War would take several forms. There were anti-communist purges in trade unions, the civil service, and elsewhere in Canada even before the McCarthyite witch hunts in the United States. Trade unions with a strong communist tradition, including waterfront workers’ organizations, were smashed under the leadership of Hal Banks (1909-1985), an American brought in to replace the left-leaning unions with the Seafarers’ International Union. As in Britain and other NATO countries, homosexuals were targeted (for reasons discussed in Section 12.7).

American fears of homegrown communist movements springing up in the Americas and in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia prompted interventions in various countries. In some instances, American involvement resulted in defeat of legitimate left-wing movements; in others, liberal democratic regimes were propped up. In Cuba, an unpopular regime faced local rebels who were supported by an American embargo. The government fell and was replaced by a regime headed by Fidel Castro (b. 1926), which proceeded to turn sharply left and align with the USSR rather than the United States. The Cold War was now in the Americas.

Polar and Polaris

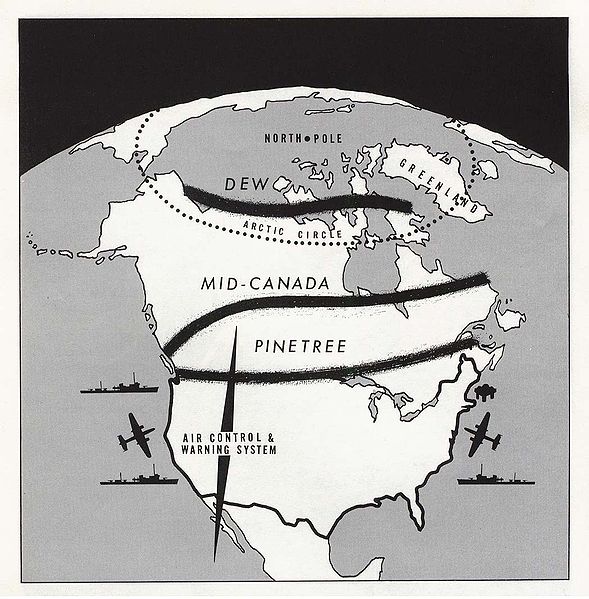

Technologies associated with warfare rapidly evolved after World War II. Canadian interest in jet-propulsion was led by A.V. Roe Canada (aka: AVRO), a British branch-plant in Malton, Ontario. Missile developments were also accelerating. Much of the advance made after 1945 was due to the availability of former German engineers who found themselves at the end of the war in either the Soviet or American spheres. In both the East and the West, intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) were being developed with a greater range and payload than conventional bomber aircraft. These delivery systems brought Soviet and American targets within striking distance, providing they crossed the Arctic and Canadian airspace. The 1971 post-apocalyptic novel by Ian Adams, The Trudeau Papers, described Canadians’ worst fears in these years, not of being targeted by the Russians but just being caught in between the two superpowers in a missile-slinging match. The spread of nuclear know-how and armaments to France (the so-called Force de frappe) and Britain (with its arsenal of submarine-launched Polaris missiles) did little to calm a growing sense that the world, including Canada, had no place to hide in the event of a nuclear war. The first material expression of these fears was the construction of the Pinetree Line beginning in 1946 and improved through the 1950s. This radar system, running from west to east from 50 to 54 degrees latitude, was introduced to detect an incoming Soviet bomber attack. In the 1950s, the Mid-Canada Line (or McGill Fence) was added further north in the face of advances in jet engines, which meant a faster target to intercept. The successor Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line followed in the late 1950s and through the 1970s as a response to the possibility of ICBM attacks. Strung across the Arctic Ocean from Alaska to Baffin Island, the Dew Line still stands as Canada’s single largest investment in infrastructure in the high Arctic.

Spy World

In 1963, British newspapers announced a scandalous liaison between Christine Keeler (a model and showgirl, b. 1942) and the Secretary of State for War, John Profumo (1915-2006). Keeler was also having a relationship with a Soviet military intelligence officer, Yevgeny Ivanov (1926-1994). The Profumo Affair, as it became known, set the tone for a similar scandal in Canada. In both, a femme fatale figured prominently as a sexual predator who could compromise national security. The Canadian press latched onto details as they came out of Ottawa, eager to sell a salacious affair to their readers.

