Chapter 9. Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

9.8 Trudeau I

The election in 2015 of a government led by Justin Trudeau (b. 1971) has sharpened the public’s memory of his father, Pierre Elliot Trudeau (1919-2000). Raised in a well-to-do household in Outremont, Quebec, Pierre Trudeau’s roots in Canada wind back to the 1650s on one side, with Scottish-French ancestors on the other. Biographers have observed this apparent bridging of the two solitudes but everything else about Pierre Trudeau’s early life suggests a strong and very conventional allegiance to things Canadien. He was educated at an elite Jesuit school and was imbued with a strong sense of French-Canadian nationalism. As a young man, he was old enough to serve in the Second World War but, like most of his generation in Quebec, he opposed conscription. He completed a law degree at the Université de Montréal, then studied at Harvard University and the London School of Economics. Although he failed to complete his doctorate, he was regarded in Montreal as an intellectual. Before he was 30 years old, he had established a reputation as a dissident writer and journalist with a strong pro-labour orientation. Personal wealth and extensive connections allowed him opportunities in Ottawa (where he worked as an economic policy advisor to St. Laurent) and the wherewithal to establish Cité Libre, a publication that regularly critiqued the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis and gave voice to the early stages of the Quiet Revolution. Duplessis, it is alleged, responded by ensuring that Trudeau could not find work in Quebec universities. Certainly it was not until after Duplessis’ death that Trudeau was taken on by the Université de Montréal as a law professor. It was there that Lester Pearson approached him about a career in politics.

The Three Wise Men

In his mid-40s, Trudeau still had close ties with labour organizations and was favourably disposed toward social democrats within and without the CCF/NDP. But he regarded their ability to achieve change as very limited and was persuaded to join the Liberal Party in 1965 as part of a trio of Quebec recruits known as the Three Wise Men (or les trois colombes): Trudeau, Gérard Pelletier (1919-1997), who was another founder/writer for Cité Libre, and Jean Marchand (1918-1988), who was a trade union organizer and activist. Marchand was, in many respects, the high-profile member of the three, and he was quickly given a prominent role in the Pearson government. Trudeau was made Parliamentary Secretary to Pearson, a kind of personal advisor, and he quickly acquired an understanding of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). Soon thereafter he was made Minister of Justice, despite having only just joined the Liberal Party and having never before held elected office.

In 1967, the Liberal Party began the process of finding a successor to Pearson through a leadership convention. Marchand was favoured to run as the French-Canadian candidate but he declined, claiming (correctly) that his English was insufficient.[1] Trudeau was persuaded to run but his candidacy was divisive. As Justice Minister he had made divorce easier to obtain, he had permissive attitudes toward abortion, and was regarded by many in the Party as radical on other social issues. It took four ballots for Trudeau to narrowly win with only 51% of the vote.

The Leadership Convention received unprecedented media attention and served as a launchpad for the federal election the same year. Echoing the appeal of “British Invasion” bands of the decade, public fascination with Trudeau was promoted as Trudeaumania. Although he was nearly 50 years old, Trudeau was seen as youthful and virile — the personification of a generation’s desire to shake up establishment values. He arrived on the political scene at roughly the same time that the Baby Boomers born in 1945-47 became voters and, raised on a cultural diet of television news and the sexual revolution, they regarded Trudeau as one of their own. The contrast with his two opponents — Conservative Party leader Robert Stanfield (1914-2003), heir to a textile manufacturing fortune, a Red Tory, and a former Nova Scotian Premier, and Tommy Douglas, leader of the New Democratic Party, a former Premier of Saskatchewan, and the author of the nation’s first healthcare legislation — was sharp. Stanfield and Douglas (both thoughtful and arguably no less intellectually gifted than Trudeau) had age and experience on their side, but they also had age and experience working against them. Trudeau — still something of a novice in politics — was suavely articulate in both languages, spoke out against radical nationalists in Quebec, and brought little baggage with him. The results were a convincing majority for the Trudeau administration in 1968.

