Chapter 9. Cold War Canada, 1945-1991

9.1 Introduction

The period from 1945 to 1991 was one of dramatic technological and social change. Much of the material texture of life had so changed from the pre-war era that it is difficult to imagine that the two eras were somehow related. The shape of cities, the availability of affordable clothes, the appearance of new household appliances, the explosion of automobilism, and crucial developments in the area of media and entertainment all created a shockingly new version of the modern world.

While there were massive watersheds, however, there was also continuity. Of these, William Lyon Mackenzie King was only the most obvious. Even after King’s retirement from politics, his immediate successors were drawn from the pool of politicians who were born in the late 19th century and could remember World War I almost as clearly as World War II. That connection to the Edwardian — let alone the Victorian — era was, however, receding behind decades of social and economic trauma.

Demographically, the Canada that was emerging after 1945 was distinct from what went before. The young couples who were rushing to marry and restore what they regarded as “normalcy” after the Depression and World War II were mostly products of the interwar years and were glad to put all that behind. Their children — that generation born as early as the late 1930s but especially after VE Day and in rising numbers to the late 1950s — were the baby boomers whose very existence transformed the economy. Rising fertility rates led to investment in maternity wards; rising infant numbers to more children’s clothes and toy factories; rising child numbers to more schools and skating rinks. The arrival of a generation of adolescents called for vastly more high schools and new ideas about consumerism and music. And by the time the baby boomers were in their late teens and twenties, by the time they were entering universities, the workforce, and the electorate, they were a democratic tidal wave. This was a generation that was welcomed in the context of Canadians’ appetite for greater normalcy in domestic relations. They were also an asset in the new consumer-led economy. The main legacy of the baby boomers, however, would be structural challenges to those underlying postwar values.

There was evidence of dissatisfaction, new ideas, and experiments in many aspects of Canadian life. Chapter 10 considers elements of modernity as it evolved from the early 20th century through the postwar years. This chapter, however, focuses more specifically on the links between social, economic, and political changes that took place in the Cold War years. It begins with a survey of the events leading to the amalgamation of the two Dominions and a consideration of the experience of the North as the Cold War era took root.

It has been customary to think of the 1960s as a turning point that toppled old social and cultural values, and there are elements of truth to that. What an overview of these years most clearly demonstrates, however, is the continuing struggle between ideals like the liberal-democratic order, the interventionist state, the rights of the individual versus collective identities, and the continuing vigour of conservative social and economic philosophies. Many of these themes were picked up internationally, especially in the English-speaking world. The internationalization of media was a critical element in that synchronizing process as was the internationalization of markets. In Canada, discussions over what constituted “progress” were the backdrop for a return to the pre-WWI debate over what constituted the idea of “Canada.” As it became increasingly clear that Quebec’s visions of the future of Canada were different from those of English Canada, the confederation skated close to the edge of disintegration from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Every debate about family, prosperity, unemployment, sexuality, entertainment, and technological developments in these years took place in a unique historical context: the Cold War. After 1953 especially, the fear of mutually assured destruction (MAD) amplified fears in the Western world of the threat posed to its particular social and economic world by the Soviet Union and the expanding reach of communist regimes. A polarized world populated every conversation. What happened in suburbia, factories, the bedroom, and the classroom had implications for success or failure in the face of what was either just an alternative ideology or, as United States President Ronald Reagan provocatively called it, the “evil empire.”

Learning Objectives

- Describe the idea and experience of the Cold War and how it affected Canada and its regions.

- Identify the main features of Newfoundland’s economy and society and the factors that led to its joining Confederation in 1949.

- Assess the ways in which Canada’s international role changed from 1939 to 1990.

- Account for changes in Canada’s political culture, including the rise of human rights.

- Consider the changes in Canada’s relationship with the United States.

- Outline the forces behind the Grand Noirceur and the Quiet Revolution.

- Account for the popularity and the level of success achieved by Quebec’s separatist movements.

- Describe the proposed constitutional changes of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s and the extent to which they succeeded and failed.

- Expand on the social and economic changes in Canada’s cities and in the countryside after 1945.

- Discuss the cultural changes taking place after 1945 and especially in the 1960s and 1970s.

Media Attributions

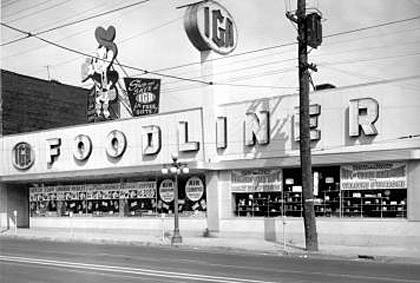

- IGA on Rideau Street, 1950s © Unknown. Source has been removed is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Bomarc B Missile, Canada Aviation Museum, Ottawa, 2006 © Wikipedia user Bzuk is licensed under a Public Domain license

The prolonged period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, based on ideological conflicts and competition for military, economic, social, and technological superiority, and marked by surveillance and espionage, political assassinations, an arms race, attempts to secure alliances with developing nations, and proxy wars.

The Cold War belief that the sheer number of thermonuclear devices and delivery systems in the hands of the Soviet Union and the United States meant that neither side would survive an assault initiated by the other. By assuring their mutual destruction, they would be deterred from initiating a nuclear war.