Gerda Munsinger (1929-1998) was the main figure in this web of intrigue. She made several failed attempts to emigrate from postwar Germany under her birth-name (Hesler, Hessler, or Heseler, although she used several aliases). In 1955, she managed to elude immigration checks and arrived in Montreal, where she worked for a year as a maid and then as a sex worker and a hostess at Chez Paree, a Montreal nightclub. High-ranking government officials regularly frequented establishments like Chez Paree, and in no time Munsinger was having sexual relations with several of them. What’s more, she established regular liaisons with two of John Diefenbaker’s (1895-1979) cabinet ministers: Minister of Transport George Hees (1910-1996) and Associate Defence Minister Pierre Sévigny (1917-2004). Both the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the RCMP believed that Munsinger might pose a threat. Wiretaps on her apartment confirmed that she was having an affair with one or more cabinet ministers. Sévigny’s identity was allegedly confirmed by a thumping sound on the RCMP tapes that turned out to be his prosthetic leg coming off and hitting the floor. There was, however, no evidence of a security breach. Diefenbaker was advised of the situation in 1960; he instructed Sévigny to break off the relationship, Sévigny did so, and the matter was left there until 1966.

Spy cases continued to surface. The new Liberal government’s handling of one on the West Coast drew fire from the Progressive Conservative Official Opposition. Diefenbaker criticized the Minister of Justice, Lucien Cardin (1919-1988), of being lax in his pursuit of traitors; Cardin responded by invoking Diefenbaker’s involvement in the – to this point, secret – Munsinger case. Despite repeated attempts on Prime Minister Pearson’s part to contain the issue, Cardin disclosed what he knew to the press and was the first to draw the comparison with the Profumo Affair. There were, however, no new revelations of espionage, just marital infidelity on the part of Sévigny.

By this time, Munsinger had returned to Germany, where she remarried. The investigative journalism program, This Hour Has Seven Days[5], pursued the story and was abruptly cancelled thereafter by the CBC. The Munsinger Affair – which billed the central figure as a Cold War “Mata Hari” – perpetuated the notion of good men brought down by shady women working for enemy states. It was also something of a last gasp of the pre-sexual liberation era and says much about domestic, monogamous heterosexuality as not only a moral ideal but a matter of political and even national security as well.

Surviving the Cold War

Following the Suez Crisis in 1956 (see Sections 9.5 and 9.7), Canada engaged in a series of peacekeeping missions. These grew out of then-Foreign Affairs Secretary of State Lester Pearson’s idea of a UN observer force to calm relations between Egypt, Israel, France, and England. In the decade that followed, Canadian troops would be sent to Lebanon, Congo, West New Guinea, Yemen, Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, and along the India-Pakistan border — sometimes as observers, sometimes as trainers, sometimes as a barrier between opponents still snarling at one another despite a ceasefire, sometimes all these things at once. Eleven more missions would follow in the years before the end of the Cold War. While some of these missions involved client states of the West and East or their respective partisans, mostly they could be defined as events associated with decolonization. This was the case in the Congo (as Belgium made an undignified exit), West New Guinea (where conflict arose between colonialist Netherlands and newly independent Indonesia), and also in the long-running dispute between India and Pakistan in the generation following their independence from Britain. The Cypriot Mission — which began in 1964 and shows few signs of abating — also came on the heels of independence from Britain, followed by Greek and Turkish attempts to lay claim to what had been a Crown Colony. What is striking in these years is the extent to which these Cold-War–era conflicts were more fundamentally about 19th century imperialism than postwar superpower spheres of influence. This was not the case in Cuba.

The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 deepened Canadian fears of a nuclear war between Russia and the United States. The long-range missiles that the Soviet Union proposed to deploy on Cuba would certainly reach major Canadian population centres if they were ever launched. The Americans were insistent that the Soviets abort the project and, for the better part of two weeks, Washington and Moscow (which was, itself, affronted by the forward deployment of American missiles in Turkey) stared into the abyss.