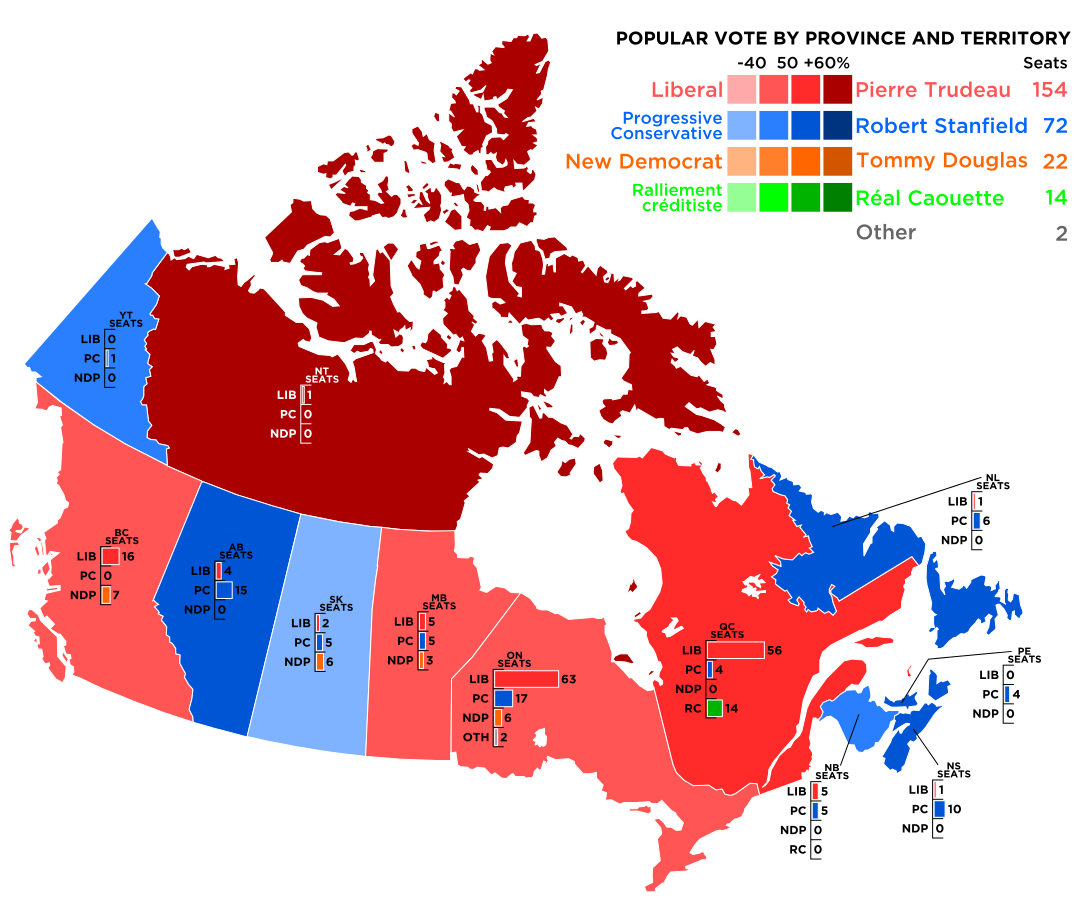

In later years, Trudeau would be regarded as nationally divisive. If we look at the 1968 results, it is clear that some of the fracture lines were already present. Although the Liberals did well in central Canada and British Columbia, Manitoba was a wash, Stanfield’s Conservatives were runaway winners in Alberta and Atlantic Canada, and the NDP came out on top (narrowly) in Douglas’ home province. The precariousness of Trudeaumania would become clear only four years later.

Trudeau’s first years in office were marked by controversial policies and events. The 1968 election took place against a backdrop of increasingly violent separatist protest in Quebec. Indeed, Trudeau’s unwillingness to leave a viewing platform at the pre-election Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day parade, despite being heckled and bombarded with bottles and stones, was seen by many as a demonstration of the toughness needed to stand up against separatism. It is even regarded by some historians as a turning point in the election campaign. But it presaged the principal difficulty he would face over the next 15 years: the challenge of Quebec’s historic dissatisfaction with Confederation.

Key Points

- Pierre Trudeau’s arrival on the national political stage followed decades of activism in support of organized labour and his writing as a dissident intellectual in Duplessis’ Quebec.

- Trudeau was recruited by the Pearson Liberals as part of a package aimed at reviving party fortunes in Quebec.

- In a brief career as Minister of Justice, Trudeau was able to introduce new laws and more liberal attitudes on social issues.

- Despite being in his late 40s, Trudeau was regarded by the electorate as a fresh personality who could be tough on separatism.

Long Descriptions

Figure 9.37 long description: Map depicting the results of the 1968 Canadian federal election. The Liberal Party (Pierre Trudeau) won 154 seats, the Progressive Conservative Party (Robert Stanfield) won 72 seats, the New Democrat Party (Tommy Douglas) won 22 seats, and the Ralliement créditiste party (Réal Caouette) won 14 seats. Two seats went to other parties. Broken down by province or territory:

- British Columbia: 16 seats for the Liberals and 7 for the New Democrats (NDP) (69.6% Liberal)

- Alberta: 4 seats for the Liberals, 15 for the Progressive Conservatives (78.9% Progressive Conservative)

- Saskatchewan: 2 for the Liberals, 5 for the Progressive Conservatives, 6 for the NDP (38.5% Progressive Conservative)

- Manitoba: 5 for the Liberals, 5 for the Progressive Conservatives, 3 for the NDP (38.4% Liberal)

- Ontario: 63 for the Liberals, 17 for the Progressive Conservatives, 6 for the NDP, and 2 for other (71.6% Liberal)

- Quebec: 56 for the Liberals, 4 for the Progressive Conservatives, and 14 for the Ralliement créditiste (75.7% Liberal)

- Newfoundland: 1 for the Liberals, 6 for the Progressive Conservatives (85.7% Progressive Conservative)

- New Brunswick: 5 for the Liberals, 5 for the Progressive Conservatives (50% Progressive Conservative)

- Nova Scotia: 1 for the Liberals, 10 for the Progressive Conservatives (90.9% Progressive Conservative)

- Prince Edward Island: 4 for the Progressive Conservatives (100% Progressive Conservative)

- Yukon Territory: 1 for the Progressive Conservatives (100% Progressive Conservative)

- Northwest Territories: 1 for the Liberals (100% Liberal)

Media Attributions

- P.E. Trudeau at the Liberal Leadership Convention, Ottawa, Ont. © Duncan Cameron, Library and Archives Canada (PA-111213). Copyright assigned to Library and Archives Canada by copyright owner Duncan Cameron. No restrictions on use.

- John Lennon and Yoko Ono with Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau © D. I. Cameron, Library and Archives Canada (PA-110805). Copyright Library and Archives Canada. No restrictions on use.

- Canada 1968 Federal Election © Wikipedia user Lokal_Profil is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- To be fair, this sort of concern did not impact English-Canadian leaders the same way until the late 20th century. “Diefenbaker-French” was a term widely used to describe a garbled version that was incomprehensible to Francophones but strangely recognizable to Anglophones. ↵

A period of rapid and consequential change in the character of Quebec politics and society beginning in the late 1950s.

Les trois colombes, a term used mainly by commentators to describe the trio of Jean Marchand, Gerard Pelletier, and Pierre Trudeau when they were recruited to the federal Liberal Party in the 1960s.

Also the Office of the Prime Minister or the PMO; the centre of political decision making in the Parliamentary system, consisting of the Prime Minister and her/his chief political advisors; in Ottawa, located in the Langevin Block on Parliament Hill.

Term used principally by journalists to describe public and media fascination with Pierre Trudeau in the course of the 1968 Liberal leadership convention and then the general election; alludes to the phenomenon of Beatlemania, associated with the British Invasion.