Diefenbaker’s government offered support to the American government led by President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963), but not unconditionally. Diefenbaker preferred the idea of a UN-led intervention, something that got no traction whatsoever in Washington, DC. This tepid response led to heightened tensions between Canada and the United States. The crisis overall contributed to Canadian fears that the Americans would, by their own miscalculated actions, precipitate a nuclear holocaust. The Liberal Prime Ministers Pearson and Pierre Trudeau would follow Diefenbaker’s lead and were publicly critical of American foreign policy. (Joe Clark’s government was in office only briefly but evinced a more cooperative position generally.) After 20 years of sanctions, Ottawa opened discussions with China in 1968 and diplomatic recognition of the PRC in 1970. Canada (along with Mexico) did not sever diplomatic ties with Cuba, and Trudeau was the first Western leader to pay a visit to Havana. In 1972, Cold War drama played out on ice in the Canada-USSR Hockey Series (aka: the Summit Series); while the overarching narrative was West versus East, capitalism versus communism, the event generated in Canada considerable respect for the Soviet players, their coaches, and their fans, and thus put at least a small dent in the Iron Curtain. More formally, in 1976, Trudeau travelled to Cuba to meet with Castro. This was in keeping with Trudeau’s own foreign affairs perspective, and it was also in sync with the emerging American philosophy of détente. Nonetheless, growing American involvement in Cold War client-state wars from Vietnam through Africa and Latin America led to growing anti-American feeling among the Canadian public and that was reflected in Ottawa’s foreign policies.

The tenor of Cold War relations between Canada and the United States would continue to be mostly critical until Trudeau’s Liberal government was replaced in 1984 by Brian Mulroney (b. 1939) and a Conservative majority. Mulroney’s campaign to improve relations with the Americans led to a close personal relationship with United States President and arch–Cold-Warrior Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) and, eventually, to a free trade agreement between the two countries (discussed in Section 9.12). The dying years of the Cold War, then, would see Canada’s position vis-à-vis the Soviet Bloc harden into something that more closely resembled the American view.

Key Points

- The Cold War began at the end of World War II and persisted through the 1980s. It represents a polarization of global forces into two camps: America and its allies (represented by NATO and sometimes the UN) and the Soviet Union with its supporters (represented by the Warsaw Pact and sometimes China).

- Canada’s entry into the Cold War came with the disclosure in 1946 of a spy ring led by Igor Gouzenko.

- Involvement in NATO and support for the UN led Canada to be an active participant in the Korean War in 1949.

- In 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, and the age of superpowers was launched.

- Canadian defence strategies in the Cold War changed as Canada aligned more with the United States and prepared for a missile assault across the Arctic. Ottawa also launched an anti-fifth–column strategy to reduce the threat of homegrown communists.

- Involvement in peacekeeping missions began in this period as an attempt to find diplomatic solutions became a Canadian priority, in contrast with the American strategy of containment.

Long Descriptions

Figure 9.16 long description: Cover of The Globe and Mail from February 18, 1946. The headline is “FBI Joins Ottawa Spy Hunt: Investigation Now Focused on Munitions Department.” Subheadings in the article include “Documents Included In Roundup,” “Investigation of Spy Ring In Canada Started Last Fall,” and “Secrecy Is Maintained By Officials.” Beside this text are photos of a smiling man and woman. [Return to Figure 9.16]

Figure 9.19 long description: Map depicting Cold War military alliances. There are five different factions depicted:

- Founding members of the North Atlantic Alliance (NATO) in 1949. This includes Portugal, France, Monaco, Luxembourg, Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark, United Kingdom, Iceland, Norway, Italy, San Marino, and Vatican City.

- Entry into NATO: Greece and Turkey (1952), West Germany (1955), Spain (1962).

- Founding members of the Warsaw Pact in 1955. This includes the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

- Entry into the Warsaw Pact: East Germany (1956).

- Withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact: Albania (1968).

Media Attributions

- Private G.U.I. Lambert, B2nd Battalion Royal 22E Regiment, reads comic book in slit trench, Korea, 28 May, 1951 © Paul E. Tomelin, Canada Dept. of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada (PA-128806) Copyright Government of Canada. No restrictions on use.

- First load of uranium concentrate flown from Great Bear Lake to Fort McMurray, 1935 © W.L. Brintnell, Library and Archives Canada (PA-102850) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- FBI Joins Ottawa Spy Hunt, 1946 © The Globe and Mail is licensed under a Public Domain license

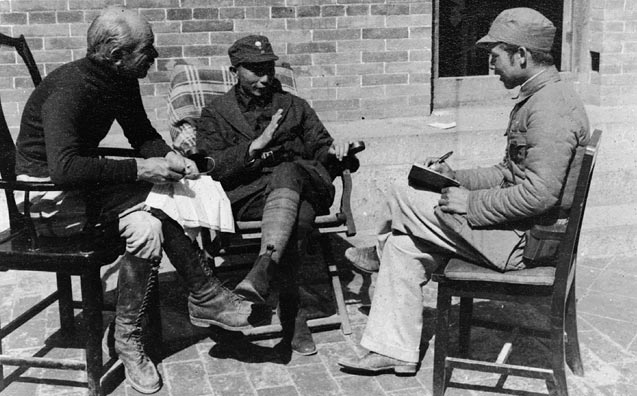

- Meeting between Dr. Norman Bethune (left) and Nieh Jung-Chen (centre), Commander-in-Chief of the Chin-Ch’a-Chi Border Region © Library and Archives Canada (PA-114787) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Korean War, 1950–1953 © OpenStax. Download for free here is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Cold war Europe military alliances map © Wikipedia user San Jose is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- DEW Line, 1960 © United States Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Two Canadian soldiers scan the Egypt-Israel frontier during a desert patrol, 1962 © Canada Dept of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada (PA-122737) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Boundless. “Origins of the Cold War”. Boundless U.S. History. Boundless, 21 Jul. 2015, accessed 17 Dec. 2015 from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/the-cold-war/ ↵

- Boundless. “Origins of the Cold War”. Boundless U.S. History. Boundless, 21 Jul. 2015, accessed 17 Dec. 2015 from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/the-cold-war/ ↵

- Boundless. “North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)”. Boundless U.S. History. Boundless, 21 Jul. 2015, accessed 17 Dec. 2015 from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-ushistory/chapter/the-cold-war/ ↵

- Reg Whitaker and Gary Marcuse, Cold War Canada: The Making of a National Insecurity State, 1945-1957 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 396-401. ↵

- From which the comedy troupe, This Hour Has 22 Minutes, derives its name and news-show format. ↵

The prolonged period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, based on ideological conflicts and competition for military, economic, social, and technological superiority, and marked by surveillance and espionage, political assassinations, an arms race, attempts to secure alliances with developing nations, and proxy wars.

Cold war era conflicts conducted by third party countries in which the United States and the Soviet Union had a stake, rather than a direct conflict between the two superpowers.

Espionage agents who are deeply embedded in the host community and dormant, awaiting activation.

Post-WWII espionage case involving a clerk at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa who disclosed the existence of a spy ring in Canada.

A term coined by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to refer to portions of Eastern Europe that the Soviet Union had incorporated into its sphere of influence and that no longer were free to manage their own affairs.

The alliance of pro-Soviet (or USSR-dominated) countries in Eastern Europe in the post-WWII era, consisting of Poland, East Germany, Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and, more loosely, Albania. Yugoslavia, another communist-dominated country, regularly declared itself separate from the Eastern Bloc; formalized in the mutual security agreement, the Warsaw Pact, 1955.

The American policy that sought to limit the expansion of Communism abroad.

The theory that if Communism made inroads in one nation, surrounding nations would also succumb one by one, like a chain of dominos toppling one another.

An international body established in 1942; originally was the rough equivalent of the Allied Nations in the Second World War; expanded to a post-war role in 1945 as an intergovernmental assembly and series of agencies tasked with reducing international tensions and addressing international social and economic crises.

A war that began in 1950 and ended inconclusively in Armistice in 1953; this was Canada's first Cold War era military engagement, and it involved significant casualties.

1864, 1906, 1929, 1949; a succession of international agreements on the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs) and civilians.

Colloquial term used to describe security campaigns conducted in capitalist democracies during the Cold War which targeted, mainly, communists but also homosexuals and any other group regarded as potential seditious.

Cold War-era surface-to-air missiles with no less than a 5,000 km range; typically nuclear-tipped.

The 1956 invasion of Egypt by Israel, followed by France and Britain with the objective of seizing the Suez Canal. The failure of England and France to inform their former Allies -- especially the United States -- of their plans led to a rift between Britain and the USA in particular. Canada's response, led by Lester Pearson, was to propose a large multi-national peacekeeping force in the region.

The relaxation of tensions and improvement of relations between the West and the East in the Cold War during the 1970s.